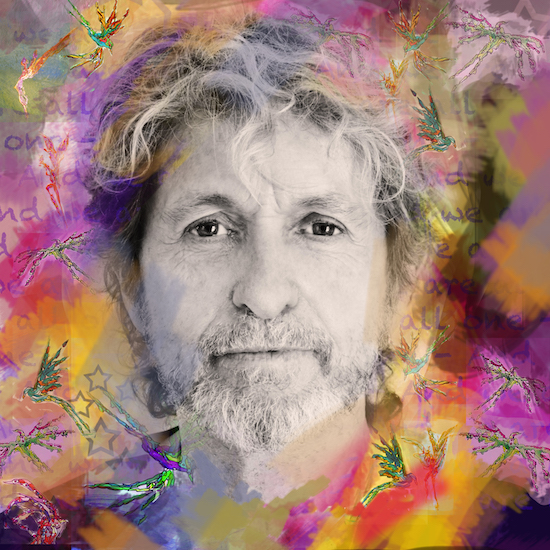

All portraits by Deborah Anderson

By any standards, Jon Anderson’s album 1000 Hands has been a long time in coming. The former Yes singer actually started work on this record 30 years ago with Brian Chatton, a long-time friend from his 60s group The Warriors.

Anderson had contacted Chatton asking him to send a few ideas for a song writing retreat he was planning at Big Bear Mountain ski resort, south of his home in California. “He sent me half a dozen really good ones and I was up there for a week or two and I’d really got it all working very well and then he came up and was in such a funny, wonderful mood, he’s a real comedian,” the singer recalls. “We just laughed for the whole month and I went skiing every morning, it was a wonderful time and the tracks really got some shape to them.”

Thinking two tracks needed bass and drums, he called up Chris Squire, who happened to be in Los Angeles with Yes bandmate Alan White. “For an afternoon they performed on two tracks, that was all,” says Anderson, “but that’s what started me thinking ‘These songs are really good, they’re very current, we just needed in some more talented musicians’. I started calling it Uzlot – meaning ‘us lot’, like you do up north.”

As time passed, Anderson’s plan became more elaborate. “I’d been in touch with Bruce Johnston, I wanted the Beach Boys to sing on it, and I was thinking Wayne Shorter, who I’d loved from Weather Report and Billy Cobham, these kind of characters that I’d bumped into over the years.”

But then, Anderson says, life got in the way. For 28 years the tapes languished in his garage before he was contacted by Orlando-based producer Michael Franklin, saying he had “some capital” to complete the record. So began a process of rounding up guest contributors to fulfil the singer’s original vision.

Anderson says: “I mentioned trying to bring in different musicians and he said, ‘I know Billy Cobham, I know Chick Corea, would you like to call up Jean-Luc Ponty?’ I said, ‘Hey, I worked with him three years ago’. He got Ian Anderson to play on ‘Activate Me’, which surprised me like crazy and I thanked Ian for that. That’s the way life has been for me, I’m very adventurous in my musical world. Over the years I’ve had no fear in working with people.”

Such adventurousness has not always pleased record companies, he points out, remembering how in the 80s he was offered “a lot of money” by Virgin to make a solo album. “Phil Collins was getting going at that time and I think they thought that I could do the same thing.” What Virgin hadn’t reckoned with was Anderson’s desire to make a musical based on the artist Marc Chagall. “I gave them the money back,” he remembers.

Then, when Clive Davis’s label came knocking, he suggested heading to Cuba. “I said, ‘I’m going to sing with the big bands, they’re unbelievable’.” The label promptly stopped the cheque. “They said, ‘No, what we want you to do is work with the producer who’s just done Simply Red’s new album and it was a big hit’.” A compromise was reached, with Anderson agreeing to work with Toto on what became In The City Of Angels. “I wrote two songs with Lamont Dozier, I thought I was on my way to becoming a super-duper star. It wasn’t meant to be.”

The Uzlot project proved more enduring, and he’s glad to see it through under the new title 1000 Hands. “I always thought there was something pretty good about these songs,” says the singer, now 75. “By the time we actually finished it last Christmas I thought there was some magic about this album. The songs had lasted so long, and people liked the album, which is good.”

The Accrington-born singer believes the record even adheres to his original vision. “In its complete idea it is exactly what I was thinking at that time [in 1990],” he says. “The lyrics haven’t changed in two thirds of the songs, we’ve been able to add some of the creme de la creme of music on it and every time I put it on I hear different stuff going on.

“I can still enjoy everything about the album because I wasn’t there in the trenches mixing it. I don’t like mixing, but I would do it from afar. It was done with great respect and friendship from Michael Franklin.”

The pair are now contemplating a choral album of four 20-minute pieces with orchestration. “Since the beginning of the virus and we were told to stay home that’s what I’ve been working on,” Anderson says. “I’m asthmatic so I’m not going anywhere, so I’ve spent the last three months doing all this vocalising work on the music.”

California, where he has been resident since the 1990s, is a long way from Anderson’s roots in the Lancashire mill town Accrington. He says he has been thinking about his post-war upbringing there a lot while writing his memoirs. "Somebody asked me what was the first concert I saw and I remembered when I was maybe one-and-a-half I was in a little stroller it was downtown somewhere in a hall and my mum was serving pies and cakes and my dad was onstage entertaining the people, he had a kilt on because he’s Scottish, from Glasgow, and he had a Hitler moustache and he was telling jokes and playing the harmonica, I remember that vividly.”

Anderson joined his first band The Warriors, with his brother Tony, in 1963. He formed the first Yes line-up with bassist Chris Squire, drummer Bill Bruford, guitarist Peter Banks and keyboard player Tony Kaye five years later, basing his vision on Frank Zappa and The Beatles, and gradually incorporating symphonic elements from classical music. "I always loved Elgar from my childhood,” he says. “I listened to a lot of classical music at that time and I think a little lightbulb came up in my head one time and I realised how they structured the music. It was still unbelievable how the music was created by one person. I became a fanatic over the years for Sibelius and Stravinsky, but I wasn’t the only one doing that – Bob Fripp was definitely into some symphonic stuff when you listen to the initiation of King Crimson, there was that kind of energy and different kinds of structure. It was all a musical adventure and it sustained the Yes band up until The Yes Album where we were able to do something completely on our own.”

After Kaye was fired in August 1971 Yes settled into a new line-up that included classically trained keyboardist Rick Wakeman and their music became as elaborate as their album sleeves designed by Roger Dean. On their fifth album, Close To The Edge, the title song filled an entire side of vinyl.

Their 1973 prog rock landmark Tales From Topographic Oceans was a double album inspired by the Indian monk Paramahansa Yogananda as well as works by the painter and mystic Vera Stanley Alder and Herman Hesse. He was introduced to Yogananda’s work by the painter and metal-bashing percussionist Jamie Muir, who was then in King Crimson. "I asked him how he got to where he is and he explained this book. I went on the Close To The Edge tour around the world reading it. I was getting very deep into the idea that we’re all connected. There’s this Christ consciousness idea that Vera Stanley Alder talked about, we’re all Christ’s consciousness – Jesus was a Christ, Buddha was a Christ, Krishna was a Christ, Muhammad was a Christ, these are the four major teachers in the history of human experience and I got into that, and I still believe that.

"I think a lot of people misunderstand religion in a sense that you can’t say ‘our religion is best’, it’s impossible, it’s kind of sad, it doesn’t work."

As Yes began to fragment in the mid-1970s, Anderson forged a productive partnership with synthesiser pioneer Vangelis Papathanassíou, that was to lead to four Jon and Vangelis albums. Anderson chuckles at the memory of his first meeting with the Greek musician who’d formerly been a member of the prog band Aphrodite’s Child with Demis Roussos.

"I had a friend in London who came by my house one day, I think we’d just finished the tour for Topographic and I was exhausted. He came by with two albums – one was Creation du Monde by Vangelis and the other album was by a Turkish electronic musician called İlhan Mimaroğlu who lived in New York. These two albums really made me jump, it was quite extraordinary work, one person creating all that Vangelis did on that album, it was a complete symphony of energy, and the same with Mimaroğlu. A totally different idea about music, very electronic and very frightening at times, schizoid music, extraordinary music.

"So I got a phone number for Vangelis, he was living in Paris and I went there and called him up. He said (affects a gruff Greek accent) ‘Hello’, I said, ‘My name’s Jon Anderson’. He said ‘What?’ I said, ‘I’m in a band called Yes’, he said, ‘Are you a singer? Well, come over’, so I went over. There was this big guy with a long kaftan on and a bow and arrow around his shoulder. I got into his palatial apartment near the Champs Elysee and there’s quite a long hallway down to his living room, and there’s a little old man there sitting by the TV. Vangelis takes out his bow and sends this arrow down the hallway and it goes right through the window, because the window was open. I said, ‘Vangelis, you could have killed somebody’, he said, ‘Oh, don’t worry, I’m Greek’. I said, ‘I know you’re Greek, but come on’."

Unconcerned, Vangelis cooked a meal while the pair started talking. "I fell in love with the guy, I just couldn’t believe him," Anderson says. "He got on the piano while the food was cooking and started playing Rachmaninov or something like that, that guy could play anything.

"At that time Rick had said he was leaving Yes and I thought ‘This could answer the prayer that I was thinking, a musician that’s very free-form, he could elevate the band into more Mahavishnu (Orchestra) style’, that’s where my brain was at that time. It didn’t transpire. We brought Vangelis to London to join the band and though we tried for two weeks it didn’t work. But Vangelis stayed and got a studio near Marble Arch and I’d go and watch him work.

"Then one day I just sang a song with him for his album Heaven And Hell. We just did it in the space of half an hour. He played, I sang it and then I said, ‘That was a great take, let me figure out what I was singing’ and I went to write some lyrics. When I came back the production was done, and I said it was so beautiful. He said, ‘Well, John, I’m above music, I’m the king’ and I believed him’."

Although it’s 11 years since Anderson last worked with Yes, after they replaced him first with Benoit David and then Glass Hammer singer Jon Davison, he remains keen on a reunion to mark their five decades.

"It was talked about three years ago, why don’t we get Yes back together, it’s the 50th anniversary of the band and I said, ‘I don’t see it, there would be about 15 people onstage, it’s too much’," he says.

"But I had a dream the other week. I was backstage and I realised that’s what happens: I’ll start the show with my guitar and I’ll sing a couple of songs and then Steve’s band will play, then I’ll sing a couple more songs and Rick and Trevor (Rabin) and myself will come on and do something and then all of a sudden we’ll all get together and do ‘Close To The Edge’ and ‘Awaken’ and Bob’s your uncle.

"My mantra has always been it’ll happen when it happens," he says.

1000 Hands is out digitally on Blue Elan now with CD and vinyl to follow on 14 August