“Back in the 1980s Prefab Sprout put out an album called Steve McQueen“, says Mike Scott, the founder and sole permanent member of The Waterboys, “and I remember being disappointed that it wasn’t an album of songs about Steve McQueen, the great actor. It was just an album title. I think that slight sense of disappointment must have stayed with me.”

Forty years later, Scott is releasing Life, Death And Dennis Hopper, a biography of the late counterculture actor in the form of a 25-song-strong double concept album. To give an indication of the album’s ambition, it is being released on the legendary Sun Records label and includes contributions from Steve Earle, Fiona Apple and Bruce Springsteen. Life, Death And Dennis Hopper is everything he hoped the Prefab Sprout album would be and more. It is clearly not a typical release in the playlist-focused streaming age.

Scott’s interest in Hopper dates back to a visit to London in 2014. “I was in the West End and passed the Royal Academy at the bottom of Savile Row, across from [the location of] The Beatles rooftop gig, and I noticed a poster for something called The Lost Album by Dennis Hopper. I couldn’t compute what this must be. Here was a name that to me meant an actor, and yet it was at the Royal Academy, and it was called The Lost Album, so was it something to do with music? I had to go in. It turned out to be an exhibition of his photographs.” The ‘Lost Album’ was the name of a collection of Hopper’s photographs from the 1960s that had been lost or mislaid for decades. “Dennis had been present at so many hinge moments of the 1960s, like the Civil Rights marches and the riots on Sunset Strip. I loved his photography, I loved the world that it represented, and I loved his eye as well”, Scott says. “I could learn so much about him from looking at his photographs. It’s funny that that was my way in.”

The photographs illustrate that there was far more to Hopper than that suggested by his tabloid image of a deranged Hollywood drug casualty. He possessed a strange ability to always be present at key moments of cultural change. His first acting role was opposite James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause (1955), a film that marks the beginning of the late twentieth century’s great outpouring of pop culture. That vital, irrepressible explosion of creativity constantly evolved and mutated over the following decades, yet Hopper was always there to witness it. He was an early supporter of Andy Warhol, for example, bringing him to LA for his first Californian exhibition and buying one of his first Campbell Soup Can prints from him for $75. His 1969 road movie Easy Rider, which he directed and starred in, encapsulated the 1960s psychedelic counterculture and kicked off the director-led ‘New Hollywood’ of the 1970s. “He’s in so many of these cultural moments”, Scott says, “he’s like a stoned Forrest Gump.”

In recent years the idea of ‘the counterculture’ had started to seem almost archaic, because a counterculture by definition required a shared mainstream culture to critique and balance. In a splintered digital world where common touchstones were rare and the abundance of contrary voices could be overwhelming, this was notably absent. Yet there are signs that this is now changing, now that tech monopolies and algorithms are flattening culture and are pushing most towards a bland mainstream of AI slop and contextless distraction. With power now captured by far right oligarchs, there is once again a central culture that needs to be countered. It is the right time, then, to make a case for the principals that drove late twentieth century creativity.

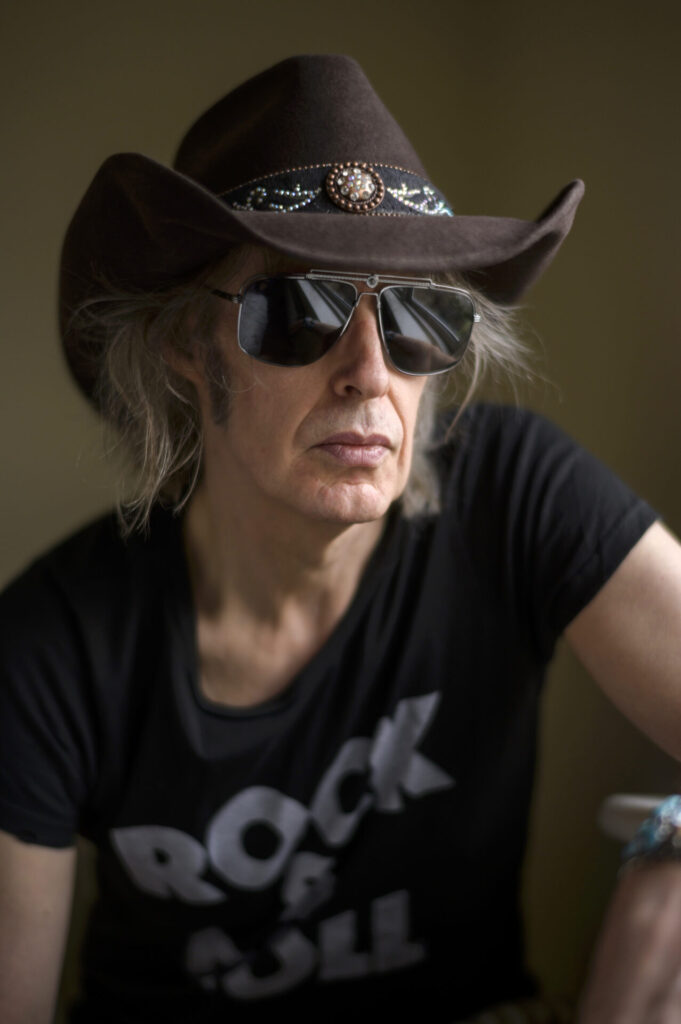

“The counterculture is a name to put on it, but to me it’s just normality”, says Scott. “That explosion of creativity began with jazz music really, but it came into focus with James Dean and Elvis in the 1950s. I was a kid in the 1960s and I was four or five when She Loves You came out. I was nine when Magical Mystery Tour was on TV on Boxing Day. Every Beatles single would be staggeringly different from the last one, and every Bob Dylan album would be an evolution from the last. It was all forward motion. And then in the seventies – not with quite the same revolutionary tempo and perhaps with a little more contrivance – you had people like David Bowie. All that branded me for life. Everything since is trying to recreate that magic. The desire to advance is so important, and that’s what I think music is about. Incremental change or staying the same is pathological to me.”

The story of Dennis Hopper, then, is not just a history of one man. It is a way for Mike Scott to remind us of that pioneering spirit at a time when it can seem absent. “Now we’ve got the backlash”, he says. “The involutionary force personified by people like Trump and Elon Musk is trying to undo all the gains of consciousness and self-awareness and group awareness that developed from the 1950s onwards. They’re trying to undo it, because they want to take us back. They want to put their heads in the sand and take us back to the patriarchal slavery white culture. It won’t work because everything has to progress and move on. The movement forward is the natural way that things should be.”

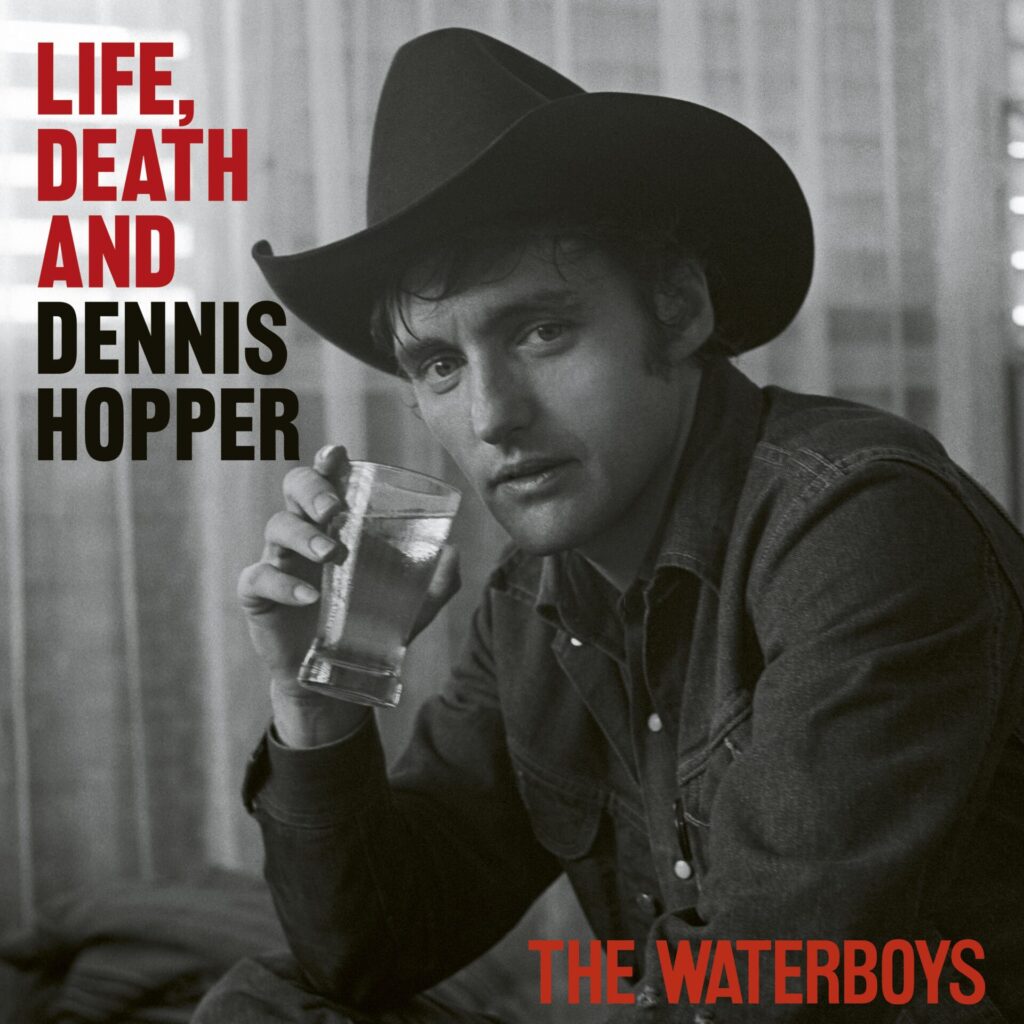

While many people picture Hopper as a wild-eyed jabbering casualty like his character in Apocalypse Now, the album cover photograph shows him healthy, focused and handsome. ‘He has never looked more beautiful than that,’ says Scott. ‘It’s from 1970, when he was making The Last Movie, which was his great folly movie. I found that on one of the photo agencies. I was looking for a cover image and I had a bunch that I’d picked out, but so many of the images were well seen. When I came across it, I realised that I’d never seen it before. I’ve shared it with so many people who know Dennis’s career well, and nobody had ever seen it. It’s like a gift, that photo. It’s as if it was just waiting.’

There are many albums about another artist’s work – The Waterboys’ 2011 concept album An Appointment With Mr Yeats, which set W.B. Yeats’s poetry to music, is just one example – but albums that take a biographical approach to a life are far rarer. Lou Reed and John Cale’s Songs For Drella, an album about Andy Warhol, is close, yet parts of that are focused on Reed’s and Cale’s own personal relationship with the artist. Scott steps back and tackles his subject like an objective biographer – or at least, how a biographer would act if they had an intuitive mastery of the evolutions of American music from the 1950s onwards, able to hop between genres such as country, swing, soul or psychedelia as their story demands.

A biography told through a song cycle, it turns out, can be as informative as a biography built from dense prose. What it lacks in the accumulation of detail it makes up for in energy, emotion and character. The hellish abstract instrumental Rock Bottom – built from fire and breaking glass samples, and a repeated distant insistent voice calling Hopper’s name but failing to reach him – captures his period of dependency and addiction in a way that no book could. Likewise, the conflicting emotions of anger, love and resignation in Fiona Apple’s vocal for Letter From An Unknown Girlfriend tells you everything you need to know about Hopper’s abusive nature. The overall tone of the album is celebratory, but it is not blind.

Whereas biographies and autobiographies are usually constrained to the perspective of their author, these songs are free to take on different voices and offer differing viewpoints. One song even comes from the perspective of one of the characters he played – the monstrous Frank Booth, from David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. The track – ‘Frank (Let’s Fuck)’ – is notable for containing more swearing than the rest of The Waterboys back catalogue combined. Alas, it seems unlikely to be played on the forthcoming tour of the UK and Ireland, which starts in May. “I don’t know if I could pull that off on stage”, Scott admits. “But it was a lot of fun. It was no problem when I was sitting in my studio, but I had to work on it when my daughter wasn’t in the house.”

The inclusion of such well known guests as Apple, Steve Earle and Bruce Springsteen – who contributes a spoken word section to Ten Years Gone – raises an interesting question. The Waterboys have famously had more members than any other band, ahead of even Santana and The Fall. Does this mean that Bruce Springsteen is now officially a Waterboy? “It’s a lovely idea”, Scott says, “but I think you have to play live with us for it to count.”

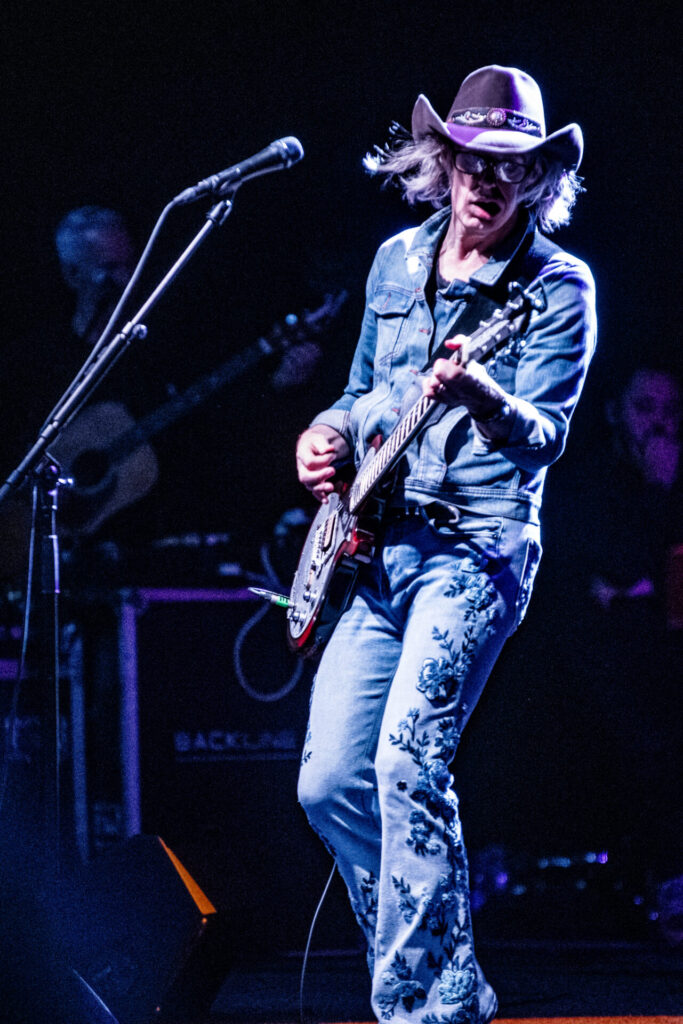

The later years of Hopper’s life, after he had beaten his demons and his addictions, found him healthy and productive. Early 90s movies like Speed and True Romance introduced him to a whole new audience and he regularly appeared in around five films a year from that point on. In a similar way, Scott appears enthused, prolific and energised by having pulled off such an ambitious, original and singular record. This comes at a time when, after over forty years of The Waterboys, no-one would blame him for sitting back, relying on his formidable back catalogue, and settling into a comfortable existence as a heritage artist. At the mention of the idea, he looks horrified. “I’d be bored stiff”, he says. “I don’t mind playing the old songs, but I’ve got to have somewhere new to go as well.”

This is an attitude that explains why he was so drawn to Dennis Hopper. To write a biography is, by definition, to look backwards. But when we look back we see a story of a life that tells us we are here to progress.

Life, Death And Dennis Hopper is released via Sun Records on Friday