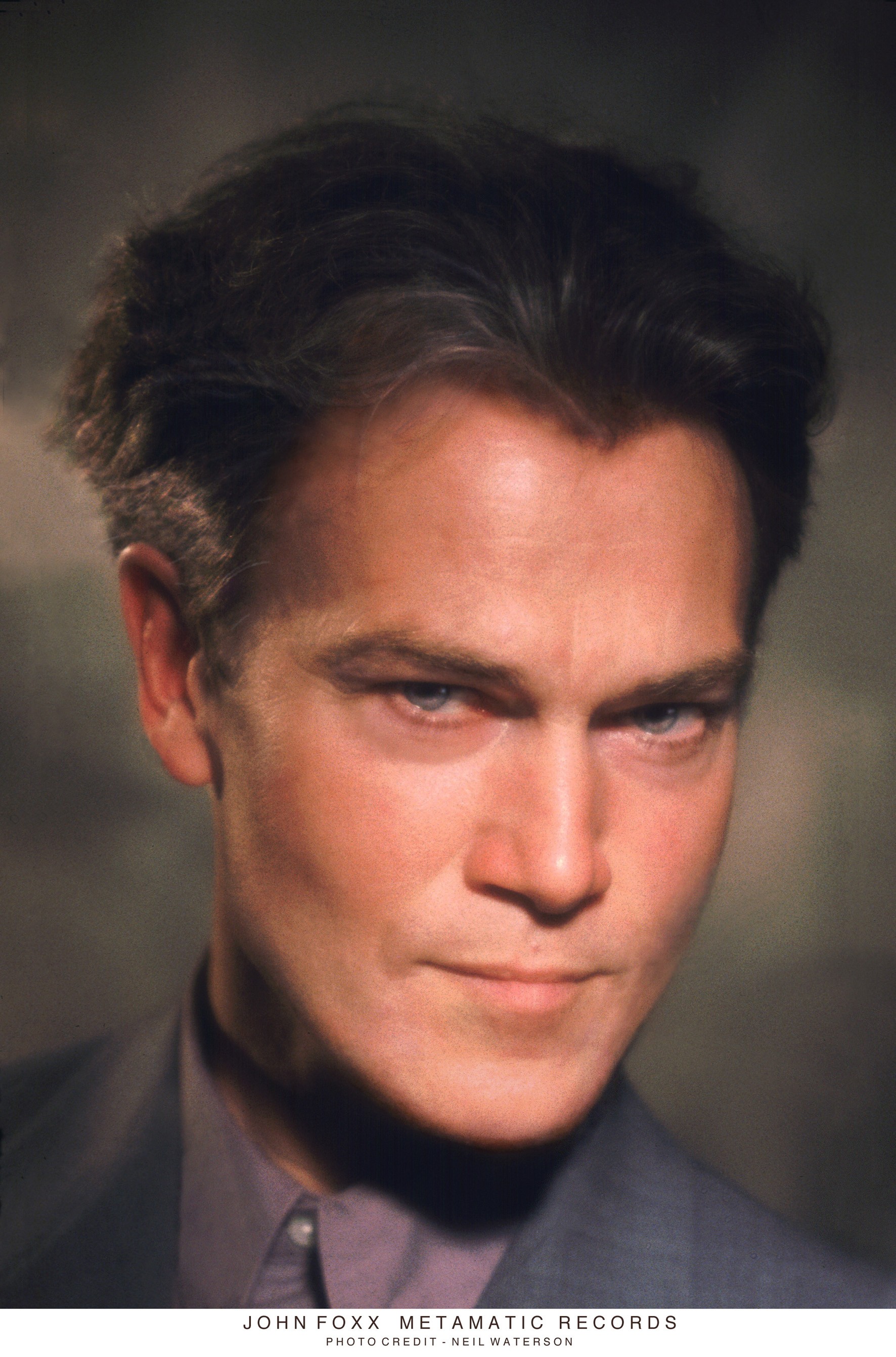

As part of the original Ultravox!, John Foxx helped shape much of the late 70s synth boom. The ‘single biggest inspiration’ to Numan among others, after subversive pop hits in the early 80s with the likes of ‘Underpass’, ‘Burning Car’ and ‘Europe After The Rain’, he took a long career break and has adopted a much lower profile in recent years. But he is once again musically active and, pleasingly, retains the self-deprecating urbane humour of old. September saw the re-release of four career-spanning extended double-disc CDs, including a newly compiled best of, Glimmer.

Mike Stone, who helped start Beggars Banquet, told me once that he recallled Ultravox! going down to their basement rehearsal room in Fulham, trying to get what he called a ‘big board with pegs in it’ through the door. He thought it was a prehistoric synthesizer. How much were those early Ultravox! records conceptual, and how much getting wires and boxes to fit together and seeing what you could produce with them?

Both, really. The point was to find out what these strange new instruments could do that hadn’t been done before – I figured that new instruments had always radically altered music in the past – for instance the electric guitar. Here was the next major shift – the synthesizer. It could make violent extremes of sound, from subsonics to bat calls. At that time we wanted a total experience. It was a sort of sonic terror allied to the most extreme guitar feedback possible plus a battery of megawatt strobe lights. No-one walked away unchanged from those mid-period concerts. On the other hand, we were equally into romantic lyrical beauty. The synths could do both.

A lot of people cite ‘Young Savage’ as one of the greatest punk songs of all time. I tend to agree. Did you feel any affinity to that movement?

I felt total affinity with Punk, but I was disappointed that it got so conservative so quickly – it really strangled itself. An old man before it was a youth. Born 1975 died 1977. Never realised its potential.

Everyone knows that the Midge Ure version of Ultravox went on to record ‘Vienna’ etc, but you almost joined an even more famous band, The Clash, in their London SS guise. Could you tell us about that?

Well, I went out one night for a drink with Mick Jones and Glen Matlock. (I always liked those two – they were truly central to that movement and very sharp. They just radiated). Mick told me they’d considered asking me to join their new band pre-Clash. They’d seen us at the Marquee and in Islington, but hadn’t approached me, because Mick felt we were already off the ground as a band. Actually we were only supporting at the time. The irony was, I’d seen Mick at the Patti Smith Roundhouse gig in 1974 or 5, and thought he looked right and considered asking him to play guitar. He looked like a young Keith Richards. Then I thought that anyone who looked so good probably couldn’t play guitar anyway.

Daniel Miller at Mute Records often talks about the inevitability that younger musicians would start to buy synths rather than guitars as soon as the technology became affordable in the late 70s. Is that how you saw it?

Yes, Dan is quite right. All the bands wanted sonic mayhem by all and any means. Synths supplied that in a new way.

Were you similarly disenchanted with ‘trad rock’ formats?

There was no underground at all at that time. London was dead. All the existing formats seemed exhausted. We were all floating around London forming and reforming bands and trying new things out. Then The New York Dolls arrived and galvanised the entire scene. Real glam trash. Beautiful. They proved it was possible to be trashy and good at the same time. Kicked everyone into action at a desperate moment. They saved us all. At that moment, I was drawing lines into New York and the Velvets, European avant garde and electronic music, previous generation’s Brit Psychedelia plus a ragged sort of insulting glam. I guess this was the start of the New Wave. By the way, whoever coined that New Wave byline is my hero. Because a New Wave is precisely what it was – and precisely what was needed at that moment.

Was it the case that your songwriting ‘needed’ the development of synthesizer technology, or that you could have adapted it in a previous musical generation?

I think I could have written and recorded in any period, but of course there’s no way to be sure. I started off singing and playing a 12-string guitar in the Bolton Octagon in 1973, then in a room over a Salford Pub, supporting a Manchester band called Stackwaddy. At first the room was empty. Eventually it became full. But there was nothing happening in Manchester then, No scene at all, so I had to leave for London and got the band started. The idea was to be London’s Velvets. We even had a base in a factory at King’s Cross. The members of what were going to be The Human League came down there, totally by accident. The synths allowed more possibilities. I was becoming really interested in what could be made in a recording studio that couldn’t be rehearsed or developed in any other way. After [hearing] ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ I realised that the studio was really the most important instrument of the future. That’s why we got Eno to work with us. It was either him or Lee Perry.

Ultravox! were clearly a big influence on Gary Numan, but also OMD, the Human League and others. Do you think that was largely a consequence of the aforementioned availability of technology, or do you hear echoes of a more direct influence in their work?

Both, I think. We were the first to get out there, so everyone naturally checked us out.

In terms of the reissues, what were your thoughts on compiling Glimmer? Does it constitute a ‘greatest hits’ as the title implies, or something different? You’ve obviously included some of the revamped versions with [recent collaborator] Louis Gordon rather than what may be more familiar versions. What was the thinking there?

Simply what seems the best at this moment. This changes all the time, of course. The new versions are just another angle, and may be refreshing. We’ll see, after another thirty years.

On The Garden, The Golden Section, In Mysterious Ways – the commonly held perception here is that you moved away from the harsher tones of [debut solo album] Metamatic and increasingly incorporated a pop aesthetic – was that you simply growing as an artist and wanting to explore different textures?

Yes – and my own misperceptions about what I’m really about as an artist. Everyone seems to need to drive on the pavement a bit before they get back to the road. Lou Reed has the best term for this syndrome – Growing up in Public – Very hard to do. Inevitable that you get it all wrong sometimes.

Did a part of you ever want to write a ‘perfect pop’ single?

Oh yes. Anyone can be a damn fool. Perfect Pop is the Bermuda Triangle of popular music.

You recorded The Garden while living in Italy? How much did that rub off on the songs?

Changed my life. I discovered where Europe came from.

The Golden Section features more pop-orientated fare alongside electronica. Some have suggested a Roxy Music influence.

More a mangled sort of Brit Psychedelia really. A wee glimpse of Roxy through a burnt out acid lense.

Do you accept the criticism of the cover art?

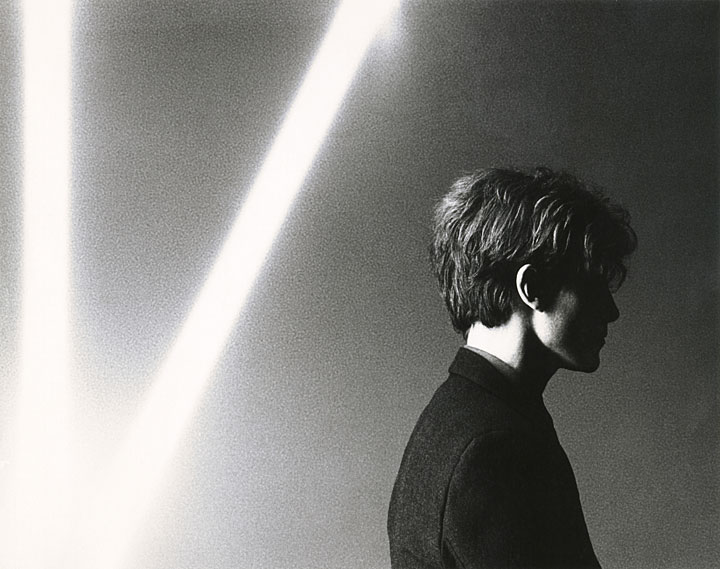

Oh yes. But I still maintain that Brian Griffin is one of the best photographers in the world. He’s a true artist. I just got in the way of his lense, is all.

In Mysterious Ways didn’t make much of an impact on release in 1985. You once said that the reason you didn’t release your ambient album Cathedral Oceans in 1983 was because Virgin simply didn’t understand it. Does your regret at not being able to release the latter shadow your thoughts on the former?

No – I think they’re totally different projects. Cathedral Oceans is much more personal.

Do you think things have changed for the better in the way that music is no longer so strictly stratified and marketed as it once was?

Absolutely. There was only Pop, Classical and Jazz then. If you weren’t in those boxes you were fucked. Things have opened up beautifully since then. Full spectrum.

On a similar theme, do you believe you were strait-jacketed in terms of public perception by your earlier work, both solo and with Ultravox!?

Of course.

How is that a very forward looking artist like yourself has ‘fallen through the cracks’, to an extent.

I don’t think there are any cracks to fall through – either people like you or they don’t.

Lack of careerist ambition?

To some extent. I’m actually wildly ambitious, but reconciled to the fact that my ambitions don’t fit with many people’s expectations.

Interests in things outside the silly pop merry-go-round?

I don’t think pop is silly. I think it’s an accurate snapshot of certain current concerns and desires. If you want to be even a peripheral part of it (as seems to be my role) you have to select carefully where you attempt to interject yourself, if at all. Mostly not at all. That’s not humble – its absolutely realistic.

You disappeared from public view for around a decade and reverted to your own name. Why was that? I accept, incidentally, that you actually convened some very interesting artistic projects during this time, albeit non-musical.

I hated the sterile music of the period. I burnt out against it. Didn’t like or trust my own decisions. Happens to all of us at some point. At time I was also mildly insane and inclined to wander. Little has changed. I’m eternally grateful to have been able to blunder into a form that supplies me with some income, while I carry out obscure personal investigations. What more could anyone ever want?

We’ve touched on the influence you had on other artists employing synthsizers, but beyond that, you could draw a line between what you did and some of the Britpop generation – especially Blur and Suede.

There’s a direct line from the Velvets through Roxy to the first Uvox to Blur to Radiohead and beyond. Others are setting out as we speak. They all refer to the same genetic base. They all boil in the same nebulae – it’s the fundamental, wonderful, glowing genetic line of music and adventure versus merely flogging stuff…

And I know that the Klaxons have been deifying you in the press of late. Presumably that’s all very nice, especially when your influence shows up in more unexpected areas?

The Klaxons have a rare generosity – the mark of minds who value ideas more than a cheap seizure of territory. Proof that there’s hope yet.

Is collaboration, as you have done recently with both Louis Gordon and Harold Budd, now your preferred way of working?

Oh yes, Collaboration is fun.

Does it offer you something of a safety net to not be purely a solo artist these days?

No such thing as a safety net. It simply offers additional avenues for potential swift extinction, but in very good company.

You’ve said that one of your primary inspirations is London, but also nature. Could you elaborate on the way that fits together?

London is the centre of The Quiet Man‘s universe. Also of mine. It has a new emergent form of nature – Grey Nature – this is Nature unconfined by the world outside cities. We will begin to see the emergence of startling and subtle forms of highly specialised life forms from now on. Alligators in the sewers are just a daft beginning. The next generation are swift and subtle and almost undetectable. They live on momentary intersections and coincidence, and have learnt to take sufficient advantage of these to predicate entire new ecologies. The tabloids will have a field day. So will any agile biologists. Just watch. The next generation of Attenboroughs will investigate The Cities – The Grey Planet Series.

What do you make of the changes in London through the years, especially having spent time living abroad?

Relish the changes. Got me stab-proof vest with electro-death reply mode switched on all the time.

Could you tell us about your other future plans?

Plans to present London as an Overgrown City – projected onto Battersea Power Station. Simultaneously we will adopt a street in central London to free from cars, and plant vertical gardens into. This is the first emergence of The London Forestry Commission. It is a plan to unite all the parks and squares in London – from Hampstead and Richmond to Hyde Park via Soho Square to the River. The aim is to make London into the kind of place we’d all like to live in. Instead of the dreadful car-dominated pedestrian-cowered rut it is at present. Bring your sandwiches.