Often retaining a fated air that can’t really be expounded years later, chance childhood encounters with film can register with the oddest sense of import. Whilst my giddy lapping up of the likes of Jurassic Park and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial as a child is now very comfortably shrouded in the murkiest recesses of time, catching a first glimpse of what I was convinced was the bogeyman, a cross-legged ten-year-old channel-hopping one late Halloween night in the late 90s, remains very much burnt on the proverbial retina.

Shot over 20 days in the spring of 1978 in South Pasadena, California, I would later learn that John Carpenter’s Halloween all but transformed the landscape of modern horror in the space of 91 impossibly unnerving minutes, simultaneously re-framing the director as a genre-defining auteur wielding stasis and sustained tension like a scythe. But what indisputably lent Carpenter’s work its cult cinematic mastery is the unique atmospheric signature conjured by his self-composed, home-recorded soundtracks. From The Fog, Escape From New York, and The Thing to Big Trouble In Little China, They Live, Assault On Precinct 13 and countless other besides, the enduring élan of his work resides firmly within the synthesis of his intrepid audio-visual vision.

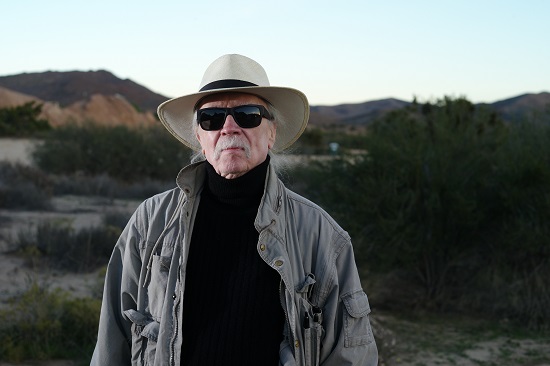

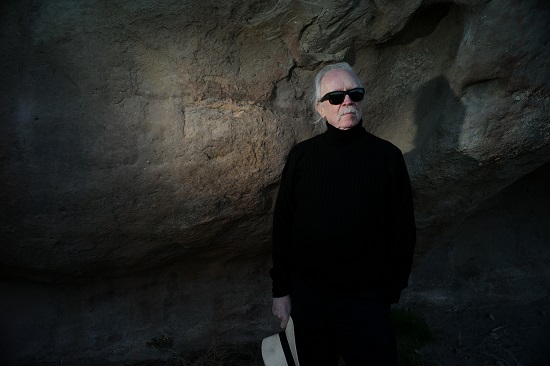

Nowadays, it’s not conjecture to say there are few artistic statements that 68-year-old John Carpenter is yet to make or make his very own. With his stellar, second non-soundtrack album, Lost Themes II, set for release in April, he will finally perform his first ever live shows this summer at Primavera, ATP Iceland and New York ahead of English dates later in the year. As well as offering exclusive first details about finally playing his legendary scores on stage, Carpenter talks to us about never watching his old movies, embracing the digital age, the modern spirit of horror, getting paid and the freedom of making music with family, where the very pure driving force is a love of the craft as well a wonderfully grounded awareness of the need to act upon unfinished business when one still can.

The live shows are a massive part of what’s happening for you this year. As to be expected, a lot of people are very excited indeed. Why now and how did it all finally come about?

John Carpenter: It was an interesting thing. I’ve made these albums – two of them now – with my son, Cody, and my godson, Daniel. At some point along the line we began talking, "Why don’t we do a little tour? We don’t have to do a long tour. We’ll do a little tour." I stewed about it and thought, "Well, wait a minute – how great would it be to play with the two of them? It would just be unbelievable." So that’s what got me to do it. That finally got me to say, "Ok. I can do this."

You’ve said your soundtrack work – which is often extraordinarily subtle – almost needs to be ‘invisible’ for it to be used effectively. For the first time, you’re going to be visible. It’s going to be a ‘physical’ experience. Are there nerves there?

JC: Oh, sure. But it’s going to be a full band. It’s not just three of us either – there’s five of us. We just rehearsed yesterday, actually. We’ve been rehearsing quite a bit. We want it to sound really good. And since I’m a director there will definitely be visual elements included. In some cases you’ll see the movies that I scored whilst I’m playing the themes. Then we’ll play themes from the two albums and that’ll be something different, too. So it’s going to be a retrospective of my music but also new compositions being played. I know it’s going to be fun but it’s also going to be challenging.

Do you feel much of a weight of expectation there? Would you care if you got a few negative reviews where the consensus was ‘It didn’t come off’? Would you give a shit, essentially?

JC: Yeah, but I don’t want to necessarily dwell on that. Sure, I care that people like it. I don’t not give a shit, you know? If people don’t like it, fuck ‘em [LAUGHS]. I’m an old man now. Be nice to me!

I’ve been enjoying Lost Themes II, which is released in April. A big difference between it and the first record is that you were all in the same room together writing and recording the music together. Did that help?

JC: Yeah, I’d say that was a big difference. The last time Cody was in Japan and Daniel and I were here, so we did things long-distance. This time we’re all three there and we’re all three playing. It’s just great fun. Man, we just had a blast. I mean, this is more fun that making movies. It’s definitely more fun.

Does it feel as rewarding?

JC: Man, that’s a hard question. I’ll always be deeply, deeply in love with movies. It was my first love but I do not love the amount of stress and the amount of aggression it takes to make a movie. It just kills you. Music is just such a relief. And for somebody at my age being able to do it is just great.

When you were younger and studying film at USC back in the Sixties, what lead you step away from that more guitar-based material in early soundtrack work like The Resurrection Of Billy Bronco? Was it in your discovery of the synth and thinking it would simply work more effectively?

JC: Well, the synth provided something that any low-budget filmmaker – or student filmmaker – knows, which is that you can sound really big and dynamic with a synthesizer because you don’t have the money to hire an orchestra. That’s expensive – never mind having to rent a place to record the orchestra. Orchestras are still intimidating to me. But with synthesizers I can double-track and triple-track ad infinitum. I can sound big like an orchestra – that’s why I started used it. It’s a keyboard instrument where you can play the equivalent of strings on it. I just thought, "This is great."

I’m pretty confident my first vivid introduction of the synthesizer was in your soundtrack to Halloween, which remains my favourite film to this day. How much thought and time did you put into getting those sounds out of the instrument? Did you deliberate over it much?

JC: I don’t deliberate. It’s an interesting thing; it just comes out of having seen a lot of movies, having grown up with music and all those things. It’s not a thought-out process and never has been. It’s always a ‘feel’ process, which makes it delightful. That’s my approach and it’s worked ok so I think I’m going to stick with it.

You use Logic Pro to create music nowadays, the likes of which many consider a lot easier than the old analog setups of yore. Have you totally embraced the digital realm at this point?

JC: Yes, I have. I love it. It’s really terrific. I think it’s essentially the future of music. It’s just served me so well. I keep wondering, ‘Why the hell did I rebel against this?’ I come from a different era. That era was magnetic tape. It was a whole different feel. There was a lot of purists about. They don’t like digital sound but I think it’s great.

It’s been said Lost Themes II is a more ‘focused’ effort compared to Lost Themes, which may be lot to do with a tight schedule. Do you think that was the case?

JC: Sure it did, absolutely. We would usually just sit down and sometimes Cody or Daniel would bring in a sketch. Or I would bring in an idea by myself and we would just play something to see if we could make something out of it. It’s isn’t writing as much as it is sitting and playing and letting the music come out of you. It’s total improvisation. All of it. All of it comes out. It comes out in interesting ways and this is what the fun is.

When listening to the Lost Themes II a steady stream of images and would-be scenes pop into my head, which I find quite intriguing. But were there any visual ideas running through yours when writing?

JC: There are definitely visual ideas running through my head. Music brings up all kinds of notions and images. That’s what it’s designed to do. It’s designed to score the movies in your head. That’s what I want. I want to bring out some visuals for you. But it’s also a motivator – I want you to use your imagination to create your own movies. Let me be your soundtrack.

I like how it’s effectively inverting how, for the most part, you score your movies whilst sitting down and watching the first cut. This time it’s almost the opposite.

JC: Absolutely. And that’s the whole point. Everything else is just secondary to that. It’s just freedom. Sometimes we say in America, ‘Nobody has a second act.’ Well, have fun, man. I’m an old guy and here I am doing this. It’s great.

Of course, with touring comes travelling. Do you enjoy it and have you been to Iceland or Barcelona before?

JC: Hell no. That’s the part I’m not really excited about because I’m not a great traveller. I don’t want to sit in an airplane and we’re travelling a lot. We’re going to go to Spain, we’ll come back and we’ll go to Iceland. Then we’ll go to Switzerland and then come back. And then we’re going to go to England to run about. We’re really looking forward to playing. The actual flying about, not so much.

I noticed a parallel with how you’re making music with your family and how many of your films featured various people who made up a kind of family. From production staff to Kurt Russell, Donald Pleasance and innumerable others.

JC: I hadn’t thought of that but that’s very true. Besides, my son’s a better keyboard player than I am and my godson plays the lead guitar, so they come in handy.

Going back to the very beginning, which films and soundtracks do you think really stood and compelled you as a youth?

JC: The big profound one was when I saw Forbidden Planet in 1956. I was 8 years old. It had an all-synthesized soundtrack by Bebe and Louis Barron. It was unbelievable. It’s still unbelievable. They did it in a really crude way with loops and all sorts of ancient technology but man, the sound. I’d never heard anything like that. It blew my mind and carried me on. I remember various soundtracks. One in 1977, the Tangerine Dream soundtrack for Sorcerer and of course, The Exorcist and things like that.

Music has played a very sizeable role in the effect, influence and legacy many of your films, from Assault On Precinct 13 and Halloween to The Fog, The Thing, They Live and beyond. Were you always aware of how it’s used or indeed not used can make or break a film?

JC: Sure. You know the helicopter attack sequence on the Vietnamese village in Apocalypse Now!? ‘The Ride of the Valkyries’ is playing and its really great. But what I used to do was play it and put a different piece of music underneath. It would completely transform it. Sometimes I’d play ‘It’s All Over Now’ by the Rolling Stones and it really worked. So it’s always a real big choice and not to have any music – to have something not pulled along by music, sound effects, natural sound or dialogue – is just as important sometimes. The silence can be an instrument in itself and sometimes more frightening.

I’m not sure if you watch your old movies…

JC: God no. I never wanna see ‘em again. Don’t make me! [LAUGHS]

Well, thinking about those films do you recall any particular modus operandi that just worked when scoring?

JC: The soundtracks in the movies are all functional. Basically what the music there for is to enhance the image, enhance the drama or suspense– whatever it is you’re trying to do. It all comes out of necessity and function. So I sit down after the movie is cut and go, ‘What do we need here?’ And I would just compose in the same that we’ve composed these albums: just improvise it. But the new music is completely different because it’s not functional. Just out it comes.

For me it’s the sound of freedom and fun.

JC: I love what you just said. That’s it. It’s freedom. I’m going to use that. Can I use that please?

Work away. Touching briefly on the last decade or so of horror movies, do you think the actual genre has carried on the proverbial torch of passion and flair of the early days?

JC: Sure. Horror is such a durable genre. It’s going to last forever. It was there at the beginning at the birth of cinema and it’s going strong now. And it keeps getting re-invented. That’s what I love about horror. Every generation re-invents it.

Do you think it’s re-invented it with the same creative spirit?

JC: Well, horror movies are pretty much generally the same. Most of them are bad. Very few of them are average. And very few are good. And it’s always been that way. But I haven’t seen a whole lot of them recently. I need to catch up. The last really, really good horror film that I watched and loved was Let The Right One In. The Swedish version, not the American version. I thought that reinvented the vampire genre. I really dug it.

Not exactly an elephant in the room but what are your thoughts on the Escape From New York and Big Trouble in Little China remakes?

JC: I’m happy if they pay me.

How much?

JC: As much as I can get!

Right answer. Do you realize that you essentially invented grunge music by the way you dressed Alice Cooper in Prince of Darkness?

JC: I’ve no idea what you’re talking about [LAUGHS]

You should definitely make an exception and re-watch that one to see. Another quick one: what’s the scariest chord?

JC: There are no scary chords – music is only frightening in context. It’s not frightening sitting out on its own

I’d be inclined to agree there. Thanks, John. Enjoy what the next months hold.

JC: Thank you, sir. We’ll go out on the road, make some music, have a great time and make a few bucks and enjoy life. Life is here to be enjoyed.

Lost Themes II is out via Sacred Bones on April 15. Details of all forthcoming John Carpenter tour dates, including Simple Things festival in Bristol on October 23, here