What will life be like in 1000 years? Will humans still exist? Will there be a recognisable London? Such are the idle thoughts that flow to mind as I stand on Trinity Buoy Wharf, downriver from the City, upriver from the Thames Barrier. It’s hard to visualise how much can and will change in such a span of time. 1000 years ago, this harbour landscape was primarily marshland, with what locals there were fixated on the threat of Viking attacks, portentous comets, Messianic returns and the end of days. If anything, time is accelerating with every passing year. From across the Thames, the O2 Arena looks apocalyptic and Ballardian, a bleached turtle’s shell, like the Runit Dome filled with irradiated waste on Enewetak Atoll.

Climbing the spiral staircase of London’s only lighthouse, built between in 1864 and 1866, I discover that the Longplayer project, dreamt up by Jem Finer, is not apocalyptic at all but an act of faith that the future would happen, a reaching out beyond the finite human lifespan to somewhere and someone we can scarcely conceive of. Originally commissioned by Artangel, Longplayer is “a 1000 year musical composition [that] began playing at midnight on the 31 of December 1999, and will continue to play without repetition until the last moment of 2999.” The music, ringing chimes and hum from singing bowls, swirls around an attic space. You don’t even have to be there to hear it – Longplayer is streaming online here. This melody will last for centuries after we are all forgotten bones, and encountering it is reflective and dreamlike. It’s not morbid at all to contemplate this time that stretches out beyond us, but instead gives a true sense of wonder.

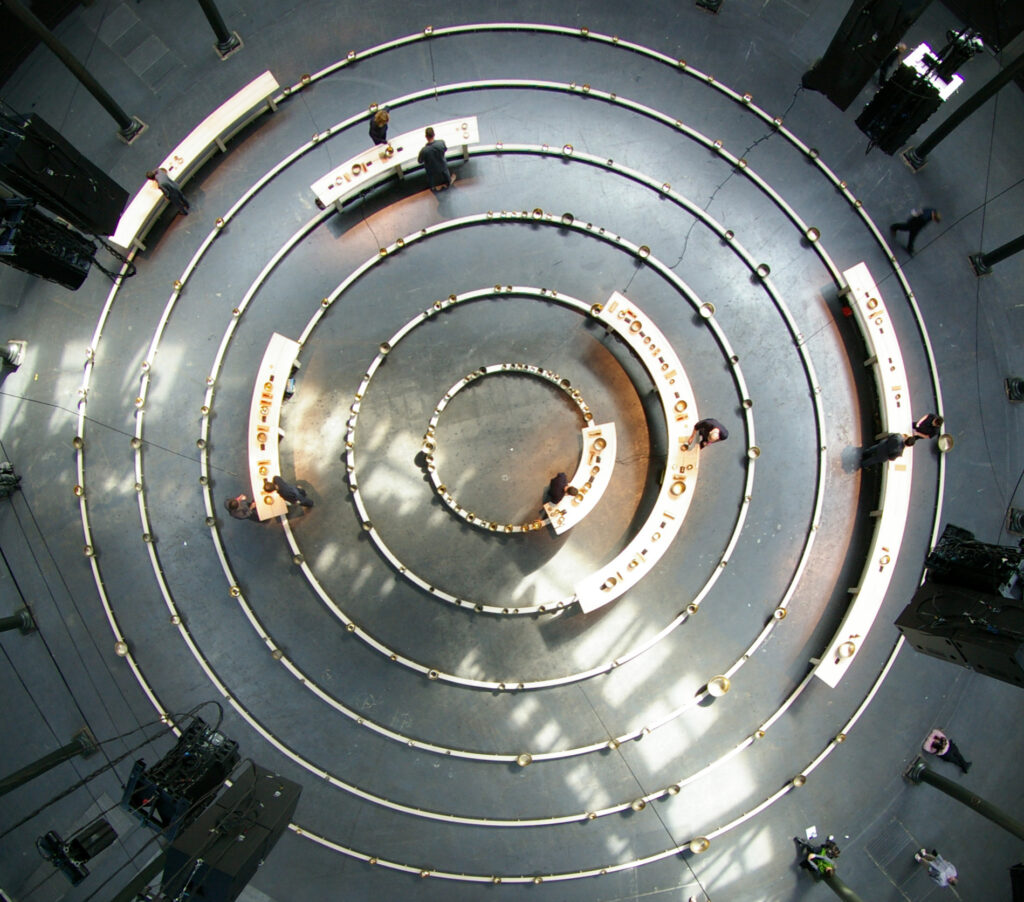

On 5 April, Longplayer will head north west through London for Longplayer Live at the Roundhouse in Camden. The performance will consist of a 1000-minute section of the piece performed collectively by artists including Spider Stacey, Gina Birch, Benedict Drew, Jim Sclavunos of the Bad Seeds, Susan Stenger, James Bulley, Lori Goldsten, Andrew Kötting alongside 18 young people from the local community, on Finer’s “vast, Bronze Age synthesiser”, and will last until midnight. Events will also include Caleb Femi’s Longplayer: Long Poem, described as “an immersive 100-minute poetry event exploring time, inheritance, survival, and the unknown.”

I met up with Jem Finer in a pub in Kentish Town. By chance, it was one he’d played in with The Pogues years earlier, and he pointed out where the stage and audience used to be in a now-gentrified space. I had mistakenly assumed there were two distinctly separate sides to Finer’s work, the meditative Longplayer seeming antithetical to the raucous Pogues. Yet few bands could touch The Pogues in terms of sensitivity (‘A Rainy Night in Soho’, ‘Thousands Are Sailing’, ‘The Old Main Drag’, even ‘Fairytale…’) or erudition, writing songs inspired by everything from the poetry of Federico García Lorca to the fever dreams of Cú Chulainn to Jean Genet’s Our Lady Of The Flowers. Finer has an infectious curiosity for knowledge, and its sharing. We talk of hurdy-gurdies and soundwaves, his work with Jimmy Cauty (Local Psycho and the Hurdy Gurdy Orchestra) and Alasdair Roberts (Two Brothers), with whom he shares a mutual interest in centuries old ballads. Then there’s his affinity to those, such as James Holden, who are at the forefront of organic electronics. Even before we speak of music, scenes from Cormac McCarthy’s books and half-remembered lines from Ulysses (“The heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit”) casually bubble up in the conversation.

Equally, Longplayer feels like a sanctuary because this new millennium has already proved to be a turbulent one, a grim parade of crises that shows no sign of abating. A photographer I know once visited Cormac McCarthy’s ranch and found it full of books not primarily on literature but science. It wasn’t the misty-eyed wonder of popular science evangelists, but rather an awareness of how strange and tenuous our species’ continued existence is. You can see it in the writing: a catastrophic scorched layer of earth. Longplayer seems zen because it exists surrounded by a world inclined to chaos and destruction. Once you start contemplating the enormity of “stars and stuff”, as Finer puts it, you can just as easily unlock a kind of terror as well as wonder. The same goes for contemplating the passing of epochs and their vastness, and the human capacity for self-annihilation.

Before I can ask him about the crippling existential vertigo of existence, Finer mercifully reins us back in, “From being a kid, I wanted to make a thought experiment, to make a long continuum of time.” And sure enough, Longplayer feels like escaping as much into thought and feeling, as out of them. I wondered what drew him to the science and technology side of the project. “Nothing I have done has ever really been planned,” he says. “One thing has led to another. I was rubbish at school. I didn’t like it. I was quite good at maths though and I was always pushed towards physics. Those things have stood me in good stead. Maths is in everything, including music. If you unlock that, you have access to so much. The physics of sound. How different frequencies become harmonic.”

Until our talk, I hadn’t realised Longplayer and The Pogues were both deeply concerned with the passage of time, the former being more obvious than the latter. It becomes apparent when speaking about the triumphant gigs The Pogues have played in the likes of the Hackney Empire with a host of their bastard children (in the best possible sense) – elements of Lankum, Goat Girl, Fontaines D.C., The New Eves, The Deadlians and so on.

“Hackney Empire blew my mind, I have to say. That whole thing is totally related to the Longplayer in this weird way of life, and how you follow life, as time goes by, it all starts to make sense and fit together. It was like The Dubliners. They were a huge influence on the beginnings of The Pogues and we ended up playing with them. There’s this tradition passing through The Dubliners into us and onto these others now. That gig had a really strong visceral feeling. We’d completed a circle. We’d taken something in, digested it, reinvented it in a sense, and passed it on.”

This process gives a lie to the prevailing idea that looking back or carrying forms on from the past is somehow innately conservative. Instead, they are proof of the quote, attributed to Gustav Mahler, that “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.” Keeping a culture alive means continually revitalising it rather than mummifying it, even if that means taking flak from traditionalists and cultural embalmers. Formed in the crucible of punk, this was The Pogues mission statement from day one, according to Finer.

“When I first heard Shane [MacGowan] talk about John Montague and traditional Irish songs, I was like, ‘Fucking hell, this is a brilliant idea.’ He asked me to come play guitar and I thought, ‘I want to be part of this.’ What really excited me was taking something timeless and putting one’s spin on it and sending it somewhere else. With Longplayer, there was this big question as to what sounds were used and if we used sounds that were 1990s sounds, they would have immediately sound dated. And I did the same thing as The Pogues without realising it, I went back to something very old and elementary. The singing bowls as instrumentation. They go back at least a thousand years. They’re a bell essentially. They sit like a bowl instead of hanging. Without realising it, it’s the same kind of trick in a way. You take the timeless and renew it. Compared to folk music, Longplayer is a relative newcomer.”

Another misconception on my part was viewing Longplayer solely as a linear passage, stretching out into the future like the river it overlooks or the nearby Meridian Line. This is only one way to look at it. “The score is adaptable, an abstract,” Finer explains. “You can turn it into computer code or what we are doing at the Roundhouse – transforming the score into a physical performance. It’s quite helpful to visualise…” Finer pulls out his phone to show the notation. Graphical Score : Longplayer Circles orbit circles in what seems a work of visual art in itself, akin to the graphic notation of the likes of Cornelius Cardew and George Crumb. It resembles a map of the solar system. I ask if this was intentional, a kind of music of the spheres idea. “The amazing thing was it wasn’t planned, it sort of fell out of the system,” he says. “This was in it without me knowing it.” Finer connects this revelation to playing with The Pogues: “Very odd things would happen. In fact, the most interesting things are when someone would make a big mistake and other people would be thrown by it, and for a few moments you get this out of kilter thing that goes off on its own tangent, like a train going off the track and bouncing around but finally getting back on it.”

The survivability of Longplayer is at the core of the project. The computers involved will be archaic in 100 years’ time, let alone 1000. These concerns, it turns out, were built into the project, which is as much about renewing as sustaining, “Longplayer is originally written in code,” Finer says, “I suppose if I have a background, it’s in computing programming from the 1970s because that’s what I studied at university before I started creating music. Ever since I got my own computer, I’ve been trying to write code that creates music. You’re not going to sit and write a thousand years of notation, so I did various experiments until I found the system, and I sat down for two years, experimenting with all these forms and programs, but always with the thought it will have to be something that can translate to any conceivable human form. After I did that, I got to this point where I couldn’t really play music anymore, I lost the use of my body and I’d lost the ability to write pieces of music that had a beginning and an end, so I started making this library of processes. The laptop became this random thinking musician I was trying to play along with.” He brushes aside the suggestion of AI, “Artificial intelligence is actual stupidity.”

What becomes clear as we talk is that Longplayer is not a passive work but rather a challenge, a sort of quest in time and space. In Zoroastrian culture, they keep Fire Temples where the flames have not gone out for hundreds of years. Successive generations must tend to them and in doing so the culture survives. In Japan, the Ise Shrine is torn down periodically and rebuilt. This is an act of seeming madness to the capitalist utilitarian worldview, but genius as it forces people to retain the knowledge of how to build wooden temples as well as embodying ideas of transience and the cyclical nature of life. It has done so for at least 1000 years. Longplayer possesses a similar spirit, “There is this social side, with people taking responsibility for looking after it,” Finer says. “It goes back to the Hackney Empire in a way. The embodiment of tradition and responsibility, and how it replenishes itself.” Future custodians will be keeping something alive then that is both tangible and intangible – a piece of music, or music itself, an idea, a way of life, a lifeform, or a form of communion.

Finer is wry about the Longplayer’s journey so far. It was originally housed across the Thames in the cursed Blairite omphalos of the Millenium Dome, now the O2, where visitors could walk through the human body, visit the MoneyZone (sponsored by the City of London) and wander around a host of other gaudy curios. “My zone was full of all the people frazzled from the other zones” Finer laughs. “It became the chillout space.” Longplayer found a new home across the water, in what was formerly the Experimental Lighthouse, where Michael Faraday worked on optics and lighting. The ultimate plan, though, transcends a single place and even a single form, ensuring its survival even if London is underwater or a scorched mark on the landscape. Adaptability is key. “The score can be realised in different sources of energies and technologies, and in the revival of performances. It’s translatable into many different forms. There is always a means. You can even sing it. If there is nothing else left, there is our breath.”

And at the end of 1000 years?

“It never ends. It just begins again. Like the rain cycle… or Finnegans Wake, where the last line is the first… ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay…’.

More information on this weekend’s performance can be found via Longplayer Live – Roundhouse. For discounted tickets, please go here and enter the code 10NGPLAYERRH