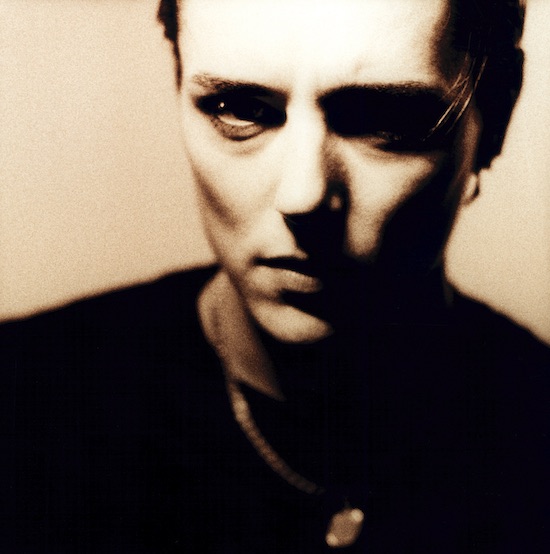

We first meet inside the door of her PR’s office, as Covid looms, during the floods. Jehnny Beth steps in from the teeming North London street, a delicate rock lord in black: oversized denim shirt with silver collar studs, pressed black jeans, slicked back hair. She looks at me uncertainly and I feel slightly guilty for arriving before she’s had time to catch her breath. Then she offers to carry my bags up the stairs, a true gentleman.

Not that either of us abide by a gendering of gallantry, as she tells me of her image: "I don’t really think of myself as a man when I’m doing this." Yet a tough pomp trusses Jehnny Beth’s new album, To Love Is To Live and her forthcoming book of erotic stories with photography by Johnny Hostile, C.A.L.M. She is a practiced interviewer and interviewee – but her polish doesn’t evade difficulty. Rather, as she continues our conversation from Paris, it allows her to civilly lock horns as we discuss artists who dare not to please. As she sings in ‘Innocence’, "Not my duty to give you shelter/Not my duty to give you hope."

C.A.L.M. (Crimes Against Love Memories, released via White Rabbit books this July) presents adventures in gore, piss and abject passion with a forensic detachment that recalls Bataille, De Sade, Anais Nin and Patrick Suskind. On the other hand, the surreal, menacing soundscape of ‘To Love Is To Live’ is a dark pop drama. Throughout, adrenaline-fuelled drum machine, siren synth, amorous brass, street voices, and a ticking clock underpin Jehnny Beth’s gripping vocals. Soaring from sorrowful whisper to Enya-like harmonies, creeping from cold proclamation to crepuscular beast, she’s never sounded better. Melding electronica, punk, jazz and noise, she skulks through these songs of doubt – of romantic love, of the self – with a rent-boy glamour. And just when the gleaming production feels perhaps a little too controlled, she slashes its compression with a vomit of emotion in the cyberpunk thrash of ‘How Could You’. She’s equally piercing as we discuss her struggle to create a space, in book and album, free of social conditioning.

For me, a recurring theme unites your album and new book, C.A.L.M. You seem to suggest that by being ‘sinful’, we reclaim innocence. Your opening song, ‘I Am’ and the narrator in the story ‘Bitching’, both speak of "burning inside" – and this burning is far from ‘wrong’. Rather, the dogging, the group sex in the story, is an act of love. ‘Burning’ feels like a metaphor for purification. And burning turns up again in the song, ‘We Will Sin Together’. Elsewhere in the album, you sing, "I’m done with trying to fix what’s wrong" and "your safe is my danger". So, I must ask, what is ‘sin’, for you?

Jehnny Beth: [Laughing] That is probably the best introduction to an interview I’ve had. You’ve really brought together the book and the album. When I wrote those lyrics in 2016 and 2017, they were about survival. I felt bereft of my own self. A lot of reasons behind that were to do with extensive touring. Also, the first time I came to London, I was 15. I never really looked back. I accomplished a lot with Savages, in terms of finding an artistic identity. But I found that what was burning inside, from being a teenager, was that question, "Who am I?"

I grew up as a bisexual although, despite my experiences, it took me a long time to name it. It created the anxiety of feeling I was living a lie. As a bisexual, whether you’re with a man or a woman, you’re always excluding the other part of yourself. In my younger life, I even desired to kill myself because the pain was too strong. Music saved me – and my relationship with Johnny Hostile, which was very open-minded. There was never anything we couldn’t talk about.

Sin, as it’s been told to me… My grandma is very religious but my parents were not. My sister and I are the only ones in our family not baptized. This caused quite a stir with my grandma. She bought me a Bible and cross and took me to church. I would pray every night through the Virgin Mary. I loved the discipline and the rituals. But I think the conditioning that was imposed on me is that what happens in your mind, whether or not concretized, is a sin. They [the Catholics] go deeply into your brain and are already closing doors, there. Through my art, I was trying to open those doors.

I wanted to write a book of erotic fiction because I feel fantasies should be free of sin. They shouldn’t be attached to any social or political stigmas or be constrained, because they are between you and your mind.

Speaking of social stigmas, there’s a tension, in these new works, between the hidden self and the self we display, or perform. In ‘The Rooms’, for example, we encounter the seedy boudoir, "the men who wait". Similarly, your stories suggest that only in private spaces can we make our world.

JB: Yep. It’s my refusal of unity as the chief goal of mankind. Intimacy is the only solution, the only safe place for self-expression.

In ‘Heroine’ you say, "All I want is to be the woman you never see". Who is the woman we never see?

JB: [Much laughter.]

Is she there, inside you, or not?

JB: Ah well. She must be there. I think that, although it’s a very complicated world, it’s getting simpler, in its language and in its message. We present human beings with one layer of morals, not distinguishing between public or private.

But we are a universe of multiple identities. We are more complex than we may think, or how we are represented. Art has a duty to show those layers. The woman I see, everywhere, is a woman whom we want to speak about other women. Especially women artists. The idea of a woman artist who talks about humanity, rather than just women, is more interesting to me. As for ‘the woman you never see’, I want this woman to be considered as an artist, first and foremost, an independent individual, not here to represent every woman on this planet.

In the album, you play different roles, with the pitched-down voice…

JB: The unconscious voice.

The lonely intimacy of your voice and piano in ‘The Rooms’, is particularly touching, within the album’s heroisms. The synth takes over, but, as with Bowie’s Blackstar, the piano ripple runs on. Bowie’s percussive piano, theatricality, his brass, street sounds, the drum and bass rhythms – he’s a huge influence on this album?

JB: Yeah. Of course. I couldn’t help it.

Can we talk about what happens when we explore art in a long-term relationship? You created C.A.L.M. with Johnny Hostile.

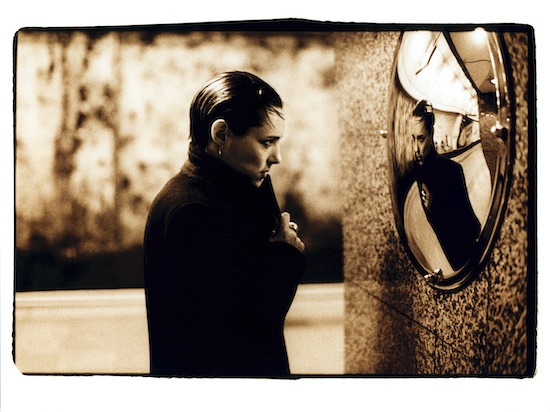

JB: I was inspired by the photos he took. When we moved to Paris, three years ago, he started taking photos of our friends, our private life. They were anonymous – and anonymity, these days, is precious. In the age of the selfie, faces everywhere, suddenly, you cut off the heads, so to speak and – boom – the freedom is there, the body expresses itself. Everything is fun and amicable. You liberate the body (and therefore) the conversations.

So, you decapitate the social self to reach "the woman no one sees"?

JB: Of course! Because the repression is so huge. Even the self-repression, the conditioning passed through the parents and grandparents. Baudelaire said an artist has no mother and no father. You have to find a space where the social-political conditioning is not there. If you find that space, you can safely explore who you are – and that can be in a relationship, too.

The experiences in C.A.L.M. will seem subversive to some: sex with strangers, anal sex, B.D.S.M, voluntary coercive sex and even cannibalism – is it possible to be truly safe, while feeling danger?

JB: Yes, because of the power of the imagination. I got interested in hypnotherapy for a while and how if you imagine something, the brain thinks it’s real. You can have experiences – by reading books, for example – in the imagination, then put them down. I’ve never tried drugs but if I could stop the effect like that, with a snap of my fingers, I would take a lot of drugs. By imagining things, we feel things. But also, the next line is, "to love is to live."

"And to live is to sin."

JB: Yes. And in a way, for me, that’s the full title. You cannot live your life, if you’re afraid to be wrong. So, the idea that we will do wrong together, it’s like making a pact.

I saw a really idiotic poster, on my way here. It was saying, "true love will never ask you anything." It’s dangerous to say that to people. We should go into a post-Romantic era. We should stop thinking about romance in love or art. That’s why I don’t listen to pop music, or the 50s, Motown and so on – I can’t get behind the lyrics. We fall in love yet we’re disappointed because we think it falls from the sky. My goal is to try to reshape that idea. You can be active.

Yet there is a return to safety, in your songs and stories.

JB: Oh yes. Always. ‘The Millionaire’, in that story, goes back to his wife. I don’t know if you’ve read Kundera but that man, too (in The Unbearable Lightness of Being), is in love with two women but when he returns to his girlfriend and gets into bed with her, there’s that sensation, of safety, of warmth. And there’s love.

Is that something you’ve been able to work out, in your own life? To many people that may feel intensely desirable but hard to achieve.

JB: That’s why I want to talk about it. We talk a lot about women’s liberation but never the liberation of relationships. And you’re right, a lot of people do say, "I’d love to be free but I could never do it".

But also, how much fear can we take?

JB: Yeah, that leads us to the idea of the hero. The hero goes beyond his fears. But he’s often hated for that, because he reminds everybody else that they’ve been too safe. People don’t want to be free because it has a price. Freedom is not the absence of rules. It has rules but it’s your own rules. But to find them, you need to get out there and get your ass kicked.

So, there’s no easy route.

JB: No, I don’t think so. If you need to break down conditioning, jealousy, doubts – that’s work. That’s a commitment. A constant enjoyment of your life, that’s not freedom, to me. Freedom is to know yourself.

Then, for a couple to create something together and display it, as you’re doing – that could be strengthening?

JB: Yes. Where else are you going to have something like that? Who can compete?

Did you have any doubts?

JB: I think the couple is the last taboo. It’s linked to procreation and the family. The sacred couple! Johnny Hostile and I have known each other for more than 15 years and we’ve been a unit, a couple, a working relationship – I don’t even know how to describe it, there are so many angles. The pact, from the beginning, was that neither of us wanted to be in a normal relationship. Making music together was the first way to break down the couple routine. We were too cynical, both of us. We know that nothing lasts. Love stories break down. Intellectually, we loved each other, we’d found each other. Everything we’ve done, this book, our private life, is to sustain that. And the dialogue, that feeds into our work.

Everything in the world is made for couples: hotels, trains, cars, tickets – buy one, get one free. If you’re not in that pattern, you feel excluded. For example, people who live as a threesome, not as two, there is nothing for them. Also, a relationship sometimes is sexual and sometimes, is not. Sex isn’t a value of love. This idea that one person is supposed to give you everything, your support, your lover, be the father of your children… Sexuality changes. We’re not the same person, next week. That idea of fixing things is dangerous for eroticism and the imagination.

Going back to this idea of the hero… Your song ‘Human’, and your story ‘Raw’ both express a monstrous pain that, in ‘Raw’, tears itself apart, literally. In the song, you sing, "My brain is atrophied my eyes are going blind" and in the story, your narrator revels in "the blindness of penetration". Is it important to you to blindly pursue experience, regardless of possible damage?

JB: It’s play. When writing, or creating, it’s an object to play with.

I understand – it’s not like you’re going out to eat flesh – but in what way is imagining violence liberating, for us?

JB: Very good question. I think it’s dangerous to censor yourself. I have difficulties with the culture of ‘I’m a good person’. Artists, I feel, at the moment, can only have a voice if you are ‘clean’. Maybe I’m doing it as a contradiction, to go away from the way I feel a massive group of artists are going – when you enter a certain kind of distribution, censoring the dark side, words like ‘fuck’, ‘dick’, or showing the naked body. The artists I like do not hide that they are flawed. You need the dark words to claim the light. Rage is a really beautiful way to get to happiness. If you express the rage, the pain, you are able to know yourself better and be human.

The voices in your erotic stories, female and male, have an exacting, pedantic tone, recounting adventures with surgical precision. It’s one we hear in typically masculine narrators, whether Humbert Humbert in Lolita, Grenouille in Perfume, or Bronte’s narrator in Wuthering Heights. But maybe it’s not so much a masculine style, but a classical one, outside of time?

JB: When you find the form, then you can start writing. The first form I found was a story called, A Debt To Pleasure. The idea was Greek tragedy, Oedipus and all that. Those characters speak but when they enter the room, they say, ‘I enter the room’. I wanted my characters to talk but I didn’t want a conversational style. I didn’t want to name my characters or the time. I wanted, as you say, to make the story stand outside of time. Otherwise, the stigma of society, today’s morals, would jump in. I wanted to create a space that was free of the constant domination of group thinking.

I was curious about your presentation of what I see as the ingénue character and of passive women. In C.A.L.M, the photographs are all of women in BDSM costume.

JB: You know, to be a submissive is to hold ultimate power. I don’t see ‘the ingénue’. I don’t feel connected to that word.

Well, for example, the first song of the album speaks of being "young" and "innocent" and a couple of your stories open with female narrators speaking of being young. It’s the launchpad for the experience that follows, this condition of youthfulness.

JB: Yeah… I imagined that I would love to read those kind of stories when I was starting my sexual life. You need guidance – when I was 15 and reading Bataille or de Sade – you get into fantasy. I don’t see any passivity of any of the characters in the book. They are proactive. Even if it’s a choice of being submissive to somebody else’s fantasy, it’s a choice, it’s an action.

So, it’s not as simple as assuming that someone is passive because they choose submissiveness?

JB: No, because from the moment two people go through whatever the characters do in the book, there is this bond and trust. To create trust, it demands your full attention. Attention is energy and energy is action. You create a place that is safe for someone – that cannot happen without your attention being on the well-being of that person. That’s what love is, really.

We’ve recently seen you performing a severe masculine look. How does playing a man help you to talk more, as you said artists should, about humanity?

JB: To answer that, I want to reach for a story called The Inverted Man’ It’s a story of childhood trauma and how that bleeds onto your life and has an impact on your sexuality.

Initially, it was called The Inverted Woman. I was halfway through writing the story and I changed everything. She became a heterosexual man. I felt that women’s trauma is done. I felt there was more to be done, in a novel, with the figure of the heterosexual man. It’s kind of taboo. Men are still stigmatised when they cry, need consolation or are impotent. We are rarely intimate in how we ask men to speak.

I’m wondering what you’re able to express, playing an overtly dominant male, say, in the video of ‘Flower’, that can’t be expressed in another way?

JB: I have to say I don’t know. Maybe it’s better that I don’t. Those are feelings, figures and characters I have in my head that still have some secrets to me that I’m not ready to uncover. Maybe it’s not my role. Maybe if I knew, I would stop doing it.

I have role models that are male and women. On stage, I think of Jacques Brel, I think of Iggy Pop. But also PJ Harvey, Kim Gordon, or Electrelane.

Iggy Pop! To what extent would you welcome violent vitality among a live audience, in the way Iggy Pop provokes it? Could you enjoy it?

JB: Enjoy, no. I’ve had some violent moments with the crowd. I don’t seek violence, I don’t want it. But I’ve been pulled down and I’ll come back on stage and say, hey, this is not acceptable, don’t do this. Or I see someone being mean to those around him and I tell him to stop it. I think of Nina Simone, you know?

I remember one Savages gig, with this punk in the room who threw glasses at everyone, including our guitarist. I stopped the show and told him to fuck off – the gig is not starting until you leave the room. And he got booed by the whole crowd, this big guy with a massive Mohican. It’s a matter of understanding that you have created this space, it’s your power. I try to remember my light. I have impact. I can decide.

There’s always going to be someone, a man or a woman, who tells you that you’re making a mistake. They say, all the time, ‘oh, you’re a strong woman, do this and you’ll be like a strong woman’. Then you speak with your own voice and they say, ‘you’re making a mistake’. You say, ‘but, I thought you liked strong women?’

But as you’ve said, it’s the artist’s role to uncover layers of humanity. To do that, you sometimes have to step outside the crowd.

JB: That’s what an artist does.

To Love is to Live is out now; C.A.L.M. out 9th July via White Rabbit, check tQ in a few weeks for an exclusive extract.