Best remembered by much of contemporary middle-aged England as the soundtrack to family road trips, Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds is not the kind of thing you bring up among your highbrow friends for muso points. But its simplicity and naivety give it a unique form of accessible entertainment value that has seen it survive the record collection clean-outs of countless music-lovers who grew up with it. It was prog-by-numbers; completely out of sync with the trends of the day but somehow took off and became a shockingly successful commercial hit, staying in the charts for over five years.

Much of its appeal is now nested in that aforementioned nostalgia, and it must be said that the work has not weathered the years with grace, but there is something joyful in the at-times silly leitmotifs, the Grade-A ham provided by guest actors like David Essex and the almost adventitious presence of the commanding and honeyed voice of Richard Burton in the lead role.

It has been described in some very opposing terms since its release 35 years ago. Ridiculous, genius, indulgent, innocent, a careening, bloated prog-drenched behemoth, but glorious in its own way. Whether you see it as a guilty pleasure, a stroke of brilliance or even a cause for white-hot rage directed at the general record buying public, this is a work that benefits from always eliciting an opinion – not to mention spawned video games and a number of equally grandiose stage shows that have kept its composer in the green for years.

Jeff Wayne has had a strange and varied career before and since the release of the album. He’s written gin jingles, newsroom soundtracks and even produced tennis-related television and literature. But …TWOTW is by and large his crowning achievement. Just like the H.G. Wells original novel and the Orson Welles panic-inducing radio broadcast, the version produces an interesting social commentary and a source of terror. In particular the strange talkbox “Ulla!” cry of the attacking Martians set many bell bottoms a-quiver in its day. Some of the themes however, particularly the ‘Eve Of War’, are so repetitive that you will gladly welcome the next guest actor hamfest. [‘Horsell Common And The Heat Ray’ is an unacknowledged masterpiece, Ed.]

The cast list boasted the strange mix of Justin Hayward (of Moody Blues fame), Phil Lynott, David Essex and theatre dame Julie Covington among others and was topped off by the inimitable Burton, who apparently signed on after being handed the script at a New York stage door.

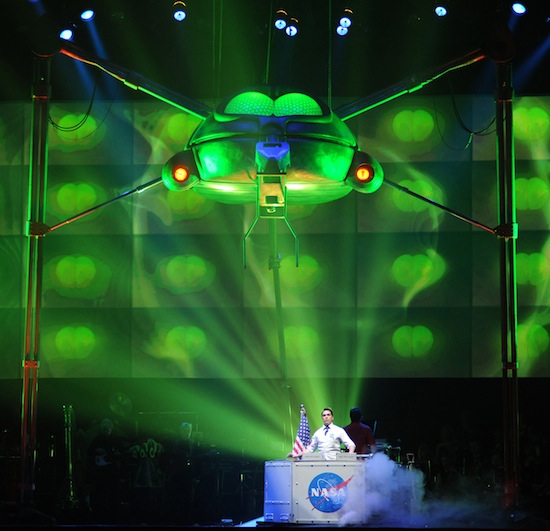

Since the original album, the project has evolved with technology into an effects-driven stage show, first featuring a digitally-constructed holographic head of Richard Burton and most recently full-body holography of Liam Neeson interacting with live actors and running from giant stomping metal contraptions. All is accompanied by a string orchestra conducted by Wayne himself. Self-indulgent? Yes. Overblown? Maybe. But even in these ways it remains typical of its retro futurist, progressive rock roots. And there will always be a market for that, be it nostalgia-based or not.

The latest stage in the life of …TWOTW was a rerecording of the original album with added sections and a whole new cast including Gary Barlow, Jason Donovan, Ricky Wilson (of the Kaiser Chiefs) and Neeson. The subsequent performances were the most successful the production has experienced. But there will be yet another “new direction” for …The War Of The Worlds in the near future, for which the details are still under wraps. What is known is the 70-year-old Wayne says he will step off the podium with a heavy heart for the last time in 2013.

How were you first introduced to the H.G. Wells story?

Jeff Wayne: I was first introduced to the story by my Dad in fact, back in the 1970s when my career was really just starting out as a composer/producer/keyboardist, and he knew I was looking for a story to get passionate about. So we started reading lots of different books, and not just science fiction. I was touring with David Essex and we were enjoying a lot of singles and albums and I was a keyboardist. And literally the night before going out on one of the tours with him, my dad came over and handed me this book by H.G. Wells. So I read it while I was away on tour and it was the first book that jumped out at me as the sort of piece I was looking for to interpret musically. That was really the beginning of it.

So if it hadn’t been War Of The Worlds, would it have been a different book?

JW: It certainly would have been a different book, and I do recall being impressed with Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, Wyndham’s Day Of The Triffids, Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World, and several others, but for one reason or another they all sort of fell away in terms of what I thought would be the right approach to a musical interpretation. It was The War Of The Worlds that really hooked me.

How close was the final project to the initial vision you had of it?

JW: Well I think it was pretty close because one of the things that a lot of people wouldn’t have known is that H.G. Wells died in 1946 and this was the 70s and his book was still in copyright, in fact it still is. So while I had found the book I wanted to interpret musically, one couldn’t do it without finding out who was in charge of the estate of H.G. Wells. It took us about three months – there was so internet or email in those days – and when we eventually found it it was agents of Frank Wells, who is H.G. Wells’ son and the rights had been left to him. Frank had agents representing The War Of The Worlds and so I presented myself to them explaining what I wanted to do and they sold my dad and I all these rights because I was the first one who had come along who wanted to stay true to what H.G. Wells wrote, which was this very dark Victorian tale. Every other version that had been done – even since that time – were set in contemporary America, and while the core idea of the alien invasion was still there, it didn’t reflect very closely to the themes and storyline that H.G. Wells was writing about. They didn’t know what I had been doing up until then as I was relatively new to the music scene, but it was just that fact that impressed them the most.

But did the final version turn out exactly how you had envisioned it?

JW: Yes, definitely. I was very proud of it when it was finished. I had no idea it would have any commercial acceptance by the public, by critics, or awards or anything like that. It was just something that came out of me, it was an opportunity as a young musician to express myself in the way that I felt. I was starting out with a blank canvas! And here I am all those years later talking to you about it. It’s resonated way beyond my wildest dreams.

I know you’ve told the story many, many times, but can you please tell me about bagging Richard Burton for the role of the journalist?

JW: The role on my original recording of the journalist was this man who had survived an alien invasion some six years or so earlier. So he’s telling us in 1904 about his story of survival, and he’s recounting it for his newspaper. It’s the one role that is pure acting, so I was looking for a voice that, the second the listener heard it, would have them sink into our world. Richard’s name was at the top of what was a very short list of people, and it just happened that a friend of mine had just come back from New York and mentioned quite casually that he’d just seen a play called Equus with Richard Burton and he was brilliant in it. And I thought “Crumbs! That’s the man I want to try to get to, but if he’s doing a play he’s probably doing eight shows a week." So I just wrote him a letter introducing myself and a copy of the script and asked him to be our journalist. I sent my little package to the stage door of the theatre that he was appearing in and just hoped that the stage doorman would just hand him my package, and he would have some time to read it and consider it. I didn’t have much hope in truth, but only two or three days later we received a call from a man named Robert Lance who was Richard’s manager and he said: “Richard loves the idea! Count him in dear boy." Those were the exact words are what I’ll always remember, because I was so shocked to pick up the phone and hear that. So that’s how it really began, and Richard went from Equus in New York to Los Angeles to start making a new film so we travelled with our equipment to Los Angeles instead of waiting many months for him to finish the film so we could stay on our schedule and that was it.

What was it like working with him?

JW: He was unlike what I expected, because besides being recognized as one of the world’s greatest actors with an amazing voice, his private life overshadowed a lot of those qualities. So I wasn’t sure what to expect. But when he walked into the studio he was the most delightful man you could imagine and we got along famously. Just to give you an idea of how great he was: he had a contract with us saying he has to do five days in the studio with us as needed, each day being up to 12 hours, but he did it in one day. All of it, apart from some repair work he came back to do a few months later which only took about three hours. He nailed it.

Can you tell me about creating the holographic head of Richard for the show?

JW: When he passed away in 1984, Sally Burton inherited his estate and our contract was only for audio recordings. So in order to bring him back to life, Sally had to agree that she liked the idea and we had to strike up a deal. She was thrilled with the result. She lives in Perth now. And when we did the second tour in 2007 we did go to Australia and New Zealand and she came to see the show and was blown away by it. The idea was to bring Richard back to life, to have this very commanding voice attached to a talking head, as it was known. If you were a living actor, the way you would create that effect is by sitting in a chair and being clamped from four sides – top, bottom, left and right – making it impossible to move your head sideways or up and down. You can wiggle your nose, you can close your eyes, that’s it. Then you’re filmed straight on and you create whatever role you’re creating. In the case of Richard who was no longer alive, we had to work with an actor who had certain facial attributes that Richard had and he had to learn to mime the sequences that Richard performed and synchronous to Richard’s voice. But then when those sequences were filmed, the real work started because there is a whole team of computer operators who then had to take those film sequences and turn them into Richard Burton. They worked to still images that we provided of Richard at an age when the journalist in the story was meant to be. So it was quite a long process, and it was very successful. We stayed with Richard’s performance for five tours and it’s only because we expanded the story, and with Richard’s work being finite, I was very lucky for a second time to wind up with Liam Neeson on the new recording. Richard had 77 sequences whereas Liam has 90.

The original album also had other top notch guests like Phil Lynott and David Essex. How did that all come about?

JW: All the people on the original album were highly successful in their own careers. David was someone who I had a long established working relationship and good friendship with. Julie Covington was in Godspell which was a play David was in and that’s how I met her. But Phil Lynott, Justin Hayward, Chris Thompson, these were people I didn’t know. I was thrilled that they were interested because they each brought their own sort of magic, their style and performance and singing.

It seems as though it was all a very professional and organized process, which certainly isn’t how many other rock albums in the 70s were made…

JW: Well making music isn’t a precise art, you can only be as prepared as you can, writing and arranging for the studio, but it still relies on those type of musicians who I’m hoping will bring in what their reputations preceding them would suggest. Many of them I worked with on other things, including a lot of rock and electronic and even some jazz recordings, so we knew each other well enough to start on a project like this, but it was an unknown territory for sure. And then when the guest artists came in, it was similar as most of them were from the musical world, so when you get Phil Lynott, a musician in a hard rock outfit like Thin Lizzy, you get someone whose lifestyle and attitudes towards music are coming from that world, which is exactly what I wanted for the part that he played. He played Parson Nathaniel who goes mad and thinks the Martians are the devil, and he loses all faith in mankind. Justin Hayward from the Moody Blues has this magnificent, classically English, but rock voice and I was just thrilled to attract him to be the sung thoughts of the journalist. David Essex was a common soldier and artillery man, and knowing David I knew he would bring in just the right style of acting and singing to it. But I had to demo everything for everybody. I couldn’t just call everyone up and tell them to get in the studio and start singing, it wasn’t that at all. I had to convince them that they were right for the role and get them keen on doing it.

I’ve heard there were a couple of big stars whose contributions didn’t quite make the final cut… Is it true that you had both Carlos Santana and Paul Rodgers involved?

JW: Briefly, absolutely. The Martians had this ultimate weapon that they brought with them, the heat ray, and I interpreted that as a guitar piece. Different melodies and riffs and hooks. I had wanted a particular style and Carlos was up for it. He had spent a day in the studio with me and things were going well – he was due to come back for a second and maybe a third day – but his manager took a view of the contract side which had changed between the time they agreed to do it and the end of the first day. Unfortunately it all fell apart because of certain requests in the contract which we couldn’t oblige with. With Paul Rodgers, he spent a day in the studio trying out the role of Parson Nathaniel, the role that eventually went to Phil Lynott. He was sounding, in his style, fantastic on it, but I think he must have thought he was going to be acting live with Richard Burton and Julie Covington in the studio because he took a view that maybe this wasn’t for him on that basis. But the singing part, as far as he went with it, was superb. But these things happen! It’s partly why you do demos for people and hope things work out, and sometimes they take the unexpected twist or turn.

Will these recordings ever see the light of day?

Uh, no. They exist on my original multi-track tapes. We digitized everything years ago, but the original tapes have the performances on it as far as they went. They weren’t complete, but the end result is that because they never completed the roles, the contracts were never completed along with them. I wouldn’t ask. I think would be disrespectful for the reasons they didn’t wind up on …War Of The Worlds. I think it should be left as a bit of history, a nice story to tell, it’s absolutely true, but I would never release them even as outtakes.

There is so much interesting instrumentation on the record. What particular sound are you most proud of in retrospect?

JW: I think the ones that have always come back in terms of feedback or reviews, things that I didn’t even know connected so much, are more the alien sounds. The way I combined electronics, which I knew how to do quite well in the days when synthesizers first started. Those things generally, but one sound particularly was the sound that the Martians make when they’re both terrorizing the earth and when they’re dying at the end and it’s a word that H.G. Wells created called "allu", but I turned it around to make "ulla". It’s a combination of a voicebox guitar and the performance of the musician that played it. And I’ve heard of many people, even at our shows that get terrified by it. It’s a gigantic sound and when we do it live it’s in surround sound so you can imagine the impact no matter where you’re sitting in the arena.

The original story was created by H.G. Wells to have scientific accuracy and broadcast by Orson Welles to produce authentic terror in listeners. Was this something you took on consciously as well in terms of your sound landscape?

JW: Well I was aware of the 1938 radio production that, because it was live radio, did scare a lot of the public who was listening to it. I thought that was because it was radio and it was the medium of the day and the imagination of anyone listening to what they believed was a real life event. The way they did the broadcast was very clever, it was set in a hotel with a little popcorn orchestra playing popcorn music and it was little news bits to start with, just little interruptions like “Just a little news alert, a sighting has taken place, nothing to be concerned with, and now back to the music." Then the music would play and then there would be another little interruption and then it grew into the alien invasion. And it did scare people. But with me, I didn’t want to lose the essence as how he wrote it so I set it back when he wrote it in Victorian times. Therefore it wasn’t a live event from that point of view, but it was also a recording, so I never imagined that anybody picking up a record would be scared by it. But I’ve been amazed by, and I’m not exaggerating, a number of thousand of letters or forum posts that have said people would turn off their lights deliberately to be scared while listening to the album. And I think when we did the new recording of it last year, it’s happening all over again because the technology has advanced so the quality of the sound and power is that much more dynamic and the tours themselves have the same impact in a live sense. But I never dreamed that it would happen.

Do you compartmentalize the different versions of the project or do you see it more as a fluid evolution with technology?

JW: What actually convinced me that it was worth doing a new recording – I had originally thought if it was broken, why fix it? – was when I took a family holiday after the 2010 tour and I took with me and read for the first time in years the original script I’d done with Richard Burton and all the other characters, and it reminded me how much material didn’t wind up on the double album. Then it was because it was the year of the vinyl disc and there was only so much material on each side. But the fact that there was all this interesting storyline that got cut, it got me thinking and I was convinced that the story, particularly because we had tours we were committing to, that expanding the story would motivate me to expand the score and in contemporary terms it meant I was able to use all the technology of the day. Even the grooves of the music have changed since then and collectively there were a lot of new challenges. I hope that risk has paid off.

How do you feel that you have personally contributed to the legacy of Wells?

JW: I think The War Of The Worlds has survived so long now and I also know it gets read and listened to in schools around the world and at times my recordings have been used to introduce the story and get people aware of the story that was written in 1897. I know people, particularly in the United States, that only know the movies that have come out or the radio recording and think it’s a tale of an alien invasion in contemporary America. It’s nothing like that at all. If I have contributed at all I would be thrilled because I think it sets the record straight, so to speak.

So how did you got about getting Liam Neeson involved in the new show and recordings?

JW: Right after I concluded that doing a new interpretation was valid, I started the same way I did on the original, which was getting the role of the journalist filled first. It was very similar to what happened with Richard, I only had one real name I was hoping for on this recording and that was Liam. I love his voice and always have done, I think he is an amazing actor. We were able to meet him through an agent who represents his interests based in New York where Liam also lived when he’s in the States. We had to go there to meet him because he’d just finished two movies and was home for only a short time with his two sons. So we got on a plane very quickly and met him and it was only then that I learned from Liam that he bought the album when it first came out! He knew most of it and even started singing some of ‘Forever Autumn’ to me, which knocked me out, but he also said that at the start of his own career one of his first breakthrough roles was in a mini-tv series, and while he didn’t have the lead role, Richard Burton did. He used to watch on the set how Richard worked, listened to his voice, and when …War Of The Worlds came out all those years later, he remembered how he started, he went out and bought this copy, a cassette version. He’s a lovely man, I was so privileged to work with him and get to know him.

I’ve heard that you may have another A-lister lined up to play H.G. Wells himself in another new part of the show. Can you elaborate on any of that?

JW: It’s something I haven’t really been talking about yet. The idea is for this final arena tour is that I wanted H.G. Wells to have his say. It’s all written, I’ve demoed role, it’s a technological recreation of Wells, and how we present it is still in development. So if all goes well it’s true. We are talking to somebody, yes indeed, but there is also an alternative way of doing it, which is by using footage that exist of H.G. Wells. The role is in three big pieces set at different times, one is when he’s aged 33 which is a year after War of the Worlds came out, the next is 20 years later just after the first world war and then in 1945 just months before he died. He’s looking back and forward and he gives a good insight into why he wrote it, which wasn’t about a shoot-em-up-knock-em-down science fiction story, but it was actually making social commentary about the standing British Empire, about one’s faith and challenging certain things. It’s also about territorial invasion, which when you think about the world we live in today, not a lot has changed.

What other new things are being added to this new tour?

JW: Well every tour has tried to top the previous tour and we’ve tried to find natural ways to integrate technology, new musical content, or just a range of things from big items to small items. With Liam on the last tour, one of the ways you see him is in full body on stage and he’s interacting with the various guest artists playing the roles of people the journalist meets along the way of the story. Early on, there is an artillery man who on the new album was played by Ricky Wilson of the Kaiser Chiefs, and the man crawls into what he thinks is an empty house. He’s a bit disheveled and bloody because he’s just been with his regiment and they’ve mostly been blown away by the Martians’ first arrival. He’s one of the few survivors who gets away and he crawls into this house, which is in fact the journalist’s house who sees him, takes pity on him. And you have to keep in mind that Liam is in full body 3D holography. But he offers him a drink, and you see him pour a glass and he hands it to him the hologram to the actor live on stage. These are small moment that have had an incredible impact, more than we expected. Liam was actually a fine boxer early on in his life so he does a good job in the scene where the journalist knocks out the Parson to keep him quiet basically, and again you see this live on stage. It’s one of those dynamo moments where you step back and go, “How did I do that?!” We have a few of those, and they’re precision timed and the score has to be happening at the same time and all those other things. I think what makes …War Of The Worlds work generally is the integration of sight and sound.