Introduce yourself, Jamie.

“What?”

You’re meeting someone for the first time. How do you describe yourself?

“I wouldn’t. I’d just talk. When you meet people do you describe yourself?”

Say that hypothetically you had to.

“Hypothetically? Well I wouldn’t. So… there.”

He laughs. This is serious. The government are making you do it, Jamie.

“I’d say I’m an after-dinner speaker, it’s an area I’ve been meaning to explore… Look, I don’t fucking know. I wouldn’t. That’s a very funny question.”

He pauses, puts on a pompous voice and sets about lampooning himself.

“I’d describe myself as the poet of brokeback Britain!”

Brokeback Britain?

“Yeah.”

A gay cowboy-poet?

“Yeah, a gay poet.” He laughs a lot, smokes a lot too; takes another drag and plumes it up into air thick already with a dozen or so dead cigarettes (two days later he’ll postpone the start of his UK tour citing laryngitis).

Introductions… A few things are fixed – Jamie T is a straight, white, middle-class male in his early twenties. But so’s everyone else and they don’t receive Mercury nominations or sell hundreds of thousands of records. We need to haul ourselves closer – let’s meddle with the variables.

How do you think your music would change if you were gay?

“Oh, I don’t know man. God knows. I don’t know.”

What about if you were black?

“I don’t know either man. I don’t know what it feels like. So god knows.”

Jamie T’s not black, he probably isn’t gay either, and I am not god, but I probe and pester in this smoke-filled shed because I am a pop music writer, trying to find out who Jamie T is. Leave any mortal alone with new album Kings & Queens (or anything, really, that Jamie’s recorded) and they’ll tell you what Jamie T’s like before the first song’s done barking – you’ll learn he likes a drink, for example, or that he stays out late enough to miss the last tube; you’ll hear him crack wise and wry about the authorities and a cadre of outstandingly unlucky friends and acquaintances. But it’s a lot harder to get a sense of who Jamie T actually is – of his identity, rather than his personality. Surely that’s not too much to ask? For just an inkling of where his mind drifts when he’s stranded at Hampton Wick Station at 2am, or why he’s drunk rather than what he’s drinking; what separates friends from acquaintances when their luck’s so equally rotten.

Because you need that, don’t you? To know there’s someone there, behind the choruses, tall tales and likely lad chutzpah, struggling to say something unsayable – knowing a human’s made and is making those noises. If not? You’d give up. You’d shut your eyes and squeeze hard ’til you evolved into a rocket ship or a pylon or something.

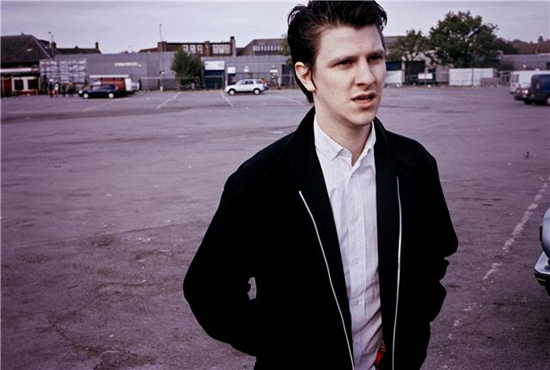

Here’s what else we know about Jamie T (né Treays). We know that he lives in the last house on the right at the end of a suburban cul-de-sac. We know it’s 3:30pm and someone’s upstairs whistling ‘People Are Strange’ in the shower, that the front room’s hung with drying laundry, conquered by a propped up Union Jack flag, DVDs and empty packs of Ribena and Mayfair Smooth scattered like war dead. We know it’s September 2009 and the leaves are still green. We feel the chill in the air, see the sky’s grey and forget the way back to the nearest tube, the last stop but one from the District Line’s southern terminus.

How long have you been living at this end of the train line, Jamie?

“I don’t know, three years? Touring confuses things. It’s taken ages to get this place sorted," he says, gesturing around us at that aforementioned ‘shed’, a home studio down the end of the garden soundproofed by his brother.

Where were you before you were here?

“15 minutes away, still in Wimbledon.”

What was it like growing up in Wimbledon?

“It was enjoyable, a nice area to grow up in. Just not much to do really. You just hang around, don’t you?

“I’ve got fond memories of making fun out of boring places, y’know? You don’t have anything to do, you make your own fun. I spent a lot of time skateboarding and playing football in car parks – everyone bringing their mixtapes and communing around a little portable tape player.

“We used to sit there for hours,” he continues, “people coming and going and that’s all I remember, really – a whole misspent youth in fucking car parks."

Can you drive?

"No."

That ‘misspent youth’ part’s fairly ridiculous, given that it is Jamie’s music. The skate-park was the last meeting point for slack youth before someone switched the internet on and turned the young and dead-eyed into dead-eyed hermits; the missing link between street corner and Facebook for the pre-pub, post-pube out-crowd. Anyone who was teenage and suburban at the last millennial turn knows the value of "just hanging around", and yearns for it desperately – for the hip-hop, drum’n’bass, punk rock it’d pour into your ears; things that sounded good to skate, drink or get high to. Then there were those other, hanging people, “coming and going” all day long, carrying with them house party myth, gabbling about the next one, trading phone numbers, insults, jokes.

Jamie T’s music still sounds like all of that; blaring – The Clash, Black Flag, Beastie Boys, Rancid; the jokes, insults, myth and drinking – though it’s ditched the dance music. Early, beat-driven efforts like ‘Ike & Tina’ and ‘Northern Line’ are relics.

“It’s four years on, you know? You’re not thinking in the same headspace.”

Treays doesn’t listen to dance music any more. He listens to Bob Dylan, The Wave Pictures, Bon Iver, Joe Gideon & The Shark – to story-tellers, an onward path he wanders himself though his subject matter still returns to that misspent youth, Kings & Queens overflowing with a cast of wildly irresponsible characters that drift in and out of shot like parking cars.

How important is suburbia to your music, Jamie?

“It’s hard… There’s a boredom in the suburbs that’s interesting to me. The whole… boredom of it.”

“You’ve got nothing to do have you? So you make your own fun."

He pauses a second, sets another cigarette on fire.

“I grew up here, so obviously it’s important,” he continues, “but it’s nothing to do with the place. It’s the people in the place, you know? I’m not patriotically London. I couldn’t really give a shit. It could be anywhere to me.”

Honestly? I find that hard to believe – what about “walking it drunk down the Strand" and "falling asleep on the Northern Line", the samples of Betjeman and the early shows at 12 Bar on Soho’s Denmark Street? What about Bob Hoskins walking along the Thames at night mouthing “she screams, calling ‘London’?” What about that?

“It’s not necessarily a fucking ‘I Love London’ T-shirt. It might be ‘I’m sick and tired of this fucking place’… ‘Put your hands up for London, I fucking hate this city’.”

Why?

“People are kind of rude here. They don’t say ‘Hello’.

“I love London," he says, weighing it up, "but it’s a love-hate relationship. I think everyone who grows up anywhere will love that place as much as they hate it.”

Recently, Jamie and his hometown have had plenty of time apart to think on their differences. A festival summer was followed by an Australian tour. He got home yesterday – tan-less, strangely – and now it’s back in the shed down the end of the garden, smoking expensive English cigarettes and sucking at the violet Ribena teat. It’s here, amid keyboards, computers, posters and a piano, that the follow-up to debut album Panic Prevention was written and produced, in tandem with Ben Bones, Jamie’s best mate and drummer with live band The Pacemakers.

The Pacemakers exist because Jamie craved “the energy you get with a band” after three years alone with his acoustic bass. Songs made solo were redrawn from bedroom demos into fuller, thicker and – yeah – more energetic things, but you can’t help but feel that somewhere along the way something quite precious was lost. Maybe it’s the inevitable dilution you get when others enter that little world you’ve eked out on shit samplers in the privacy of your bedroom, in between cups of water gone stale after endless 4am overdubs, intimately connected wires and the somehow erotic wink of red LEDs.

“You want intimacy, you play songs on your own,” argues Jamie. “When you want energy, it’s the band. I still love the silence of acoustic shows, though.”

A band robs you of that, and it’s a shame in this case, because many of Jamie’s finer moments – when a sense of who he is really begins to emerge – arrive in the space and shadow of that silent acoustic intimacy. ‘Back In The Game’, ‘Livin’ With Betty’, ‘St Christopher’ from the recent Sticks ‘n’ Stones EP, ‘Emily’s Heart’ from Kings & Queens: all sore, torn and sullen. Finer still – and even rarer, now – are those moments when intimacy and silence seem there even when the acoustic guitar isn’t. Seek out the early, Logic-produced demos of ‘Ike & Tina’ and ‘Dry Off Your Cheeks’, or late-night B-sides ‘Meet Me On The Corner’ and ‘Back To Mine For A Moonshine’, both of which conjure the sort of privacy you find alone in the passenger seat of a humming car as the rain hammers down and the driver door slams shut (‘Ike & Tina’ sounds like petrol fumes and gutter oil).

Unlike its predecessor, Kings & Queens is written for a band, songs like ‘Spider’s Web’ and the excellent ‘The Man’s Machine’ jubilant and charged, but the man behind them seems more reluctant than ever to write either by himself or about himself – though the way the stories are told is familiar – Joker! Rascal! – Treays seems to disappear, gradually, in the details; overwhelmed by that familiar cast of characters that buzz and booze around him like poor, doomed flies.

The people you write about always seem to be quite unlucky, Jamie, like they’re fucked up on something or other or escaping from mental institutions or getting shot…

“Movies end quite tragically, don’t they? It’s harder to write a happy ending. There’s something about bad luck that’s really a fucker, isn’t there? People are drawn to that.”

Has anyone any ever recongised themselves in your songs?

“They normally get it wrong to be honest. Someone said to me once, ‘Ah you know this guy I know’ and obviously that guy’s been out there telling his mates I’ve written a song about him. Fucking liar.

“I tend to leave mates’ names out of songs anyway – it’s mean isn’t it?”

Do those mates treat you any differently now?

“No, they’re my mates, not pricks.”

Do you ever think of yourself as a voyeur?

“Na.”

But you’re looking on, watching people…

“I’m not sitting there with a note-fucking-pad. ‘Voyeuristic’ makes me think of some weird, sexual thing – sitting in the corner going [leers].

"Story-telling, I suppose, is voyeuristic to some extent, but I’m involved."

How?

“I know what the fucking songs are about, but I don’t care to talk about it, because they’re quite personal to me. I’ve written the song. I’ve done my piece.

“I’m not sitting here trying to pour my heart out. I’m just jumbling things up and throwing them at the fucking page. I’m not trying to represent anything. I haven’t got a fucking manifesto here, y’know? I’m not trying to explain things to people. Whatever you think it’s about, it’s about.”

Isn’t that a bit of a cop-out?

“No – I fucking hate it when musicians sit there and tell you what a song’s about. I don’t wanna hear what your story is. You’re ruining my story. The one I’ve made up in my head. Why are you telling me? I don’t wanna hear it.”

Isn’t it important to show people who you are?

“No, it’s important to write songs. I’m not gonna sit here talking about what this means or trying to explain who I am… come on…”

What’s wrong with telling people who you are?

“Nothing, but songs aren’t all about me, they’re about other people, other situations, and me, everything involved in the whole fucking… thing. And I explain that through writing songs, how I feel or think about a situation.”

Can you understand why others might be sceptical about your background?

“Why’s that?”

Because people are always sceptical about middle-class kids who went to public school, especially when they get described as ‘social commentators’?

“Not particularly. I never wanted any fucking, social commentary, fucking, you know… hung around my head. I do music for myself. Anything past that’s just other people talking, you know? So I’ll watch myself rather than other people.”

You seem quite guarded when it comes to people talking about you.

“Uh huh.”

Isn’t that a double standard?

“Why?”

Because you talk about other people all the time.

“It doesn’t really matter ‘cause I write the songs, y’know? You’ve got to understand that I don’t write music for anyone, I write it for myself and that’s it. And I don’t have to speak to anyone or answer to anyone, about anything, because it’s for me, it’s for me and Ben.”

So what about this vision of you as ‘social commentator’ that some people seem to have?

“I don’t feel very political. I tend not to talk about it, ‘cause I don’t really know about politics.”

Almost every song on the new record mentions guns.

“Does it? Well guns can be metaphors for a lot of things. I’m not talking about fucking gun crime.”

What’s your opinion on gun crime?

“I’m not even answering that question.”

Have you ever shot anyone?

“Have I ever shot anyone? No. No, come on. I don’t think of myself as some ‘urban poet’. I think of myself as someone who’s sitting in a shed writing music with his mates and kind of wondering when someone’s gonna turn the lights on us and go, ‘What are you lot doing? How have gotten away with this for so long?’”

We’re done. Jamie lights up and slinks away with his earphones in (Bran Van 3000) and I trudge back to Wimbledon Park. Who is Jamie T? He’s the face staring out at me from a poster on the platform, the cartoon ghost just anonymous enough for his songs to haunt your hard times. He knows what he’s doing. He’s clever like that. And he’s you. And you. And you. And you. And – no, not you. Maybe.

Everyman for himself.