As the St Paul’s Occupy continues with rows of tents in front of Britain’s most eminent spiritual beacon, just a few hundred metres away on the south bank Jamie Reid, elder statesman of British protest graphics, is exhibiting. Parallels are obvious between the carnival of improvised anti-globalisation posters and banners evident on St Paul’s forecourt to the work of the artist who, through Suburban Press, the Sex Pistols, the Poll Tax and Clause 28 has been stick[er]ing it to the man for decades. In fact, he popped across the Millennium Bridge himself and left impressed by what he saw.

"Absolutely fantastic," he enthuses, sat in the Bear Pit, setting of his Peace Is Tough exhibition. "I think it’s great that, at last, people are finding the motivation to go and do things themselves. You can ask the whys and wherefores, but I think people have just had enough. The actual act of being there and occupying that space is a great thing in itself." He was pleased to be able to conjure from his briefcase a copy of an info sheet/newspaper produced in situ at St Paul’s.

One of the participants, Tzortzis Rallis, explained to me the significance of Reid’s oeuvre in that context. "We are currently working on the second issue of The Occupied Times of London. In a city with a rich history in protest graphics we thought it was important to challenge the narrative of the mainstream media. The principal rule of our design approach is to be as radical as the ideas of the movement. For that reason, a significant inspiration to our work was the punk movement and DIY techniques. We are using two different typefaces. ‘DIN’ has been used widely within multinational corporation brands while the typeface ‘Bastard’ is our design critique of the capitalists – ‘the modern fascists’. ‘The fascist regime…they made you a moron?’ Today the multinational corporations and the bankers, maybe?"

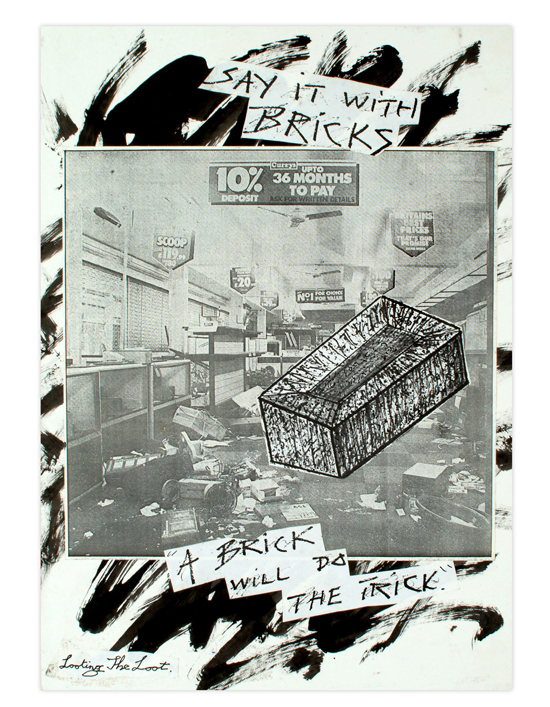

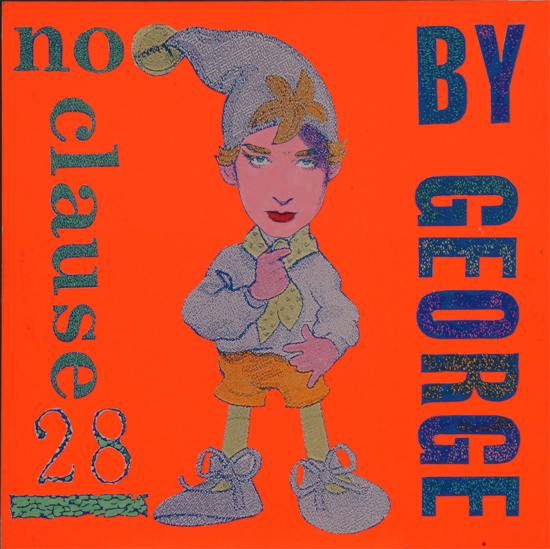

To Reid, the current malaise of capitalism and the response to it is both part of a generational cycle but also, perhaps, something more substantive this time. "It comes and goes. Obviously I get sick and tired of talking about the punk scene in many respects. But the whole scene I’ve been involved in visually, the Criminal Justice bill, the Poll Tax, the God Save Our Forests things, it’s just a continuum. I think it’s quite proven, with the Suburban Press stuff I did, especially the ‘Last Days’ stickers [which, as far back as 1973 adapted storefront ‘sale’ notices warning that ‘this store will be closing soon due to the pending collapse of monopoly capitalism’], how pertinent that is to now. People seem to realise that this time it really is a clash with the system. More and more people are articulating that. They’re seeing the con of it, realising all their rights are being taken away continuously since Thatcher, and Thatcher’s legacy. What they’ve done to this country is an absolute disaster, particularly with regard to education."

Reid’s own background included an entirely fortuitous degree course in his native Croydon where, incidentally, the worst of the recent riots occurred. "Croydon always had that youth culture, from Teddy Boy times onwards. It’s always been there. "I don’t [go back there] so much now that both my mum and dad have passed away. I did go back to Croydon to do a talk at the art school which was really enjoyable – just in front of the art school is a plaza and all the kids were skateboarding, which they’re probably not allowed to do, which was great. Again, that’s where the image ‘God Save Our Yobs’ comes from. I’ve got a 19-year-old daughter. We really have demonised our youth. But yes, I do feel a total affiliation with what’s going on at this show and what’s going on with the occupation campaigns."

Reid is keenly aware that the educational opportunities he once enjoyed are going to be very limited for young people now. "Oh yeah, the arts, music, everything young people love and should be doing is being taken away from them. It was a toss-up for me between going to art school and becoming a professional footballer. I’d failed my exams, but in those days you got a grant. What I loved about Croydon was that it was half technical college, half art school. So I could go play football with my mates at the technical college at lunchtime. But yeah, with all that’s happened since, it does make you wonder what we were protesting about at the time! In retrospect, that I could go to art school, get a grant, without qualifications? If I think of my contemporaries who were there like Malcolm (McLaren), Sean Scully – none of us would have got there through [today’s] education system. How many people are there like us?"

"Most of the Suburban Press situation was spontaneous," he continues, discussing the community printing press he established in Croydon, "affiliating with the radical groups that were around in South London. There was a lot of synchronicity with things happening all over the place. After Suburban Press I went to stay with some close friends of mine in the Isle of Lewis. A big part of me wouldn’t have minded just staying on doing what we were doing up there, which was basically crofting." Then a telegram arrived from old friend Malcolm McLaren in 1975 asking him to come to London to help with his new Sex Pistols project. "Me and Malcolm knew each other really well and we just got on and did what we did. It was an attitude. In many ways, I find the Suburban Press stuff far more resonant now than I do the Pistols. It’s funny for me, because yes, the Pistols were part of it, but I’m more proud of things I’ve done in music with other people, like the stuff with Afro-Celt Sound System, which is a whole different ball game. Or the Dead Kennedys or Transvision Vamp or the heavy metal band I worked with called the Almighty. Some of the artwork I did for them I’m probably more proud of than the stuff I did for the Pistols, but because the Pistols were what they were, that’s what gets hung around your neck."

So, does Reid believe that capitalism is not necessarily the enduring, immutable force in history we are led to believe? "Well, [not] if you read Tom Paine. And people should! That’s just as relevant now. I met Richard Attenborough, believe it or not, a while back, I think it was his 80th birthday. Here’s a bastion of British film and he said his biggest regret in his whole life was never being able to raise the money to tell the story of Tom Paine. How many people in this country know about Tom Paine? He’s so relevant to what’s happening now. What about the romantic poets? What do you they do to them? Make them so they are English Romantic Poets rather than the real radicals that they are – Wordsworth, Coleridge, amazing people."

Does he feel his own image being shaved of that radicalism? Even doing this, there must be some element of compromise and concession? "Always," he ponders. "As much as I can, I try to control the situation, particularly with the exhibitions." And is he comfortable with the whole concept of the promotional interview? "Probably less so than I used to be!" (laughs) Because he’s said enough on certain topics? "I obviously do get sick of the Pistols thing. But I also get sick of – it happens far more to me in this country than others where I’ve exhibited – the ‘how does the esoteric work?’ question. ‘How can you do that, isn’t it contradictory to the political work?’"

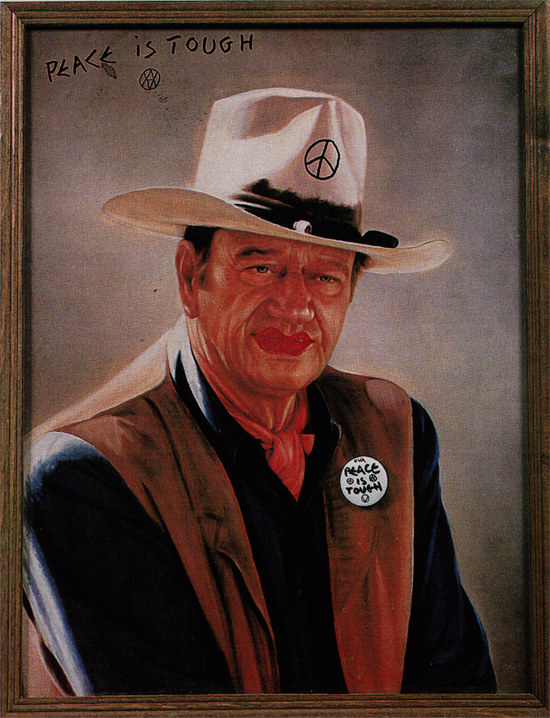

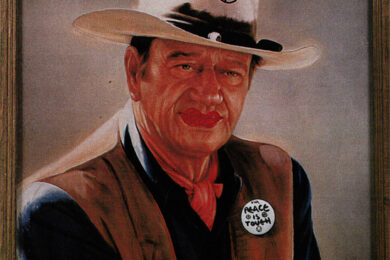

The Pistols hang not just around his neck, of course, but prominently around whatever gallery space he agrees to inhabit. He confesses that he fears he concedes too much space to punk-era work, but it comes with the territory. And he’s suspicious about galleries in any case. "For me, when it works at its best is like the work I did in Derry in Northern Ireland. We did a whole major retrospective, but it entailed loads of talks, workshops and creating an environment where hundreds and hundreds of people came to participate, that whole concept. You can’t get away with that in established places. And some of those people are behind the Nerve Centre in Derry, which might be the best arts centre in Britain. Then, on the tenth anniversary we went back to Derry and did a similar thing. Funnily enough, it reminded me of the ‘God Save the Queen’ scenario. A Russian laser artist Alexei Blinov was going to project the image of John Wayne [from Reid’s ‘Peace is Tough’ graphic, depicting the emasculated Wayne in lipstick] over the river. Then that got banned. And suddenly it was all over the television and front pages. We finished doing that and six months later I got a whole package through the post about an international peace festival, and on the front of it was the ‘Peace Is Tough’ image. And in a small way, that is so outside the culture of punk and the culture of art galleries and it’s wonderful."

Some of the works he’s proudest of are his collaborations with Steve Lowe at the Aquarium L-13 gallery, which also represents the works of Billy Childish and Jimmy Cauty. "I’ve got to really love and respect Jimmy Cauty, because what he did with Bill Drummond and the KLF was amazing. Bill did that book beforehand, ‘How to Have a Number One Record’, the whole scenario about burning a million pounds on the Isle of Jura … it’s so important to do things like that in a fresh, clean, new way. It would have been so boring had they [the KLF] been punk. It was so much better that they did it with dance music. I find it sad now, in many ways, that every young band you see is looking back at punk and trying to copy it. It’s time to be experiment and be creative, which hasn’t really happened since the 60s. We need a whole new way of playing music and doing art."

So there are reasons to be optimistic. "Oh, yeah. Always. Very much so. That was the way I was brought up." So does the fact that the St Paul’s occupation is happening at the great temple of conventional British Christianity resonate? "Yeah, it rings a bell with me. From a very early age, whether I liked it or not, I was dragged along to the first Aldermaston march with my parents. You get a big element of that with the church, and I’ve particularly always loved the whole Quaker tradition. Cos I’ve been involved with Druidism – I don’t really believe in it as a religion – I just think it’s synonymous with a lot of things that are universal and worldwide, and particularly with indigenous people. This world is such a beautiful fucking place, and we’re just destroying it."

In terms of contemporaries, Reid is unimpressed, famously, by the Brit-Art crew. "They always said punk was an influence. Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, what a load of old shit that was. It’s Thatcherite art care of Saatchi & Saatchi." He’s not much of a fan of Banksy, either, whose work seems to offer such an obvious continuity to his. "Do you think so? I don’t. Having said that, it’s all part and parcel. It’s all relative to people having a go and kicking back."

As well as his allotment, football remains a major passion. "I support Fulham. When I first went to Fulham with my dad and brother we would meet in the pub at Putney Bridge. If you got there early you’d walk to the ground with the players, after they’d had steak and chips and Guinness. You’re only talking the late 60s! My dad – showing my age here – first went to Fulham collecting for the wounded in WWI. So we’ve supported them for 100 years in our family. When you’ve been bottom of the third division, you have a sense of humour that Manchester United or Liverpool supporters just wouldn’t understand. And it’s taking the piss out of your own players – they get more stick than the opposition." Tracing an unlikely link to the elevated Premiership status of the Craven Cottagers and the implied defeat of global capitalism, he points out. "Now there’s an example that miracles can happen."

Jamie Reid’s exhibition Peace Is Tough, part of the Merge Festival, runs until 20 November at the Bear Pit, Bear Gardens, just behind Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. The St Paul’s Occupation runs for a less predictable period.