The Master Musicians of Joujouka in their village by Maki Kita

"The Masters started playing, slowly got into their vibe and built up and up", says Frank Rynne, long-time manager and producer of The Master Musicians Of Joujouka, describing the wild energy captured on the recently released Live In Paris double album.

"They did three sets: the first was flutes and the drums; the second violin, drums and vocals; the third a full on performance of the Bou Jeloud suite. About 20 minutes into that everyone was on their feet in the hall and by the end we had about 50 to 60 people on the stage. And the only two bands who have ever done that to the Pompidou were Suicide in the late 1970s and the Masters in 2016!"

Imbued with fierce energy and transcendent beauty, the music of Joujouka – a village in the foothills of the Southern Rif mountains in Morocco – is unique. Largely unchanged down the centuries, the Masters use flutes, hand held drums, rhaita pipes, violins and call and response vocals in a traditional trance music that ranges from intensely loud and raucous to meditative. A Sufi sect whose music has long said to have been blessed with the ability to heal, they’ve been performing in the lower Rif for centuries but came to wider countercultural consciousness after the posthumous release in 1971 of Brian Jones Presents The Pipes Of Pan At Joujouka.

Before that they were, of course, visited by many of the leading beat writers. William S Burroughs, Paul Bowles and Brion Gysin all spent time in the village while in the 1970s Timothy Leary and Ornette Coleman (who recorded the brilliant, burning ‘Midnight Sunrise’ with the Masters in 1973) came through. Does it ever frustrate the Masters to be so closely associated with a relatively fleeting cultural movement, though, I wonder?

"To be honest, I get more pissed off with it as a producer/ manager than they do", laughs Rynne. "It’s brought foot traffic through the village but it’s largely irrelevant to them day to day, except as PR. If you’re interested in Burroughs, it’s in his work; if you’re interested in Bowles, it’s in his work but, in a sense, it’s baggage. My approach – my connection to the music – is more akin to Irish folk music. I connect to them on that level: there’s sheep, there’s cattle, there’s goats and there’s drone music."

Rynne has a long, intricate history with the Masters. A Dubliner by birth, who has lived in Paris for many years, he initially sang in early 80s rockabilly band Those Handsome Devils and then fronted Dublin punks The Baby Snakes throughout the latter half of the decade. In 1992 he curated the Here To Go exhibition in the city, exhibiting paintings and artworks from Gysin, Burroughs and Mohammed Hamri.

The late Hamri – often known as ‘The Painter Of Morocco’ – was one of his country’s key countercultural instigators from the 1950s onwards. It was Hamri who was responsible for introducing Gysin, Burroughs and Bowles to the music of the Masters. Gysin, famously, loved their music, stating that it was the sound he wanted to hear for the rest of his life while Bowles found them too loud and intense. Ultimately Hamri helped spread their sound far beyond Joujouka village.

Born in 1932, he was raised in Ksar el Kbir (the nearest town to Joujouka) while his uncle – Sherkin Attar – was one of the bandleaders of the time. Alongside Gysin, Hamri ran the infamous 1001 Nights restaurant in Tangier which quickly became an epicentre for the country’s beat scene, hosting readings and performances from local and international artists alike. Hamri and Gysin employed the Masters as house band at the 1001 Nights while, in later life, Hamri built a house in Joujouka village and in 1975 published a book Tales Of Joujouka – a collection of ancient folklore connected to the Masters.

Adamant that any exhibition featuring himself and Gysin must also rightly include the Masters, Hamri put Rynne in touch with them in 1992, and they came over to Dublin to perform. It was a successful exhibition, but was not without its share of strife for Rynne. The infamous, much discussed, split made itself felt as soon as Rynne made the booking. In brief: there are two bands of Joujouka musicians – The Master Musicians of Joujouka, who are all based in the village and The Master Musicians of Jajouka featuring Bachir Attar, who was based in New York. Details are hazy but the split dates back to the mid 1970s when a group of Joujouka musicians voted to replace Bachir’s father, Hadj Abdeselam El Attar, with Mallim Fudal as band leader. Attar held the opinion that this was illegitimate, claiming that leadership was a ‘hereditary’ position – something disputed by the wider Joujouka lineage. There were also various disputes regarding royalties from the Masters’ mid 1970s recordings.

Panoramic shot of Joujouka by Herman Vanaershot

Asked about the issue of the split today, the usually animated Rynne sounds weary, recalling his fax machine "going crazy" after making the booking in 1992 with various "accusations about the musicians I was working with; and about Hamri". However, the experience galvanised him as a historian and – keeping in touch regularly with Hamri by phone – he eventually travelled to Joujouka in 1994 and lived in the village for a few months.

"Because I’d never seen such a shit storm I needed to go and find out what was going on. In a weird way the only reason I’m still working with them today is because of that shit storm. At the end of the day, it’s simple: you’ve got musicians… and they fall out [laughs]. I traced it back to about 1974 when there was an album called The Primal Energy That Is The Music And Ritual Of Jajouka, Morocco, produced by a guy called Joel Rubiner. Hamri was involved in it and it caused a big argument in the village. Hamri went to California, came back and this guy Hadj was deselected as leader. Eventually, one Joujouka ended up in New York with a record deal and claimed his thing. He’s a musician! Can anyone deny him the right to do what he does? No! Can he deny the right of what the musicians in the village do? No! Music is a subjective thing; music is music. You listen with your ears – if you like the sound of something buy it."

Staying for nine weeks, Rynne got to know the Masters in the village well and, on the trip, recorded the Joujouka Black Eyes LP released by Sub Rosa in 1995. One of the rawest and most intimate of the many Joujouka recordings, Joujouka Black Eyes was something of a baptism by fire for Rynne as a producer, who sat amongst the Masters for days as they were playing, a simple mic positioned in the middle, everything going straight to tape.

"If I could go back to that record I wouldn’t have produced such a potpourri", he tells me. "Black Eyes was taken from around 40 hours of recordings. After four weeks my money ran out. Coming from a punk background I’ve always had a feeling for the anarchic approach and Joujouka Black Eyes is a record I’m proud of, but when I listen to it now I do think that maybe I shouldn’t have edited it so much and maybe I should have let the pieces grow for another 15 minutes each. The first side is flute and drums – the more spiritual Joujouka zone. When they play this music for hours it’s transcendental; trance inducing. When I first went to Joujouka, Hamri would always lie down on his little bed and smoke a pipe of kif and they’d play this stuff which just sends you into another zone. That’s a really elemental thing with Joujouka – the flute music."

Rynne continued to travel back and forth to Joujouka through the 90s, solidifying links with the Masters, recording and, eventually, arranging international bookings as manager. He was even welcomed into the fraternal guild of the Masters by Hamri, who has kept a log book of individual members for many decades, a symbolic honour unheard of for somebody outside the village.

Master Musicians Of Joujouka by Herman Vanaerschot

In centuries past the Masters operated rather like a feudal musicians’ guild whereby, as Rynne describes it, "a rhaita player was worth X, a drummer was worth Y and a trainee was worth Z". Money was divided based on expertise and the musicians’ place in society. When Hamri was working with the Masters in the 1950s he created something more akin to a folkloric association that had around 70 members.

"I was inducted into that membership in 1994", Rynne recalls. "I was number 63. Even now in the village, sometimes musicians I haven’t seen for years will come up to play and show me their card and I’ll take out my card. It perhaps doesn’t have the same resonance today as it once did, but there is fraternity, for sure; all the older Masters who played with Brian Jones and played on those albums in the 1970s, they were all members of that fraternal guild. I don’t think it gives me any rights though – I’ve no sheep in the village! I’ve worked with these musicians for 29 years. We know each other’s families. They know my kid, I’ve known their kids since they were born but it isn’t Masonic; we’re not climbing up ladders or anything. It’s about affirmation."

From a production standpoint, Joujouka Black Eyes was an in situ field recording assembled from numerous loose jams and sessions held over a period of weeks. By way of comparison, Live In Paris is a very different proposition, and much tighter focussed.

Recorded in 2016 at the Pompidou Centre, Live In Paris captures all facets of the Joujouka sound across a double LP. The first focusses on flutes and drums and, in particular, the beautiful mountain violin of Ahmad Talha, who plays his instrument upright, haunting melodies snaking up and over the mix. Most striking of all, however, is the Bou Jeloud suite on the second record. The sound of the Masters at their loudest, weightiest and most ferociously untethered, Bou Jeloud is the wildest music in the Masters repertoire.

Generally performed at the annual Bou Jeloud festivities in the village, the ritual dates back to the sixteenth century when Bou Jeloud (a half man/half goat Pan like figure) was said to have appeared to a local shepherd near a cave outside the village to bestow fertility and harvest bounty on the village. The occasion is marked each year in June with extended night long dancing and feasting while a chosen villager – sewn into bloody, freshly slaughtered goat skins and wearing a huge mask – dresses up as Bou Jeloud and frolics, dances and thrashes assembled dancers with olive branches in front of vast bonfires.

The Live In Paris recording is a particularly visceral rendering of the suite – indeed, the first time it’s been captured in its entirety. Was it challenging performing this specific music outside of the village, I wonder? Did the vibe transfer?

"Bou Jeloud is a transferable ceremony", explains Rynne. "This means as long as you have Bou Jeloud and the music, it can transfer. Even in their own region, if people want the Masters to come to another village and do Bou Jeloud they’ll do it, and that goes back centuries. Even in Joujouka there is no specific site where Bou Jeloud will be performed. I’ve seen it performed in different parts of the village over the years and in various different ways. I’ve been working with the Masters for over 30 years and in that time I’ve seen Bou Jeloud performed long and short. I’ve seen it last for two hours and I’ve seen it last for nine hours."

Capturing the shrieking drone of the lead rhaita pipes and balancing that with the frenetic handheld drums (the drummers form a circle for Bou Jeloud) is no mean feat, however.

Over decades of producing the Masters, Rynne quickly understood that balance was the key to everything. Too much rhaita, or too much focus on the drums, and the power of the music is dampened beyond repair. He enthusiastically describes the scope for structured improvisation, and communication, as essential in the way that the music works.

In essence, the Masters are led by two people: the lead rhaita player and the lead drummer. "And they signal each other", explains Rynne. "And they’re like a machine. If you’ve been listening to Joujouka for years you get to know those signals. For example, if the lead drummer does three beats – doof doof doof – that means that they’re moving to the next section. Or if the lead rhaita does a pigeon call that means that they’re flipping it back round again. Also, they can feel where the audience are at in terms of exhaustion."

While a certain amount of looseness and improvisation is intrinsic to the vibe, the structure of the Masters is generally staid. On the rhaita, a bank of musicians play drone and melody. Rynne describes this as "the rhythm guitar, essentially". Then you have a couple of lead pipers transcending the melody. The vibe for Bou Jeloud on the night in Paris was "right up there with the many times I’ve witnessed it", he explains.

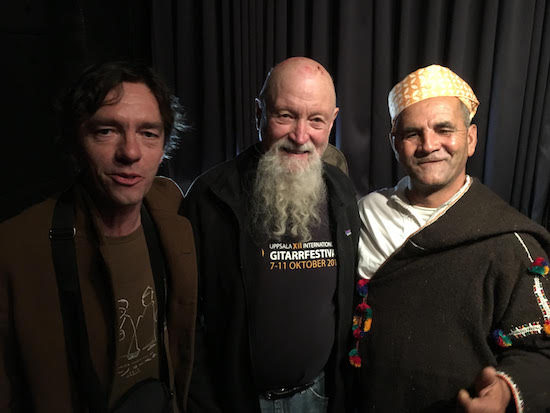

Frank Rynne, Terry Riley and Ahmed Attar in Tokyo 2017 courtesy of Frank Rynne

As the band got ready to perform the suite, they stood up and formed the customary circle with the drummers. Rynne recalled hearing the "snort" of the dancer and got ready with a boom mic over the musicians and audience. "There was no point in close mic-ing the rhaitas. It’s one of the very hardest things to record, Bou Jeloud with rhaita. Over the years I’ve tried to do it with different methods, but I gave up in the village because very rarely do you have the balance. But I think we did it the best that it’s been done so far."

Predicated on ceaseless, ever building motion, the drone of the pipes build to fever pitch while the drums pound away in circular motion; the wild grunts and snorts of Bou Jeloud are captured, as are the frequent whoops of the crowd. Live In Paris also captures the last recorded performance by the late Master Abdselam Boukhzar, who sadly died in 2019. Ultimately, though, this is the first time that the weight – not to mention the searing, face-melting volume of the Masters – has been captured, as Rynne concludes: "What was always missing on Joujouka records was the bottom end. At the top end you have the solos in the flute and rhaita and they are the keys to the music. So on the first two sides we were able to sort that out, saying, ‘That’s the solo, that needs to be high and loud’, but on the Bou Jeloud side it was all about EQ-ing so that we could sit it all in the perfect place, as you’d hear it if you were watching in the village. And that’s what we did, as close as you can do with this type of music, because when you stand in front of the Masters they self-mix in terms of where they place themselves in front or behind the drummers… but just try and record that [laughs]. We did several days of mastering, not so much changing anything but identifying the relevant frequencies to the engineers, the pivotal moments and that’s why Bou Jeloud sounds fucking amazing. It’s as loud as a death metal band. It’s been 14 years since I’ve done a record and I think on this I did what I set out to achieve which was to bring the power of the music out. Inshallah, it’s done."