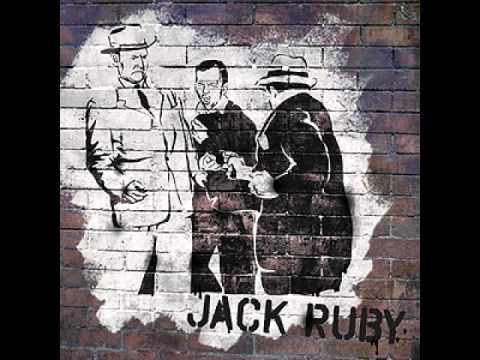

Photograph courtesy of Stephen Barth

Jack Ruby is the name of the man who shot Lee Harvey Oswald, who in turn assassinated JFK in 1963.

Jack Ruby is also the collective name adopted ten years later by a group of people more recently credited as being "the most influential punk band from New York City that no one ever knew about".

It’s an intriguing strapline, an endorsement from none other than Thurston Moore whose band, Sonic Youth, grew out of the New York no wave scene in the early 80s. Jack Ruby were indeed an enigma, as close to an urban myth as you might get; their very existence the subject of rumour and speculation among the NYC music community until their only recent rediscovery. But much as this quote serves as a tasty lead into the liner notes of Hit And Run, a new Jack Ruby retrospective on Saint Cecilia Knows, Moore’s description is also inaccurate.

For one, Jack Ruby weren’t a conventional band, rather a loose procession of drifters, literary nerds, surf music enthusiasts and electronics whizz-kids who, for whatever reason, worked in obscurity until their disbandment (a single through Epic was planned but plans fell through). This eventual parting of ways took place in 1977, meaning the majority of Jack Ruby’s minimal output preceded punk by quite a few years. And while the ratchet-y guitars and snarling vocals on lead track ‘Hit And Run’ might suggest the dysfunctional proto-punk of The Stooges, the truth behind the music is even more obfuscated.

On the surface Jack Ruby could be lumped in with any number of bands who made punk music before the fact. It would be tempting to put them in the same box as Death, the recently-disinterred black 70s rockers whose confrontational sound anticipated punk music but also failed to gain recognition until decades later. There is also a notable Velvets influence in guitarist Chris Gray’s squalling freeform approach, said to be informed by the song ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’ from White Light/White Heat.

Even so, the supposed ‘punk-rockness’ of Jack Ruby is felt only spectrally, the songs themselves buried under layers of impenetrable noise. This isn’t just guitar feedback or recording hiss (of which there is plenty), but clanking and smashing sounds, squealing sine waves; a piercing dentist’s drill on ‘Hit And Run’ which threatens to drown out vocalist Robin Hall and the rest of the band entirely. We’re left staring at the ghosts in TV static, an impression of what might have once been a band if you look hard enough.

These curious effects came courtesy of the Serge, a subtractive synthesizer with sampling capabilities which multi-instrumentalist Randy Cohen helped to develop during his time at the California Institute of Arts (CalArts). Alongside the bizarre punk-concrète of ‘Mayonnaise’, the new collection features a number of tracks on the second disc recorded by Cohen with help from violist Boris Policeband and other members in early 1974. These tracks bear closer resemblance to experimental electronic music and ambient, pre-dating Brian Eno’s own Discreet Music album by a matter of months.

Eno’s fingers, as ever, were in many pies at this time, and it would be he who would come to curate the iconic ‘No New York’ compilation in 1978, which showcased four of the most cutting-edge bands of the no wave scene – D.N.A., Mars, James Chance’s Contortions and Lydia Lunch’s Teenage Jesus And The Jerks. The latter two bands were directly associated and influenced by Jack Ruby: bassist George Scott III played in the band before finding success in the Contortions; Lunch too had been part of the Jack Ruby entourage when she first came to NYC and most certainly attended the communal jam sessions/gatherings held by the band.

Thanks to the recovery of the original master tapes, we can now hear Jack Ruby for real. This mysterious band, whose music and history is riddled with non-sequiturs, really did exist. In an e-mail conversation, I caught up with Robin Hall (vocals) and Randy Cohen (Serge synth, drums) about their time with the band and how Jack Ruby may well be the missing link in the punk rock chain.

You’ve been hailed as "the most influential punk band from New York City that no-one ever knew about". How does this description strike you? Is it fair?

Robin Hall: The second part is certainly true. I’m not sure how influential you can be if no one heard you. I believe we influenced the people who did hear us and were open to what we were doing.

Randy Cohen: The second part is certainly true. We managed to preserve the fragile flower of our total obscurity. "Influential" is harder to gauge. As you mention below, some of what we were doing would later be done by other bands, but whether they got these ideas from us – directly or indirectly – is tough to trace. It’s like trying to track a viral outbreak back to its source. So, yeah, this seems fair in the musicological sense, but disheartening in a broader sense of fairness. It’s hard not to wonder what might have happened had Epic actually released these tracks. As things are now, my friends refer to the new CD as my posthumous success.

Jack Ruby, as a band, were witnessed by a very select few people in their time, but it also seems you kept good company with the likes of Tom Verlaine, James Chance and Lydia Lunch. How much of an impact do you think you had on these figures and their bands?

RH: I believe we had an impact on Lydia and James, and through them the various members of bands they were in – (think of all the great musicians that played with them!) Maybe a small influence as a result of what some of us did individually after Jack Ruby ended. George Scott [bassist] had a big influence, and Chris Gray [guitarist] influenced him a great deal.

RC: Chris and Robin kept good company; I barely left my apartment. But sure, this does argue for Jack Ruby being influential indirectly, by whispering dark thoughts into the ears of people who’d later apply them in their own work, rather than our reaching listeners directly.

Jack Ruby came about some time before the punk scene officially exploded. Do you feel you were ahead of your time? What did you think when punk finally did break? What were your thoughts on punk rock and its late-70s New York offshoot, no wave?

RH: Personally, and I think Randy and Chris would agree, we felt we were ahead of our time. When we came to NYC, the Dolls were famous. Anything else interesting was extremely under the radar. Patti Smith had just put together a band with Lenny Kaye. I saw Television at what I believe was their first gig, with [Richard] Hell still in the band. It was pre-punk time (although I wrote a song at the time called ‘Existential Punk’, so the word was in the air). I loved punk and I loved no wave. I actually think the best period for music in New York was the late 70s – I guess it was post punk. Not only the no wave bands (including Bush Tetras) but great pop bands like The Bongos, The Individuals and The dB’s. And other, less classifiable bands like Human Switchboard, Polyrock, Ballistic Kisses, The Fleshtones. There wasn’t a huge differentiation between bands because of the type of music. The Bongos would be on a bill with 8-Eyed Spy. Everyone was friends. I remember meeting Peter Holsapple [The dB’s] when he was working in a record store with George Scott.

RC: I do feel we were ahead of our time, which is as much a guarantee of failure as being behind your time. "The readiness is all", as Shakespeare said, or maybe it was Phil Spector – two guys who really knew the tone of their own times. When the punk scene started gaining an audience, I was an enthusiastic fan – these were some terrific bands – which did not inhibit my being bitter and resentful and jealous.

Were you disappointed that Jack Ruby remained obscure? Did you have designs on making it big? In an alternate reality, do you think Jack Ruby could have had the same kind of commercial recognition as, say, Pere Ubu or Television?

RH: Yes we had designs on making it big, but on our terms. Our goal was the same as any pop band at the time: have hit records, play American Bandstand, play a charity basketball game against the New York Dolls at halftime during a Knicks game at Madison Square Garden. It was NYC in the 1970s – disappointment was a way of life. Jack Ruby’s lack of success was, for me, more frustrating than disappointing. I think we were ahead of our time, but I don’t think we did ourselves any favours by not playing out. Evidenced by the small but intense crowds who would show up at our rehearsals, I think we could have built a following.

RC: We were as ambitious as every other swaggering twenty two-year-old in every other band, and yes, we truly thought we’d recorded what would – should – become a hit single. My deranged vanity aside, I like your parallel to the bands you mentioned. We might well have had that sort of modest success, a minority taste perhaps, but the people who enjoyed it really enjoyed it. Nearly every band ends short of glory (nearly every human enterprise, for that matter). But this one was more disappointing than most because I thought we were onto something and Epic’s interest had brought us so close. I was disappointed but not depressed that we didn’t go further. But then we all got on with our lives. Before these tapes reappeared it had been decades since I’d even thought about them. It’s delightfully disorienting to see them come out now, a mere 40 years after the recording sessions. One lesson for me: if you work hard, you can achieve anything you strive for, but it will be too late.

Could you tell us more about the ambient tracks on the second disc of the anthology? How do they fit in with the rest of what Jack Ruby was doing? Were you aware or interested in Brian Eno and his own ambient work?

RH: These are questions for Randy. I would say we were all aware of Eno and the German bands. But a lot of that, I believe was influenced by Randy and Chris’s years at Albany State and then Randy’s work and studies at CalArts. The beauty and power for me is the conceptual artistry. Those tracks represent a musical point of view as radical in their own way as Jack Ruby’s were.

RC: In the alternate universe where Jack Ruby became huge, those tracks would have been on my solo album and the liner notes would have said catty things about how the other guys in the band were thwarting me. One of the things I liked about the band was the way our tastes overlapped but were not identical. What we did could only have been done together. These solo tracks embody some of what I brought to Jack Ruby, emphasising my particular interests. I was a fan of Roxy Music but didn’t pay any attention to Brian Eno’s solo work. No, wait, I do remember later enjoying something called ‘The Murmur Of Worms’. Is that the right title?

What impressed me most about the new anthology is how much of it seemed to pre-date music that came out relatively recently. Along with The Velvets, The Stooges, the no wave bands, I’m also hearing elements that would later be used by acts in the Brooklyn noise scene – bands like Wolf Eyes and Black Dice. ‘Mayonnaise’ could have been an outtake from a Liars album for example. Is this a matter of influence? Or is it simply a matter of people ‘catching up’?

RH: Even now, I sometimes listen to Jack Ruby and I think "no one will get this". Other times, I hear it and it seems to fit perfectly into one genre or another. No wave, post punk, Sonic Youth, Nirvana, Beastie Boys all did stuff that helps make it more understandable to an audience.

RC: Some ideas seem almost inevitable: even if their credited inventor had never been born, the circumstances in the world would have led to someone else, or several someones, to devise those ideas. That’s my current thinking about Jack Ruby. If we’d never existed, the music scene today would be just what it is. But then, I have a bleak view of life.

What happened to the members of Jack Ruby? Did you continue to be involved in music? If so, are you doing anything now? Did you ever meet Boris again?

RC: Boris died a few years ago; Chris died a few weeks ago. I abandoned music entirely by around 1976, deciding that I wasn’t very talented. I began writing prose, mostly humour, first for magazines then for television (David Letterman, Michael Moore, and some other shows). From 1999-2011 I wrote a column called The Ethicist for the New York Times. Now I’m working on a small public radio show called Person Place Thing. You can hear some episodes at its website.

RH: I fronted a band from ’78-’80 called W-2, which had a little success in the Tier 3/Hurrah scene that grew up around English post punk and the no wave bands. I played with a guitar player named Russell Berke and a series of drummers (including James Sclavunos and Dougie Bowne). We opened for Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark and Monochrome Set. Unfortunately we were as reckless as Jack Ruby and broke up before we could really develop a personality. Now I play guitar for my kids and create mixes on my computer.

George’s career after Jack Ruby is well known. Chris moved back to Albany and was in at least one other band, although I don’t know its name. Randy channeled his creativity into other avenues. Ask him about his comic book. Randy and I had lunch yesterday. One of the delights of this whole experience has been reconnecting with him. I used to see Boris quite a lot after he left Jack Ruby. He would come over to my apartment and watch TV (as only Boris could watch TV). And I saw him a lot at the Mudd Club, where we both hung out. But he passed away in the early 2000s. Unfortunately, Chris, the soul of Jack Ruby, passed away two weeks ago. I hope that this release will bring him some of the recognition he really really deserves. He was truly an arresting guitar player, as well as a first class conceptual artist.

Hit And Run is out now on Saint Cecilia Knows; head to the label’s website to get hold of a copy