Over the last couple of years, heavy metal has undergone another of its periodic rehabilitations. For kids today, old school heroes Iron Maiden and Judas Priest are viable t-shirt options, and everywhere you look there’s a lank-haired teenager flashing the devil horns. But the current renaissance isn’t based on any sense of renewal in the music itself; it’s all about the trappings – the denim, the leather, the logos etc. Metal may be doing just dandy in terms of visibility and sales, but it still isn’t being taken seriously. It’s being patronised. And understandably: the genre, since it congealed into a marketable set of signifiers roughly circa 1977-1981, has continually exposed – if not championed – itself as a world of dumbness, where sexism, racism and homophobia are common, and any challenge to these is viewed with derision. It’d be fallacious to suggest that all metalheads are right-wing bigots, but the rhetoric commonly adopted in the genre makes it a potentially hostile world for those who would oppose bigotry and ignorance. This situation certainly hasn’t been helped by the frequent lapses into ideological idiocy that have come to characterise Norwegian Black Metal, and few other musical genres have a entire branch dedicated to the dissemination of National Socialist politics (the neatly abbreviated NSBM).

But on the fringes of the genre, evolution is taking place, sonically at least. It could be considered the continuation of a strain of grassroots avant garde extremity beginning with outward-thinking bands such as Canada’s Voivod and Switzerland’s Celtic Frost in the 80s (themselves taking the lead from punk metal hybrids like Killing Joke and Amebix) and continuing through the likes of Godflesh and Napalm Death, before the glorious emergence of bands such as Sunn O))) and Boris, bands unafraid to blend their love of The Riff with influences previously only recognisable to readers of The Wire.

Elements of jazz, electronic music, classical, drone and noise are finding their way into the mix, producing a variegated music that may not be easy to market – although Southern Lord have succeeded partly by crafting a new marketing aesthetic out of well-worn cliché – but which is looking increasingly like the future of the genre, no matter how desperately we cling to the beloved image of Eddie The Head.

The real future of metal – by that I mean its artistic, rather than commercial, future – lies not with bands slavishly replicating the speedfreak innovations of early Metallica or smashing beercans on their heads in tribute to the reverse sleeve of Slayer’s Reign In Blood. It lies with sonically erudite artists taking inspiration from disparate sources and daring to appeal to listeners familiar with a broad spectrum of musics. The established metal-orientated labels may prefer their demographic to stay dumbly loyal, sucking up whatever fifth generation bullshit they see fit to peddle (lately it’s been an endless dribble of metalcore – for the uninitiated, a dead-end, formulaic blend of hardcore and metal) but small labels such as Crucial Blast, Profound Lore, Battle Kommand, 20 Buck Spin and Hydra Head are presenting the metal masses with cutting edge music which is viciously uncompromising, blissfully untainted by commercial concerns and committed to the advancement of metal as an artform. These labels and bands often find themselves tagged as proponents of ‘hipster metal’, but you don’t need to worry about that. It doesn’t actually mean anything.

The emergence of a loose subgenre some are calling ‘metalgaze’ is a part of this evolution. Ever since the release of My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless in 1991, indie rock has struggled to contain its influence, at best chucking out feeble replicas of that album’s torrid reinvention of the guitar, at worst ignoring it completely. The album has proven a more effective influence on contemporary electronic music, with artists such as Peter Rehberg and Fennesz offering a digitised angle on the bliss-horror equation.

But lately, and coinciding with MBV’s reformation for a number of high-profile live performances, the six-string abstraction of Loveless has impacted on various strains of metal, from black to doom to drone (interestingly Kevin Shields once confessed to a period in which he attempted to incorporate death metal licks into his playing). MBV are currently being reclaimed as extreme music, and the Shoegaze genre they birthed is proving fertile ground.

Canadian duo Nadja have taken this particular ball and, well, dawdled with it, though impressively, investing their music’s slow, sensual crawl with a textural awareness clearly derived from the ‘glide-guitar’ experiments of Shields. Their ever-expanding catalogue is replete with epic, throbbing, monumentally psychedelic works; Desire In Emptiness, their recent album for Crucial Blast is a good introduction. Justin Broadrick’s post-Godflesh vehicle, Jesu, takes the intimidating enormity of his previous outfit and loads it with the weight of the heaviest heart, exposing the primal absence at metal’s core. And Black Metal, which has always proven intriguing for those attracted to acid-fuzz guitar, has recently thrown up Alcest, Wolves In The Throne Room, Trancelike Void, Coldworld, Brown Jenkins, Wrath Of The Weak, Caina, Altar Of Plagues and Darkspace among others, deviants and dissidents all, deconstructing and distending metal’s source material, The Riff, beyond the self-imposed restrictions of the genre.

Somewhere in the midst of all this we find Pyramids, a Texan collective heavily influenced by French experimental Black Metal duo Blut Aus Nord (who contribute a remix to the bonus disc of their self-titled debut for Hydra Head). Their music also exhibits a dub-me-crazy fondness for extreme reverb, recalling lost 80s feedbackers AR Kane. Kevin Shields once discussed the modus operandi of MBV as "taking all the guts out" of rock, leaving "the remnants, the outline"; Pyramids perform a similar act of creative evisceration on Black Metal.

I ask Pyramids member r if he thinks the recent tendency toward textural exploration marks an evolutionary leap for the genre.

"Metal fans often lift their heads in awe of little things that are said to be an experimental move or departure from classification," he shrugs, "when in reality these things are usually not new concepts, and have been done, probably better then than they’re being done now. That raises the question of whether we are actually being experimental and progressing, or just adding old ideas to our music, only not as good, and watching Metal fans stand in awe of these things."

Some readers might recall that the same schism arose in mainstream circles when Radiohead released Kid A in 2000; while fans of The Bends and OK, Computer might have considered that album a radical reinvention, those familiar with the output of labels such as Warp, Mego and Raster Noton viewed its electronically-augmented post-rock as half-baked, even passé. But however well-established the individual elements are in their own worlds, the recent trend for combining metal’s sense of threat with the immersive idyll of shoegaze is undeniable, and only one aspect of the ongoing cross-pollination taking place in extreme music. For his part, r views the ‘metalgaze’ movement as less entropic than cyclical.

"I think both categories lend themselves to each other naturally. Both are very texture-orientated and lush," he says. "Sooner or later the noise gets so dense that it is pretty again. The white noise aesthetic in many Black Metal recordings is so lush at times it is relaxing, and that is where the evolution of the same textures found in bands like MBV and Slowdive start to be found again. It’s a lot like watching music complete a full circle."

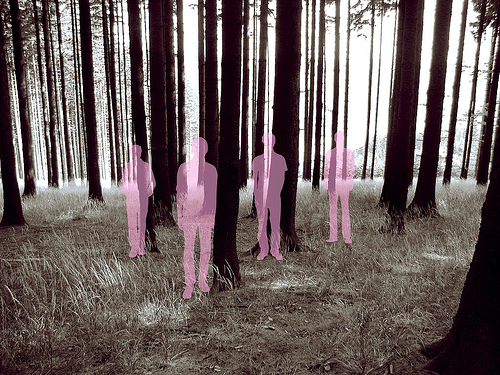

To see more of Koen Jacobs’ excellent photography visit his flickr site.