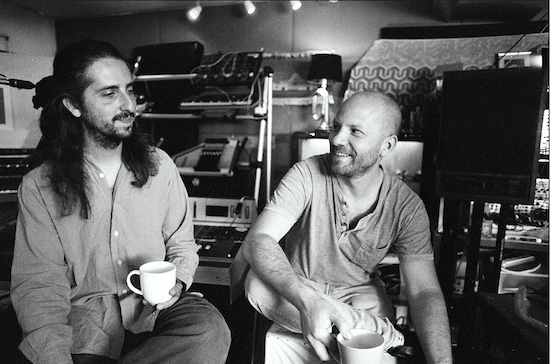

Music writers. Who needs ’em? We recently had the opportunity to get Wacław Zimpel and James Holden together and left them to have a conversation about their individual practice without any interference. Wacław Zimpel was born in Poznan, Poland in 1983 and is, primarily a concert/jazz clarinetist. As well as solo material he has collaborated with Jakub Ziolek and Saagara. James Holden was born in Exeter in 1979 and has become known for his work with modular synthesis in a progressive techno context. He set up the Border Community label, has remixed both Madonna and Britney Spears and recently formed the band The Animal Spirits.

The pair collaborated on the Long Weekend EP which is out now on Border Community.

James Holden: I read somewhere that your first love was Queen? Me too, so to me it makes perfect sense that we’ve ended up meeting musically, even though we took different routes to get where we are. I think we meet on the idea of trance music, hypnotic subtly changing magick music, that kind of thing, and I’m curious when that started to be something you thought about? Earlier in your career when you were playing free jazz did that feel like trance?

Wacław Zimpel: I had this pirate cassette which the Polish market was full of in the 90s with the best of Queen. I loved this music and I still do. I didn’t know that you were a fan too!

I am not sure when I first realised that what I like to listen to and play is a form of trance music. I think that the first form of this music which attracted my attention, was folk music from the Polish mountains. But it was sort of a guilty pleasure, as teachers at musical school back than used to underestimate folk as something that wasn’t very good as compared to classical music. Later on I discovered old blues records when I was 14 or 15. I used to play old songs of Howling Wolf and Leadbelly on guitar and harmonica and it was first time I think I really started playing trance music. But I didn’t see it that way at the time. Soon after I discovered blues for myself I started playing clarinet and learning jazz standards. And I preferred the compositions with hypnotic rhythms and one tonal centre like music of Alice Coltrane much more.

Very often I felt this magic while playing free jazz, but mostly it was when I was playing repetitive rhythms connected somehow with one tonal centre. But while playing more abstract forms of free jazz concentrated more on sound itself, that the way I listen takes me to this other state of mind as well. And how was it for you? And what is trance for you. How do you define it?

JH: This is funny, discovering new things we have in common. Yeah I still love Queen too. For me, learning piano and violin as a child, there were two things I really liked: I had a book of Scottish Ceilidh music that was the best thing I played on the violin (and my teacher similarly thought was a waste of time) and on the piano I discovered early that hammering out simple patterns – also blues! or my own sequences of chords – for hours was way more interesting than practising classical repertoire. I think it was only later (when I began trying to work out why electronic music had this power to make me feel magic things) that I realised what I was enjoying with these was getting into a trance state.

I’ve got a million definitions for trance – but the first sign for me is when you start hearing inside the sound, or outside linear time – notes aren’t just a note in a place in a sequence but exist in relation to all the previous and future versions of themselves. Does that match your definition? And did you find your way to trance on your own, or did you meet people along the way who helped? I’m also curious what the Polish mountain folk music sounds like?

WZ: Polish folk music from the mountains is great, but there are much more amazing traditions in Poland which are actually dealing with idea of trance much more. I am thinking now about wedding music and dances like mazurka or oberek. While dancing them you whirl in couples for a very long time to repetitive structures. Really amazing trance experience. And the timing of this music is really something else. It is not possible to notate this sense of timing which is very much connected to the way people dance.

But coming back to trance itself, to me it is also the state of mind in which time bends. To me one of the ways of getting to this state of mind is via repetition of a pattern. After many repetitions I stop thinking about this and I become equally listener and player. Eventually I have the feeling that I am disappearing. I think I first discovered this consciously after a concert of one Polish blues player Jan “Kyks” Skrzek when I was 15, I think. He played his blues songs in Silesian dialect and for an encore he played an amazing piece for piano solo which I remember till now. It was just C – G – C – G in the left hand in quarter notes and repetitive patterns in pentatonic scale in the right hand. It was very simple so I could play it myself at home and I did, thousands of times. I think that this is how I became trance devotee.

Later I discovered that to get there you don’t have to repeat patterns. What I mentioned before, the way of listening can also take us there. I have never met Pauline Oliveros, but I follow her concept of deep listening. I found out that when I concentrate long enough on one source of sound and then on the next one and the next one after that, listening to them simultaneously, I also have the feeling of disappearing. And this is the state of mind when music happens beyond decision.

I really had this feeling when we were recording ‘Sunday’. It was a really magic moment, right? I have no idea where this music came from… I also wanted to ask you, why trance is so important to you? What this state of mind gives you?

JH: Yeah recording ‘Sunday’ was the magic feeling wasn’t it? I remember feeling like I didn’t really know the chord sequence properly but I knew where to go anyway.

It connects back to what you mentioned about whirling dances – somehow when you dance like that, or run down a hill, or play music that you haven’t written yet – you have this feeling of being guided by something other than yourself. I love that feeling, partly because it’s a bit superhuman, you’re doing something you didn’t think you could, but also partly because it’s an escape from being you. I think that’s a part of why I liked trance states – before I knew the concept of meditating it was a way to get into a calm space where I wasn’t worrying about life or whether what I was playing was good or not good or whatever.

WZ: I totally understand what you mean about improvisation in a trance state; how you do stuff you wouldn’t imagine in normal life. For example it happened so many times to me that while playing a free improv concert with two or three other horns we all started with the same note. Also the process of improvising new forms together with other musicians is difficult to describe. It is just happening if you are open for that. But I am also wondering if getting to those trance states of mind makes us superhuman or simply more human? Maybe we just forgot about our natural potential?

I think that playing music or some forms of meditation might bring us closer to it. What I love in playing music, especially if it is an improvisation, is that it is meditation in action. So while doing this we are very much grounded, connected to our instrument and at the same time our mind is somewhere else, where ideas come from.

JH: You also mentioned about un-notate-able timings, which reminded me of Gnawa music. I remember sitting with Sam [Shepherd, Floating Points] trying to work out how the swing worked on a Gnawa rhythm part and having to use the computer to help us – recording a bit and seeing where things lined up with the grid. You could sort of describe the patterns as 12/8, or sometimes as swung 16ths, but really classical (and computer-grid) notation falls down trying to describe this music too, because it comes from the body of the people playing it. I learnt so much from that trip – particularly about trance – I started to understand it as a universal thing – a parallel evolution so that a 62-year-old Gnawa Maalem plays in the same structures and forms, and pushes the same mental buttons, as kids making techno in Europe. It’s a funny coincidence that around the same time I met Mahmoud Guinia you were playing with his brother Mokhtar. How was that?

WZ: This is really crazy, that we have met Guinia family at the same time! Playing with Mokhtar felt to me like we had always been playing together. It felt like I had found the source of blues and music in general in his tradition and in his playing. Floating on clarinet on top of those hypnotic grooves is something I could have done forever!

I have never been part of a Lila derdeba ritual though. You have been part of one, right? I really would love to experience it one day. I love the concept of Gnawa philosophy that music is for people to get rid of bad influences. I want to play this kind of music myself.

JH: So, thinking about the Gnawa Lila I went to has given me my next question – I wondered have you ever been to a techno/trance free party or squat party or illegal rave or anything like that? The reason I ask is because that’s the experience that the Lila was most similar to.

WZ: When I was a kid I was rather going for jazz jam sessions than raves. But I understand what you mean. But somehow what is difficult for me is lack of intimacy when crowd is too big. Lilla feels more cozy and safe.

JH: I feel lucky to have been. Houssam and his band invited me after a show we did in Marrakesh and we drove up into the Atlas mountains to Moulay Brahim where Houssam was one of several Maalems playing. We arrived around 2am and it was packed. It was in the small courtyard of a house with balconies on two floors above. There were people sitting or standing on every inch of floor – all generations, from children to the very old. People would move to the middle and begin to dance – simple, repetitive shuffling steps, nothing showy – and then almost invariably go into their own trance states, some joining in the music, some crying or shouting, some collapsing unconscious and waking in the arms of a family member minutes later. It was very serious, but also a warm, welcoming place. Of course on the surface it was very different to an illegal rave (no one sacrificed any goats when I was dancing in the woods to trance when I was a kid!) but the sense of community, of openness, of care, and of a group of people with a kind of common purpose in finding a different state of mind was identical. Is now a good time to ask about Saagara? The rhythms your bandmates in that play remind me of Gnawa in their intensity.

WZ: I hope we are gonna play together forever with Saagara – I love this band. And I think about Indian rhythms every day because it is such an amazing tradition. And yes, I agree that Saagara, especially now, has a lot in common with Gnawa and other African trance traditions. With Saagara we are concentrating mostly on the groove. Percussionists Giridhar Udupa, Aggu Baba and K Raja are real masters of the rhythm. Hearing them bringing total virtuosity and complexity of accents to repetitive grooves is something I really love about this group. It is very unique how they achieve this I think. But we were working on the collaboration for quite a long time. It wasn’t an instant thing for us to find our style and bridge between our different experiences. I think that playing with sequences, loops and arpeggios helped us to find our language.

The Indian approach to the rhythm is very intellectual. Every rhythm is codified and since the very beginning of their education Indian classical musicians understand exactly where they are in relation to the beat and tala – rhythm cycle. Within the years they are making those structures more and more complex which is really hard to understand for western musicians.

And however those rhythms can be also very hypnotic I think that trance, meditative experiences comes from a different angle here. In traditional Carnatic concerts very often ghatam or khanjira players have to repeat on the spot something which the mridagam player proposed on stage never hearing this before. And most of the time these are extremely difficult things to play. Even though those classical Indian virtuosos have a lot of education and knowledge, still it requires the highest amount of concentration for them to be able to do this. And I think that here comes the other state of mind – from extreme concentration of what is happening on stage.

JH: You mention complexity and I find it interesting that both Carnatic & Hindustani classical are very hypnotic but require a deep level of concentration to ‘hold on’ to the repeating patterns and structures that run under them. In techno (and in krautrock) some of the most common patterns are around a 2 beat long cycle – if you make a 4 beat rhythm pattern it already seems to have diminished the power of it. But I’ve experienced this thing – first you’re trying hard, consciously, counting, recognising the shape of the pattern, seeing what the players are doing with it, then after a few minutes all of that is as internalised as breathing. I remember trying to explain this to a few people when Camilo Tirado first started sharing his knowledge of Hindustani classical with me and being told I’m trying too hard, over-intellectualising, that I should just feel the music and kind of not being sure whether I agreed or not. Now I see that the concentrated conscious thought is just a bridge into a different kind of trance state though. Does John Coltrane manage this too? Thinking about how in Indian music it’s modal, you can listen to his music like that, or you can follow all the insane Giant-Steps-y changes underpinning his soloing.

WZ: I think that concentration in playing jazz is a bit similar to the Indian Classical way of improvisation. To me it is more clear when we take some jazz standard tunes with chord changes. To play these songs you need to follow the form. So on the one hand you need to be creative and play yourself and at the same time you need to know what note you play on which chord. So it requires a lot of concentration and flow at the same time. To me what Coltrane does in modal pieces is more like ebb and flow. He goes away from the tonal centre and comes back. Like tension and release.

JH: We talked earlier about kind of ego-death experiences, of being unaware of how you are doing something, or feeling like it’s not you. This is really explicit in Hindustani classical music. Artists talk of the music already being there and the performers just finding it, but also it reminds me of something you told me once about pre-concert nerves. This is something that at various times I’ve struggled with but the thing you told me your bandmate said almost cured it totally. I think you should repeat it here because it’s some of the best music advice I’ve received in my life but also underlines this kind of attitude to ego and authorship.

WZ: The advice you mentioned comes from my dear brother Aggu [Bharghava Halambi] the khanjira player from Saagara and great spirit! I have learned so much from him. Once after a concert when I was pissed at myself that I didn’t deliver the way I had wanted, Aggu told me, ‘You will never be less than you are and you will never be more than you are, so why to be nervous?’ True wisdom.

I wanted to ask you how do you shift from playing to mixing. To me it comes natural to command long forms while playing, but then to control them in the mix and making decisions about what should be more important than the other, is really difficult. There really is a different perspective of time at play. While playing you are in the moment, while mixing you observe a timeline which has already happened. What kind of experience is it for you?

JH: In a way with mixing it’s easier. You listen to the whole thing a few times, try to understand it, try some things out, then kind of work backwards. You know where it’s going now, so you can make all the little changes that lead to that point. People are like frogs in pots of water. If you make small changes they don’t notice, so if you know the big moment is going to be the introduction of heavy bass, you can slowly reduce the bass more and more for the minute preceding that then it seems bigger when it hits. But the balance/ sense of flow I’ve only ever managed to get good by getting into a tranced-out state and going over it dozens of times making little changes.

To be honest having spent so much time working like this – with an arrange page you can go back and forwards on – playing long-form music was hard for me at first. I found it took time and practice so that I could make these long arcs without thinking – otherwise I’d finish and realise only seven minutes had passed. When you play a long performance are you aware of where you’re going? Does a plan form? Or do you just exist in the moment entirely?

WZ: I think it depends a lot on the kind of music I play. When I play free improv I never plan anything and I have no idea where it will go. It goes where it goes and I just follow. When I want to have more control on harmony and rhythms I plan some patterns, structures or some methods which are the basis of whole piece. I think that in both cases my relation with time is more or less the same – I stop when I feel it is enough. But anyway playing long form feels very natural to me, as I have done this for a long time, but mixing it is a different story. To me it is super difficult. I have no problem with improvising an hour of music, but listening back and deciding what is important and what isn’t, is something like total madness to me. Somehow I trust myself more when I am improvising.

Long Weekend is out now on Border Community and Massive Oscillations is out now on Ongehoord