Music writers. Who needs ’em? We recently had the opportunity to get heroic cult indie rocker Stephen Pastel and always impressively scrubbed up writer David Keenan together. We left the Pastels mainstay and the musician turned champion of underground music turned gifted novelist to have a conversation about their individual and joint practice, without any interference from us.

Keenan has spun the poacher gamekeeper roulette wheel with such enthusiastic verve in the past that it perhaps should not have come as a surprise when he published his first novel in 2017. This Is Memorial Device was genuinely unique, the work of a thrilling new voice, the reach of which was only fractionally illuminated by the novel’s subtitle, “an hallucinated oral history of the post-punk scene in Airdrie, Coatbridge and environs 1978-1986”. But in short, it acted as a hymn to the power which manifests from DIY art, seeing magic in places and times few writers had noticed previously.

Graham Eatough developed a successful stage play from the book in 2022, which in turn has birthed a new record, This Is Memorial Device: Music From The Stage Play, due on Geographic on 28 June. The album’s songwriters and main musicians Stephen Pastel and Gavin Thomson (who also did sound for the group) are only one small node in the Memorial Device rhizome (the LP also includes three other Pastels for example), and the full picture could be called a described as a kind of working class, Celtic, post punk scenius.

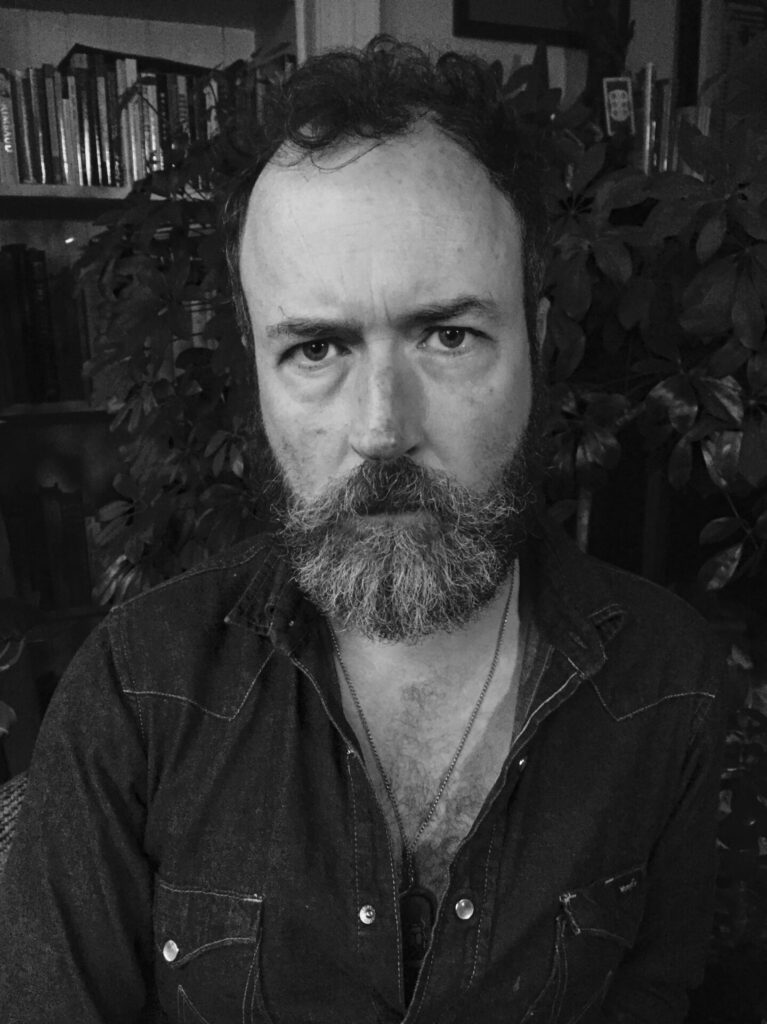

Stephen Pastel interviews David Keenan

Stephen Pastel: It’s been an incredible privilege to work on the theatre production and soundtrack of This Is Memorial Device, and to have you closely involved in both. From the beginning it has always felt like proper teamwork. By contrast writing is so solitary and personal, I can only imagine that when you were working on the novel you had no idea on whether or not people would like it or if it would even get published. Can you talk about some of the differences between making the original work and being a collaborator on the versions?

David Keenan: Well, I always say that everyone has their own Memorial Device and so in a way I never think that the book or how other people might picture it in their minds really belongs to me. Of course, every writer dreams of creating characters and situations that literally step off the page and have a life of their own and that is at the core of what I do. I believe in the magic of the aleph-bet, that letters are atomic, that words are magic, that sentences are incantations and that books are God-works in God’s shadow and that, when coded precisely, they are living entities and complex systems that generate a reality. That you can literally conjure objects and people to life using letters, using words. So, with that in mind, all of my books belong to whoever experiences them, and the word experience is key. My books are written not to be taken apart for meaning, not to be solved, my books are not about any one thing, any idea or really making any point whatsoever. My books are made to be experienced. When people ask me what a book like Monument Maker is ‘about’ I always says that Monument Maker is about the experience of reading Monument Maker. It’s not about anything else. It is not a commentary on a thing, it is the thing in itself. And so, when I see other people’s interactions with the book it’s amazing to me that they are not really ‘critical’ engagements, rather, they are creative re-stagings of the thing in itself. They are about the enthusiastic experience of This is Memorial Device. Result!

During the pandemic it became clear to me that having an audience to interact with is something that’s important to me. I mean, I have written many more books than I have published, so I don’t believe every single one needs a readership or even needs to be published, some books realised themselves just by being written and so afterwards I just filed them away. Who knows what they came along for. So, I have a parallel career in private and in public. But I love interacting with people and talking about my books all the same, I’m a fan and an evangelist and I could talk about art and music and literature forever, because they changed my life. So, being a collaborator was a lot of fun to me, even though I am essentially a solitary creator and not really a collaborator by nature. I am very social when I am out and about and enjoy hanging and talking shit and drinking and partying, but I mostly prefer to be at home, working. Solitary creation appeals to me and is my favourite mode. I am pretty chill about collaborating once I know I can trust the vision of whoever it is that has taken it on. And very early on, obviously I knew you totally got it, but I didn’t know anything about the director Graham Eatough, the producer Neil Murray or Paul Higgins, who plays Ross Raymond. Once I met them, I knew that they got it and that I could trust them completely, and so aside from the early days in Edinburgh where me and Graham live workshopped the script, I’ve been pretty much hands off. I love seeing other people’s visions of my books and this one was simply spectacular; it was a true experience, like the book, it understood the magic that I am talking about, the transformative power of language and movement and song. It became a magic ritual, which is exactly what the book is. A spell. It’s out there, living its own life. I believe there are endless iterations of This Is Memorial Device.

SP: You’ve been very open about how emotional Graham Eatough’s adaptation and our music has made you feel in different moments. Do you remember the day you came to the Old Hairdressers for one of the first run throughs? I remember catching your eye – you looked so intense, I thought you were probably really into it. Paul Higgins, our actor and amazing front-person, had never met you and thought you were hating it – he was trying his best not to look at you after a while. Can you describe some of your feelings in that moment and in subsequent performances and playbacks?

DK: Ha ha ha! I had no idea I was coming across that way. I was nervous because I had never seen Paul in anything, I don’t have a TV so didn’t know him from Line Of Duty or The Thick Of It. In moments like that I always try to be respectful, so I tried not to be looking at Paul too intensely, but I was really focussed because I told myself before I walked through the door that I was going to allow myself to be completely honest about how I felt about the presentation. And so, I tried to remain impassive and just absorb honestly. And of course I was blown away. But I didn’t want to affect his performance by any reactions I might have. Paul had the intensity of Ross Raymond, there is something religious to Ross’s devotion and Paul brought that completely. I was shocked, actually, it was beyond what I thought we might have achieved. I mean, I really enjoyed the initial Edinburgh staging but this was clearly something else. A profound reading of the book. I guess it’s part of Paul’s intensity that he would think that. That’s why he is Ross Raymond. I feel the production has deepened my own relationship with the book and the characters. I cried every time I watched it. I love that band so much, and those times. To be able to enter that world from a whole other place was a true gift.

SP: A few weeks ago we went on a field trip to Airdrie with Gavin Thomson (who I made the music with), and Steven Gribbin (who photographed and filmed the trip). We went out through the east end, through Shettleston and then Mount Vernon and Coatbridge which were important landmarks in different ways. When I was thinking about what we’d done with the music, our intentions and how it came out, I realised that underlying it I had wanted to try to convey a different geography, a different time – that Airdrie then, isn’t Glasgow now. But even Airdrie then, isn’t Airdrie now, is it? Yet, there is still something… a constant. With you as our tour guide, I experienced it so differently to how I would have otherwise. I felt that like Ross Raymond, you were standing up for Airdrie. How do you feel about Airdrie these days?

DK: I mean, I will always love Airdrie. It’s where I was gifted a perfect idyllic childhood with a loving mum and dad and a happy family life. It’s where I first fell in love, discovered music, became obsessed with going to the library and reading and writing, where I joined the astronomy club and got calligraphy lessons from Mr Scobbie in his mad eccentric book-lined house on the main street, dogged off school to have sex with my beautiful girlfriend in her mum’s bed, saw my dad get into so many fights, visited my grandparents in Calderbank, discovered Book Of Airdrie, edited by Mr Scobbie, and realised that I was living at the centre of the world; that Airdrie had books in it, and ghosts, too. But then as I got older, I was determined to get into Glasgow. There is a lot of longing in Airdrie, a longing to be elsewhere, even just twenty miles or so west in Glasgow; people who live there often feel like they have been condemned to the arse end of the world, and I rushed off and never came back, except for briefly, once, in the 1990s and then again, briefly, when Heather Leigh and I lived with my mum and dad in the early 2000s while we were looking for a flat in Glasgow. But I have always returned, in secret. Over the past few decades I have taken solo trips to Airdrie on sad drizzly days and photographed it, so I have a record of its changes. I only shoot in black and white and try not to include any people. My Airdrie is empty and haunted. Except for one eccentric tramp who seemed to wander into my photos like a ghost. Some of these pics we used in the play and have included with the LP and CD of the soundtrack. And yes, it has changed a lot. I still believe in it, but sometimes it’s hard. There really isn’t a decent boozer there anymore. I used to drink in the Wetherspoons there but even that closed down. I still like the little greasy spoon halfway up South Bridge Street, they have the most vinegary brown sauce there ever. I love vinegary things. But there are so many junkies on the street, so shady, like walking in front of cars to prove how hard they are, that kind of mentality. It feels like a dying town right now. Plus, people stare at me when I go out there because of how I look, like I couldn’t possibly be one of them. It’s nuts. One time me and Heather Leigh got on the train to Airdrie and some guy said to his mate, ‘Fuck me, it’s Tom Cruise and his wife.’

SP: Let’s talk about one of the highlights of the trip. Visiting your old house in Mount Vernon with its expanded garden due to your dad’s audacious land grab. In a way I cannot believe your dad did this – although knowing him a little I maybe can. Can you explain this bold move which I assume caught everyone (neighbours, council) off guard? What character traits do you think you’ve inherited from him and in what ways are you different?

DK: Yeah, when my parents moved from their flat on Willowbank Street, just off Woodlands Road in Glasgow, they moved into an estate in the east end of Glasgow in Shettleston that had just been built there on a field. Our house was at the top of the street on the corner and alongside it there was this kind of long, thin landscaped garden, this communal space next to our house which had a small front and back garden but nothing along the side, like everyone else on the estate. So my dad just built a brick wall around the side garden and incorporated it into our house. And no one said anything. I think if you are mental enough to do something like that you are probably mental enough to get in your face if you complain about it. And it’s still there; at points it has been replaced by a wooden fence, but part of the wall is still standing and that whole garden still belongs to that house. I loved living there so much but there was a mad criminal family living at the bottom of the street and it just became too much dealing with them all the time, so when we had the opportunity to move to Airdrie, we jumped at it. This was in about 1977.

My dad was someone who was out to seduce the world. He was a very sharp dresser and a handsome man, women would hit on him in the street all the time, it was insane. Plus, he was hard as nails. Totally fearless. He taught me to never be afraid, at least not of physical things. He didn’t like ghosts. Everywhere he went he would ask for “his discount” and I found it so embarrassing at the time. But he nearly always got it, except once, in Flip, in Queen Street, where he got reported to the store detective ‘cause they thought he was running a scam with the people on the tills. He worked most of his life in shoe shops and claimed to be the first person to ever innovate displaying shoes out on the street on racks on Sauchiehall Street. Who knows. He grew up during the Troubles in Belfast and was used to secrecy and lying and “telling them fucking nothing.” So there were a lot of myths around him. No one has been able to find out his real birthday, for instance. He couldn’t read or write but he had total faith that if he could read a book it would probably change his life. Of course, most books don’t change your life, but that’s when I made the vow that I would write the kind of books that would live up to an illiterate person’s fantasy of them. It’s one of the great sadnesses of my life that he didn’t live to see me become a published author. Not that he could have read them.

I certainly inherited his style; I mean I directly inherited some of his clothes and his rings and his hats that I still wear. My dad never wore casual clothes except near the end when he began wearing a big bubble jacket when he was in hospital instead of a dressing gown and my mum was mortified. My dad was into boxing and when he was young was a boxing trainer so I got into boxing through him too. He always said you should be the sort of man who when they are around no one is afraid. I love that line. He also had a naïve kind of joy in life, like the uncovering of simple facts would give him so much joy, also teaching these amazing self-same facts to others. He believed that the world was ultimately graspable in its totality if only you could be smart enough. He stuck a note above my desk once that just said ‘studie, studie, studie’, with every word underlined as well. He had to guess how to use punctuation, never mind how to spell, and so his notes and his birthday cards always read like mad avant garde poetry. Near the end of his life he told me he had written a book and that it was called Family Is Forever and would I like the only copy and when I said yes he handed me a book that he had stapled together with that title “by Tom Keenan” and that consisted of all the birth certificates he could find for his family running back, all except for his own, of course. I still cry when I look at it. Plus, he gave me a present of his final cardiograph before he died. Literally, a record of the shape of his heart. I always mean to get someone to put a musical stave over it and play it like a composition. Though he was hard and always in fights – I once saw him put a man through a plate glass window on holiday – he was so tender and loving with his family. Despite his lack of education, he was able to tell his children he loved them all the time. He called me his golden-haired boy, even though I had dark hair. His entire goal in life was to be a father and have a family. My mum was exactly the same. I was so lucky. So yes, I think I inherited his style and his lack of fear and his naïve awe in the world. And hopefully his loving nature. I’m just not as mental, ha ha. Though some people might dispute that.

SP: You’ve sometimes surprised me by the music you’ve become obsessed with. Things that I had in my mind that you hated. I love that. Can you give me an example of something that you spectacularly railed against and now love? Was Big Patty’s Relate epiphany based on a personal experience?

DK: These days I honestly have no standards at all. I’m open to everything. There’s a passage in Monument Maker about this, it refers to a time when Heather Leigh and I went to a music festival on a street in a tiny village in France. They had some covers band playing, the bassist had a five-string bass – this is France – and they were playing really inept versions of things like ‘China Girl’. And it was beautiful in the street – they were serving mussels and craft beer and kids were playing and awkward young punks were sulking and girls with sunburn were dancing in their summer dresses and I noticed that the guy in front of me had some kind of disease where his ear was rotting. He was playing with his two angelic children who were so pale and lovely and otherworldly, and the band began playing ‘We Built This City’ by Starship and I was looking at this ear that was no longer an ear, these children that were no longer children, and hearing this music which was no longer the worst song in creation. And my heart opened. I realised that I had been discriminating between the things that I showed love to. I realised that by virtue of something being – the very fact of its is-ness – it was beautiful, impossible and holy. Everything became transparent and nameless. Which is why I no longer practice standards, except for The Lighting Seeds, who I will continue to hate in perpetuity.

SP: What is a memorial device?

DK: I think it’s a book, or an LP.

David Keenan interviews Stephen Pastel

You are one of the few rockers who can really pull off wearing leather trousers and you always had your own style, to the point that in the mid-80s you would see people in Glasgow all the time who dressed and looked like you. Where does your style come from and who were your style icons?

Stephen Pastel: Thank you. I was trying to make it up and be original – to mix different things that I liked and just to find my own way. I didn’t want to look like I was trying to copy anyone. I was into the way that Syd Barrett looked, but also Epic Soundtracks, early Beatles and the Subway Sect. A lot of ideas came from 1960s French Cinema – the way that young people looked in Godard and Truffaut films – Jean-Pierre Leaud in particular. And then British films like Alfie, although more Jane Asher than Michael Caine. I was into being a bit androgynous, a bit of a perv – I loved the way Adam & The Ants looked in Jubilee, especially Andy Warren. So all sorts of things, but in the end Annabel (Aggi), who was all about being original, was my biggest influence.

DK: ‘Truck Train Tractor’ by The Pastels is one of the greatest rock & roll songs of all time, up there with ‘Roadrunner’, ‘Ooh Poo Pah Doo’, ‘Splish Splash’, ‘Temptation Inside Your Heart’… I know it’s the question everyone dreads, but where did you get the inspiration for such a mad exuberant song? What was in Aggi’s Impressive Toy Orchestra?

SP: I don’t know, it came to me one day when I was walking up Crow Road towards Anniesland. It came out of another song that we had that was too self-conscious. I knew we needed to somehow cut loose and not sound like other groups who I thought were trying to sound like us. I felt that the parameters were narrowing and we had to get outside of that. It is stupid and exuberant but so is ‘Ya Ya’ by Lee Dorsey and ‘Container Drivers’ by The Fall, both of which I love. I remember the recording vividly. Going to Leamington Spa to record with John A. Rivers, lugging two Vox AC30 amps on the train, just setting up in his studio and totally going for it. With Aggi’s Impressive Toy Orchestra I feel we maybe overstated the impressiveness of it. It was just a bunch of stuff that was out of tune, and would not be tuned. But I love that recording, love that group. What a feeling.

DK: We worked together at John Smith’s on Byres Road in their legendary record department. How does it compare to working in Monorail these days? How have record shops changed?

SP: The John Smith’s record department was legendary but it operated in such a mad way that in the end it would have taken a very rich benefactor to keep it in business. There was quite an oddball collection of people working there, which Judi (the classical specialist, and by far the hardest worker) did her best to hold together. We were into great music and learnt from each other and blasted Sonny Sharrock and Dusty Springfield and anything with any connection to Elektra. Most good record shops are a bit eccentric and there are some similarities between John Smith’s and Monorail – both mixed styles between different people’s tastes to find a combination that works. John Smith’s was more fragile because there was a disconnect between all of us and the owners. Monorail is more unified.

DK: I wanted to ask about your relationship with Glasgow. I know it’s a city that we both love so much, it was fun recently when we took a tour together of where I grew up in the East End of Glasgow and on into Airdrie and through to Caldercruix. You remarked that it was really so different from Glasgow when you got out there, in what way? What is it about Glasgow that is so magical and that has inspired so much amazing music, literature and art?

SP: I love living in Glasgow. It’s in everything I’ve ever done – the way I made it, the way it turned out. With The Pastels we’ve tried to reflect the city in our sound, the sense of moving between sandstone tenements, the ragged possibilities in the green spaces, the communities we’ve been part of. It’s complicated and sometimes you can over-romanticise it but there’s a real sense of home here. Moving out from Glasgow through the East End, which I’m not so familiar with, things start to change – it becomes less dense, more open. When we were in Airdrie and looked up at the sky and you said that it’s higher out there I could see that – it was plausible. I think the landscape becomes less tended, rougher, it doesn’t feel like the same amount of planning has gone into it. There’s that row of shops with every conceivable building style of the past 150 years. But there is also a sense that things can happen there too, which I think is one of the most important themes of This Is Memorial Device. I think the most important thing is that you understand where you are and try to make it work for you.

DK: This is just me being greedy for memories but you got to know my dad over the years, he went with me to my first gig which was The Pastels and The Vaselines at Fury Murrays. Can you recall that gig at all? To me it was life-changing. Are your parents still alive? What was your relationship like with your mum and dad?

SP: I remember it as a very chaotic show, even if your dad tried his best to give you a very orderly experience. My amp broke, our on-stage sound wasn’t good, I felt like we were a bit out of kilter with each other. But it was powerful too. It felt like the most people that had ever come to see us, who were into it, who really believed in us.

Your dad carried himself well. He was likeable and he knew it. Normal rules didn’t always apply. He’d come into John Smith’s to pick up something for your birthday from your stash, which was usually expensive items, PSF sets and the like. He’d always exclaim disbelief at the prices and then get down to the haggle which was his favourite part of the transaction – and my least. Cash was always king. “What can you do for me?” were the inevitable words. And then, “He’s a terrible boy.” But said with complete affection and love.

My parents were amazing people too. We lost my mum during lockdown, my dad a few years earlier. They were a tight unit – both practical in different ways. My dad was a very good musician. He played guitar and trumpet, and was very close to having perfect pitch. He would tune a guitar in seconds and looked a bit baffled that it would take me so long. He loved just sitting in the front room listening to records – mostly jazz. They were both very left wing, religious but progressive too. My dad would never hit me, he thought it was totally wrong. We were a close family. My mum was not nostalgic in any sense, she was always looking forward. I worried when we lost my dad, but she just kept going and was always interested in something new. She was an incredible reader. It became hard to find something that she hadn’t read in the library. The staff were always saying she was their best customer.

DK: Who was the most fun rocker to hang out with ever and why?

SP: The most fun for me was definitely mid-80s Eugene (Kelly) and Frances (McKee). I had got so that I just liked being with Annabel (Aggi) all the time but she needed to go to Brighton to study Illustration which Glasgow School Of Art. I was lonely so I just befriended them and they let me hang out with them and we’d go to stuff together and sometimes get really drunk or maybe, once or twice, take acid. They were kind and open, both really soulful, decent people. That was how The Vaselines started – Eugene gave me a cassette and I heard their voices together and just thought they sounded sensational and wanted to help them. I still love them. The Vaselines weren’t really built to last but somehow they did, They wear it well – slightly jaded minimum hassle warriors.

DK: Every time I see the cover of Swell Maps A Trip To Marineville with its suburban house gone up in flames I think of you. Can you tell me a little bit about how and why Swell Maps were so important to you?

SP: Buzzcocks were the first group I fell in love with. They were important to me in so many ways and still are. I felt they were very official – their logo; them being on United Artists; them having hit records. There was something very unofficial about Swell Maps like it had all just landed together by accident. I identified with the cover of A Trip To Marineville of course – living in the suburbs, maybe feeling a bit contained. Swell Maps were accessible, intimate, you could get to them. Musically they were much better than I realised at the time. Epic Soundtracks and Jowe Head were a brilliant rhythm section, always keeping it interesting even if the songs were sometimes straightforward. It was everything about them – their mode, their inventiveness, their joy. It just connected so much with part of my teenage self. I have to say I don’t go back to them as often as I do some of their contemporaries – TV Personalities, The Raincoats or Orange Juice. I think I maybe overdosed on Swell Maps or lost some of my connection to their lyrics. But as a mission statement, “Do You Believe In Art?” Of course, forever.

DK: I think we can agree that working on This Is Memorial Device and seeing the play so many times has been a transformative experience for everyone involved – it genuinely felt like making magic and the music is so perfect. Can you talk a little bit about how you approached it and the effect it has had on you?

SP: The opportunity to work on This Is Memorial Device came at a good time for me. We weren’t doing any Pastels music and I knew that I wanted to take it on, but only if you were into it. At the outset I felt the book had such a strong identity, we needed to absolutely match that with the music. When I found the tapes I’d made with John McCorkindale (Corky) in the early 80s, the Unexpensive Superstars stuff, it just felt so instantly right and I thought, ‘This is is it, this is the way in.’ You and Graham (Eatough) were both really supportive. At the start of it all Katrina (Mitchell) wasn’t available so I decided to work with Gavin Thomson, our live sound engineer. His perspective on what we were doing was really practical but also he loved the book. His input wasn’t just editorial – we made most of the music together and had a shared vision of what it should be. He’s been such a great collaborator. We both had an absolute belief in what we were doing and decided to make the record whether or not the play was ever re-staged. We were both totally consumed by it. At every stage we tried to respect how much the book means to people and the sounds they hear in their heads when they read the words. We were especially wary of putting something down as Memorial Device but what we’re playing in ‘I Started Painting Landscapes’ is Andrea Anderson’s memory of how they sounded in the rehearsal room. We’re not trying to pass it off as them, even if Andrea comes across as one of the most reliable witnesses. It meant a lot to us when you said Chinese Moon sounded exactly as you imagined them, like a bunch of slightly inept kids trying to be Fripp & Eno.

DK: On the Unexpensive Superstars recording ‘We Have Sex’ there’s an amazing line, “We knew we were right about art.” What were you right about?

SP: Unexpensive Superstars never discussed lyrics – it would have taken too long. We just wanted to get stuck in and make our music, no messing. On ‘We Have Sex’ I could make out some of John’s words as I played and other bits were just unintelligible, and still are. But “We were right about art” is an amazing line, like we’d been arguing our case for decades on the barricades alongside John Berger or whoever. John (Corky) was great like that, totally uninhibited and wild. We were probably trying to make each other crack up. I’m sure some of our songs dissolved into laughter, they were so out there. But we were right about art – we took it at face value. It wasn’t just important to us, it was everything to us – amazing images, sounds, ideas, inventions. It made our lives.

This Is Memorial Device by Stephen Pastel and Gavin Thomson is released by Domino on 28 June