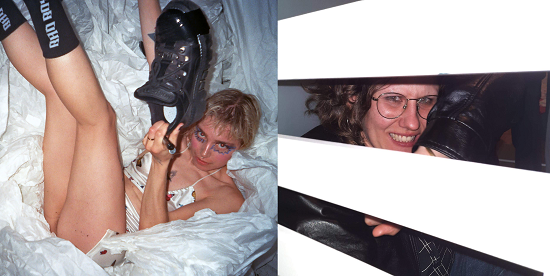

SIKSA’s Alex Freiheit and Justyna Banaszczyk, aka FOQL

Music writers. Who needs ’em? We recently had the opportunity to get two of Poland’s most interesting musicians, Justyna Banaszczyk, and Alex Freiheit, together (over the ether) and left them to have a conversation about their individual practice, without any interference.

Banaszczyk is an experimental electronic musician under the name FOQL, plays in noise duo Mother Earth’s Doom Vibes with Edka Jarząb, runs the label Pointless Geometry, the venue Ignorantka and more.

Freiheit is a spoken word poet and singer, one half of the band SIKSA alongside bassist Buri, who blend punk, theatre, literature and intense avant-garde performance. Their latest project is The Uses Of Enchantment, which incorporates fairy tales and fables. She also runs a venue called Latarnia na Wenei in her native Gniezno in central-western Poland.

SIKSA are one of the bands playing the last-ever edition of London underground music festival Raw Power this month, which takes place August 24-26. You can find tickets and the full line-up here. Banaszczyk will release her new album as FOQL, Wehikuł on Septemeber 9 via MAL Recordings, check back in with tQ for a full review in the coming weeks.

SIKSA’s Alex Freiheit interviews FOQL, aka Justyna Banaszczyk

You are a DJ, producer, and label curator. You organise shows and events. You are the co-founder of Radio Kapitał & the Oramics collective… I could go on. How do you see or describe yourself? Which part of your work is most important for your identity?

Justyna Banaszczyk: That’s all true, and I identify myself equally with all these disciplines (perhaps least with the DJ part – I refer to myself as a ‘TJ’, i.e. tape jockey, or just say that I play music). I don’t usually separate the different aspects of my life. I don’t divide it into my art, my job, my activism, my private life, etc. Who I am and what I do are a whole, and the most important aspect of my identity is my quest for emancipation.

When you started out and during your artistic path, did you find space and time for such music and art as yours? Or did you have to (re)invent it for yourself?

JB: When I started out over a decade ago, everything was completely different. We didn’t have as many collective grassroots initiatives or inclusive spaces open for experimentation; there was no debate about these things either. The city I come from, Łódź, was a nightmare in terms of aesthetics and the local creative circles. Nothing seemed to change. When I chose to escape from Łódź, I understood that you can build an artistic community – and just create in general – in a totally different philosophy. Had it not been for this step, my life would probably have taken a completely different path.

Only now, years later, can I appreciate the tremendous influence – on myself and my art – of having met people who opened up my mind. We kept reinventing ourselves from scratch. Perhaps this is why I care so much about the community factor of grassroots art. Grassroots being the crucial word here. Art understood in market terms doesn’t interest me in the slightest; I find it disgusting. I think the greatest problem of grassroots art communities in Poland is that they’re systematically consumed by the system, which is all about instant profits. It takes time for a bond to form between people. And this process is just not compatible with an atmosphere of populist, nationalist, hypercapitalist invigilation fuelled by the Catholic ideology.

A lot of your work is about building a community. During the artistic process, when you work with sound, do you think about the audience and community in advance?

JB: Creating bonds between people is important but paradoxically, I’m also a rather introverted and quiet person. My creative process usually takes place in complete solitude. I sometimes collaborate with other artists, but for that to happen, there has to be rare chemistry between us. To be honest, I don’t think too much about the reception of what I do or the impact it might have on people. Of course, apart from works meant to be experienced in a community, such as the Temple Of Urania installation. When working on an album, I never think of my compositions in purely political or social categories. I think that would be a huge limitation, bordering on propaganda, and that’s not something I’m interested in. I think in small narratives, stories and impressions. When I create, I enter into a dialogue with myself, my thoughts and my imagination. It’s a struggle, too, because I tend to give up easily. What I refer to as building a community happens later – during concerts, meetings, festivals, walks… And just spending time together with people I meet through art.

You are politically conscious and involved in the struggle. Do you see the frustrating political situation in Poland as a ‘fuel’ for your art, or do you feel blocked by it?

JB: At a certain stage of my involvement in feminist action, it really started to block and frustrate me. I was really tired that instead of a new album concept or how my latest work sounds live, I was always asked about law and justice or the Catholic church in Poland. The Western media, in particular, seem to be more interested in these things than art. It started weighing heavy on me, and I’m happy that I managed to push my work in a slightly different direction. I was also tired and burned out by seeing my art from the gender perspective. Being a free, brave woman in Poland is a political gesture in itself – you don’t have to keep talking about it.

You decided to move from the capital to Łódź, a big but still ‘provincial’ city. The decentralisation of culture is important, but I’m wondering how you see this from your perspective and experience.

JB: Łódź is not really a provincial city, though. For a long time, it was the second largest city in Poland, with a population of one million inhabitants – a population drastically reduced by the ginormous emigration after our accession to the EU. To me, the decentralisation of culture (and all other aspects of life) is pretty much everything, to be honest. Without it, society becomes drained, alienated, full of complexes and prone to being brainwashed. In Poland, this process is plain to see. I realise that had I stayed in Warsaw, it’d be easier to make a ‘career’, whatever that means. It’s all about the afterparties, the high-fives, and who you mingle with (oops, have I said it out loud?). I’ve chosen a different path, though. As usual, the more difficult one! Łódź is a classic example of a love-hate relationship. On the one hand, it’s fascinating and intriguing, a black sheep, like any other run-down industrial city in the world. It suffers from the typical set of post-industrial problems, too: poverty, social exclusion, lack of identity. Now, when I’m all grown up and conscious, Łódź simply inspires me. And it’s a good hole for poor artists – living here is cheaper than elsewhere.

Do you see running a venue, Ignorantka, as a new chapter in your life or a logical evolution of your artistic path and work, just with different tools? By tools, I also mean the delicious pickles made by your lovely mum!

JB: That’s how I think about it, although I don’t talk about it too often. Running a bar / event venue / meeting place feels like a non-stop performance. I mean it!

Ignorantka is a unique, local space with a long history where a lot of different people from different worlds have a chance to meet. Is it satisfying, or do you want to do something more with it? Maybe you have in mind some ideal image of your place, or you want to observe the process of those meetings?

JB: To me, this specific mix of people you’ve mentioned (our customers include artists, pensioners, professors and local small-time criminals) is a key to discovering myself. I often say that I also come from a poor working-class family. This is a very strong component of my artistic identity. I think that because of it, I am sensitive to details that people from more privileged backgrounds are oblivious to. For me, it’s really important to have elderly gents meeting upstairs for a pint with an experimental concert taking place in the basement. Everyone talks about how harmful it is to be locked in your own bubble, but not everyone is able to leave them. We only manage because this venue has such a long history. That’s not our doing, more like a stroke of fate.

FOQL

Łódź is a city with a lot of stereotypes and false images. Speaking about the local music scene: black industrial, old school techno, cold wave – it’s all there, but not just that. I’m interested in how you see Łódź in this particular moment, from your space and perspective.

JB: There’s a lot of space in Łódź to do your own thing. The old-school scene you mentioned is history. Łódź used to be the place for hardcore punk; this is where the first squats in Poland were created; the techno/rave scene originated in Łódź, as well as the experimental industrial scene. This is also the birthplace of avant-garde art in Poland.

And yet I don’t feel like I need to refer to what’s played in other clubs around the city. Our profile isn’t meant to pander to stereotypical local tastes. We do what we like and what intrigues us. I strongly believe that interesting movements in art or music were sometimes born before the eyes of a handful of people. Attracting crowds should not be an end in itself.

You organise live shows; you are a curator; you release records, prepare mixtapes – and for all that you have to make a ‘choice’. What’s most important when ‘making a choice’?

JB: I’m guided by intuition. It sounds pretentious, I know, but I can’t help it! I have an internal aesthetic/ethical compass, and I follow it. I‘m after honesty, an internal imperative to create. Some people just have it. They create because they must. That intrigues me.

Do you experience your artistic path as a continuous process? Or do you see it as parts, bits, chapters? Do you feel satisfied with all your previous artistic works and decisions?

JB: Like I’ve said, I don’t really separate my life from my art and creative practice, so it’s all just one continuous flow. I think my aesthetics has greatly changed over the years; it keeps evolving. I don’t evaluate myself. I just keep going. I’m definitely over some of the sounds that used to really turn me on, but then again, I didn’t like spicy food, and now I eat chilli for breakfast.

You have a lot of experience with collective work. What does ‘collective’ and ‘collective work’ mean for you?

JB: I don’t really know how to answer this question at this stage of my life, but in most general terms: a lot of work! A lot of emotions, a lot of compromises (which are sometimes impossible), but also the irreplaceable possibility of meeting the most amazing people from the most distant bubbles. There’s nothing more beautiful than a group of people who want to do something for the common good. It’s really difficult, too, but that’s a subject for an entirely different conversation.

Which element of playing your own live shows do you like the most? I’m asking about the whole process, from the first email to returning home after a gig or tour.

JB: I love to feel this ephemeral bond with the audience. It’s hard to put into words – you just feel it when people really bond with what you do onstage. That’s a good compensation for stage fright. Generally speaking, all sorts of stage shows eat up a lot of energy, but the dopamine kick you get in return… It’s pretty addictive!

Are you happy?

JB: I try, but it doesn’t always work! But right now I guess I am because my new album Wehikuł will be out Septemeber 9 on MAL Recordings

FOQL, aka Justyna Banaszczyk, interviews SIKSA’s Alex Freiheit

What’s it like to be an artist in Gniezno, and why did you choose to stay there?

Alex Freiheit: In the past, when I was teenager I wanted to burn down this city. Classical girl from small city story. But I know why I wanted to do it. I didn’t want to ruin this city itself but the concept and spirit of patriarchy which is everywhere here, I guess, and of course bad memories and experiences connected with rape, violence, and growing up in a conservative environment. Also, I was bored. I thought that I could only experience art and culture in big cities. That was always a life-saver for me, from childhood. So that is why me and my depression moved to some bigger cities like Poznań, Toruń where I met Buri [half of SIKSA], and finaly Ankara. In Turkey I decided to go back to Gniezno and faced old spirits, old relationships, people and places.

Places like bars, clubs, cafes, parks, squares are so important for me. It’s a precious to have a favorite place in the city where you’re living. Somehow I felt that big cities are not for me and I was like: “Ok, Gniezno, let’s try again”. But this time on my rules. I recorded an album about my relation with this city which is PALEMOSTY NIELEGAL [I Burn Bridges Illegally in English]. It’s a story about girl who is exploring city Gniezno with her friend, doing stupid things, small crimes, and looking for some guy from the past to kill him. At the end it turns that Gniezno is this man and the girl and Gniezno are dying together with the view of Jelonek Lake at the end.

For me Gniezno is still hard to deal with sometimes. But it’s good because here most of the people don’t give a shit about what we are doing in art fields, so we are out of the bubble and it’s good for our ego. Quickly we started to organise things connected with art in this city with our friends. We are not playing gigs here, we are saying that organising things here is like playing concerts. Thanks to SIKSA we know some people and it’s easier to invite them here to play or do some workshops but also we are very open and careful to know what is happening in our city. We know what people are creating here and really our job is to give them space to show it. At least that we can do, because you know how hard is to get to the top and, for example, show your work at a gallery.

Tell me about the venue you’re running, Latarnia na Wenei. What are the inspirations

behind this place?

AF: It’s an open air venue that we are running with friends from our city. From June until the end of the summer we are organising gigs, workshops for kids, teenagers and adults, meeting with writers, and other events. Almost every day something is happening. It’s a place close to the city centre, near the almost dead Jelonek Lake. But it’s very beautiful there. We are really meticulous about who we are inviting cause our audience is very varied. During the concerts you can see in the audience kids who are running around and having some fun around or listening, children who are coming with grandparents or parents, teenagers, some funny guys who are a bit drunk but happy that they can drink their own beer and listen to some sometimes not-so-easy music. We have lot of respect for our audience and we like this diversity. We are treating this as a gift because thanks to the work of lots of people and our audience, artists who are coming can feel this atmosphere and they feel that their performance. People are talking with us about artists they’ve seen even weeks or months later.

One year ago Jozef van Wissem played, it was a beautiful concert. We have a soundguy named Janusz who was a bit stressed about having Jozef here, but he did a great job and one week later somebody met Janusz on the street and said: “Congratulation for the sound work on Jozef’s concert because I believe it wasn’t easy”. What I also like about this place is that it isn’t a bar so people are coming there for events, not for drinking. It’s a really special place but we are afraid for its future. Right know our biggest problem is so called “revitalisation” near this place. They are calling this revitalisation but you know that in fact means gentrification. We want to prove to our city municipality that art and culture also can be a big selling point for the city, not just this old story about how Gniezno was the first capital of Poland, had coronations, a cathedral etc. All those historical things are still number one in our city.

What is the biggest misconception about SIKSA?

AF: That we are doing things to provoke and nothing else. That we are doing loud things because we want to be visible, loudness just to be loud, and without this we are nothing because it’s music without artistic values. Some people still are saying to me after they experienced our first show in their life: “I thought that you were mean and wanted to provoke, but I felt nice during your show.” Also, I don’t like when people from polish mainstream are using one word to describe us: controversial. Please stop!

Are there limits to radicalism in art? If so, what are they? If not, why?

AF: I don’t think so. I think that there are visible boundaries in society but not in art. Also, I belive that sometimes art can be radical for society but the artist didn’t think about it that way. Me personally, I don’t think that I’m doing something radical, people just tell me that.

If you had the power to make just about anything happen, what would you do to make life easier fast for independent artists in Poland?

AF: First of all, artists need a space for work and where they can show their art. A municipality need to support all forms of small artistic communities and venues. As you know, in Poland all forms of authorities don’t respect even long term cultural activities like, for example, Warsaw’s famous Pogłos club. The significance of DIY places for cities is inestimable, very often clubs or venues with international recognition are more famous in certain city than touristic aspects. With a stable net of venues artists the scene itself could also be more stable. The second important thing is solving the problem of status of artists themselves. If you don’t run business activities as an artist it’s hard to describe what you even doing with your life. Help with social insurance, pension contribuions etc would be helpful.

You’ve recently been playing outside Poland a lot – how do people react to your

performances? Do you think that art created in Poland is understandable outside our

country, or do we focus too much on our own shit and too little on universal things?

AF: They are treating this as music, not only lyrics with some bass in the background, so it’s refreshing for us to see people who are dancing during our performance. Right now we are performing a fairy tale which is kind of an Evviva l’arte statement, but also I’m singing and delivering lyrics with lots of voices, impressions and onomatopoeia because I’m talking as a mouse, a horse, a group of moles, a firebird and other creatures. So the form and sound is maybe more important for us now than ever. I’m always telling people before what it’s about, and we have a book with English translations. People sometimes are doing crazy things during our shows abroad.

In Torino we were dancing together, touching each other and laying down on the street at the end. We are simple creatures who want to give people simple emotions: anger, laughter, love, hope, happiness, but also a bit of sadness and of course madness. People understand those kind of emotions everywhere, it’s a fairy tale which has a universal, magical background in culture. After our shows they are telling us how they understood it and it’s always great. I know they won’t understand the lyrics but even though I’m using them so much I don’t think that they are so important because of the rhythm or scales of Polish language. Maybe I’m using them so much because they are helping me to feel, to love, to understand, to shout, to be free. On the stage I have no inhibitions and I like that the audience can feel also free to do crazy things. Also, I love that some people don’t just follow me running everywhere but they are only with Buri and his bass. Our shows in Poland and abroad are also a chance to talk about many things. I think that the kind of art that we are doing opens some things in your heart (of course not every heart, but thatt’s ok) so people really are talking, sharing, sometimes saying their secrets. It’s one of the greatest part of touring for me, to hear. And also – I’m talking, screaming, dancing for one hour for people – It’s my duty to listen even more than one hour after the show about their feelings. In short words – people understand that and language is not a problem. Could be, but we solved it.

What’s the biggest difference between the Polish independent music scene and what it looks like in the so-called West?

AF: Both there and here we have many brilliant and fantastic artists: in the west, east, central, north, and south always someone with a splendid idea will show up. Of course there are economical differences, but differences in art itself are something on which we could focus to better understand each other.

Are you sometimes tempted to leave activism behind and push your art in a completely

different direction?

AF: Our art never was and never will be only about political activism. It’s also about beauty and other artistic shit. Right know I need more escapism in my life, so that is why we did a fairy tale about art itself. So, you can see this change actually, right now. Some people always will treat us as activists who are doing songs about the political situation in Poland. We are not doing songs that people can order for their political menu. We refused to be that kind of figure years ago when I did material about rape. I didn’t want to be a superhero of Polish feminism or a statue for “smash the patriarchy” because it’s a form of capitalism and selling yourself. I like to see some ideas in the mainstream that are important to me but I prefer to do small things in Gniezno, you know? Also, we are half dead because of what is happening in the world right now and I don’t want to be only delivering bad news.

The theatre in Poland has recently had a lot of bad press (violence, mobbing, sexism,

Harassment…) What is your experience of theatre work?

AF: First I want to say that I had a beautiful experiences in theatre. I know so many talented people from the few works which I made. I remember that my first job in theatre was in Poznań where I met Agnieszka Kryst, a Polish choreographer. She opened my body, thanks to her our performances are about movement. I admire actors, their work is so difficult. But I will never do anything in Polish theatre again. I’m talking about it when I’m a horse character on stage in our fairy tale The Uses of Enchantment and that’s all I can do for myself to heal after few bad experiences. I don’t want to name names because I’m burnt out, tired and still trying to deal with all the words I’ve heard during my work in theatre. But I do want to say that theatre in Poland is stealing things from the underground and other arts: visual arts, performative installations, underground music, other cultures. Some people hire us because they had an wrong opinion about us and thought that we will do something “strong and controversial”. Which we refuse. I’m not talking about all pieces of course, but Polish theatre capitalises ideas more than it shows how Polish society works. It doesn’t bring any change, it doesn’t even search for solutions. It’s only eating hot, often political themes to stay alive. But I also worked with international crew in Switzerland and it was more of a performative installation connected with movement than classical theatre and it was so inspiring. I believe that I can still work in theatre because I love performing in other contexts. But only abroad.

If you were to leave Poland, what would be your destination? Are you inspired by the artistic circles in some particular city or country?

AF One day we want to die in the Czech Republic.

You’ve been working with a number of disciplines: music, theatre, performance,

literature, film… If you were to choose only one of them, what would it be and why?

AF: Music. Because we are musicians.

You’ve been observing the Polish music scene for a good few years now. What does it look like from your perspective? In what direction are we headed? Is there any hope left?

AF: I cannot see the direction and I love it. Seriously! I love how young people are treating music, how rap music started to be a field for so many different characters. I love that there is a young band from Gniezno who is doing old school metal and making it cool again. There is a crazy variety, a mixture of postmodern repetitions of past, futuristic and enigmatic online incomprehensibility and so on. We love the fact that as an audience we don’t have to understand everything around and its fantastic, just breath taking!

SIKSA play the last ever edition of Raw Power Festival, which takes place August 24-26. Find the full line-up and tickets here.

Banaszczyk will release her new album as FOQL, Wehikuł on Septemeber 9 via MAL Recordings, check back in with tQ for a full review in the coming weeks.