It was with no little ceremony that Adrian Utley presented his EMS VCS3 ‘Putney’ synthesizer to Peter Zinovieff, the man who had conceived it over 45 years ago. He asked Zinovieff for a signature on the machine’s wooden back panel with the repressed excitement of a true fan boy and I had to remind myself that this man had only a few days before been headlining the Latitude Festival with his band Portishead before a rapt crowd of thousands.

“To my fellow alumnus,” Zinovieff scribbled and signed, for he and Utley have more in common than a long mutual engagement with voltage control. At different times, they both attended the same school: Gordonstoun, a public boarding school in the Grampian Region once described by Prince Charles (another alumnus) as “Colditz in kilts”. Utley and Zinovieff, likewise, have little kind to say of their time there. They share reminiscences of tearful phone calls home and punishing six-and-a-half mile hikes across the Morayvian floodplains.

“It’s lovely to see it like this,” Zinovieff says, gazing fondly at the mylar coating and satinised finish of the Putney. The screen printed letters on the front panelling are a little worn and a few modifications have been added around the patchboard. “It’s not a museum piece!”

“Oh, I use it,” Utley emphasizes, at which Zinovieff is clearly enormously pleased.

But even then a certain note of misty-eyed regret creeps upon him. “I wish I had one myself now,” he sighs.

For a long time Peter Zinovieff preferred not to think about EMS, the pioneering synthesizer company he started from his home in 1968 which went onto supply vocoders and Synthis to Brian Eno, Karlheinz Stockhausen, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and members of The Beatles. Nor about the music studio he had built in his shed at the foot of his west London garden.

He had stopped composing music. No longer had he any of the equipment that the engineer David Cockerell (later of Akai, Electro Harmonix, and Pierre Boulez’s Parisian IRCAM studio) had built to his specifications.

The company itself had gone bust in the late 70s and, despite an attempt to found a national electronic music on the South Bank with the equipment from Zinovieff’s home, the funding had run dry and the gear itself was ruined by a flood in the basement of the National Theatre. When, in the early 21st century, techie magazines like Sound On Sound began writing encomiums to the lost British synth manufacturer, they would note that its founder now lived on a remote Scottish island, conjuring up an image of some King Lear of electronic music, roaming the heaths and cursing his progeny.

Then a little less than ten years ago, Zinovieff came to London for the day with his wife. She had some work to attend to at Imperial College so Peter elected to pass the time wandering around the Science Museum next door. Reunited later in the afternoon, she found him ashen-faced. “They’ve got a Synthi in there,” he told her, astonished.

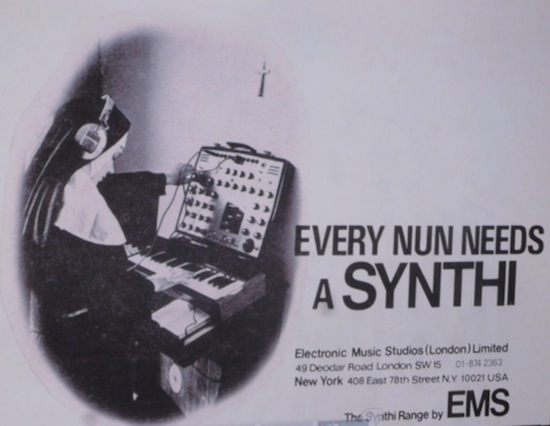

He had stumbled across it, quite unexpectedly, in a vitrine marked, great inventions of the twentieth century, next to a toaster and a microwave oven. The juxtaposition is not as odd as it first seems. EMS, arguably, had done more to domesticate electronic music than any other studio or company. “Every Christmas needs a Synthi,” they had once insisted – and more. In a whole slew of late 60s ads, EMS had sought to persuade magazine readers that “Every picnic needs a Synthi”; “Every school needs a Synthi”; “Every opera needs a Synthi” – this illustrated by a production of The Magic Flute in the then-impossibly futuristic year of 1983, taking place in an oak-panelled room bedecked with analogue synthesizers – and finally even, “Every nun needs a Synthi”. It was a house rule that anyone who came to the studio in those days would stay for lunch. Prospective new employees were taken on holiday to the Scottish Highlands.

The EMS studio was also far more open to visits from pop musicians than other electronic music studios, helping to usher such strange sounds into the home. Though it had little to do with Zinovieff himself – who admits to us he used to be “terribly snooty” when it came to popular music – those lunch guests did include the likes of Pete Townshend, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, and King Crimson. None of whom, one imagines, would have been nearly so welcome inside the hallowed perimeters of the GRM in Paris or Stockhausen’s studio at the WDR, Cologne.

Moog, of course, sold plenty of machines to rock stars – but he didn’t invite them round for tea. The Hollywood studios where Moog sales agents Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause struggled to show The Doors and The Monkees how to use a modular System 55 seem a world away from the more down to earth environs in which EMS once operated.

Adrian Utley first really became aware of EMS machines upon seeing Hawkwind perform with Michael Moorcock at the Reading Festival in 1975. The sound, he recalls, was “earth shattering” and has stayed with him ever since – even inspiring a passage in the Portishead track ‘Threads’ on their last album. It would be nearly a quarter of a century before he could afford a Synthi of his own.

Adria Utley: For me, in the 70s, just after school, the VCS3 was a legendary synthesizer.

Peter Zinovieff: Was it already, then?

AU: It was. It seriously was. To me and my friends. Moog synthesizers and VCS3s – there was no way I was ever gonna have one. They were out of my reach, completely.

PZ: Because they were expensive?

AU: Yeah, I mean a packet of cigarettes was expensive to me then. I had the same guitar forever! They were legendary because they were on lots of records we bought. Brian Eno used them on ‘Virginia Plain’ and what is that sound in the middle?

PZ: A VCS3 was meant to be a cheap synthesizer with all the modules in it. My philosophy was, it should be as cheap as possible. But on the other hand, I remember it cost £330 and now translating that £330 into today’s money is £3,000 or more. So it must have been, at the time, expensive. But then everything was expensive at the time, to do with electronics. Electronics itself was so new.

AU: It was your world there.

[Utley is gesturing towards the monitor of Zinovieff’s PC. The screen displays an old black and white photograph of a narrow room – Zinovieff’s old shed off the Putney Bridge Road – with walls lined bottom to top with rack-mounted electronic modules. This had been the beginning of EMS: a hobbyhorse gradually accumulated for the sake of relief from what Zinovieff has described as an “incredibly boring job” carrying out war game scenarios at the British Air Ministry.]

PZ: These were just ex-army stuff from junk shops so these didn’t cost a lot of money. This filter, for example, probably cost £20 or something. They weren’t expensive because they were junk. This would be pre-computer.

AU: I was thinking about your computer…

[Zinovieff may well have been the first person to have a computer in his own home (he’s also a strong contender for inventor of the first sampler). It became necessary. Having acquired so many junk shop filters and army surplus oscillators he needed something to streamline the system and keep it all under control. Apart from anything else, cutting up pieces of audio tape into all the tiny little bits necessary to produce any kind of complex sequence of sounds was simply “much too fussy”.]

PZ: When I got a computer, all of this became superfluous because David Cockerell then made me voltage controlled stuff. Who would turn a dial when you could just put a number in? Although, the computer itself was incredibly basic. There was no screen, no hard drive…

AU: It was just a digital readout.

PZ: There was no digital readout.

AU: Nothing.

PZ: Nothing. Just a tele-type. So the tele-type would print out – very slowly tap tap tap tap – and you could type in on the tele-type. That was all. And there was a paper tape. Punched holes. So the whole thing with programming was, by necessity, extremely slow. You would put in a few commands and then you would see if it worked and it would print out and you’d correct it. So it took ages and ages to do absolutely anything. When you switched on the computer, nothing happened. There was a light. And then you had to programme by turning switches on the computer so that it would read a paper tape which would read a longer paper tape. It took twenty minutes before you even could do anything.

AU: So what was the sound generation of that?

PZ: The computer had no sound generation. All it did was to give out a digital command to a digital-to-analogue converter which then controlled the equipment which David Cockerell had built for me.

AU: From digital to control voltage.

PZ: Then later it became digital to digital. But at the beginning what happened was, I would say to David, I really would love to have some oscillators. And he’d say, alright, here they are. And he’d give me a box and he’d have a handwritten thing, these are the codes. And that was it. So then I had to try typing in these codes and seeing what happened. So I had to build up the language to communicate with this computer, which cost £140,000 in today’s money.

AU: Wow!

PZ: So it was a gigantic, gigantic family investment of mine to realise that computers were going to be the future and that the only way forward was not this – [he gestures dismissively towards the image on the screen]. It wasn’t to have gangs and gangs of stuff. Computers would be the way – and it is now. There weren’t integrated circuits in those days…

AU: Me and my friend Will Gregory, from Goldfrapp – we have lots of synthesizers together and we’ve done pieces with both of our VCS3s which both came from Ed Williams –

PZ: Who took over EMS for a while.

AU: Yes. He used to do performances with Will using VCS3s on Dexion trolleys. I didn’t ever hear a performance. Will had a VCS3 from then and I used to mess about with his. Then I bought mine from Ed, probably 12 years ago. It’s endless. Really endless. Because of the way you can patch it…

PZ: I had this massive patchboard.

AU: On the Synthi 100?

PZ: No, originally just in my studio. Four times as big as the patchboard on the Synthi 100. That was the beginning, before the VCS3. I wired all this up myself and I’m completely hopeless. I’m really bad at soldering. But on the other hand, there must be 25 kilometres of wire there. I couldn’t bear this thing of wiring all these things. So I thought, this is one thing that’s going to come out of here, into the VCS3.

AU: That patch bay! It’s very different from the Moog ones.

PZ: You can do things which are illegal.

AU: And it doesn’t blow up either! It drops a bit in pitch sometimes.

PZ: Yeah, of course it does, because the voltages are being taken away.

AU: But it’s part of the sound of the thing. I’ve never ever played it in a conventional musical sense. It doesn’t seem to be what you would do with a VCS3. It has another whole world.

PZ: I think what I thought was, if I could have bought all of these together, this is what I would have liked. Instead of collecting all this – [i.e., the banks of modules in that black and white photograph on the computer screen] – I would have liked to have started with something like a VCS3. That was it. Luckily there was David Cockerell who could say, ok, it’s easy. If that’s what you want, I’ll do it. And then there was Tristram [Cary], of course, who designed this nice box.

AU: So, with the VCS3, what were you thinking?

PZ: It was only to support the studio. The studio was so expensive and became more and more difficult. I got very ambitious. David Cockerell got ambitious too. I wanted 400 oscillators. The last thing we built was those two things up there – [he gestures towards a couple of big green circuit boards stuck to the wall above the door] – which, again, is a bad story because it worked for two seconds. It was a digital filter bank with every filter controllable digitally. I’ve had somebody make a simulation in Max/MSP for me but it’s nothing like as good as that would’ve been. With the VCS3, every sale meant I could buy more equipment. But on the other hand, when it started to sell a lot, it meant having another secretary, it meant working with this factory. And I had to go down to this beastly factory and say hello to the girls working there. I was like a businessman.

AU: Which you didn’t want.

PZ: I didn’t want it at all. I don’t know if you find this a problem or not?

AU: To?

PZ: Well the fact that if you do something successful, it’s going to detract, in a way, from your own personal work.

AU: Well, it’s a different kind of story. There’s three of us in the group, you know…

PZ: Yes.

AU: And we have other people who play live with us, within Portishead this is. Last year, we went on the road and there was an entourage of 30 people and two planes. We’ve got two aeroplanes that we rented. And I was thinking, how did we get there? We’ve got this giant thing going along. But I think we want to make it go smaller again.

PZ: It’s very tricky to do that isn’t it?

AU: I think it is, but I think we can probably do it. I think it’s more difficult if you’re running a business in terms of a production line, making things, to then make it smaller. But I think we can do that. We’ll find a way.

PZ: EMS was such a nice company. The tragedy was trying to get too big – or people trying to make it too big. We got in the hands of crooks in America who wanted to make it public and the thing went broke. It was a terrible story and it was all part and parcel of us trying to get too big and thinking it was good to get too big.

AU: I was going to talk about Harrison Birtwistle and that area of music.

PZ: That’s what I was really interested in – and still am. I had lots of lovely collaborations with Harry Birtwistle. Do you know him?

AU: No.

PZ: Very nice bloke.

AU: I’m not really trained in that world but I’ve been teaching myself over the years. I’ve just become interested in his music more. I really like what you were doing. How did that happen? How did that collaboration work?

PZ: Well, in those days, it was so difficult to control the studio. So the only person who could do it was me. Composers like Harry Birtwistle and Hans Werner Henze – who I worked with a lot – they realised immediately that there was no chance of them having their hands-on in something which they couldn’t possible understand. So their way of communicating with me was to say, I like the idea that it should be really gritty. Alright. So I would say, I know exactly what you mean by “gritty”. I’ll work on it and produce something gritty. And then I’d produce something and they’d say, well no, perhaps it should be longer or something. And then somehow I understood what they wanted and I was able to interpret it and we were able to make a collaboration. It was a brilliant way of working.

AU: Did they have any kind of graphic score? Or any kind of score?

PZ: There was a score for the orchestra. But for the electronics, no. It was mainly conversation, sellotape, and scribbles. Birtwistle was very good with quick drawings and sellotape. So we’d sellotape these big strategies together. Otherwise it was my imagination and their imagination plus the limits of what was possible.

AU: The Birtwistle stuff seems to be extremely specific in composition.

PZ: It is specific. It was very disciplined. But if somebody like Birtwistle came now and said, ‘Alright, it would be lovely to collaborate with you on a composition’, and he saw things like this – [on the screen of Zinovieff’s computer we can now see the interface to the Native Instruments software, Kontakt] – he would take control. I would lose any of the power I had in those days, where I could say, this is my world. Now, he would say, no – [gesturing to the staves of musical score represented on the computer screen] – this was actually his world. So I don’t see how, now, with computers, such a collaboration could really exist – unless both sides were very generous.

AU: It is difficult finding ground to collaborate these days. Especially with so much more technology. Everything is possible.

PZ: So how do you do it?

AU: Variously. With the band we have a very elaborate, ever-changing process for writing music. With my friend Will, when we’ve done things together, we tend to write separately and then work together. We have the same kind of musical vocabulary.

PZ: So how do you write separately?

AU: If we worked on a film – which we recently did – we first decided on a palette…

PZ: A palette of sounds?

AU: Yes. We had a big discussion about the sound of it before we’d even written a note. Then we decided that Will would work on that section of the palette…

PZ: So you were able to take bits of this palette.

AU: It was a way of restricting ourselves. Otherwise it would be endless what you could do. This is what I like about synthesizers and oscillators. People moan about the fact that you can’t get them in tune. I actually really like that. You can have quarter-tones. Like your DK1.

[The EMS DK1 – also known as ‘The Cricklewood’ – was a separate keyboard that could be attached to the VCS3 as an additional control interface.]

PZ: I resisted any keyboard for a long time. I did have a keyboard called ‘Squeeze Me’. Squeeze Me had 72 notes with 72 switches and each of the notes had spongy, resistive foam. You could then say, I want this touch-sensitive key to be allocated to the loudspeaker volume and I want this one to be [allocated to a different parameter]. Because in a studio like that, in the early days, there were no rules. You didn’t have a mouse and a keyboard. Now, there’s nothing – I got this [Native Instruments] Maschine thing last week, and that’s some sort of way of interfacing. And then there’s this keyboard which is very much dedicated to semitones and things. But otherwise there’s no real interface. I want something much more…

AU: More visceral.

PZ: Yes! I want something to touch. It seems absurd to have to use this Qwerty keyboard and a mouse.

AU: Were you even thinking in conventional pitch in those early pieces?

PZ: No, there wasn’t any sense of pitch.

AU: With Birtwistle or with any of the other things.

PZ: No. I think that was why Birtwistle was attracted to electronic music – because you were free: you could use exact pitch or not use it. Do you know Russell Haswell?

AU: No.

PZ: I might be going to do something with him. Some music. He came here one day, five years ago, and said would I like to write a piece – forty minutes he said. And he said, it will be paid! And I’ve just been writing continuously since. I’ve done ten pieces that have been performed. Violin pieces with Aisha [Orazbayeva] and quite a lot of Planetarium pieces. And a wonderful thing called ‘Good Morning Ludwig’ which was done in Karlsruhe with 50 speakers. You could specify – or I could specify – that the sound could come from here or there without any reference to the speakers. I believe to do away with loudspeakers will be fantastic. In a hundred years or fifty years or five. Wouldn’t it be wonderful? So you can just say that the sound comes from any point.

AU: It’s interesting, hearing you say that, because my head is still – still – in the old world. And yours is in the new world and always has been seemingly. All the things you seem to have done are thinking forward. What will be. Whereas I’m quite content – I don’t have these kind of technical aspirations.

PZ: But your music doesn’t exactly sound like Vivaldi.

AU: No. That’s right. I suppose the method is old school and – I’m slightly fearful of enormous amounts of technology. My partner, Geoff, we’re both the same, that way. Very into old analogue stuff and old methods.

PZ: But doesn’t that come back to what I was saying? There isn’t a new technology – except computers. To make music as a musician, you use your hands and feet, don’t you? That thing of touching or hitting or playing or twisting a knob and half closing your eyes as you do it, these are all tactile things which you don’t have with a computer.

AU: Unless somebody finds some kind of an interface.

PZ: So you have to change it.

The Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes by Peter Zinovieff is out now via Space Age