All portraits by Renaud de Foville

Editor’s note: an interview with band member Yahyah Chouchen had to be abandoned when the poor quality of the phone connection exacerbated language difficulties to an unmanageable degree. Later, when an email interview was requested with one of the Tunisian members of the group, it was revealed that they had quit in order to attend to family business and had been replaced for an upcoming tour by French musicians of Maghreb descent.

Earlier this decade the French post punk musicians Francois R Cambuzat and Gianna Greco – who work together as Putan Club and have backed Lydia Lunch on many occasions as part of their lengthy tenure in the worldwide underground music scene – ventured into the Djerid desert region of Tunisia to experience the indigenous Banga music performed there.

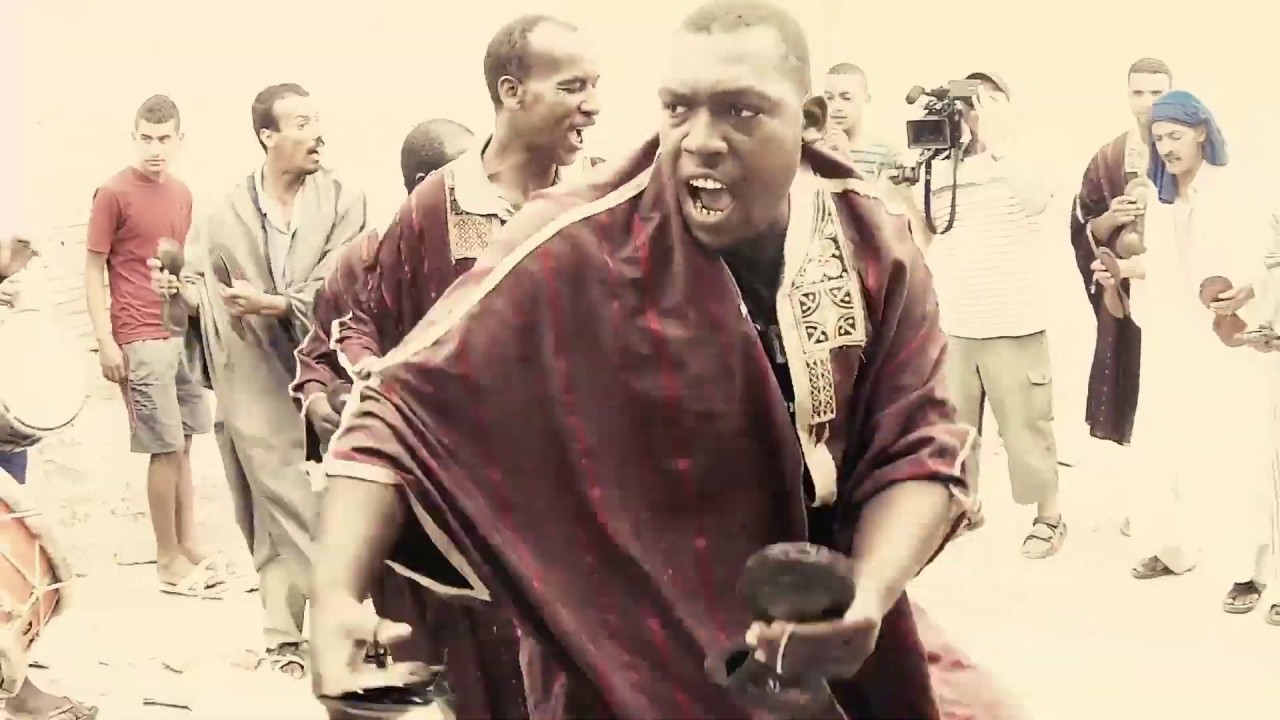

A sacred ritual comprised of songs and dances handed down through generations by the descendants of black slaves, Banga is performed by groups of varying sizes and can last for days. The music involves chant-singing and hand percussion, most notably on the distinctive tchektchekas, the tambourine-like instrument that sounds much as its onomatopoeic name suggests. Banga, which translates as "huge volume", commemorates the 13th Century slave and Sufi saint Sidi Marzuq, who was frequently aided by a collective of rûwahînes or spirit allies. The opposite of an exorcism, Banga is an adorcism, inviting a spirit to possess you and then finding ways to accommodate and accept it once this happens.

If Banga can be described as facilitating a balanced cohabitation or collaboration between human and spirit entities, then the "post-industrial ritual" of Ifriqiyya Electrique takes this a step further, as Cambuzat and Greco attempt to integrate their own post punk electronic rock music with this traditional form. Following 2017 debut album Rûwahîne, last month Glitterbeat released the second Ifriqiyya Electrique LP, Laylet el Booree, a title which translates as "Night Of The Madness", referring to the final night of the Banga ceremony, when the spirits finally take possession.

On this record and their live shows, Cambuzat (guitar, vocals, electronics) and Greco (bass, vocals) are joined by Yahya Chouchen (tchektchekas, tabla, vocals), Fatma Chebbi (tchektchekas, vocals) and Tarek Soltan (tabla, vocals). It’s a fusion immediately evident on opening track ‘Mashee Kooka’ as downtuned industrial guitar chords crash in like Ministry or Rammstein over traditional prayers to local saints, driving percussion and electronic rock beats. ‘He Eh Lalla’, a song about the female saint Lala Kandwa, opens with doomy piano chords before the chants and mixed acoustic/electro rhythms take over, creating a churning, striding soundtrack to the kind of spiritual catharsis that’s as common to a hardcore punk show as a religious rite.

Perhaps in refusing to treat Banga as "other" but instead emphasising the commonality of method and intention, Ifriqiyya Electrique rightly de-exoticise it for western audiences. A holy prayer like ‘Beesmeellah Beedeet’ retains its power and sentiment even as it becomes a killer hybrid rock track that doesn’t try to replicate traditional practices, but rather engages with those practices as a living form, refusing to treat them as an ethnic curiosity to be kept pure behind a metaphorical glass case.

With the frantic call and response of ‘Habeebee Hooa Jooani’, the heavy gothic rock of ‘Mabbrooka’ and the ten and a half minute dancefloor banger ‘Galoo Sahara Laleet El Aeed’ that fuses Banga chants to Depeche Mode-like darkwave and trippy acid techno, the music of Ifriqyya Electrique is a thing in itself. Neither post punk with world music textures nor any attempt at an authentic representation of pure Banga, it’s a genuine collaboration between French and Tunisian musicians from very different cultures, creating something new while finding exciting common ground.

Nevertheless, when I speak to Francois it’s clear he still struggles with the ethics and consequences of what started out as an innocent research project: an attempt to understand how what he calls "elevation" is achieved in different ways by traditional and non-traditional musicians around the world.

Even though this is your second album with Ifriqiyya Electrique I’d like to go back and ask you about the beginning of the whole project and your first visit out to Tunisia and the desert, your interest in the Banga ritual and how it all came about.

Francois Cambuzat: It wasn’t intended to be a band. It was more personal research for Gianna and me. We were interested in the music of elevation. We don’t much like the word trance; it’s too fancy. From when we were kids, going on stage was always a kind of enlightenment; if we felt unwell or had toothache, for instance, it would disappear. So we wanted to know how other people were doing it. Our first research was in Xinjiang in China, with the Uyghurs, because we heard when we were touring in Mongolia about the shamanism in Xinjiang. Then we heard about the Banga when we were in Tunisia, and went to see what it was about.

Some years after starting to perform the ritual – which was our original goal – it became a band when festivals like WOMAD and Roskilde wanted to have us. We thought that all this exposure and money will bring good fortune to the community, as it’s a very poor community in the middle of the desert. But we thought we will give them the choice. And after one month they said let’s do it, it will do some good for the community. They were right, because there’s a lot of racism in Tunisia against black people, and they are all black, because they are former slaves. It’s true that it’s very good for them, because we are the only Tunisian band that is touring so much, and so they are very proud of it. But yeah, I still don’t know if we were doing right or wrong.

How long did you spend living and travelling in Tunisia on this particular journey?

FC: We were touring a lot with other projects so it was for periods of a few months at a time. The longest was five months, but all in all it would be something like two or three years. Before that we read a lot, in this case Richard C Jankowsky from the Tufts University in America who studied Stambeli music. Stambeli music is the same kind of music as Banga but it’s an urban music from Tunis. That helped us a lot in not going there like a tourist, knowing nothing. The whole process took around four years actually. We were filming the whole time too. We’ve still got around 400 hours of raw material, mainly from rituals.

Was it difficult to get the trust of the community, coming in from outside?

FC: No, they were very nice and very welcoming. In Tunis I had met Amel Fargi. She’s an ethno-musicologist and she told me about the Banga and invited me to meet them the summer after. She introduced them to me and I had their trust because I was coming through her. So no, it was very easy. They are very welcoming, everybody. They are Sufi, so it’s really an open-minded society.

The music is very much grounded in Islam. A lot of the lyrics are quite sacred. I don’t know your own religious beliefs, but presumably you were coming from outside of that. Did that matter to them, and how did you feel about that?

FC: I’m completely unbiased; I don’t believe in any god. I wish I did, because I love faith. I think faith is a testimony to the weakness of the human being in front of death. It’s great to imagine that there’s something after. It’s tender. I hate religion in itself: all the power and the stuff around it. But faith is great. So no, it’s all religious songs but also the musicians are in a strange position because yes, they are Muslims, but if Daesh or IS come to Tunisia they know they will be the first ones to die, because essentially it’s a syncretism between animism and Islam. So no, that was not really an issue.

You went in there searching for a different understanding of this experience of elevation through music. What did you learn?

FC: It’s strange because I was so busy filming and imagining the thing that I never got caught in the trance or elevation state until we played for them. Then, yes: but just like with any other music, really, from jazz to flamenco to punk to whatever. So it was quite disappointing in that way. But on the other hand what I really loved and still love is that it’s a social need. It’s really creating a community and a family. People are kind to you anyway, so that was great. The humanity of it is fantastic. After that, for me, no: I never get more caught than when playing any other kind of music. But I’m always there anyway, so what is more and what is less? I don’t know actually. When we are doing it now, this theatrical Banga, because of course we are on the stage and so it’s becoming theatre, then I get caught like with any other kind of music. In the desert maybe it’s different, because we as westerners, we are in the wrong place. And after a while actually now we are not in the wrong place when we are there: we are part of the community.

On the new album did you find it easy to develop new ideas creatively beyond what you’d already done? Was it easy to find new ideas within the collaboration?

FC: When we decided to do a new album that troubled me for the whole year. Wow, so they liked it, and these guys, they want to go on with this life, so we should do something. I’ve been asking everybody: why do you like this project? Why do you like this music? And the answers were so different that in the end we said to ourselves well, let’s do what we want. But using the same procedure: that’s very important. So they are field recordings that we work with on the computer, but we respect the source material. So every acceleration, every mistake, maybe there’s one bar more here or one tempo more there, we keep everything as it was recorded on the spot there. Because then we can still learn.

On the other hand we were less afraid, because on the first record we were very concerned to be respectful. We wanted to learn, and actually it was not meant to be a record, it was just like a notebook for us. The recording came along after. From their side they also knew now what we were doing, what the computer was doing, what the guitars and bass were doing, so it was easier to be more frank and more punky somehow. Because yes, we are also coming from that; if it had been two jazz people coming there it would have been different, for sure.

On the new album you seem less apologetic about using the computer rhythms and the post-punk industrial guitar sounds. You’re blending it more naturally rather than being slightly reticent about imposing that as you maybe were originally.

FC: Yes, that was just a try-out, and that’s what we feel. I’m also a flamenco guitar player but you can’t play flamenco with the Banga. It’s impossible: they’re too loud! When they play even with four of them they are loud like hell. When we are doing the rehearsals, the first one at the beginning when we knew that the Tunisian festival wanted to have us, then we had to rehearse. So we rented a little PA and they were drowning it out, just with three of them. So you see that we anticipate this now; we have no other option. We have to put some stuff in between the tchektchekas so it’s less loud, because if not, we can’t work. When we played with them on the ritual you are under the whole, so it’s not a problem because everybody drowns out everyone else and that’s also what I like. When one guy with a tchektcheka is making mistakes there are 20 others that are playing the right thing.

When you’re playing to audiences in different countries how do they respond? Do you see them responding with any kind of elevation that’s different to what you might see at a regular punk or rock show?

FC: No, it’s the same, or more like a techno night, or a party, and that’s good. It’s making it normal somehow and I like that. What I don’t like is that we are on the stage, and that’s why on this tour that we are starting now we are playing in the audience. We’ve been working a lot on that, sonically-wise, to see how it’s possible to be playing in the audience so we can really touch the people. Because that was the thing about the first time that Ifriqyya Electrique went to Europe. We did only fancy festivals, and that’s great, but it was coming through the golden door without really meeting people. We met the crew, the organisation and the promoters, but that’s all.

It’s different doing it in the west, because it’s just a representation of it. That’s why we wanted to put the movie with us, so the people would see a bit more. That’s always been one of my frustrations, when I’ve gone to world music concerts in the past. You see these people coming from, for instance, Rajasthan and I always wanted to know more about it, more than a nice postcard on the stage. It was great music, yes, but still: you go back home and you know nothing. But I don’t know if it’s really a little bit arrogant to say that, so I don’t know if it’s a need or not. For me, it would be, so I’m acting just like I’m in the audience.

I think that is relevant. There’s a right and a wrong way maybe to approach what you might call world music, when even the term world music has an implicit colonial attitude to it.

FC: I hate it. In Africa, in Asia, in Turkey, everywhere in the world, they never call it world music. It’s music, and that’s all. And all of the business, it’s really for the western world. Glitterbeat is a great label, but we’re still on a label. There are few labels of course that are not from the west, but it’s really post-colonialism, and this I hate. It’s my main trouble with this project. I loved the first period, when we were playing there more, in the Djerid, and then when we started to do festivals in Tunisia, actually it was a bit like being in the west, because the people in Tunisia had never heard of the Banga. The first time they heard about it was with us, at the festival in Tataouine.

I think really it was a mistake, all this [laughs]. People are mixing with other people with a certain goal that is very clear: to make money, and to tour. We are lucky in that we don’t need to do that. We are touring so much with other projects so we can choose. I can really understand of course that people are looking for money and fame or whatever but that’s not our case. So I think it was a big mistake.

But as you say, you are bringing much-needed money back to the town, the community and the other musicians.

FC: It’s good for them. The last month on tour this winter, in one month they are earning what their father is earning in 43 months. So that’s great, but even that is creating problems. They are too proud of it somehow, and are being a bit arrogant with the other members of their community. We were afraid four years ago and are still really afraid that we are doing what the cowboys did: bringing a blanket infected with cholera to the Indians. It’s a bit like this.

It’s surprising if you felt that way that you decided to make a second record.

FC: We did it because they [the Tunisian musicians] asked for it. And of course we agreed because I love them. They wished that this life of going abroad and staying in four star hotels and being on the stage, having huge catering and so on would continue. They love it and they are asking for it. Actually that’s another problem: demanding and demanding, more and more and more. That’s creepy because it’s just one step before they are thinking that they are The Rolling Stones, and that’s terrible. That’s why I love this tour that we are doing now. It’s a promo tour, so it’s been staged in May then in September then in November and then again in January. And I have to explain to them everything: that we will be driving 25,000 km in a little car, the money will be less, but we will meet people. And I’m telling them that’s how it is at the beginning when you’re a band. Their first concert in Europe was Roskilde! It’s crazy, you come from the desert and then you have all this luxury and all the people are kind to you and treating you so well, of course you want to go on. Of course you wish for it to never end.

We have only one life and I’m not so greedy. I can pay my rent and I don’t really need more. I’m not here for being famous or whatever. What I really love in my personal life is that I can go to Kurdistan or Pamir and now I’m doing that. And maybe on future projects is I will publish nothing, not even an extract on YouTube. I will keep it to myself to avoid any trouble.

Laylet el Boree is out now on Glitterbeat. Ifriqiyya Electrique play live across France in 2019