It’s 10 December 1987, and onstage at The Blue Note in Columbia, Missouri, Hüsker Dü are uncharacteristically stinking up the joint. As singer/guitarist Bob Mould writes in his 2011 memoir See A Little Light, the group’s singing drummer Grant Hart is “all messed up… jonesing or trashed on booze – or both. Hüsker Dü didn’t play bad shows. But this was a terrible show, simply awful.”

Earlier that evening, Hart had returned to his hotel to discover the bottle of heroin-substitute he’d left chilling on ice in the bathroom sink had leaked away. Hart had been nursing a habit for 18 months – one he’d managed to keep a secret from Mould. But by the time he reached his drum-stool at the Blue Note later that night, he was going into withdrawal. As the singer-songwriter of half their setlist and their drummer, Hart’s bad night would prove catastrophic for the gig.

After the show, there’s a tense debrief in the dressing room. Hart confesses his addiction, and that he’s withdrawing. Bassist Greg Norton admits he’s known of Hart’s habit for some time and has withheld this information from Mould. The angered guitarist cancels the rest of the tour, and Hüsker Dü return home to Minnesota the next day, the eight-hour drive scored by brooding silence. Weeks later, Mould informs Norton and Hart that he’s leaving the band.

With that, Hüsker Dü are done, their fearsome nine-year streak of innovation and powerful songcraft ended by a shitty show in an 800-capacity venue deep in the heartlands of America. Three decades on, in 2020, Mould tells me that miserable night in Columbia was simply “the period at the end of an 18-month run-on sentence”. Hüsker Dü had been slowly falling apart for some time, he explains. “Then things reached a point where I was just, ‘This is enough’. It had to end.”

But it was a miserable end for one of the most important groups of the 1980s. Hüsker Dü had played hardcore punk of a velocity and fury that left contemporaries reeling, and later invested pop songs of rare emotional sophistication with that very same intensity. Their fateful decision in 1985 to quit SST Records for major label Warner Bros marked a key inflection point in underground rock’s incursion into the mainstream, a cultural shift that culminated early the following decade with the breakthrough success of Nirvana, whose multi-platinum Nevermind album was indebted to Hüsker Dü’s metallic, melody-spiked noise. By then, however, all that remained of the group was an enmity between the former bandmates that would endure for decades. However, if Hüsker Dü ended in recrimination, they began with a pot-smoking session in the basement of a St Paul, Minnesota record shop.

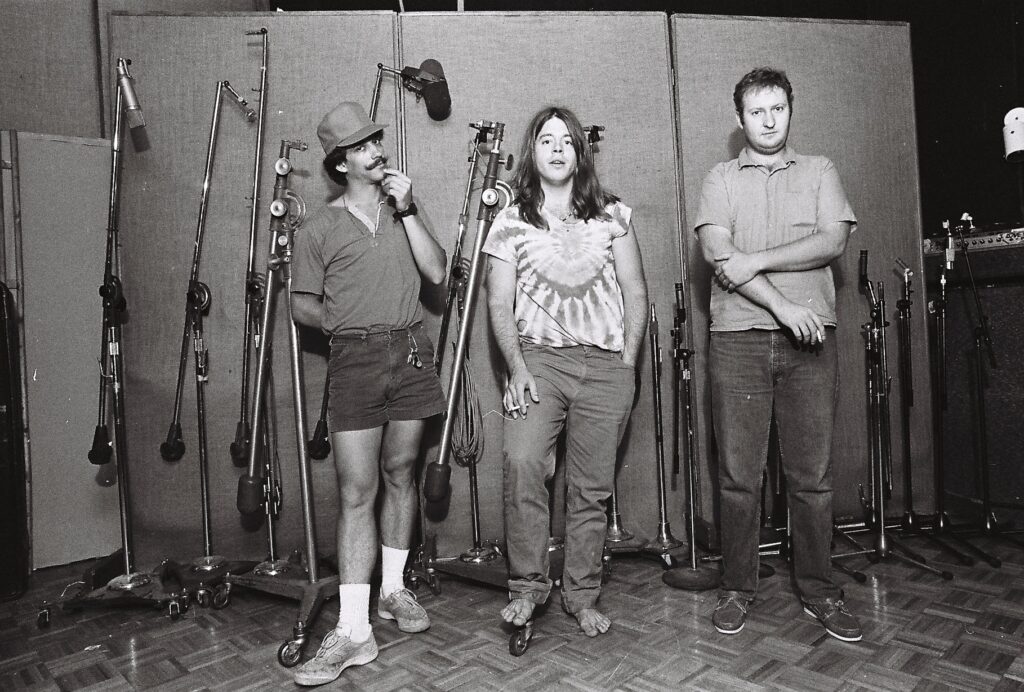

Rewind the tape a decade or so. It’s autumn 1978, and an 18-year-old refugee from rural upstate New York, newly arrived in St Paul, Minnesota, walks past a record store near the campus of Macalaster College. Enticed by the paradigm-shifting din of Pere Ubu’s The Modern Dance blaring from the doorway, Bob Mould ventures inside Cheapo Records and is greeted by long-haired, barefoot store employee Grant Hart. As Mould remembers it, their initial conversation was terse and fast-moving:

Hart: I’m a musician. I play drums.

Mould: Oh, I play guitar.

Hart: No you don’t. Do you smoke pot?

“So, we go downstairs and smoke some pot,” smiles Mould. “We walk to my dorm a block or two away and I play guitar for him. ‘Yeah, you play,’ he says. ‘My name’s Grant, we should start a band.’”

A year younger than Mould, St Paul native Grant Hart was a music obsessive and already the veteran of countless local groups. When he was 10, his older brother, a drummer, had been killed by a drunk driver. Grant inherited his brother’s drum-kit and, he would later say, his brother’s dreams and ambitions. An inveterate self-starter, Hart’s energy was infectious, and he knew of a bassist who worked at another record shop a mile or so away. “Let’s do this thing,” he told Mould.

“Grant had a wicked sense of humour,” remembers Greg Norton, the bass-player in question. “I met him in the record store where I worked, in 1978, and we became friends right away.” Born in Iowa and raised 20 minutes’ drive from Minneapolis, Norton bonded with Hart over their “voracious appetite for anything punk. Punk-rock had given me this outlet – I didn’t need to be a top-notch musician to make punk music. We started going to shows together and he brought Bob along when we went to see The Ramones support Foreigner in St Paul. I thought Bob was kind of quiet.”

Arriving at Macalester on a full underprivileged scholarship, Mould had been desperate to put distance between himself and the small farm-town he’d grown up in. “It was a very closed-minded place,” he says. “I knew I was a homosexual at that point, and there was no future for me there.” On his first weekend in St Paul, he’d scored a fake ID and took an hour-long bus-ride to The Longhorn, a CBGBs-esque dive in Minneapolis that had hosted performances by Buzzcocks, Talking Heads and the Dead Boys. The headliners that particular weekend were Twin City punk-rock heroes The Suicide Commandos.

Mould was already a punk-rock devotee. “I’d got a guitar when I was 15, to start a band where my friends and I would dress up as Kiss and cause havoc everywhere,” he says. “But I got the first Ramones album for my 16th birthday, and that changed everything. Magazines like Rock Scene depicted Aerosmith and Kiss in private jets and other fabulous situations, but when they showed The Ramones, it was Joey and Dee Dee trying to drag a PA out of Manny’s Music and load it in the van. Suddenly, this exclusive world of sex, drugs and rock & roll, which seemed very unattainable to someone like me…” He trails off. “The Ramones changed all of that in my eyes. I realised I wouldn’t mind hauling a PA in and out of a van And seeing The Suicide Commandos at the Longhorn was better than The Ramones in some arena – I could get right up front for this.”

A couple of months later, guitar in hand, Mould found himself in the basement of Northern Lights, the record store where Norton worked, standing opposite Hart and Norton. “The owner let me use the basement when it was closed,” says Norton. “Every night at 9 o’clock, we’d go downstairs and start playing and writing music.” The embryonic group practiced hard and, by the summer of 1979, after assuming a peculiar moniker derived from a popular 70s board-game import from Denmark and began playing shows in the local area. “We’re not the most professional band in the Twin Cities,” Hart confessed from the stage of The Longhorn in July 1979. “We have fun, though.”

As chronicled by Savage Young Dü, a 2017 box set of demos, singles and live recordings from their earliest days, Hüsker Dü were in permanent evolution from the off. The material performed during their first rehearsals is rough, Saints-y and Ramones-y; their debut single ‘Statues’, recorded in the summer of 1980 and self-released the following January on the group’s own Reflex imprint, was PiL-esque post punk. In the months that followed, however, their noise gathered speed and focus. This increase I n velocity and volume was a familiar story across the US, as hardcore took hold of a loose coalition of local punk scenes with their own bands, labels, venues and zines. Washington DC had Bad Brains and Minor Threat and Dischord Records; San Francisco had Dead Kennedys and Alternative Tentacles Records; Michigan had Negative Approach and The Necros and Touch & Go Records. California’s hardcore scene, meanwhile, centred around Black Flag and their SST Records imprint, both of which were key to spreading the hardcore gospel across the country. It was Black Flag who, upon discovering local bars wouldn’t book them for shows, started putting on their own gigs at community centres and VFW halls. Next, they organised punishing, low-budget tours of similar venues across the greater US, serving as inspiration and example for many who followed in their wake.

It was during such bare bones tours that crucial connections were forged between the scenes. Black Flag’s spring 1981 jaunt climaxed on 23 March with a show at Chicago’s Space Place; across town, at a club named Oz, Hüsker Dü headlined the after-show party. They went all out: Mould remembered being “out of my skull on cheap speed and beer, swinging at the air with a hammer, breaking bottles, and throwing myself into walls… trying to upstage anything Black Flag might have done at their show.” Ending with both band and venue splattered with blue paint looted from a nearby utility closet, the chaotic performance impressed Flag-leader and SST founder Greg Ginn, along with his right-hand man, Joe Carducci, who recommended Hüsker Dü connect with Mike Watt, bassist with Minutemen and honcho of New Alliance Records.

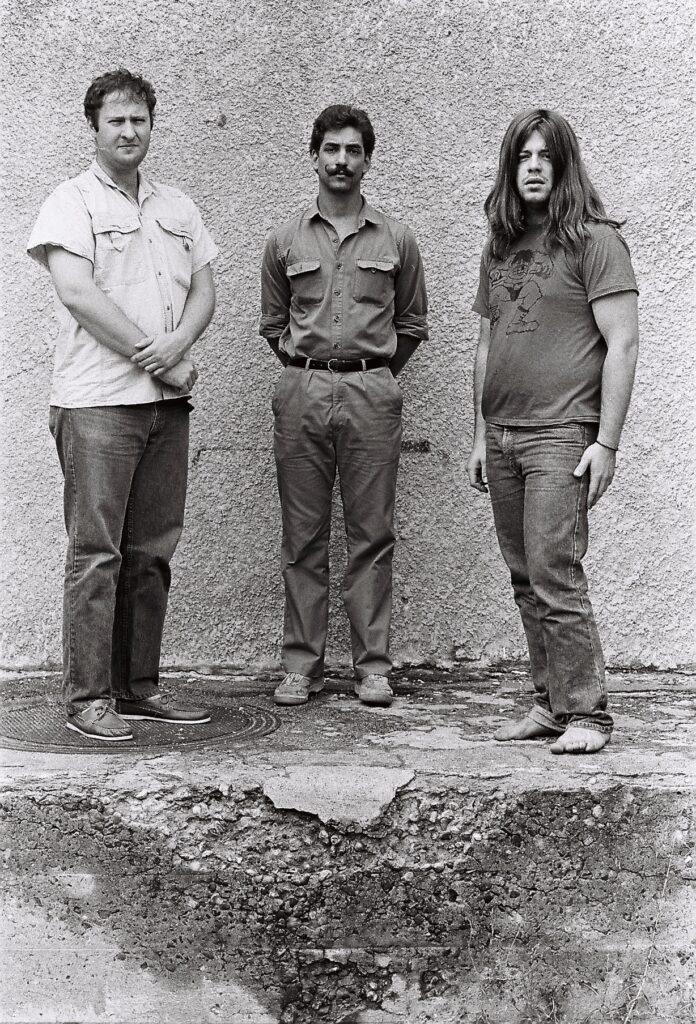

That summer, Hüsker Dü undertook their own epic tour, The Children’s Crusade (named after a failed attempt by 13th century European Christians to instal their religion in the Holy Land), which saw the trio navigate much of the US and playing alongside regional hardcore brethren such as Dead Kennedys, DOA and Millions of Dead Cops (MDC). “There were pockets around the country where kids were getting together and making great punk rock, and we were all on a similar trajectory,” says Norton. “We looked at it as this congruent revolution; it was cool to find like-minded people.”

The Children’s Crusade would prove a transformative experience for Hüsker Dü. “We picked up speed and anger across those few months,” says Mould. “When we got back to Minneapolis, I don’t think people recognised us – we’d been exposed to that really wild hardcore.” At their homecoming show, at Minneapolis’s 7th Street Entry on 15 August 1981, they performed two sets, the first of which showcased the newer, faster material they’d developed on the road. Norton’s basslines served as anchor, Hart’s drums a frenzied blur of pummel, Mould’s guitar like a flame-thrower run through a distortion pedal; the chaos was punctuated by their guttural two-part harmonies.

Engineer Steve Fjelstad taped both sets onto 4-track reel-to-reel. The results blew Mike Watt’s mind, and his New Alliance released the fevered concert album as Land Speed Record in January 1982. It’s a remarkable record: 17 songs blitz past in 26 minutes, the deranged ‘Bricklayer’ packing two verses, two choruses and a guitar solo into its 53 seconds. “When we started, we wanted to play faster than the Ramones,” says Norton. “Then we heard the Dickies and we’re like, ‘Holy shit, now we got to play faster than the Dickies!’ Land Speed Record was the last show of that summer tour. We had been out on the road since mid-June and just kept getting faster and tighter.”

Land Speed Record pushed hardcore’s brevity and velocity into the absurd, the group purposefully riding the cacophony and overload like Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz-era twin quartets jamming away on fuzz-toned guitars. But Hüsker Dü understood such extremism could quickly become a creative dead end. In the aftermath of the Children’s Crusade, they realised they actually couldn’t play any faster, that their songs could scarcely be shorter. It was time to try something else.

From the freezing Midwest, the California hardcore scene seemed like paradise, and SST Records some shining beacon atop a hill. “SST was not a label you could pigeonhole,” says Norton. “They had Minutemen, they had Saccharine Trust, they had Meat Puppets. None of the bands on SST sounded like Black Flag, except for Black Flag.”

Hüsker Dü wanted a place on the label’s roster, but SST had passed on releasing Land Speed Record, and also turned down the group’s first studio album, Everything Falls Apart. Recorded over a couple of days in the summer of 1982 at Total Access Recording in Redondo Beach, California, with SST’s gregarious in-house producer Spot at the controls, the album signalled the beginnings of an emphatic shift in Hüsker Dü’s music. While much of the 12-track, 19-minute album was still rooted in hardcore, it also contained glimmers of pop amid the brutalist melee.

“Hardcore had begun to feel constricting and dogmatic, this set of codes and markers and ideas you had to adhere to,” remembers Mould. “So we slowed down the music, a little. Melodies started peeking through. We weren’t just yelling slogans anymore – we were putting thoughts into longform. We turned away from feeling like we had to fit in.”

Hüsker Dü’s music would grow only more complex, sculpted and tuneful over the releases that followed, tempering the fury of punk by drawing inspiration from the pop gold of their childhood. For Mould, this was sacred territory. “Pop music had been everything to me. My father had a terrible temper and could be really abusive, but he would buy me boxes of discarded jukebox singles for a penny a piece. They were my toys as a kid: I listened to them day and night, memorised the label copy. They meant the world to me. I was a little broken as a kid, and music was the only thing that drowned out all the chaos I grew up around.”

As well as welcoming in melody, the group ditched any remnants of polemic and agitpop. “I was a big fan of groups like Stiff Little Fingers and Discharge, and could appreciate Crass’s ideology,” Mould says. “But it wasn’t where we wanted this vehicle to go.” Instead, Mould followed Hart’s lead and began writing more “relationship-based songs”, guided by the example of chief Buzzcock Pete Shelley, whose output taught Mould “the power of non-gender-specific love songs”.

Mould and Hart were, after all, queer artists operating within a nominally straight subculture. The few ‘out’ hardcore punks – such as Gary Floyd, singer with Dicks, and Randy ‘Biscuit’ Turner of Big Boys, both from Austin, Texas – were perceived as outliers, while scene progenitors Bad Brains were infamous for their homophobia and had left a note in Grant’s parents’ house reading ‘Die, faggots, die’, after he’d allowed them to stay there for three nights. “They were a great band,” Mould says. “But those dudes were awful.”

Mould was not yet ‘out’ and wouldn’t be for another decade. “I was still battling external political pressures, religious pressures,” he says. “I never felt ostracised in the hardcore community. It was a group of misfits, and as long as you played along with house rules and contributed in some way, you were more than welcome, regardless of what you might be doing behind closed doors. It was a very masculine, aggressive crowd, but if you look at the uniforms, they’re right out of a 70s leather bar. The paramilitary gear. The bandanas as code. I mean, come on. I saw myself as a musician who happened to be gay, and it was not imperative to express that in my work. I lamented that later, after I came out.”

In the autumn of 1983, Hüsker Dü finally became SST’s first non-west coast signing with the release of the Metal Circus mini-LP, which continued their crawl towards sophistication. Hart led the offensive, his ‘It’s Not Funny Anymore’ a scarcely veiled broadside at hardcore groupthink, while ‘Diane’ – a slow-burning, melodic piece exploring the mind of the real-life killer who had murdered Diane Edwards, a young woman Hart had been acquainted with – became a cult hit on college radio. This suggested hitherto-unimaginable potential for the group’s less-ferocious, more song-based impulses.

Their next release would hurtle full pelt towards traditional songcraft in the same breath as delivering the most savage hardcore within their discography, an ambitious double concept album. The group had signalled their ambitions to do “something bigger” in a 1983 interview with Big Black’s Steve Albini for Matter. “I don’t know what it’s going to be – we have to work that out,” Mould admitted. “But it’s going to go beyond the whole idea of ‘punk rock’ or whatever.”

Mould wasn’t merely talking a good game. The resulting album would rightly be celebrated as one of the greatest works of its era, a landmark that would help bring their subterranean scene to the attention of a mainstream that had been doing its best to ignore the ugly noise stirring in the underground.

The roots of Zen Arcade lay in a long, tedious drive along Interstate 5 to southern California the group undertook in 1983. “We were bored and looking for something to do,” says Mould, who remembers the trio spit-balling ideas “to keep ourselves sane in the van”. Together, they cooked up a narrative that updated the storytelling of Tommy and Quadrophenia for the 1980s. “We had this idea about a kid from a broken home in the Midwest who goes to Silicon Valley because wants to invent a video game called Search. His girlfriend came with him. Then she ODs. That was the premise.”

“When we were assembling the songs in the practice space,” Norton adds, “we were like, ‘I think we’ve got a rock opera here!’ It was intentional. We tracked the songs so they spelled out the narrative arc.”

Recorded in a 40-hour blur, Zen Arcade evoked the tumult of the teenaged protagonist by cycling through diverse moods and styles, including beautiful pop songs like Hart’s ‘Pink Turns To Blue’ and a 17-minute jazz-punk instrumental, ‘Reoccurring Dreams’ derived from a jam they’d play “at the end of a show to clear the room”. They embraced on-the-fly experimentalism; the mind-bending instrumental ‘Dreams Reoccurring’ was ‘Reoccurring Dreams’ played backwards and at high-speed.

The album dealt in themes of delinquency, alienation and abuse, from the domestic violence witnessed in ‘Broken Home, Broken Heart’ (“You know just how it feels / to have to cry yourself to sleep at night”), to sexual assault, as intimated on ‘Masochism World’. “I’d been sexually abused when I was a small child, outside of the home,” Mould says. “I grew up in a physically and emotionally abusive household.” It’s hard not to hear the album’s more extreme tracks – particularly its scourging second side, most of which was penned by Mould alone – as a response to those experiences. Mould says that “a handful of the really vitriolic songs” on the album are also his response to a failed early relationship with a man. “I thought it was love, but it turned out to just be two casual encounters,” he says. “I was 22 years old, and I understood my sexual preference, but not my sexual identity. That’s where the anger in songs like ‘Pride’ and ‘I’ll Never Forget You’ comes from.”

With its diversity and ambition, not to mention its resolutely non-punk musical reference points, Hart later said Zen Arcade was “a punk-rock thing to do – to release something so hippie”. Its impact would prove far-reaching and momentous. Even before a note had been recorded, the project’s grand vision inspired Minutemen to conceive their own 2LP set, Double Nickels On The Dime, released the same day as Zen Arcade: 3 July 1984. “When the Hüskers came to California to record in 1983, we barbecued for them on Cabrillo Beach and they told us about their new double concept album, Zen Arcade,” Watt says. “We thought: ‘We could do that too!’” Rolling Stone magazine raved over both albums in a joint review, David Fricke celebrating these “landmark punk works, because the chances they take and the earnest fury that drives them… are the blueprint for a brave new music”. That same issue, the group’s hometown nemeses The Replacements received a glowing review for their own dog-eared masterpiece, Let It Be.

“The review got more people to the shows, helped expand our audience and put us on the radar of the major labels,” remembers Norton. “That’s when the majors started to solicit us. One guy at a big label typed out a full page and all it said was ‘I love your band. I love your band. I love your band’.”

Fow now at least, Hüsker Dü were still happy to stay put on SST. But what a difference 365 days would make.

Greg Norton refers to 1985 as Hüsker Dü’s “miracle year”, also the title of a new 4LP box set of Hüsker Dü live recordings from that year about to be released via Numero Records. Across those twelve months, Hüsker Dü released two albums now widely regarded as classics, wrote and recorded a third, and played over 150 shows across the US and Europe. By the end of the year, they had severed relations with SST and signed to Warner Brothers.

“We were a freight train – there was no stopping us,” Norton says. “Bob and Grant were writing songs at soundcheck and in the van and playing them in the set that night. I was in awe of their songwriting ability, completely OK with being the third-best songwriter in Hüsker Dü. On tour, we’d play the album we were about to record, rather than the album that we’d just released, to get us tight enough that we could record those songs in the studio quickly.”

The group were riding the momentum of Zen Arcade’s rapturous response. But SST’s distribution system was not up to the challenge of a potential breakout hit. Norton says the label “greatly underestimated the number of copies of Zen Arcade they should press up – when we started touring the record, stores didn’t have it in stock”. “We had the momentum, and they were hanging us out to dry,” adds Mould, his frustration still apparent.

For the moment, the trio ploughed on. Their first album of 1985, New Day Rising, was by turns savage and song-focused. Hart essayed the love song from multiple angles: the heady cocktail of lust and menace that was ‘The Girl Who Lived On Heaven Hill’, and the giddy devotional ‘Books About UFOs’, driven by Hart’s jolly barrelhouse piano. Mould, meanwhile, balanced the nagging Buzzcockian simplicity of ‘I Apologise’ with ‘Celebrated Summer’, a bittersweet combination of memoir and mood-swing.

The group had wanted to produce New Day Rising themselves, but SST instead installed Spot for the sessions, which Mould spent drinking heavily and multi-tracking his guitar parts, exploring the power and articulacy of guitar distortion. The album closed with ‘Plans That I Make’, a deranged thrash across which he methodically totalled his guitar, frustration made cathartic sound. It would be Spot’s final Hüsker Dü project; Mould and Hart produced the group’s next album, Flip Your Wig, in Minneapolis over several months that spring. This album would mark another decisive step away from the roaring punk rock tumult that birthed them.

“We kept evolving towards the light, towards melody,” says Mould. “Flip Your Wig was the peak for that, in my estimation.” Indeed, Mould and Hart regarded Hüsker Dü’s fourth full-length as such a triumph they considered using it as the opening gambit of a seemingly inevitable major-label career. However, Mould says, “out of some sense of loyalty we felt we owed SST Flip Your Wig. I’ve read interviews since where Grant has said that was our worst move ever, and if we’d given Flip Your Wig to Warners we’d have been huge. And he may have been right. SST got the record that probably would have hit the jackpot.”

Flip Your Wig served as Hüsker Dü’s valedictory release for SST; by the time it hit shelves in September 1985, the group were already working on their first album for Warner Bros. “Warners were the most artist-friendly label out there,” says Norton, “and they gave us their word they’d let Hüsker Dü be Hüsker Dü, that they’d allow Bob and Grant to produce the albums in Minneapolis and Grant to continue doing the artwork. It was definitely a big step. Our lawyer told my mother that I had a real job now. We had a work ethic, and being on a major label opens doors to bigger venues and different audiences.”

“I felt bad about abandoning the independent music scene we’d helped to create and had put so much energy into,” adds Mould. “But SST was letting us down, and we felt we deserved a bigger audience, that our message was important. I wrote an op-ed for [punker-than-thou zine] Maximum Rock’n’Roll, explaining why – not burying SST, but saying, ‘We’ve got bigger goals here’. I was pretty torn about the whole thing, but collectively we made the move, and collectively we thought it was a net positive. And I think it was.” He pauses. “But none of us foresaw the pitfalls that were gonna show up.”

Candy Apple Grey was no obvious bid for mainstream acceptance, but it was one of their best. Their trademark buzzsaw pop remained prevalent, and Hart’s ‘Don’t Want To Know If You Are Lonely’ is probably their finest three minutes. The album opened, however, with what Mould describes as “one of the most difficult pieces of music we ever made”. ‘Crystal’ was a jagged account of a methamphetamine-aided mental breakdown delivered in Mould’s most deranged caterwauling yet. He would go sober the following year.

Three further tracks, meanwhile, bucked the typical Hüsker Dü blueprint. Mould fielded the solo acoustic ‘Too Far Down’, and ‘Hardly Getting Over It’, a muted strum set to metronomic drums and punctuated by a single piano note, while Hart’s ‘No Promise Have I Made’ was a straight-up piano ballad. If this softened their sound, the lyrics were unflinching: ‘Too Far Down’’s wracked, gruelling account of depression saw Mould howling that he wished he “just could die”. Where it counted, Hüsker Dü remained as hardcore as ever.

On the eve of Hüsker Dü’s first tour to promote their sixth studio album, 1987’s Warehouse: Songs And Stories, David Savoy, who’d stepped in to help out in a managerial capacity following their signing to Warners, threw himself from the Lake Street bridge, into the frozen Mississippi. Savoy’s suicide served as a grim omen for the year that would follow. If 1985 had been the miracle year, 1987 would be Hüsker Dü’s annus horribilis.

It wasn’t the fault of Warehouse: Songs And Stories, the group’s final album. There were no acoustic breathers this time, but its songs refined fresh nuance and complexity from their familiar blueprint. Mould’s ‘No Reservations’ was steeped in wintery melancholia, while his ‘Visionary’ was fuzz-punk spiked with acid; Hart’s ‘She Floated Away’ offered a flute-driven thrash-waltz, while his closing ‘You Can Live At Home Now’ refashioned the Dü’s lightning-strike din as ecstatic punk-funk. Eagle-eared listeners will note many of the double album’s 20 tracks were break-up songs.

Friction was accumulating. “Things started to get complicated after we signed to Warners,” says Norton. Hart resented how he was treated by their new bosses. “It became so divisive,” he told Gorman Bechard, filmmaker of 2013’s Every Everything: The Music, Life & Times Of Grant Hart. “The businesspeople would take Bob aside; the artistic people would take me aside. I was the clown, I was the barefoot drummer; Bob was the serious, stoic man with the plan. Little by little, all of us got corrupted by one thing or another, whether power or money or drugs.”

The ascension to the major labels had brought profound life changes, which Mould saw as “three different forces pulling in all directions, away from the core of the band. It was this slow disintegration: Greg had got married and he and his wife bought a house in the country. I’m newly sober and trying to navigate this world I’m living in where the drinking begins before soundcheck. And Grant’s drifting away from the group, towards another group of musicians who didn’t have the healthiest habits.”

Delayed by a couple of weeks as the group tried to absorb the shockwaves of Savoy’s death, the early shows of the Warehouse tour saw the group play the new album in full and in order. Soon, however, this felt like a straitjacket, redrafting the setlist to juggle Warehouse highlights with older songs, an uncharacteristic ‘greatest hits’ set. There was a dearth of new material, in part because the group weren’t spending much time together when they were off the road. But the group had pencilled in studio time in February 1988 to record a mooted third LP for Warners. “A new direction,” says Norton. “We were going to use an outside producer, we were going to record it in England with Hugh Jones, who’d worked with That Petrol Emotion. That would have been a really interesting record, had we just managed to keep it between the lines and the wheels down.”

But the tour was proving complex. “All of a sudden there was this access to unhealthy lifestyle choices,” Norton remembers. “Your mental health takes the biggest hit when you’re on the road, and some people deal with it better than others.” Hart was struggling. The previous year, he’d been misdiagnosed as HIV+, which he kept secret from his bandmates. He sensed his habit slipping out of his control. “I just had too much money than I had the wits to deal with,” he later conceded in a 1989 interview. “I started investing in my bloodstream, rather than any tangible things.”

After a show at Le Spectrum in Montreal that October, Norton walked into Hart’s hotel room and saw “what I thought was a line of coke chopped out on the table. Grant’s like, ‘Oh, don’t do that, that’s heroin’. I didn’t realise how addicted he was. He’d never intended us to know about that. I didn’t run and tell Bob. It wasn’t my job to tattle on anybody.” Norton sighs. “I always felt Grant was a genius, a really intelligent guy. Grant thought he was always smarter than the drug: ‘It’s not going to happen to me, I’m not going to get addicted, I can just do a little bit here and a little bit there’. But that’s not how addiction works.”

Hart tried to wrest control over his habit, however. The band had a series of dates booked across the Midwest in December of 1987, and he had availed himself of a bottle of synthetic heroin-substitute (not methadone, he pointedly notes in Every Everything) to see him through. Upon discovering the substitute had leaked away, Hart placed a call to a friend, to FedEx him drugs so he could “make it through the rest of the tour shining like Superman. And I should reiterate that at that point in a person’s addiction, you’re not taking the drug to fly through the air – you’re doing it so you can hold the contents of your bowels. There’s nothing more unpleasant than being around someone who is junk sick. Usually, they go to hospital. And usually, that is the point where people blow their brains out or end up with their stomach pumped because they swallow anything that they can find, to convince themselves it’s going to alleviate the junk need. I kick myself, for being vulnerable to other people’s manipulations, as well as the absence of the opioid. Shit happens.”

In the aftermath of Hüsker Dü’s split, Hart returned to SST as a solo artist. His debut album, 1989’s Intolerance, featured ‘2541’, a breakup song that invited interpretation as the ballad of Hüsker Dü; 2541 had been the address of their practice space. He was glad to be free of the band; he resented being seen as the reason they split. “The first year of my liberation from the band, my reputation was saint one day, sinner the next day, depending on who you talked to,” he says in Every Everything. “I was either newly liberated, or the guy that screwed everything up.” He followed Intolerance by forming a new group, the incredibly ill-fated Nova Mob, whose 1991 debut, amiably barmy concept album The Last Days Of Pompeii, was scuppered by the collapse of Rough Trade US shortly after its release. The following year, Nova Mob were subsequently involved in a serious car accident while touring Europe that left Hart with steel rods holding his foot together; the band broke-up while touring a self-titled second album in 1994.

Norton’s music career quickly ran aground. “When the band broke up, I lived in a small town called Red Wing, about an hour outside of the Twin Cities,” he says. “All of a sudden, I’m unemployed. I now lived far from my musician friends, so I couldn’t be, ‘Let’s start a new band’. But a good friend taught me how to cook and mentored me, and I ended up with a 15-year career in the restaurant business. And I discovered that mental health and addiction are as bad in restaurants as in the music business.” He returned to music in 2006; his most recent release is last year’s Dying To Smile, by his punk band Ultrabomb.

Mould immediately signed with Virgin Records as a solo artist, retreated to a farm in Minnesota for “a year-and-a-half of isolation, looking for something new”, and resurfaced in 1989 with Workbook, a folk-rock album centred around the volcanic, autobiographical ‘Poison Years’. “There had been people in the Twin Cities saying things I didn’t think were representative of the end of the band,” Mould says. “I felt a little bitter about that, but I held my thoughts to myself. I wanted to stay above it, but my anger and resentment went into my work a little.” Workbook proved a modest hit, but Virgin offloaded Mould after Workbook’s follow-up, 1990’s Black Sheets Of Rain, stiffed in the charts.

Redemption was imminent, however. The success of Nirvana’s Nevermind – which Mould had been on the shortlist to produce – proved a rising tide that lifted all boats, stoking interest in the music that presaged alternative rock. Warners released The Living End in 1994, a thrilling posthumous live album culled from the Warehouse tour. By this time Mould’s star was once-again ascendant: his new band Sugar, who’ve recently reformed and will play their first shows in over 30 years next year, delivered a devastating one-two punch with their 1992 debut Copper Blue and its dark-hearted, critically acclaimed follow-up Beaster. Mould was enjoying the greatest success of his career, enjoying the reflected glory of the grunge moment. “Hüsker Dü had laid the foundations for the house the Pixies built, perhaps,” he says. “Then ‘Teen Spirit’ showed up and turned it into a skyscraper.”

Not everyone in the band was so sanguine over this posthumous influence. Hart declared himself “disgusted” by an interview where Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan “said he was inspired to take the sound of Hüsker Dü one step further. I heard what they were up to and it didn’t seem like the step was made in a further direction. It was a step, but what they stepped in was not us.”

For Norton, the group’s afterlife was “bittersweet. To watch Nirvana and The Offspring and Green Day and Pixies blow up was crazy. That was the year everybody started making money. And I think it’s great they got paid and went on to have amazing careers, but… It’s like we were professional athletes before all the TV money came in and contracts exploded. We were able to have a nice income, but still, when the band broke up, I immediately needed to find a job, because I had no income. Royalties have been hit and miss ever since. But the band is way more popular today than when we broke up.”

For years, fans of Hüsker Dü – especially those too young to have seen the group play live – clamoured for a reunion. But the friction between Mould and Hart remained fierce, until 2013, when the group started work on assembling what became Savage Young Dü. “Grant and I started having more communication, because we’d have to review assets,” remembers Mould. “Once or twice a year I’d come through Minneapolis and we’d get have lunch, and it was cordial. We would joke about ‘the heat’ – like, ‘We’re getting a lot of “heat” out there, should we fake turn-it-up, see what happens?’” They ultimately chose not to even tease a reunion they knew would likely never come to fruition, focusing instead on the box set. “But we’d joke about it,” Mould smiles. “Like, ‘If people only knew we were working together…’”

In 2017, as work on the project was almost complete, Mould’s manager heard from former Babe In Toyland and Minneapolis scene anchor Lori Barbero that Hart’s health had taken a turn, and that the local scene was throwing a surprise tribute show for him, at a day’s notice. “I was in Berlin, I could not make that show,” remembers Mould. “But the day after I reached out to Grant and said, ‘I’m sorry I couldn’t be there – should we get together?’ And he said, ‘I’d love that.’ We spent a weekend together and had a really wonderful time. We were able to clear everything up, and laugh about the past, and cry a little bit about the past, too. It was tough, because Grant was having a hard time. But I think it all ended as well as it could, in terms of our relationship. We shared a lot of funny stories, a lot of really touching personal moments. That’s what you do, right? When your friends aren’t well, and you know you’re not gonna get a lot of time – you gotta make time.

“Grant passed before the box set was finished. That hurts. But Savage Young Dü is real special, and that’s what brought us back together. I’m grateful for it, that he could make the time, given what he was going through, and that I was in a position to spend time with him.”

Hüsker Dü’s 1985: The Miracle Year is out November 7 via Numero