<iframe width="100%" height="300" scrolling="no" frameborder="no"

allow="autoplay"

“In Portugal, in the places where I grew up, there was always this connotation of Macumba as something beyond reason”, explains Jonathan Uliel Saldanha when I ask him about the name of his band, the frenetic, boundary-dissolving ensemble HHY & The Macumbas. “Macumba was anything that you couldn’t explain”, he says. The term would often be used to describe a “small cluster of objects in a corner”, a sign that a malevolent individual was trying to cast a spell on someone.

The word Macumba comes from Brazil, where it refers to religious practices found across the country that originate in Africa, including the traditions of Candomblé and Umbanda. Both in Brazil and in Portugal, the term has taken on a pejorative meaning, connoting mischief, malice or witchcraft, forces associated with peripheral realms beyond the bounds of the city. In Portugal, the term also came to be infused with uneasy memories of its colonial role in both Brazil and Africa.

Through his HHY alias and his unnerving compositions with the Macumbas, Saldanha has tried to open up a sonic world steeped in the ghostly, the subterranean, the other, and to reclaim a word that “has a bad connotation”. The band’s intense concoctions of harsh brass sounds, cyclical percussion and idiosyncratic dub techniques mark them out as one of a number of pioneering groups to have emerged from the progressive, experimental music scene in Porto, Portugal’s second city. In trying to decipher the origins of these sounds, I talk to Saldanha about growing up in Porto, surveillance towers, caves, marching bands and Uganda’s music scene.

HHY & The Macumbas released their debut album, the ominous Throat Permission Cut in 2014. Saldanha acts as director of the band, which has functioned as a shifting group of friends and musicians who’ve long been active in the city’s music scene. Beheaded Totem, which you can listen to above and is released at the end of this month, is a challenging record. Full of menacing horn parts, layered over mutating percussion rhythms, it’s an album that pulls in multiple directions: low-end frequencies gravitate downwards towards the Earth, while cymbals and trumpets clatter overhead, luring the listener out of the hypnotic circularity of the percussion. Meanwhile, the brass disappears into coiling, dubbed-out echoes and reverbs. It’s an intoxicating but unstable listen, constantly threatening to veer off into demonic territories.

The Macumbas hail from the city of Porto, which sits at the northern end of Portugal. A port city facing the Atlantic, it lies around 300 kilometres away from the capital of Europe’s westernmost country. As a teenager growing up in “a trashy suburb” of the city, Saldanha quickly developed an intense appetite for music from across the globe. His obsession with rhythm began when he started studying the tabla at age 15. “My first connection with playing music was as a percussionist in a Hindustani music ensemble, playing raga music”, he explains over Skype. He admits that learning the tabla was an unusual choice for a teen at the time: “It was totally out of sync. Nobody was playing it, nobody cared about it”. But from the outset, his musical journey has followed a decidedly non-linear path. He describes Indian classical music, dub and free jazz as “the three main vectors informing my perception at that time”, citing John Coltrane’s later work, including his Ascension album, and Indian sitar music by the likes of Nikhil Banerjee as strong influences.

And that was before he heard jungle. He describes the “visceral feeling of rhythm and sound” that he got from dub and jazz leading him towards the frenzied soundsystem culture of jungle. He and his friends promoted “most of the jungle raves in the late 90s”, he says. Many of his friends were “MCs in the hip hop scene, but we all shared this love of jungle”. It’s a love which seems to have shaped his approach to making music every since. “Even if I listen to a percussion piece by Xenakis, I still think about jungle”.

Over a slightly crackly, distorted Skype connection, Saldanha’s synapses seem to be constantly fizzing. He’s good-humoured and curious, and happy to tell me about the “very hectic and intense period” in Porto’s music scene that HHY & The Macumbas first emerged out of during the early 2000s. Pivotal to this was a collective of musicians, artists and producers going under the name SOOPA, which Saldanha co-founded in 1999. The collective put on shows and events, acting as a meeting point for multi-disciplinary artists from across the city. He describes it as “this blend of musicians coming from metal, from hip hop” and from other genres. “We were blending it together very fast, because we are a bit cut from the rest of Europe. With the [economic] crisis and the cuts, nobody was coming here. We were just inventing our own variations of styles. This bubble was really helpful for us, for making very specific combinations of sounds.”

As such, the music of the Macumbas is filtered through both global and hyper-local influences. “There’s a strong marching band tradition here”, he explains, which guided the direction of Beheaded Totem. His attraction to brass sounds emerged early on in his life, when, under the advice of his trumpet tutor (who went on to become one of the central members of the Macumbas), he dropped out of jazz school and formed a “free jazz marching band” called The Freaks, a kind of early iteration of the Macumbas. Part of the Macumbas’ sonic repertoire draws on the military energy inherent in marching bands. He notes how the world’s oldest known marching bands are attributed to soldiers of the Ottoman empire, who began “imprinting music as a power tool for fear.” This “dramatic military effect was interesting for me”, he adds, becoming a conduit through which to explore the “primal relation to loud sound” that he was discovering in himself.

Part of the reason the Macumbas’ sound is so tough to define is because their music emerges out of an attempt to create their very own form of “traditional music”. As he puts it: “I was always very interested in this idea that we could make our own traditional music, the traditional music of this group of friends. There’s a group of five rhythms that we use, with different tempos, different accentuations. Kind of a signature. These rhythms became part of our sonic world”.

The desire to create this hyper-specific sonic culture comes from Saldanha’s discomfort at trying to place his music within a ‘Portuguese’ cultural tradition. “I grew up listening to dub and tabla music, so I cannot say that I relate to a clear Portuguese path, whatever that means” he says. For him, the idea of trying to create a style of music “attached to a national narrative is very strange”, having grown up listening to music from across the world and “watching movies that were made on the other side of the Atlantic.” There’s an almost paradoxical intention at play here: the band draws on an open-minded, inclusive and internationalist appreciation for global music cultures. Yet at the same time, they desire to create a set of rhythms that “serve a community effect”, linked to a very particular location.

This unusual approach to composition is replicated in the live arena, where the Macumbas have developed a reputation for fierce shows. When the band plays live, Saldanha takes on the role of producer: “I usually play the mixer” he says. “I create echoes of what’s happening. Also, I control an external ghost drummer, in the sense that I take parts of all the percussionists and I blend it into new sounds. I take the snare from the drummer, a conga from the percussionist, a trigger from another and from those inputs I create an extra drummer that I control myself.”

The concept of a ghost drummer seems to encapsulate the way Saldanha works. His whole approach to making music is informed by an almost maniacal interest in unusual acoustic spaces and non-traditional uses of sound. He became “obsessed with acoustic resonances and working in spaces that have weird acoustics”, following a visit to Teufelsberg in Berlin. He was standing and singing inside one of its large dome structures and felt that his “voice was louder outside my skull than inside, like I was dubbing my own voice.” Teufelsberg (literally Devil’s Mountain in English) is an artificial hill in West Berlin, built over the remains of an unfinished Nazi military college which became a surveillance tower used by the US National Security Agency during the Cold War. This aspect of the site fascinated him: being there wasn’t an “ecstatic religious experience but more of a biological, toxic experience of reality.”

This interest in unusual acoustic environments led to a long-standing fascination with tunnels, and a creative partnership with Jerusalem-born, New York-based musician Raz Mesinai (also known as Badawi). In the mid 2010’s he joined Mesinai during his explorations of underground tunnels in New York, where the pair met “all these mole people, people living underground in metro tunnels”. On returning to Porto, Saldanha began investigating the city’s ancient system of aqueducts, tunnels and caves. These explorations led to the film Tunnel Vision, in 2016, a sci-fi movie produced by Mesinai and created in the caves and cavities around Porto.

The possibilities presented by tunnels and other underground spaces inform all of Saldanha’s work. When I ask if there is a connection between his interest in subterranean realms and his predilection for manipulating bass frequencies, he answers in the affirmative. “For sure”, he answers. Bass frequencies are like “the flesh talking. The resonance of your bones and your flesh is moving without your meaning. And this is super powerful. You’re being animated by a presence. It’s a massive body that you don’t see but you feel”. He sees the whole underground realm as “an organism, a massive soundsystem below us that we can connect to.” These explorations in acoustics and in underground spaces led to Saldanha creating what he’s referred to the as the ‘Skull-Cave-Echo effect’, by exploring the acoustic properties of caves, and creating dub effects from their particular resonances.

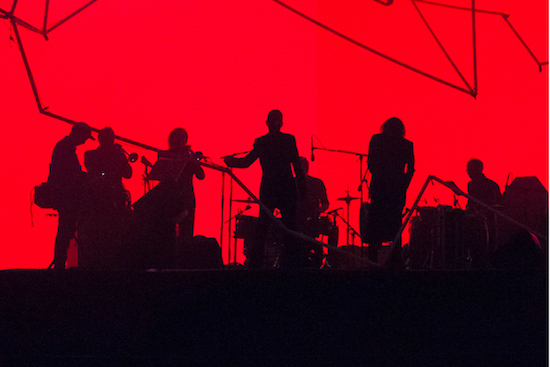

Photograph by Isabel Correia

After having been at the forefront of Porto’s local experimental music scene for so long, how does he view the artistic activity happening in the city today? Porto has changed significantly, he says: “Now we’re living in a very touristic, EuroDisney kind of place. This was a very fast evolution. I think it’s the tendency for many cities in the world." Porto’s changing cultural landscape has brought greater possibilities to musicians and artists in the city, though he feels a bit distant from this now. “There’s so much stuff happening that I really don’t feel like organising anything. I’m more focused on my own work. I’m a bit detached from the groove of the city.”

As to the current health of the music scene in Portugal in general, he sees good things happening. Porto has “a couple of different collectives that are doing great stuff. Some of them were very active in the SOOPA collective. There’s something called Sonoscopia. It’s a place for experimental improvised music.” He also mentions the importance of Portuguese festivals such as OUT.FEST and Milhões de Festa, as well as the pivotal role of Príncipe Discos, the Lisbon-based record label that is home to producers such as DJ Marfox, DJ Nigga Fox and Niagara, artists producing electronic music heavily influenced by the cultures of the city’s African communities, particularly those from Angola, Cape Verde and São Tome and Príncipe.

Feeling a little detached from Porto’s current scene hasn’t diminished his creative output in the slightest. His relentless work ethic means that he’s continually developing new concepts and ideas. The SOOPA collective has morphed into what he now describes as a production house focused on larger projects such as theatre shows and installations – “stuff that takes six months to be built”. Alongside his prodigious talents as a musician, he studied sculpture at Faculdade Belas Artes in Porto and currently spends much of his time working on audio-visual installations. When I ask what drives him to want to explore visuals and space alongside sound, he replies that it’s a case of discovering the form the artwork wants to take. “If it’s movement or light, I just follow the form. It’s not that I want to do an exhibition or an installation. There’s this dialogue with ideas – they define themselves."

Recently, he’s been working “inside a black box” in one of Porto’s theatres, working on a piece that’s due out in November. “It’s a video and performance piece”, he explains. “It’s a court where there’s a judgement of an object”. Participants try to “interpret the object through looking at it and touching it. I have a group of four deaf teenagers that are looking at the image and interpreting it through gesture. Then the gesture is interpreted into sound by a engineer”. It’s a project about exploring the leaps of meaning between objects, gesture, eyes and sound.

As to the Macumbas’ next project, he tells me he’s just returned from a month and a half spent in Uganda, collaborating with local musicians from Kampala, as well as from neighbouring Congo. He performed at Nyege Nyege, one of East Africa’s most important music festivals. “I went there and it was one of the most intense things I’ve done in my life. It changed my biology. I collaborated with amazing people and we developed a new project called HHY & The Kampala Unit, that’s like another vision of HHY & the Macumbas, but through a Uganda-driven reality.” All of which points towards the fact that one of the most creative imaginations in contemporary Portuguese art and music shows no signs of slowing down.

HHY And The Macumbas’ Beheaded Totem is released on 28 September on House of Mythology