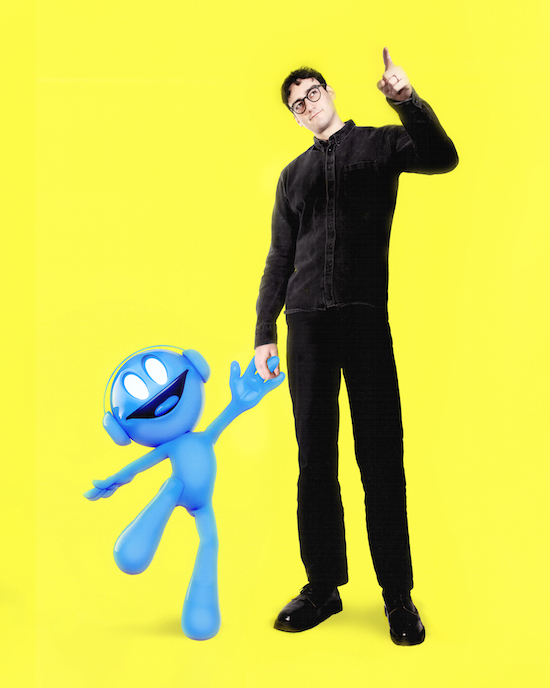

Europe was still in lockdown when the classically trained British producer Danny L Harle unleashed his ambitious multimedia project Harlecore into cyberspace. Comprising a conceptual album of hyper-energetic contemporary renditions of 90s & 00s dance music, the virtual club experience Club Harlecore and an interdisciplinary live act, what had started as a platform for his musical passions suddenly became a necessity.

It all began in 2017 with a Harlecore night in London, which was followed by tours in the UK, Europe and the US. “The idea was to create a channel for the music that I love and produce, but it expanded and became a living culture,” says Harle, who has been lauded as the most chart-friendly PC Music affiliate.

In the early 2010s, he reunited with his former schoolmate A. G. Cook, making music as Dux Content – their track ‘Like You’ (2013) would become one PC Music’s early outputs. His debut solo single ‘Broken Flowers’ came out that same summer, but he only achieved mainstream recognition in 2016 after it was re-released on Columbia Records. The success opened many doors and he became a prolific collaborator, producing and remixing for celebrities like Charli XCX, Carly Rae Jepsen and Nile Rodgers among others. In the meantime, he attracted a dedicated legion of fans with ecstatic singles like ‘1UL’ – you can encounter the in-jokes huge and huge Danny in almost any online debate regarding him.

As a youngster he was drawn towards complex music styles to an almost fetishistic extent, but he realised he should be more honest with himself. “I became obsessed with sounds that make me feel good.” He learnt about genres like Eurodance, happy hardcore, hard trance, gabber and mákina, which heavily inform Harlecore, in isolation by osmosis. “I was never part of any scene and always had a headphoney relationship with music.”

Club Harlecore was initially meant only as a vehicle to give his music context. “I had to think of a way in which I could present it and realised there used to be all these multi-room superclubs. Why wouldn’t I build a dream environment for this music,” Harle says. He associates its pyramidal structure with euphoria and transcendence, “like an ancient ritual site that existed before it was turned into a club”.

It actually resembles 90s superclubs from my vicinity like Piramida in Pula, Croatia, and Cocoricò in Riccione, Italy. Divided into four floors for his separate DJ personas – Euphoria Stadium for DJ Danny (himself), Boing’s Bounce Room for MC Boing (collab with Lil Data), Ocean’s Floor for DJ Ocean (collab with Caroline Polachek) and Mayhem’s Dungeon for DJ Mayhem (collab with Hudson Mohawke) – it is designed as a utopian environment through which the user moves based on their mood.

Profusely saccharine and hypnotically iridescent, his music deftly fuses hardcore immediacy with a cartoonish pop sensibility. Everything about Harlecore is exaggerated, bombastic, hyper – no wonder I cannot get the video for Scooter’s blatantly euphoric masterpiece ‘Hyper Hyper’ (1994) out of my head. It simply looks and sounds like the forefather of Club Harlecore.

What was your main obsession in the early days of PC Music?

Danny Harle: The connection between the extreme avantgarde and extreme pop music. I’ve always loved that in popular culture, films like Cats or Tenet, high risk, big budget, nuts. At the time, nobody was interested in what synths or production techniques pop producers were using. Using their language to make an experimental song with the same pop sounds, that’s what fascinated me.

I was interested in the most authentically fake pop music and I realised that you get all these extremes in pop music in far greater amounts and more skilfully executed than in contemporary classical music. It’s interesting how sometimes the commercial sphere can be more avant garde than the supposed avant garde.

Which are the qualities that define the genres found on Harlecore?

DH: For me, it’s always the melodic and chordal sensibility that unites the whole thing. I don’t care about drums and sound design. They’re in service of the song, the voice, the melody. All I want is to feel emotions. The mantra of Harlecore is music that sounds the way I feel. It’s still an unsolved mystery why some sounds make us feel a certain way without any lyrics telling us what’s happening. I love drowning in that mystery without thinking about it too much.

What kind of feedback do you get from people regarding their experience of Harlecore?

DH: Something that blew me away was the Discord server Club Harlecord, which was made for listening parties for the playlists that I was making. It was fan-made and the best social platform for Harlecore. Another emotional moment for me was when they had a Harlecore listening party. Not only it was compartmentalised exactly like the club, but it also had a cloak room, a hall of fame, their own artwork and they even had DJ Mayhem checking in coats. People also harvested the 3D models from the website and made their own Harlecore fan art, which is something I’ve never seen done ever before in music, just video games. That’s a lot more than I could’ve ever wanted.

I recently discovered on Reddit that somebody wrote a master thesis on Harlecore.

DH: It’s titled Club Harlecore As An Exit Route and it’s focused on the escapist element of the whole thing, which is definitely a key feature of the project and the culture it derives from. The way it’s inspired people to do various things, I find it very touching.

Do you think the concept of guilty pleasure still matters in 2022?

DH: People often come to me for some sort of release of all their guilty pleasures, because I represent this total lack of any kind of guilt for shamelessly liking this music, which actually comes from very serious and interesting traditions. For example, Vengaboys is traceable back to mákina and all that Italo dance stuff. It has its origins in these trance, hard dance communities… I absorbed that music in my childhood, but didn’t really know where it came from. I think the idea of the guilty pleasure is losing its edge for the fact that the underground doesn’t exist in the old fashioned sense and indie doesn’t mean what it used to. Now an artist that’s supposedly “underground” comes out with a single that can literally be the number 1 single next week. If an artist truly came from the underground, everybody would love them, and didn’t have any social media, there would be major A&Rs at their gig the next day. It’s the same with selling out, things are constantly shifting and I don’t think people really know what to be guilty about anymore. Where do we put all the shame and guilt?

How did your Harlecore premiere at Unsound Festival go?

DH: It was too much to take in. There were so many moving parts to that show. I was wearing a motion capture suit underneath my jacket and what I was doing DJ Danny or DJ Mayhem were doing on the screen. The funny thing was that I think I said something that was quite unclear to the Unsound lighting team – they are fantastic! – and when it started they put two spotlights on me and Sam Rolfes, who took care of visuals. I went to the stage manager and asked him if they could please turn them off as I couldn’t see the screen. They turned off everything, the lasers too, for basically the entire show. 20 minutes before the end I was like, “Where are all the fucking lights and lasers?” And then finally, it went full blast just for the grand finale. People thought it was an intentional move. It was extra impactful. Watching videos from the show, I realised that many of Sam’s visuals are set in a live environment. The lighting from his visuals was club lighting and it provided the visuals for the show from inside the actual Club Harlecore. It was literally the club that we were dancing “in” for the vast majority of the show. I find that very satisfying as an idea.

How did people react?

DH: I’ve never had a proper crowd response to any of these songs before, but they were really going for it, which took me by surprise. I could only see a sort of undulating mass of people as I was very concentrated on sorting out the set because all my movements were being motion captured. After the show, I realised that it actually had had an impact on people. They crowded the front of the stage to take photos and many told me how meaningful the album was to them, specifically in the period of its release. It’s funny how the whole concept was thought of far before [the pandemic] happened.

Do you consider your project somewhat clairvoyant since it coincided with the birth of virtual clubs?

DH: It was very weird, because the pandemic forced everybody into these fantastical styles of entertainment that are all based in your head, playing video games and staring at screens. Maybe that circumstance allowed more people to experience the project in the way that was intended.

Do you like to see yourself in the position of a father figure to a new generation of artists?

DH: I’m literally a dad so I’m very happy to take on the role of the father figure. I’m equal parts amazed and honoured that anybody liked my music, let alone was influenced by it.

What’s it like going against the grain?

DH: When you’re onto something new, you’re made to feel like an outsider for the first few years, and then, suddenly, instead of clearing rooms you start filling them. I know Sophie had this experience as well early on. She was often booed off stage. I think one of her first gigs was in a small pub playing her stuff from the Numbers period. Basically nobody looked at her playing until one person who actually did went right to her face and went like that [raises middle finger]. If there isn’t an established culture to sort of respond to music in a certain way, people often react aggressively because they take it very seriously.

Did something similar also happen to you?

DH: I remember feeling different in the early days and paying for that as well. The amount of DJs sets I’ve done and cleared the room… I remember I played a night in Brussels with many respectable techno artists. There was this Berghainy industrial techno atmosphere and, as much as I respect it, I don’t have any such music. I think I first played ‘Fly On The Wings Of Love’ until I completely just stopped the vibe and was like, “Ok, this is what’s happening now”, but luckily everybody was up for that tone change and I didn’t clear the room. That was an example of how it actually went really well. But in Poland I was thrown off stage because I was booked to play a weird tech house stage. It wasn’t even the fault of the other DJs, they were just like, “Mate, what are you doing?”, and I was like, “I don’t know, this is Sega Bodega’s remix of Freestyler and I really like it”. And then an enormous Polish guy who didn’t even make eye contact with me bashed me out of the way. He just took my USB out and didn’t even eject it. When someone means business they do that. I guess my music isn’t really vibey in that generic, housey kind of way. It’s quite engaging, it demands your attention.

What’s your advice to younger people?

DH: If there’s something that you really like and it’s causing disruption, then it often means that you’re onto a new thing and people find it uncomfortable. They’re actually quite scared by the fact that it’s the sound of things moving forward.

Any plans for this year?

DH: At Unsound it was a collaboration with Sam Rolfes, but it’s clear that it worked fantastically well. It set a standard for the Harlecore live show and it’ll probably expand. Besides, some of the remixes that are coming out are honestly the best remixes I’ve ever heard in my life for any project. I also have Danny L Harle stuff coming up. The songs were written a year and a half ago, but during the Harlecore preparations I’ve been using my time in between for my next album, which is another thing that’s gonna be a pure expression of what I want to listen to.