“Bishop’s Castle: where ambition goes to die,” says Haress guitarist David Hand with a laugh. He’s recounting some words that were said to him when he and Haress lead singer and guitarist Elizabeth Still moved to the Shropshire market town 17 years ago. At the 2021 census, the population of the town was recorded at 1,843 residents in 868 households, though despite the low concentration of people – approximately seven per hectare – Bishop’s Castle boasts a thriving artistic community, bolstered by Still and Hand who are very involved in the local scene, curating festivals such as Sin Eater in nearby Rattling and all-dayers in the town. Ambition wouldn’t be the right word to cover this but maybe activity is.

The core constituent members of Haress – pronounced hares rather than heiress – are at the Acid Horse festival in Pewsey when I meet them. We’re adjacent to a barge and a white horse figure carved into the Wiltshire hillside that overlooks the site. Having just played a magnificent set, we’re now under an awning, and it seems wholly appropriate to be interviewing the duo in a field given how much their music seems to rise up from the soil. Luke Turner, on these very pages, described their music as “blissed-out psychedelia [that’s] not quite pastoral – there’s nothing twee about these unwinding grooves.”

“That meant a lot when I read that,” enthuses Still. “It’s not meant to be pretty in that way”.

Where they’re normally located sits on the periphery of Wales, a land border that they describe as a “jigsaw”, meaning you can leave and return to England several times on any given day. Beyond the steep facade of the town, you’ll find plenty of burnt out ravers in the hills on the eternal quest to re-find their depleted serotonin. New album Skylarks performs the neat trick of being as psychedelic as it is rural. So how important is location to Haress’ creative process?

“I think from my point of view, sometimes what I write comes directly from what I’ve done or where I’ve been or whatever,” says Still. “It’s not particularly about the location of where we are in Shropshire, but more about the present of where you are. That can even mean sitting on a kitchen stool in the house and looking out of the window or thinking about something else entirely when there’s loads going on around you.”

“Yeah, I can’t quite imagine doing a noise band living where we are,” chips in Hand. “It definitely shapes what you do day-to-day with all the time you spend walking around in fields. That’s definitely going to influence you.”

“I don’t feel like I want to go louder,” adds Still. “I feel like I want to go deeper and broader, rather than projecting out. It’s like you want to get right into the ground and the shape of the hills.” She mimes digging into the soil as she’s speaking.

The band’s third studio album was partly inspired by an external source: Benjamin Myers’ novel The Gallows Pole, published in 2017. The story was picked up on another 2025 record, Mark Pritchard and Thom Yorke’s Tall Tales, particularly the track ‘The Men Who Dance In Stag’s Heads’ where Yorke drops down to deliver some uncharacteristically gruff baritone. What is it about this story of eighteenth century coin-clippers from the Upper Calder Valley that resonates?

“We both read it and really enjoyed it,” shrugs Still. “We just started playing our guitars as we were talking about it, and then we started playing this riff. And then we could imagine [the character] King David on the back of a cart going into York. So it just became a response to it.”

“Yeah, it just started out as a conversation with a badly played riff on two acoustic guitars,” says Hand, “and then we were both a bit fired up. We got on Instagram and sent a message to Ben Myers, and said: ‘This is your sound when you make The Gallows Pole into a film’, because this was before the series. ‘When it gets made into a film, here’s your soundtrack’. And then I’m thinking: ‘Oh shit, should we have sent that?’ Then he got straight back, and was like: ‘Ah, damn, too late’. It’s already being made.’”

Skylarks certainly feels widescreen cinematic regardless, augmenting stealthily over four largely instrumental tracks, creating a sense of tension that is released when a small collective begins to sing the only words on the album: “Far above the skylark sings / And beats the air with joyful wings / Till all the sky with music rings / At high noon of the day.”

Did they use a proper choir or was it more an ad hoc arrangement? “I mean, yeah, it was very ad hoc,” says Hand, with a laugh. “We just went: ‘Do you want to sing on this?’ There was no asking, ‘Can anyone sing?’”

“We just basically went around people we knew and asked them,” says Still. “There’s only about ten people. We recorded it in the public hall in Bishop’s Castle which is crazy resonant as well. We recorded it downstairs and upstairs, and then we engineered it with some magical jiggery-pokery.” There’s little in the way of overdubs on Skylarks, an album that was well rehearsed before they took it to a studio in Nottingham. Whether playing as a duo with just guitars and some gadgets, or playing with the band, Haress are well-versed in immersing themselves in the euclidean rhythms of folk. “We just maybe added some double bass and guitar,” says Still. “We were both bass players before we were guitar players, so there’s definitely a rhythmic aspect whether there are drums in use or not. There’s a repetitive nature and a cyclical nature to it.”

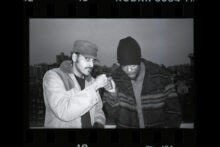

At Acid Horse, Haress play Skylarks in full, with the addition of some unexpected hip hop. Still drops bars from ‘Method Man’ from Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). It’s a welcome juxtaposition that inspires an ecstatic response from the audience. As the pair rightly point out, folk and hip hop come from a similar place, with the Wu just playing the contemporary folk music of Staten Island if you will. “We normally perform a song called ‘Somerset Girls’ that Liz wrote years ago,” reveals Hand, “And we usually do that at the end of the set. We played it at Supersonic and it made people cry, so it’s kind of funny that anyone expecting that got ‘Method Man’ instead.”

The group, which on record includes David Smyth on drums and Chris Summerlin on guitar, had intended to include ‘Somerset Girls’ on Skylarks, but it became apparent that less was more regarding the trajectory of the album. “We left it off in the end,” says Hand, “because it just didn’t feel like it was needed.” The experimental and the austere are balanced finely in the work of Haress, where bells, melodicas and Shruti boxes are incorporated into the playing. On the recording I thought I heard a waterphone at the outset, though it turned out to be Still manually pressing a bell into the bridge of the guitar. That inclination towards the experimental took its time to become accepted, but the good folk of Bishop’s Castle are coming around to the idea. “I remember playing a few gigs when we first came there,” says Still, “and people were sort of saying: ‘I think I like it but I’m not quite sure what I’m listening to’. We’ve definitely made a breakthrough since then. Or we’ve just worn them down, basically.”