Bethesda is a slate town of 5,000 people in north-west Wales ripe for romanticisation – or that’s before you hack through its layers. It’s a stunning point between the mountains, rivers, lakes and woodlands, not far from the wild Irish Sea. Between 1900 and 1903 it was also the location of Streic Fawr (The Great Strike), one the longest industrial disputes in British history, which took place in response to exploitation, hazardous working conditions and very little pay in local slate quarries.

It’s also where Gwen Siôn’s music-loving mum brought her up as a single parent in the 2000s, blasting jungle and drum and bass at home because she couldn’t go raving. This was a love her daughter would inherit, going to early dubstep parties in disused tunnels in her teens as she started to explore the world outside her door, sonically as well as physically. “Nature and the environment are so much a part of my work because you can’t escape it in a place like this,” Gwen explains over Zoom.

Her new work, Llwch y Llechi, is premiered next month: a live audio-visual project exploring connections between music, landscape, tradition and ritual, created with ten musicians from the National Orchestra of Wales and Côr y Penrhyn [her local quarrymen’s choir]. It’s being staged by Llais, the Wales Millennium Centre’s five-day-long festival exploring the voice, which is part of the wider, month-long Cardiff Music City Festival, celebrating innovation in sound across genres through gigs, immersive art and installations throughout the whole city.

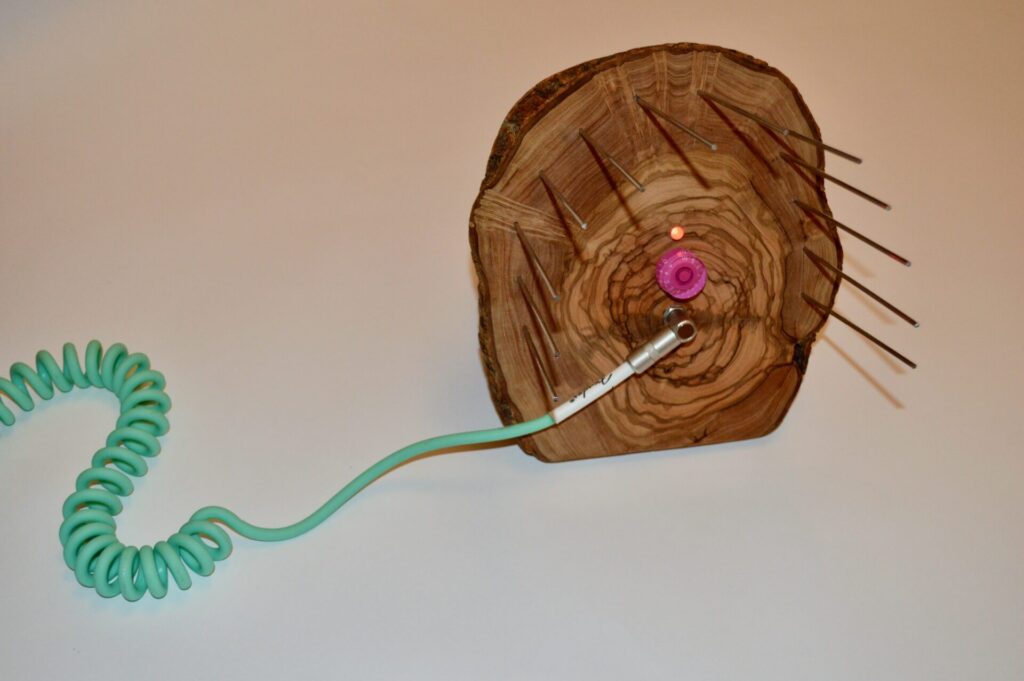

Siôn’s work combines electronics that transform biodata from the landscape into musical notation and textures, and instruments she’s made herself from raw materials – for this project from slate harps and log violins that can be plucked, bowed or used as percussion. The places about which Siôn makes art resonate through their own materials, an effect she amplifies with contact mics and effects.

Siôn didn’t start out as a musician, though, “although my mum did have a piano at home that I messed about on”. As a child, she’d play with tape machines, recording her voice for hours, making nascent field recordings, a practice she’d delve into more deeply as she got older. In her early 20s, she made electronic music as part of a local collective outside her day job working for an environmental charity. “I was also into sculpture and sound art and installations, but I didn’t know how to put them all together.”

Then at 25, she quit her job, applied to Central St Martins to do a degree in fine art, and got in studying the XD pathway (2D is drawing or painting or photography, 3D could be moving image or performance, XD is “when you work across disciplines – when you don’t fit in!”). But then the pandemic came. In the beginning, she was at home with her mum and threw herself into nature in that strange, sun-blasted silent spring. She noticed how a lack of human interventions in the landscape made room for nature to flourish.

In later lockdowns, she was stuck living in her cheap digs in Watford and shielding, not able to go into university, so she started building small instruments from things she had to hand. The Shadowboard, for instance, is a 12-note polyphonic analogue synthesiser made with old food tins, wood offcuts, takeaway boxes and light-dependent resistors, and can be played entirely without touch.

Siôn also spent time in local woodlands that were soon to be destroyed for the HS2 project, field recording and collecting material to work with. “That time was a bit of like a light bulb moment for me,” she explains; “I love being tactile, making things, so using the instrument-building as another layer of incorporating a specific place or landscape into the sound made so much sense.” She also loves the way the sculptural element of handmade instruments can visually communicate a sense of place. “It’s all about translating the natural world in different ways to have an impact on people.”

Sion’s resulting piece from that time, HS2 Ghostlands, aimed to show how music could be a starting point for a conversation around what was happening to that environment. She made “some kind of sound archive of the woodlands before they were destroyed”, creating instruments from fallen branches. She realised she could build activism into her work and be political – it was only a matter of time before she took that approach to the place she called home. Siôn spent time researching the sociopolitical history of Bethesda’s quarries, and the ongoing tension between what she defines as the natural and the industrial. “In quarrying communities, the quarries represent a lot of things – death, poverty, strikes, lockouts, really high levels of air pollution and respiratory diseases. Bethesda is literally in the shadow of the quarry which is quite literally carved out of the mountain. You can feel the weight of it and everything it represents, but still so many people feel slate is special, like a part of your identity.”

When she works with slate, she has to wet it so that the tools don’t overheat, “and there’s something about the smell that reminds me of rainy days – it’s so evocative of home.” Côr y Penrhyn, a choir that formed around the workplace in the 19th century, also play a central role in her piece. At times, they sing actual words from Siôn’s research, and at others, their voices offer textures and sounds.

We talk about the raw, gutsy melancholia of Welsh men singing together, and how singing aids social cohesion and physical wellbeing in a culture affected by the after-effects of fallen industries. “Singing’s a really strong bonding thing, not just for its emotional impact, but it probably has a positive impact too on the use of the breath and the use of the body.” Siôn uses their voices in “quite ghostly ways”, the men sometimes singing different words on top of each other, meshing these sounds with others from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales performers, as well as environmental sounds and sounds of the weather.

The project’s been a mad learning curve, she says – she’s not classically trained but has had to notate everything on staves. “It’s been worth it. The whole point of this project for me was trying to bring together three disparate, separate musical worlds and just see what happens.” We chat about the project’s mashing together of different expectations of class: the choir representing both working men and the e aspirational society of chapel; the orchestra a more rarefied culture; field recordings and electronics the glow of the art gallery, the club or the dancefloor.

Siôn thinks of all sounds as the layers, she says, none prioritised over the other. “It’s just an experiment at the end of the day. I wanted to see what would happen when you bring in very different musical worlds and try and create some kind of fusion because the spaces in between things, that’s where I think exciting things happen.”

After Llwch y Llechi, Siôn is working on Atlantis 2050, a project combining sound, moving images and environmental data on rising sea levels in some of the UK’s most affected areas at risk of being underwater by 2050, and Earth and Sky, a commission from Opera North to create a sound walk up on the moors of Brontë Country for Bradford City of Culture 2025, using geolocation technology so sounds are triggered in headphones.

But for now, she’s at home, steeped in sound and music, in the most granular detail. “In Wales, sound is such an embedded part of Welsh culture, something that you could dig into in layers and layers and layers,” she says. Her considered, ambitious, compositions suggest looking at the extracted side of a mountain, seeing the strata, and feeling the impact of humans on the landscape through the centuries, resonating today, and for all time.

Llwch a Llechi (Dust and Slate) by Gwen Siôn is premiering at Llais 2024 on Sun 13 October at 3.30pm at Wales Millennium Centre‘s Weston Studio. For more information go here.