Photo by Eva Vermandel

“I tend not to censor myself,” Gina Birch – post punk icon and founding member of The Raincoats – tells tQ from her home in London, reflecting on her 45 year career. “If something excites me, I just go with it and I don’t worry about what anyone else thinks,” she smiles, punk’s anarchistic spirit still running strongly through her veins. Birch is discussing her new, debut solo album, I Play My Bass Loud – a work made up of thrilling new songs as well as several older compositions mined from her extensive musical vaults. It’s being released on Jack White’s Third Man Records next month. “The album is like a map of my musical, political and artistic life,” Birch explains. “It’s a personal diary using sounds and lyrics, full of fun, rage and storytelling.”

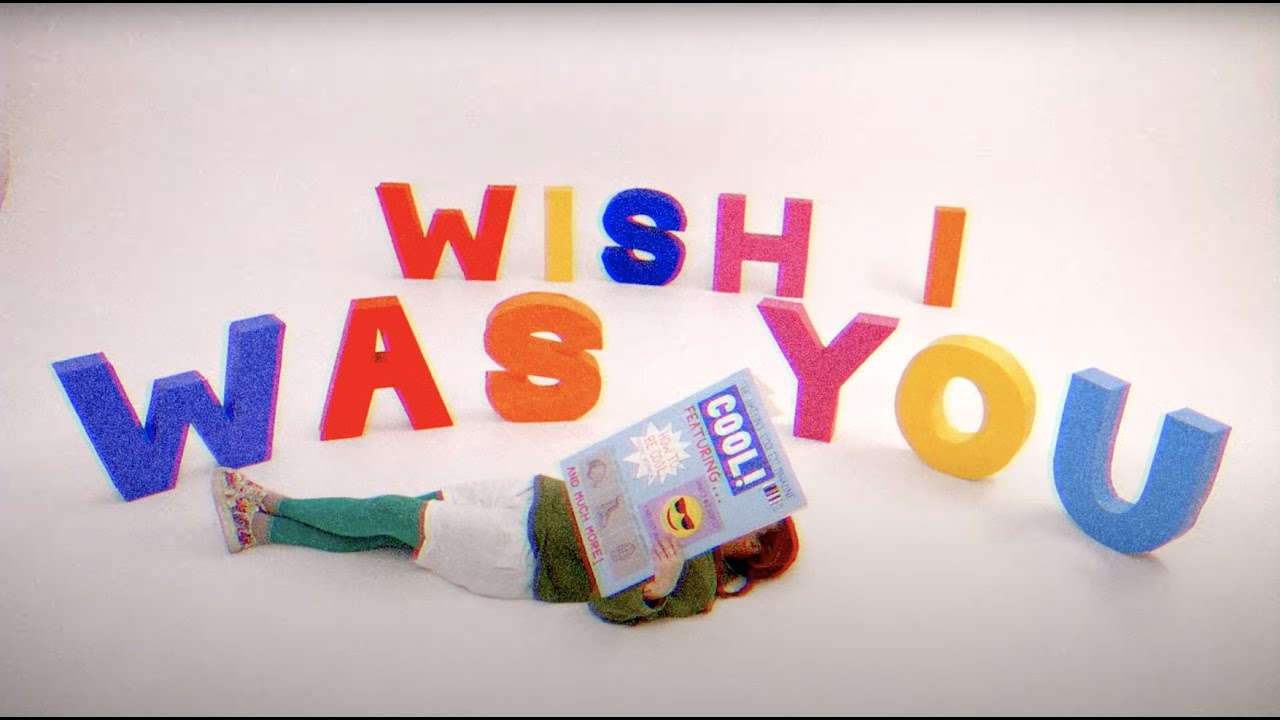

The album’s thundering lead single, ‘Wish I Was You’ mirrors this statement of intent. A fun, poppy grunge number with swashes of shoegaze, the new song was written with her co-producer on the album, Killing Joke’s Youth, and features guitar from one of her biggest fans Thurston Moore. Like many songs on the album, it is often deeply personal and emotive. “I used to wish I was you / now you wish you were me… So many brilliant people I wished I could be… Now I’m happy with me,” she sings on a track about finally finding peace within herself after years of self doubt. “I think imposter syndrome probably affects women more than men and certainly, when I was taking my first foray into the music world in the 1970s, I was always thinking: ‘Do I belong here?’” Birch explains. “I certainly feel more at ease now – but you know, it never completely disappears.”

Birch doesn’t just belong in music, she helped build the foundations for the riot grrrl and grunge generation that followed her own, inspiring many young women to make music along the way. Forming The Raincoats with Ana da Silva while studying at Hornsey College of Art in 1977, they were one of the first bands to sign with Rough Trade – their experimental, post punk leanings fitting well with the label’s innovative ethos. Three albums and a cult fanbase later, they were cited by the likes of Bikini Kill, Sonic Youth and Beat Happening as an influence, as well as Kurt Cobain who wrote about his love of the band in the touching sleeve notes on Nirvana’s 1992 compilation album, Incesticide. He invited them to open for him on tour in 1994 (he died before the tour took place) and in his journal, he listed their debut album as one of his favourites of all time.

Cobain had felt imposter syndrome too when he went to seek out Birch’s bandmate da Silva who was working at an antique shop when they were on hiatus in the early 90s. “He went into where Ana was working but she didn’t know who he was,” Birch explains. “We had to go and find his music and listen to it and then we were like: ‘Fuck! He’s brilliant!’” In his sleeve notes, Cobain recalled the encounter: “I politely introduced myself with a fever-red face and explained the reason for my intrusion. I left feeling like a dork, like she probably thought my band was tacky.” Da Silva and Birch later sent Cobain a signed album and a note shortly after his visit.

“There was also a touching letter from Ana,” Cobain recalled in his sleeve notes. “It made me happier than playing in front of thousands of people each night, rock-god idolisation from fans, music industry plankton kissing my ass, and the million dollars I made last year. It was one of the few really important things that I’ve been blessed with since becoming an untouchable boy genius.” Birch says Cobain’s interest in them led to a reunion and a fourth album being made, several years after The Raincoats took a break and Birch’s new band Dorothy took flight. “He was a true kind of brilliant soul and spirit,” she remembers. “We were just all so terribly sad when we heard the news about his death. It was so traumatic. We were really looking forward to the tour and just so touched he asked us.”

Birch in 1978, photo by Jerzy Koznik

Birch and Cobain shared a love of Sex Pistols and The Slits too: the two bands that led Birch to start making music in the seventies. Birch remembers seeing a “life changing” Sex Pistols gig and then, soon after The Slits, something she describes as “a revelation.”

“Up until seeing The Slits, it never occurred to me to form a band,” Birch continues. “I had no inclination to form a band either, but once I saw them and I saw that kind of rebellion, energy and excitement – and just the way those songs spoke to me in a way that no other song had spoken to me before so directly – well, it spoke to my sense of adventure, rebellion and mischief. It was everything a young woman could want from music at that time. It was a eureka moment.”

Perhaps most importantly, the gig convinced Birch that there was a place for women in punk in what was then still a male-dominated movement.

When The Raincoats eventually took to the stage, they felt lightyears ahead of their contemporaries both stylistically and musically: they were one of the first DIY bands, for example, learning to play their instruments in real-time on stage. It didn’t matter that they weren’t the best musicians to begin with, what mattered more to them was the expression of the self – of letting the audience in to see their mistakes, observe their process. Of particular note too was the way the band leaned into their femininity – in style, lyrical content and co-operation. Their lyrics led you to the great feminists of the past and present, while the dynamic between their first all female line-up on stage was devoid of hierarchy and ego. While many female punk fashions of the day were more masculinised, Birch recalls wearing spotty dresses and hairslides on stage and the band wanting to celebrate being women. “We weren’t afraid to show [our femininity], despite the boys-y crowd we found ourselves in,” Birch explains. “We showed a whole other side of our feminine psyche [during performances]… and it felt important to do that…we were proud to be female and different. We sang in aCapella harmonies, we were anti the-strutting-male-rock-star image and we let our feelings show. We were showing a different side of a female sensibility, one unhindered by cultural mores and that was unrecognised at the time.”

One of Birch’s housemates was worried about how they’d be received by largely all-male audiences, but it wasn’t something that worried Birch or da Silva at all. “Back then, as a woman, if you looked vulnerable, well – you were likely to get attacked,” Birch explains, saying her housemate was worried they’d be heckled or have things thrown at them on stage because of how different they were. “If you were a young girl standing on stage in those days, you were expected to look a certain way, to look pretty, to sound pretty. We looked great, but we didn’t look how they would like us to look and we didn’t sound like they would like us to sound. But we were doing our own thing out there… I suppose we inspired people and our bit of bravery was our ability to stand there and take it. If they couldn’t accept that this is who we were and what we were doing, we felt that they’re the ones with the problem, not us.”

Birch was no stranger to toxic masculinity. Long before the #MeToo movement, Birch, who is also an acclaimed artist and filmmaker, says she was “doing a lot of painting about sexual abuse” based on the toxic behaviours she saw in the 70s and 80s. “I think I was interested in speaking a lot about the unspoken, and lots of young women were coerced into sexual relationships that they didn’t want back then.” Birch remembers her time as a waitress trying to make ends meet in between making music when “lots of weird and awful things happened” to her and her friends, things she says were “actually quite hard to say out loud.” She continues: “I couldn’t speak them or sing them, so I tried to paint them instead.”

At the time, she says such behaviour towards women was so “normalised”, many just accepted it was a part of life. Birch said getting a chance to make music or go to art college felt so radical compared to her mother’s generation, that it was often brushed aside. “Certainly, women of my age – we didn’t even see it as rape or sexual assault back then. We saw it as a hazard of life – just as one of those things, which of course it absolutely wasn’t…we were just grateful to not be attending the secretarial colleges [our] mothers went to – attending art college or making music was still, at the time, a radical act…there were so many rules for women of my mother’s age that we just didn’t have to follow and being able to form a band was an extraordinary and brilliant thing.”

Photo by Eva Vermandel

Birch’s new album is full of feminist anthems that explore women’s experiences in a patriarchal society. ‘Feminist Song’, a spiritual sister to the riot grrrl movement, catalogues her anger against continuing misogyny. “Damn all those people putting women down / Yes there are women in positions of power, but so many more in chains in drudgery – tortured, undermined, undervalued, raped, abused, written out of history,” she speaks on the track, her rage palpable. On the cutting ‘I Will Never Wear Stilettos’ she recalls a woman “tripping along” in high heels and tells her: “I’m not saying the city is a war zone / But can you run in them? Sometimes you’ve just gotta run, run, run…” Birch growls: “I’ll never wear stilettos…why should I?” on a track that illustrates the continued fragility of women’s safety amid the male gaze, decades on from when she first experienced such behaviours herself.

Birch says that when assembling the album, the injustices still facing women around the world felt present in her mind. Birch included a song she’d written about Russian art punks Pussy Riot on the album (the song has been freshly remixed by Raincoats bandmate da Silva for an upcoming release), saying they proved a big inspiration. “I think I was and am very moved by what they did – the bravery of getting up in that church and singing that seemingly blasphemous stuff, knowing the consequences and then facing the consequences with such fortitude,” she explains, referring to their 2012 protest where they performed ‘A Punk Prayer’ at Moscow’s Cathedral Of Christ The Savior. The event brought attention to Russia’s human right abuses but landed the group in prison.

“They stood side-by-side with what riot grrrl was all about,” Birch continues. “They were an inspiration to me – they were talking to me, to women [everywhere] about the major issues we are dealing with in the present day. Seeing young women being that brave…it’s very touching and heartfelt. They’re very smart, amazing young women.”

Birch says the song ‘I Am Rage’ on the album was another inspired partly by women’s rights. “When I first wrote that, I was actually coming down from a burning, boiling rage,” she explains, saying the words to the song tumbled out in a stream-of-consciousness flurry, and ended up like a long poem on the page. It was very personal to begin with, but then changed direction when she reflected the many atrocities that were happening to women around the world – from Sarah Everard’s brutal murder at the hands of serving Metropolitan Police Officer Wayne Couzens, to the decimation of women’s rights in Afghanistan.

“I was just so angry. I started to write down what I was actually feeling, without [censor]. I was thinking about all the various things that were happening to women around the world and it was just all so awful.” After taking the song to Youth in the studio, Birch eventually decided to keep the anger in the song more general so that live, she can adapt the song to whatever new issue might spark anger in the future. “I mean, I don’t even know where I’d begin with the world right now,” Birch says of the state of women’s rights and politics across the world today. “I don’t think they’ll be a shortage of subjects, sadly. But these things are always worth talking about and dealing with them through song or art is a way to process the horror… It’s just the screws for women still seem to get tighter and tighter and sometimes, I don’t know how to deal with that beyond art and music… usually images come to me first, words and music later on.”

For Birch, painting has always existed alongside her music. She recently had a celebrated solo exhibition of her art and last year, illustrated a book of Sharon Van Etten’s lyrics. Art, she says, is “a bit more forgiving” than the music world for women “of a certain age” like herself, citing the work of Patti Smith and Yoko Ono to illustrate her point. “The art world is slightly less obsessed with youth, unlike music,” she says, pointing to how many women are cast aside in music once they pass thirty.

Time, ageing and mortality were touchstones for the album too after Birch found herself facing several cancer diagnoses in recent years, including breast and lymph node cancer. Most recently, she was told she had a melanoma on her leg and needed a lymph node removed in order to survive. When her surgeon pointed out where her scar would be following a procedure, Birch laughed. It was exactly opposite another scar on her other leg that she got at birth: she was one of the first babies in Britain to receive multiple blood transfusions and survive the process. “The symmetry of it all was quite funny,” Birch laughs. “I had a scar on one leg from being hours old and soon another, now, at my age. There was a curious circularity to it all.”

Birch turned to art once more to help her make sense of her diagnoses and started work on a naked self portrait of herself – one with all her scars on show. “I didn’t think, ‘oh how terrible that I have all these scars’”, she explains. “Because life brings all those scars not in a bad or sad way, but just in a living-life way. There are loads of nude women painted for their beauty, their gorgeous round bellies, their breasts or whatever and I thought it would be a fun and radical thing to paint a naked woman, myself, with these scars because most women are life-worn, we live, we exist and we become who we are – and we’re proud of it…forget the male gaze.” Birch displayed the painting in a group show at writer, artist and poet Sophie Parkin’s The Stash gallery in 2022. “I’m not ashamed of the scars, I’m not hanging my head and looking down at my body in abject horror. My body is my body: if it functions well then I’m bloody happy.”

Birch in 1978, photo by Shirley O’Loughlin

In 2016, Birch was having chemotherapy every four weeks. On treatment weeks she would feel “pretty awful,” but on the weeks off she was “okay and ready to work,” often heading straight into her studio to paint – and wanting to make each day count. “I feel incredibly lucky to have survived but it also [made] me think: use your days. Use every day. Don’t fuck about too much,” she laughs. “I would paint furiously on those two weeks off from treatment,” she smiles. “It was a really productive time for me, painting then. Sometimes I think I look back on it with slightly rose-tinted spectacles and I don’t remember how awful it was. It took a year out of my life but it was a creative time, against the odds and something like this really does transport you somewhere.”

What came out of the studio was a plethora of what Birch describes as “angry paintings” about the abuse of women, mirroring many themes on her album. Time also played a part again. She was thinking back to her teenage years and the abuses she and her friends experienced in their youth. “I was delving into political territory and also painting these large in-your-face pictures of the abuse of women: it was revenge for the many injustices that my girlfriends and I went through as teenagers,” Birch says.

She continues: “I’d been looking at a lot of paintings in the National Gallery where things happen to women – things like The Rape Of The Sabine Women. They’re all beautifully painted, the women are all kind of semi-naked and they’re all experiencing some abuse. There’s a potential male gaze kind of enjoyment in seeing these women treated this way, and it got me thinking about some of the things that happened to me and my friends and presenting these themes from a female perspective… I wanted to do it differently.”

In between painting furiously, Birch did allow herself more calm time to think too, especially in the hours between treatment when she felt frustrated she was “doing nothing.” She remembered reading something by Patti Smith that helped her make sense of these moments. Smith talked about her mother “staring into space” when she, as a child, would ask her what she was thinking about. Her mother would reply “nothing” and only years later did Smith understand when she too was thinking about that same nothing. “It became a part of my manifesto. Don’t worry, get bored, do nothing, just sit there if you need to. Just zone out because in fact, while all that’s happening, there is a lot going on that you are kind of unaware of. There’s a kind of processing that you’re doing and…I realised that when the ideas started to come. I started to forgive myself for having these days.”

Photo by Eva Vermandel

Birch’s album is in many ways an extension of this studio time. It’s her most fierce, angry, political, personal and layer-stripping work to date perhaps best illustrated by album standout song ‘And Then It Happened’, which Birch describes as “a letter to herself”. “I stopped trying, almost stopped caring”, she sings, on a song about losing purpose amid the state of the world and her illness. “I’d been trying for so long, slogging, pushing, hoping, dreaming. One day I stopped caring and on and on it went,” she emotively sings until revealing she was “Swept on a breeze” and found purpose again – in politics, in feminism, in art and in punk.

She’s now arrived at one of the most creatively fertile periods in her career. As well as her first solo exhibition last year (many of the paintings she did during her chemotherapy ended up on display at London’s Gallery 46 in an exhibition curated by Duovision and Sean McClusky), her album arrives next month, plus she has plans to finish a long-awaited documentary film about The Raincoats. She’s also keen to use her voice to continue to speak out about injustice and to channel, once again, the rebellious, anarchistic spirit of punk.

“People think that because I’m much older now, I’m a different person from the punk I used to be,” she smiles. “But that’s not the case at all. I still carry that same spirit with me now. I feel that person’s either beside me or inside me. It’s still there and I think it always will be.” Like the album’s title track, she still has lots of plans to keep playing her bass too as she gets ready for her upcoming spring tour. “I just want to open my big bay window upstairs and blast it out some more,” she laughs. “I will always play it, and always play my bass loud.”

Gina Birch’s debut solo album I Play My Bass Loud is released on February 24 via Third Man