It became clear on 9 June that jokes about the far right’s inability to organise public shows of force had actually been misplaced. As the rupturing images of dry-salted thugs battering coppers with scaffolding poles in the middle of Whitehall and alcohol-cured blokes giving jaunty Nazi salutes outside Downing Street started to stack up on rolling news, it was impossible not to feel instantaneous micro-nostalgia for the laughable state of street fascism of just three years earlier. And therein lay part of the problem.

Summer 2015 presented us with National Action’s White Man March – a 50-weak bunch of modern dressing up box fash. They made the mistake of choosing Liverpool as the location for an ill-conceived parade of white power. While no doubt nasty, potentially dangerous little shits in real life, on the day they looked as if they’d crab-walked straight out of a soundcloud rap or nu-metal video. They were vastly outranked, outclassed and outnumbered by seasoned left wing counter protesters and ended up humbly sitting out the ire of the anti-fascists in the left luggage section of Lime Street Station with only Merseyside’s thin blue line preventing them from receiving a proper hiding. It was well funny. Why not mock them?

Slightly less amusing though was the follow up demo organised by the North West Infidels (who were emboldened by a firm of Polish football hooligans) that culminated in several people, including an elderly black woman, getting injured and racially harassed. And then again last Summer, another far right march kicked off violently outside of the main train station, with 12 arrests and several injured. Merseyside showed its true unflappable colours once more: as counter protesters pushed the neo-nazis back up to Lime Street, some wag blasted out the Benny Hill Show-soundtracking ‘Yakkety Yak’ on a portable soundsystem. There were fewer people laughing this time though.

Fast forward to this month. Over 15,000 swarmed near the Mother Of All Parliaments – their ranks made up of EDL, Football Lads Alliance, UKIP stragglers and new player, the For Britain Movement – with self-professed English patriots giving Heil Hitler salutes. It was now time to admit that the liberal rejoinder to ‘just laugh’ was the only joke left still ringing clear. There’s a strong argument to be made that all the sad trombone guffawing at the White Man March from hundreds of thousands of observers assembled on the social media sidelines managed to achieve was to make a successful public show of force an absolute necessity for England’s far right. A show of force that has now been comfortably demonstrated.

What a difference three years makes. The most obvious contrast between National Action and the many admirers of Tommy Robinson, bar numbers, can probably be seen in their style of dress. It’s the difference between the feverish daydream of a racist spicehead nupped out in front of a YouTube playlist of drill promos and ISIS beheading videos and… utter normalcy. There’s no othering this year’s lot – some of these people look like they could have stepped out of my local Wetherspoons in Hackney, from the pub where I worked in Hertfordshire, from the warehouse where I worked in in Essex, from the dole queue I joined in St Helens, from the dole office I worked out of in Manchester, from a large family gathering even. You’ve spent the last decade or so reading books about this? Well now it’s here. This particular disaster isn’t something that’s probably on the cards. It’s already begun. We’re several stages deep into it right now.

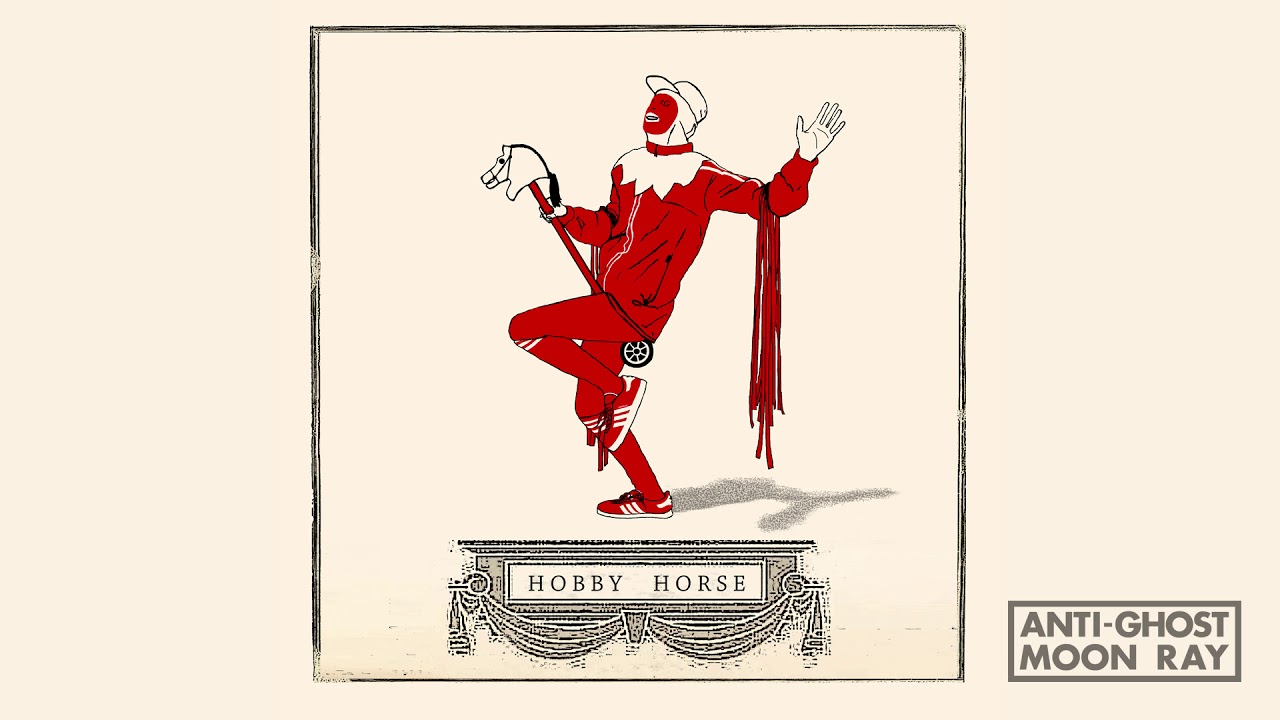

As the violence was unfolding in town, Elizabeth Bernholz, the musician behind Gazelle Twin, was shooting a video four miles away. Her vision for ‘Hobby Horse’, the lead single from her new album Pastoral, seemed to be a dramatic encapsulation of the day’s main news event, which in turn felt like just a single pyroclastic bomb from a much larger, global eruption of horror. The promo film features a modern folk devil, a “hench, thug character in St George’s Cross colours, a pawn on the modern political chessboard”. The symbolism of it couldn’t have been more appropriate – even if she was totally unaware of what was happening across town.

Bernholz is on Skype, speaking to me from her ‘den’, the spare box room/makeshift studio of the house she shares with musician husband Jez (part of the live line-up of Gazelle Twin) and their two-year-old child Ezra. They have lived for two years in this corner of rural Leicestershire which she describes as “all flat… in the middle of fields and industrial estates really. When I’m out I see dog walkers and that’s it”.

Speaking about the day of the shoot she says: “I hadn’t been into London for ages… On the way in we drove past the neatly wrapped shell of Grenfell Tower. We were stuck in slow moving traffic surrounded by drifts of sunburnt Brits everywhere. I was feeling dizzy from the heat and I was in full costume. I can’t help wondering if the oxygen level in London is lower than where I live. It was like how I imagine being at high-altitude feels, except for the burning sensation in the throat from the pollution.”

When she arrived at the set in Camden, she met the actor Richard who was playing the thug. She says he was “lovely… the total opposite in character to how he looks”. He had worked with the same director before, playing pretty much the same role and claimed that there is a lot of “that kind of work” available for actors at the moment in Britain. After he was handed an ill-fitting Adidas T-shirt and shorts to put on and some LED lights for his eyes, it was time to start filming.

She says: “One minute we were chatting about working in the arts while eating macaroons and the next minute he was pacing and grunting like he was about to bottle someone. I was leading him along on a rope around his neck, hidden under a cloak like the elephant man.”

All day it seemed like the shoot was feeding back into real life, or vice versa: “After it was over, when we tried to leave, Camden Town tube was closed temporarily to prevent overcrowding on the platforms. In hindsight I wonder if it was related to what was going on in the middle of town… I found myself with my manager Steve in the centre of a huge crowd of people, all with that drinking-all-day-in-the-sun vibe. I get it, having lived in Brighton for many years, but after a bit of distance from it, it suddenly felt very grim and very threatening somehow.

“I looked down at a tiny little girl at knee level who was scared of all of these bellowing blokes and cackling women and just felt my soul drop away. It was definitely one of those moments where you just want to shut off completely. I guess that’s how most people survive London at times, and life in general.”

I ask her about the new and unusual costume that she was wearing. (And it is unusual even by her own standards – the outfit for the cover of Unflesh was a grubby blue-hoodie, a wig and freshly butchered meat.) Initially she answers by way of a tangent: “It’s creepy. There are so many St George’s flags everywhere at the moment… I never used to notice it. But since the Brexit thing you can see people glancing at each other: ‘Are you? Yeah? I am too…’ There’s been this build up of confidence. It’s starting to spread out, adding up to bigger numbers. It’s getting serious.

“The costume has all of that feeling in mind but it also embodies the figure of the court jester. It’s a period of history I keep on being reminded of. The era of mediaeval torture. The era of the music of the courts. It’s the combination of that and weird English traditions such as Morris dancing. This was an instance of me instigating my own rudimentary version of Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies. My oblique strategy is that I think to myself, ‘What’s the least cool thing I can include in this project?’ and then include it. This time one of the things was Morris dancing.” [And her second rudimentary oblique strategy? To play her school recorder extensively on the album.]

The idea for the costume began to take shape during the last Gazelle Twin project, Kingdom Come – a multimedia stage performance based on JG Ballard’s final novel which debuted in March 2016. The show, which opened while Bernholz was heavily pregnant, featured two vocalists (Natalie Sharp, The Lone Taxidermist, and Stuart Warwick) wearing costumes that led many to believe they were actually Elizabeth and husband Jez. The proxy vocalists sang while running on treadmills in front of specially commissioned films of shopping malls and underground car parks, shot by Chris Turner and Tash Tung. The novel itself features a tribal gang of hooligans in a London suburb, centred round the vast Metro Centre shopping mall and sports facility, who start brutally attacking immigrants. She says that even though this aspect of the novel didn’t end up as part of the Kingdom Come performance, what really stuck with her after reading the book, was this idea of a uniform, based round a bastardized St George’s Cross design, which the thugs adopted: “I had this lingering image of these carbon copy groups going round smashing stuff up which is not at all a stretch of the imagination when you think about it.

“But then, I didn’t want there to be any clear references to the English flag or to Morris dancing on Pastoral. It is to do with those things but not 100% about them. It’s a mixture of things, including a bit of Punch and Judy as well. I wanted someone who was familiar and sneering and demonic and jeering. I wanted it to feel like a scarecrow figure.”

It?

She laughs: “Yes. It’s very important that you say ‘it’ not ‘she’.”

After the interview I sit poring over the portrait of the Jester figure, trying to figure out if I’ve missed something and after five minutes it clicks: it’s wearing Adidas Gazelles, the classic football casual trainer from the mid-80s.

The only bit of Elizabeth Bernholz you can actually see on the cover of ‘Hobby Horse’ bar her hands, are her pearly whites. She reveals little of herself but a wide Cheshire cat grin. It’s symbolic of the lusty vigor that the album resonates with; it stands in marked contrast to the pallor of illness and physical discomfort that wreathed Unflesh four years earlier. At first, this big, beaming, Colgate-formulated smile seemed like the most incongruous aspect of a very incongruous visual incarnation… until I heard the record that is. Then it made total sense. Her grin reminded me of something smart David Foster Wallace said about the joyousness of the evil figures that habituate David Lynch films. In a feature written during the filming of Lost Highway, the writer raised the gleeful, dynamic, supposedly ambiguous way with which the director portrayed his most wicked characters: “The bad guys in Lynch movies are always exultant, orgasmic, most fully present at their evilest moments and this in turn is because they are not only actuated by evil but are literally inspired: they have yielded themselves up to a darkness way bigger than one person.”

Pastoral is a deeply affecting state of the nation address populated by modern folk devils and the devils that modern folk are becoming. But this isn’t the mockery of the liberal bourgeois who maintain a position of elite moral superiority by observing from an elevated position, the distance allowing them the luxury of dividing folk up into good and bad. Rather this is a closer quarters, more dispassionate view of evil as a dynamic force that transcends humanity – a force that contracts and expands, losing and gaining people as it does. In this less palatable but far more realistic scenario there are very few authentically good and bad people, merely people who will do good or bad things when subject to certain conditions – sometimes, terrifyingly, acting en masse. Without moralist exposition what we are left with is a neutral presentation of evil in all of its power and vitality. Presented here in such forensic vividness, it may help the bewildered voice – the voice pealing with laughter three years ago but now bleating weakly, ‘How did this happen?’ – it may help that voice find the grain of an answer.

When I ask about the jagged, infectious energy of the album and her huge grin on the front cover, Bernholz says: “Making the album has been a four year process. I have spent the time since Unflesh touring, moving house, making a baby and then living with the baby. All of these experiences have fed into Pastoral. A lot of energy, frustration, isolation and joy has gone into this record. My experience of having a child has been that from time to time I have felt emotionally transformed but in the worst possible way. Postnatal depression has been quite a big problem for me over the last two years.

“So despite this record not being about me as the mother of a young kid, this fact has definitely manifested itself in these enthused, frantic bursts of madness. There have been times in the last two years where I have been really disturbed by very present, repetitive, nightmarish thoughts brought on by motherhood. They form a kind of hyper-aware protective shell which is to do with the vulnerability created by having a kid, how you fear for them, now and in the future, on a micro and macro level. And when you couple that with the bombardment of awful things happening day after day after day, there’s bound to be a very confused energy surrounding the project.”

But how does an artist juggle the idea of looking unflinchingly at the realities of life with being the parent of a young child. I mean, essentially, how do you keep a lid on it?

She says: “I come into the studio wanting to fucking scream and smash a wall but need to get on with work. Social media suddenly becomes this barrage of stress. You have a phone which beams horror into your eyes; you cut away from that to the baby and then cut away from that to domestic life. It’s just been like that really for two years and I haven’t kept a lid on it at all. There have been moments where I’ve nearly packed it all in. There have been horrible moments. Now that I’ve finished the record I’m almost back to my normal self so whatever I was feeling was partially down to the stress of wanting to make a record.”

Is it possible for you to judge, after the process is over, if it’s detrimental to you to be making the kind of art that you do? Obviously it’s not a binary thing, there will be both positive and negative outcomes. Is there a type of equation you can bring to bear on the subject?

She looks exasperated: “Oh, Jesus, I don’t know… A lot of the mums who I’m friends with have stopped working now and they will not go back to work. I live this double life of being a smiley mum who is a member of mums groups and who goes on playdates with other smiley mums and their kids. And in that life I don’t really talk about what I do. Then I come home and when Ezra’s asleep, I start screaming into microphones and dress up in a possessed Morris dancer costume. It’s probably best I don’t talk to the other mums about what I do and god forbid they should ask me the name of the project. I think to myself, ‘Oh please don’t look my name up! I really don’t want to explain it to you! And I don’t want you to suddenly ignore me next time I have to sing, ‘I Can Sing A Rainbow’ at pre-school.’ It’s easy to feel like doing Gazelle Twin is a selfish endeavour because what I do is not the kind of work where you log onto a computer, send some emails and then log out again. It takes up every aspect of my physical, mental and emotional world. But I do feel like I have to do it. And if I don’t do it then it would be to the detriment of everyone around me. So I do consider it a necessity.”

Some fucking equation, eh.

Pastoral is a really exceptional album. Not just one of the best of the year so far but of the entire decade tQ has been operational for. It isn’t released until September so I don’t really want to get too bogged down in what it sounds like just yet, there’ll be plenty of time for that later in the year. But let us say that the hermetically sealed vision of Gazelle Twin, which first became fully apparent after the release of her second album Unflesh in 2014, has mutated but remains essentially true. With Pastoral she has created yet another world for herself with its own internal logic and rules; a world that doesn’t seem to interact with much culture that exists outside of her perimeter event horizon. I keep on forgetting to ask her but I would lay money that she doesn’t listen to that much contemporary music at all on a day to day basis – and certainly if she does, it doesn’t seem to impact on her own work in a noticeable or direct manner.

One thing I will mention here is the sheer range of voices hustling hard for the listener’s attention on Pastoral. It’s a cast of characters that includes the thunderous preacher, the rural joyrider, the net curtain twitching neighbour, the hooligan, the “eerie female folk banshee”, the teashop haunting, UKIP voting granny: “These lovely old dears having their tea and scones cooing over your child and then you hear them comment on someone walking past who isn’t white, not from round here, has a different accent and then suddenly with one comment they are rendered very evil.” She has also widened her vocal range and process to accommodate all of these figures, from her assured masculine countertenor, her rarified childlike soprano, her gruff alpha male, her matronly voice of authority; and that’s before we get to the use of vocal manipulations. Vocally alone the album stands on some hard to define ground between Michael Nyman’s ‘Memorial’, ‘Going Up’ by Coil, Henry Purcell, Anhoni, The Flying Lizards, Little Simz and Fever Ray.

(There is one voice on the album which isn’t hers though. The closing track ‘Over The Hills And Far Away’ features a field recording of a puppeteer performing the John Tams version of the 17th Century folk song on the street in Nottingham: “The lyrics really fitted with what I was doing. ‘King George commands and we obey/ over the hills and far away.’ It was just the thought of all that murder and bloodshed happening away from the rural idyll, meaning you don’t have to think about it and all you can see yourself is this green and pleasant land.”)

Generally speaking, when applied to literature, the term pastoral has three main uses. The traditional use is in reference to a romanticised Arcadian idyll, a vehicle for discussing life in the countryside, especially from the point of view of a shepherd, the second is a style of literature that contrasts rural life to that of urban life and the third is that which describes rural life in derogatory terms. It’s clear that Elizabeth Bernholz’s album is all three things: initially an idealised vision of the rural to escape into, somewhere that provides high contrast to the life left behind but in reality a trap: a microcosm of all the horror currently unfolding on the world stage.

Now more than ever we need more queer, female, non-white and working class writers, musicians and artists addressing the real nature of nature, to act as a corrective to the overwhelmingly white male establishment narrative of the countryside as healing retreat from the modern world… with all of its implied panic over immigration, Islamism, feral youth and overcrowded inner cities. We need the voices of not just Elizabeth Bernholz but the likes of Testament (author of Black Men Walking), my Quietus colleague Luke Turner, Shirley Collins who recently published All In The Downs, Suede, whose new album The Blue Hour is a Hellish rural vision of “fly tipping, roadkill and B roads” and Nan Shepherd. There are others of course, but it’s still not enough.

As Richard Smythe pointed out in New Humanist this week, trace nature writing back far enough and you find some of its roots mired in fascism. Could this be where it’s headed as well? While no one is calling Paul Kingsnorth a Nazi, Elysium Found?, his recent essay, a gaseous piece of criticism on the short film Arcadia and the dodgy blood and soil bullshit it contained, still managed to leave a sour taste in the mouth: “I defy any Briton to watch Arcadia and not feel a surge of patriotism; the real kind, the old kind. Not an attachment to monarchy or church, institution or government, idea or ideal, but the old pull of the land you walk on. The ground beneath your feet.” (In the spirit of this piece it should be pointed out that some of the strident objections raised to this ill-considered drivel did actually come from such white establishment nature writing voices as Robert Macfarlane, so kudos to him but still the overall feeling is the kind of drift back to the right in this arena as in so many others is becoming more and more acceptable.)

When I interview Bernholz, it’s literally only three days after the mirthless Tommy Robinson-inspired violence in the middle of London. According to the morning’s news, nine of the people arrested on the day have now been charged with offences, not that you would know it from the front page of today’s The Sun. What they lead with is an inspirational collage of apparently pro-Brexit imagery under the headline ‘Great Britain Or Great Betrayal’. It includes the Qatari-owned, Italian designed Shard skyscraper, a mini-cooper made by BMW in Germany, the EU-funded Angel Of The North designed by staunch pro-remain artist Antony Gormley and the most famous and long-lived of the Jurassic plesiosaurs, Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster. The front page, understandably, is roundly mocked on social media but it’s not really funny – none of this stuff is anymore.

The whole depressing affair calls to mind one of numerous stand out tracks on Pastoral called ‘Dance Of The Peddlers’, a weird and crushing experiment in trap that references William Blake’s ‘The Tyger’ while casting a baleful eye at the UK press. Bernholz says: “The voice in that song is the voice of the tabloids. It’s a voice that has become ever louder in recent years. It feels like it’s bristling at the moment and reaching its peak – hopefully just before a big decline. Where I live, the only papers you can get are the rags. I see people who seem educated, in touch with current affairs, but then I see them buying these papers and it baffles me. But it’s the norm. This is the news as far as they’re concerned. And they trust it and they believe it. I grew up in this era of tabloids. And it’s those colours again. Those colours… red, white and black. They’re the colours of fascism. And these colours are repeating themselves everywhere all over again.”

Gazelle Twin plays Supersonic Festival in Birmingham on Saturday. ‘Hobby Horse’ is out on Anti-Moon Ghost Ray today