You could argue Karen Dreijer Andersson was really onto something with her Fever Ray debut last year. With its mix of intimate arrangements, odd distancing gestures and electronic beats twisted to suit the needs of narrative form, the Knife musician’s self-titled opus crept under the skin as a kind of postmodern confessional.

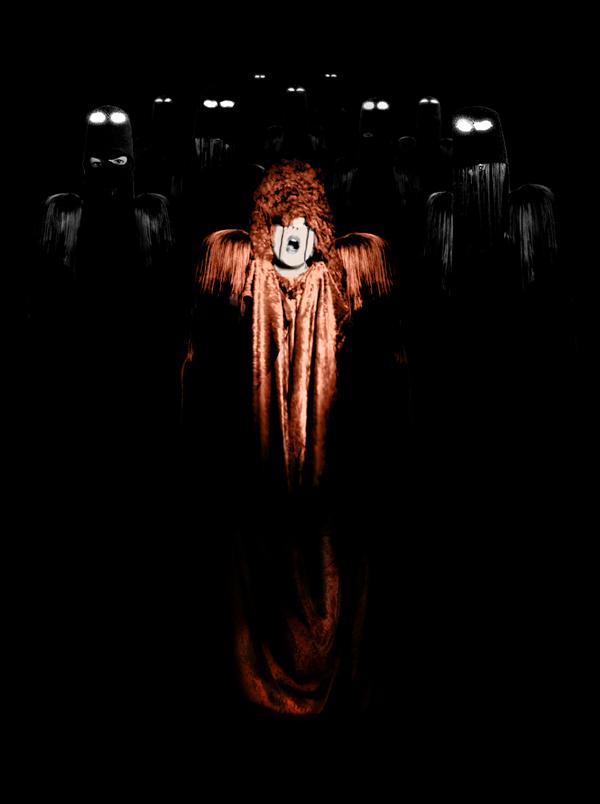

Brighton’s Elizabeth Walling attempts a similar trick with her haunting Gazelle Twin project, and her ideas appear to be taking wing. With a look inspired by the Surrealist painter Max Ernst’s feathered alter-ego Loplop, and a debut album available to hear in demo form over at Myspace, Walling is busy assembling the elements of an immersive experience to get lost in.

That record, The Entire City, is a dream-like tableau evoking Bjork, The Dirty Projectors and Vienna’s Soap & Skin as well as Andersson’s sly gift for otherness. At times it plays like a surrealist nightmare, with teeth in all the wrong places. At times it’s softer than that. It also works as a slice of urban gothic in the manner of The Bug’s London Zoo and Liars’ Sisterworld (the album is named after one of Ernst’s paintings at Tate Modern).

There are creepy, distorted vocals, menacing brass flourishes and abundant, synthetic strings and choral arrangements – apt really, since what are cities if not unnatural symphonies of sound? Great cities are also like dreams in that they’re canvases onto which we project our fears and desires. And Walling’s canvas groans with both.

Your music has been described as Art with a capital ‘A’. Do you think pop music and art enjoy an easy relationship nowadays? Who walks that particular line best for you?

Elizabeth Walling: Art and pop practically come from the same place. Both are prone to moments of loftiness just as easily as they are to spouting utter bullshit. There’s value somewhere in the middle, but it’s all down to personal taste. I’ve ‘borrowed’ a few beats from Purple Rain in some of my demo tracks, and did a cover of ‘I Wonder U’, but there’s more obscure elements such as the horn parts in ‘The Entire City’ track which were inspired by Louis Andriessen’s Mausoleum. It really doesn’t matter if people pick up on those details, like them, hate them or miss them completely, as long as the music makes an impact in one way or another. You can say the same about art, I think.

The Dirty Projectors have very sophisticated, intelligent ideas within extremely accessible songs. They’re outstanding on many levels, I’d do anything to be in that band!

How did the idea for Gazelle Twin begin to take shape? It sounds like fairly high-concept stuff in terms of your plans for the stage show. Did the gig (your first under the Gazelle Twin moniker) at Shunt in London offer a fair representation of where you’re going with this?

EW: I just became totally sick of playing by the rules with the local music scene and its many cliques. I wanted to put on shows on my own terms and not someone else’s. I’m not a confident, loud or eccentric personality, especially on stage – I go out of my body a little bit, I don’t really know what happens, but I began to feel uncomfortable when performing solo. Being ‘myself’ on stage felt incongruent with the music. It needed something more intense, but I didn’t know what. Then I played Loop Festival in 2009 and saw Fever Ray for the first time. Her show reminded me how powerful and liberating costume is, and I became interested in the power of disguise; in altering my female form and covering my face. It’s a particularly striking thing for a female singer to do in an industry where everything is image-based, and where you are normally expected to be fully revealed. I desperately wanted to talk to Karin backstage afterwards, because I had an epiphany, but I was far too scared to approach her!

After that I came up with a sort of manifesto, I started an image blog earlier this year because I had such an overflow of ideas and had to let some of it out. It’s all quite dark stuff on there.

The performance at Shunt was a try-out to see if it was all going to work. I made the costumes and installation on a budget of zero, but the effect was still intense. When I came onstage, I could hear people gasping and saying things like "What is it? Is it a guy or girl?", "It’s a Jellyfish!" and so on. They seemed to go quite childlike because they were a little bit scared or confused by my appearance – it was a great reaction. I felt extremely powerful behind my veil.

You’ve mentioned an admiration for the work of Paul Auster, Max Ernst, Fever Ray – all artists playing with notions of self, especially as it’s presented in art. Is this a theme common to your own music? What was the attraction of ‘Loplop’ in bringing together your stage attire?

EW: Identity is quite a weird concept, but then, for most of my life I have felt like I have only ever been on the periphery of one. Those grey areas of existence are what really interest me. It’s probably why I like the idea of transforming myself in the public eye. It gives me more freedom and allows me to hide at the same time. Loplop is sexual, animal and ghostly all at once – a pretty good combo for the stage. I took a lot of inspiration from that for my current costume, but I’ve also tried to make it my own by changing it. It’s not really a bird — more like a cross between an octopus, a spectre and some sort of pagan or regal costume from Elizabethan England. The other band members’ stage costumes are quite different – they’re all black and have much more of a futuristic or robot-like presence. At Shunt I basically wanted to recreate that scene from the original version of The Fog where the ghosts appear in the church as silhouettes with glowing eyes.

The costumes are not an ‘alter-ego’ nor are they going to be fixed identities for future Gazelle Twin projects. I intend to change it with each album and tour quite radically.

Why was your record named after Ernst’s painting ‘The Entire City’? It certainly gives the impression of an expansive statement of some kind…

EW: It just has a very strong impact as an image and as a title in its own right. It is a painting that I have returned to time and time again, and so, I decided to use it as foundation upon which I could develop more ideas and a setting for the album. It has an epic, slightly futurist feel which I’m keen to preserve, amongst other things. Some of the songs are more obviously ‘city oriented’ such as ‘Concrete Mother’, and ‘The Great Fear’, but there’s no prescriptive narrative. One of the songs, ‘I Am Shell I Am Bone’, is loosely about a manta ray and how "all life comes from the sea"; another, ‘Scavenger’, is sung from the perspective of a ghost. I’m writing lots of new things at the moment and I’m still developing ideas for this and the next album. It’s likely that The Entire City will be quite different to how the demo is now… I’m also considering making a free-roaming virtual world to accompany the album and change the non-live listening experience completely, but we’ll see how it goes.

Your music also shares dream-like qualities with Dada and the Surrealists – how do you go about trying to capture this particular feel? For example Ernst was well known for his use of experimental painting techniques that allowed a chance element into a work – have you tried using analogous methods at all?

EW: Apart from associating myself with Ernst’s work, I hadn’t actually made any deliberate connection with the Surrealists. It wasn’t until someone recently asked me how I write lyrics that I realised that I use free association and a slightly primordial approach in my writing method, which I guess relates to the Surrealists in some way. I rarely start out with a fixed idea or a set of lyrics. I leave everything to the moment I hit record, and I usually sing phonetic sounds against a beat, bass line or melody to get the vocal line. On a good day, it’s usually the first take that works best and I then have the task of sculpting words out of the sounds. Weirdly, it eventually makes sense lyrically. It’s a very strange process because these ideas appear to come from nowhere, I guess a bit like using the frottage technique with music. The painting technique that is, not the rude one.

Lastly, can you tell me more about how your appreciation for the work of (barking-mad Renaissance composer) Carlo Gesualdo?

EW: He’s just another of my obsessions along with Prince. I only discovered his monstrous catalogue of guilt-ridden, sex-crazed music about five years ago. I was doing a commission for Brighton Early Music Festival and the ensemble who performed my piece played me some Gesualdo one evening. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. His harmonies are very strange, and often quite jarring. They’re completely out of place for the harmonic rules of the period. When I learned more about him and his personal life, it just got better and better. I’ve tried to use some similar harmonic ideas in my work, but it’s a pretty obscure reference.