True to the bone, musical oddball Gary Wilson has experienced a career path stranger than even he could have ever imagined. Having started off in the 1960s as a multi-instrumentalist and home recording prodigy – who found himself discussing his work with John Cage when he was only 14 – Wilson winded up recording a couple of fascinating albums before fading into obscurity from the early 80s onwards. That is, until his name popped up in a popular Beck song – ‘Where It’s At’ – at some point in 1997. "Passing the dutchie from coast to coast like my man Gary Wilson who rocks the most," sang Beck. "Who?" asked fans.

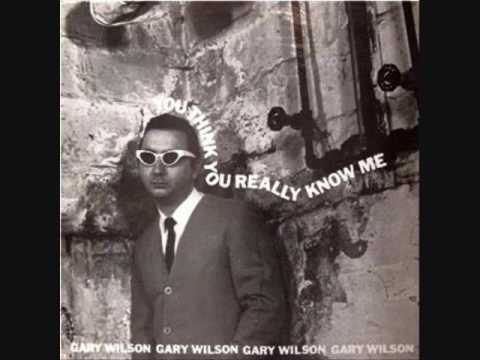

His legacy up until that point was virtually non-existent. Having self-recorded and self-released one now-highly acclaimed but then widely misunderstood record in 1977, the infamous, You Think You Really Know Me, he was unable to ever be remunerated for his self-perceived talents in any meaningful way. Admittedly, the music is really weird, even for people who like weird music: highly sexualized avant-garde electronic lounge jams. But his talents – from songwriting to self-recording – were so many and so unique, that it’s difficult to understand in 2014 how or why he never caught on.

Wilson subsequently dropped off the map entirely, to the point that his growing new fan base was unsure whether or not he was even still alive. Luckily, interested label Motel Records eventually found him in 2002, working in a San Diego porn shop and side manning the odd nondescript lounge act.

Since then, he has re-released a lot of his old work to much critical acclaim, and now in his sixties, gone on to write what is some of his best work to date. The singles dropping from his soon to be released Alone With Gary Wilson LP are magnificent little weird creations.

We got in touch with the prodigal recluse to discuss his legacy even further. When he answered the phone in San Diego at around sunset, he had forgotten about our appointment, said he had just finished having sirloin burgers with his dog, but still happily took the call.

Why do you think it took people 25 years to catch onto your music and understand it in a more widely accepted sense?

Gary Wilson: Well, that’s something I could never really figure out myself. When I pressed and released You Think You Really Know Me by myself in 1977, I was trying to shop it around in NYC for a while, and promote it through places I thought would dig it, like CBGB, and record labels would often tell me that they really liked it, they’d have my poster up in their offices, but they told me had no idea how they would market it. And that always perplexed me, because I thought, ‘Well, if you like it, it’s already marketing itself, what difference does it make how you market it?’ And I could never figure it out. I even then took it to the West Coast, to Frank Zappa’s label [Bizarre Records], and thought I could at least get him interested, but just could never get a bite. Funnily, in the end, I became desperate for money, so I ended up going to a used record store and unloading like 50 copies of it at $0.99 a piece, less than it cost to make them. Why that was the case, I still don’t have an answer for. I just succumbed to the situation eventually.

Do you think there was an element of self sabotage at all that played into that? I mean, you famously used to throw flour and paint on your audiences and would purposefully book yourself into the wrong venues too – like polka and waltz venues for old people – just for personal kick.

GW: Sometimes you had to entertain yourself too, but I always saw that as part of the larger element of Gary Wilson music that I thought people would understand. I mean, it was also the time of experimental college music and weird punk, don’t forget, like the Talking Heads, so you’d think audiences would be understanding. But I’d bring a Fender Rhodes piano to the stage, and people would get angry. So I’d say ‘Hi. This is Gary Wilson music’ and do my thing, and then audiences would just get furious. You know, two or three songs in, they would leave or often actually want to hurt me. [Laughs]

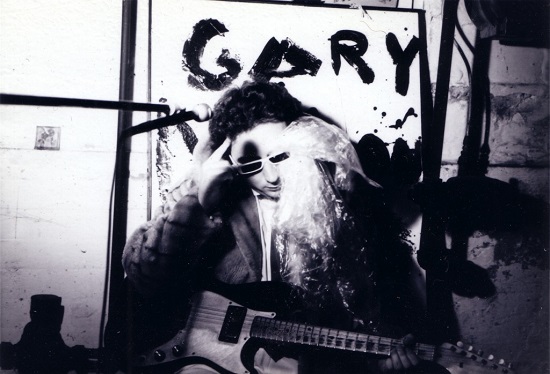

Gary onstage at CBGBs

Do you think then the Internet and the slow desensitizing of people – for example, people don’t go to therapy anymore because of scary movies like they used to – had a hand in opening up the doors for you and allowing the music to market itself more?

GW: Well yeah, for sure you know. That was the whole big thing I guess. And it’s funny, when I was resurrected, which is what I call it, it seems people wanted me to be even wilder and more outrageous than the early days, which was weird, because I was used to getting the plug pulled. But then [after all those years of silence and nothing] I was dealt with audiences who would get unhappy if I didn’t take flour out and throw it on them. It’s great in a sense. I love that sort of thing, so it’s much appreciated. But, I think it was all just a matter of timing.

Growing up, is it true that you were somewhat of a childhood musical prodigy? A multi-instrumentalist playing guitar, bass, organ, cello, drums by grade school, and recording it all to tape by middle school?

GW: My father was a musician, and he made sure all his kids played instruments. And I really took it on and got into it. He played in a jazz band so he had this big organ at home I’d play around on, and then I used that to teach myself guitar before ever having one, by transcribing the notes onto fret diagrams I would draw. And I just kept growing in ways like that. In school we had to play a string instrument so I went for the cello and string bass and was formally trained in that department.

And then I learned about recording, and got my hands on a tape recorder, and a friends Dad worked for McIntosh [high end audio manufacturer], so he had stereo equipment laying around, and I’d go over there and play with it all. I really got into that, trying to mimic my favourite records and all that, loitering outside of studios and stores to get throwaway equipment or learn anything I could. And I just kept recording and recording. And even in those days I would go down to NYC and try shopping those recordings around. I wish I had some of those really early tapes still, they would sound amazing to me.

Was it not strange, being that young recording yourself, shopping around etc? It’s more commonplace now but in those days hardly anybody had the chance to record at all let alone record at home.

GW: Well you have what’s available. If you know what you’re looking for, it’s always possible to find it. It was always organic so it never seemed strange to me I guess, people thought it was though.

At an early age, you saw the Beatles live at their legendary 1965 Shea Stadium concert, didn’t you? What was that like?

GW: Very exciting. I guess by that point I was a Beatlemaniac, that’s what you’d call it, you know, my room was covered in their posters and all that. Originally I was into Dion and Fabian and 50s doo-wop and stuff like that, from about the age of 7 or 8, and then the Beatles came about when I was maybe 11 or 12, and changed everything. And so the concert, boy, it was just amazing, just so exciting. What I really remember and noticed though, was just how deafening it was. You know, with all the girls screaming, and we’re talking fifty/sixty thousand, simultaneously, at the top of their lungs.

But that whole time was exciting. Garage bands started popping up all over the place. Real garage bands. People in actual garages. And it lit things up.

Musical ability aside though, your upbringing and musical tastes seem to be quite normal and run of the mill. Where did all the wackiness come from then? Did you get into LSD at some point?

GW: No actually, not at all. I never really went for that. But soon after the Beatles concert, I started getting really into experimental music and people like John Cage, and he was hugely influential on my approach to music and recording and what not.

Picture courtesy of Western Vinyl

Right. You actually sent him your music at some point and he asked you to come hangout and talk about it, is that right?

GW: Yeah, when I was about 14.

That’s sort of a success in itself isn’t it?

GW: I look back at it now and think, ‘How the hell did that happen?’ I was young and writing weird experimental music, and one of my teachers suggested I send some of the scores that I was writing to him. I thought that was a bit weird, but John Cage was listed in the phone book in those days, so I just called up his number and introduced myself and what I do. I was into the most extreme avant-garde and experimental music at the time, and was trying to write that sort of stuff. And so he seemed interested, so I sent him some, and then he actually responded by inviting me to his house. It was crazy.

He was such a humble guy. My Mom got lost driving me over there and so we stopped at a general store to call him up, and he came down to get me in his car. And the whole time I’m just thinking, ‘Grad students from Julliard would kill to have a one on one with John Cage’, and for some odd reason, here he was, coming to pick up this random little kid from Endicott.

Maybe he thought it was very good.

GW: I don’t know what it was, I didn’t ask. It just happened. And so then, I’m sitting with him and he’s going over it and rubbing his chin, saying things like ‘How’s a trombone player going to interpret that?’ or ‘Maybe that should be a crescendo rather than a slide,’ and he’d scribble on the pages and make adjustments. And I’m pretending to work with him while just being completely bewildered that I was there.

And then, after that was done, he started to talk about music in general, and performance, and he told me, ‘If it doesn’t irritate your audience, you’re not doing you’re job properly.’ He explained to me how he was never able to sustain himself with music until he was 50 or so. You know.. [laughs].. making small talk with John Cage. And all of this ended up being incorporated into what became Gary Wilson music. I look back at it and it’s just marvellous, all these combinations of events and experiences.

So my attraction to strange music and experiences was a lot more organic and natural and grounded than people would expect, rather than just drugs.

But you were aware that walking a duck on a leash around your neighbourhood [something Wilson infamously used to do] would be considered inorganic right?

GW: Well yeah I had pet ducks and you know, they’d need walking. You know, you’re younger; you’re trying to find yourself. Different times. There were times when I was a loner too, and experienced all that world had to offer too. Just different stuff, I guess.

Interesting, because one of the most alarming tracks on You Think You Really Know Me is a track called ‘Loneliness’, where there’s a movie playing followed by running water and you’re moaning things like "sometimes I wish I was dead" and "someone help me please." It’s a far cry from the Beatles and Dion.

GW: Well, yeah. I was a loner in the sense where I was a curious little boy in a small town, looking for girls and experiences, and it was a hard deal. But yeah, that’s an interesting song. I was also really into classic horror and scary films [like The Mask and Carnival Of Souls]. I loved the sounds those things had in them too. That dark, weird and dreamy feeling. And I incorporated a lot of those ideas into the music, too.

The album’s also incredibly sexual, often borderline pornographic [see ‘6.4 = Makeout’]. Is that something you were really into too?

GW: Well, not as a kid, no. That was just me expressing myself in my own way. You know, trying to figure out what it all meant. Being extreme, but honest and fun, all at the same time.

But you were eventually found by Motel Records working in a porn shop in San Diego, right. That’s just a coincidence?

GW: Kinda. I wouldn’t say I was ever really into pornography. I was just hanging around people that had a really relaxed attitude towards things, and worked in lounge bands with naked girls walking around. And one thing leads to another and… yeah. [Laughs] That was just whatever, you know? You need a job etc.

One of the most remarkable things about You Think You Really Know Me is the quality of it, way more hi-fi than what we’ve now come to expect from home-recorded music, especially from the seventies. Was that all also self-recorded?

GW: Yeah, after a few stints at a studio, it ended up being mostly home recorded. I was always attracted to a certain level of fidelity and wanted that on my records too. I always considered myself a bit of an amateur audiophile as a kid, so that was really important to me. I was very interested in sonics, and how people got the sounds they did, whilst minimizing background noise. I needed it to be a certain quality. And I found ways to make it work. I mean, You Think You Really Know Me me was recorded in the worst conditions imaginable. I was in my parents’ concrete and dank cellar, with the pipes clanking and the ceiling dripping when it would rain and all, which you can actually see on the cover of the album. No acoustics at all [laughs]. So I would just figure out ways. By that point I’d been home recording for over a decade. So I’d put the microphones really close and stuff, record it at certain volumes and angles, throw t-shirts over drums to get a certain kind of sound, and all that sort of experimental stuff.

But even the performances on that record are strangely on point. The majority of home recordings are usually covered in take mistakes, or parts where layers don’t match up, because it was so hard to edit on tape back then. But none of that marks your work.

GW: Well, it was very important for me for it to sound like it was a real band, so I couldn’t have any of that. I didn’t want it to seem like a weird home recording project I needed it to sound like a professional band, and I focused very specifically on that until I felt like got there. Anything that didn’t sound like it was a genuine four or five piece band had to go. I put a lot of guts and hours into that stuff. It was important to me.

So what is ‘6.4 = Makeout’?

GW: [Mumbles] It’s.. yeah.. I don’t know.. it’s.. it’s like.. it’s a secret.

So it’s not some type of rubric: that a girl must register as at least a 6.4/10 to be of Gary Wilson standard, or something?

GW: Maybe I’ll say one day but, leave it for now.

Jumping to 2002, your self-proclaimed resurrection, it seems you started releasing new material straight away. Was the majority of that written post-resurrection or had you been writing and recording in your years of obscurity?

GW: A bit of a mixture I would say. With ‘Mary Had Brown Hair’ – which was the first release of new material after they reissued Forgotten Lovers [an album of singles, b-sides, rare recordings and unreleased tracks from the 1970s] – half of those things were ideas that I’d been playing around with for a while, and half I guess were new ideas I’d come up with. Just a mix and match. But by the time I got to ‘Lisa Wants To Talk To You’, that was mostly new stuff.

Motel Records was more interested in my older stuff though. And that’s one of the things, labels are often trying to dig back and release old stuff but I just keep trying to sidestep and move ahead, because I’m not into that sort of thing really. There is another upcoming release of old stuff though, weird ideas and offshoots. Like one time a friend and myself smashed up a piano, smashed it to bits. We just took a brick to it, and recorded the whole thing in a very artistic way, with great, great fidelity. And it just produced spectacular sounds. I don’t know how we did it really. But that stuff will be coming out shortly, too.

It’s great that, after all these years, it seems you haven’t lost your touch at all. One of my favorite songs is actually your newest, ‘I Just Want To Hold You In My Arms Tonight’, which is also supposedly coming out on an album soon.

GW: Yeah, that’s a new one. That was supposed to come out on an LP this summer called Alone With Gary Wilson. Actually I was just thinking right before you called that I needed to call these guys up and see what the hold up is, because I actually have even another album in the can too that I want released after that one.

I just try to keep going with it. Like always, when the mood hits, I just lock myself in my room again and start tinkering and recording stuff on my own, in the same way as always, to tape, still not a fan of the computers.

You sound like you’re enjoying yourself now, with all the heightened interest.

GW: Well, yeah, I thank God for it. It’s a big change. I just, I don’t know what to say. I’m just completely humbled by it all. It’s an understatement to say that I just never expected that to happen, especially when it did. In fact I think the day they called me up I remember taping my tearing shoes together to get to my minimum wage porn job and just embarrassed about the whole thing. And then it just exploded, so, unspeakably surprised and thankful and yeah, all of it.