More than any of his other releases, Richard D. James’ Surfing On Sine Waves album, recorded under his Polygon Window alias and released in 1993, evoked the wild Cornish landscape so beloved of its creator. Surfing… was James’ love letter to Cornwall. It was as moody and magnificently brooding as the granite cliffs of the Lizard Peninsula with its ancient fern-packed hedgerows, and brought to mind stark vistas coloured purple, brown and grey, the crumbling towers of abandoned tin mines; and the alien weirdness of the Goonhilly Earth Station.

Electronic music often reverberates with echoes of the place of its creation – think Detroit, Berlin, even the endless skies of the Norfolk of the Border Community artists – and has special meaning to those who also know the landscape intimately. I wouldn’t feel such an affinity with Surfing On Sine Waves were it not for my family ties to the Lizard and regular trips to the area throughout my youth. So anyone with even a passing association with The Wirral Peninsula, the chisel-shaped cul-de-sac between Liverpool and Chester, should feel an instant connection to Engravings, the spellbinding debut album from Matthew Barnes, aka Forest Swords. Engravings is steeped in the wild spirituality, harsh beauty and Viking heritage (The Wirral was a Viking settlement in the 10th century and Old Norse, the language spoken in Iceland today, was once spoken there) of The Wirral, where Barnes grew up and still lives.

Referred to as "the wilderness of wirral" in the 14th-century poem ‘Sir Gawain & The Green Knight’, Barnes didn’t just use the region for inspiration, he physically took his music to the landscape, mixing the album under darkened skies on Thurstaston Hill during our seemingly endless winter, working for as long as the weather and his laptop battery would allow, before retreating and then returning until the process was complete. Specific places are directly name checked, such as ‘Thor’s Stone’, the red sandstone outcrop on Thurstaston Common, and ‘Irby Tremor’, named after the village of Irby, a moniker of Viking origin meaning "the settlement of the Irish".

With so many electronic artists precious and intent on shrouding themselves in a cloak of mystery, it’s refreshing to find Barnes so candid. You might not have seen many photos of him, but during our interview he is happy to lay his creative processes bare and talk at length about his work – only not to an audience: he gets off the train he is on when I call. "I hate being that guy who’s spilling his business all over the train," he says in a strong Wirral accent, often referred to as "posh Scouse".

Engravings is a brilliant album. It feels to me like a far more confident record than Dagger Paths. You have really honed your sound. It’s sonically uncluttered – there is lots of space for the various elements to breathe. Was this an intuitive thing for you, or is it something you have had to learn?

Matthew Barnes: I think partly that’s something that just comes with experience. You spend so long making music and trying things out, and suddenly when you’re more reductive about things it automatically sounds more confident, because you express your ideas with a lot more conviction. The space thing happened quite late in the process. I ended up stripping away lots of layers and exposing the skeleton of it, almost. It’s very easy when you’re working on a computer to add on hundreds of things that are completely unnecessary elements. I was listening back to Dagger Paths and it was a nice snapshot of where I was at that time and the way that I approached making music, but for Engravings I didn’t want to bury all the sounds and textures underneath a load of atmosphere. And when you take away sounds you make your own atmosphere.

Your music evokes very strong emotions in the listener – it’s very powerful and melancholic. Does the process of making music leave you feeling emotionally drained?

MB: Yeah, I do actually. It’s like having a deep conversation with someone; a really deep dialogue. You know with your best friend, when you’re talking about really personal things? You almost don’t want to talk about it after a while because you get so exhausted and drained and all your energy goes. It was quite an interesting process making this one, because I was honing in so much on the sounds and different kinds of melodies – it triggered something within me. The longer you spend doing that, the more exhausted you become. It’s just tiring after a while.

In terms of the process of making music, you don’t come across as an equipment junkie – someone whose sound is governed by the latest synth or piece of software. Is that right?

MB: Yeah. My set up is really simple. I enjoy that because it means that I don’t have loads of toys to play with and I’m not endlessly trying out different synths. My palette is fairly small. When I was a teenager I got given a four-track tape recorder for Christmas and I did my first experiments with music on that. I really liked the parameters of just using four tracks for something. You can get lots on four tracks, but at the very base level it is just four layers, and I became used to that. I’ve never been one for spending lots of money on equipment for fear that they’ll gather dust. I just like the idea of working with fairly cheap software. I work on a really shit hundred quid guitar. I don’t have a really big studio set up. A lot of my favourite producers are the ones who worked within certain limitations and created really amazing things. There’s loads of really great music made at the moment on really cheap entry-level software. It’s about the sounds that you create. It’s a complete cliché that it’s not about the equipment that you use, it’s what you do with it… but it’s true. That’s always been true and it always will be.

There’s a very organic feel to Engravings. It’s cutting-edge and modern, but also very ancient and traditional. It goes right back to our folk roots. It’s very clever balancing act.

MB: Yeah, I would agree with that. Part of that is a conscious decision and part of it is just that I let go with it. I’ve never really got into a song and thought, this is what I want it to sound like, or this is what I’m trying to achieve here. I just let it go. So it almost has that element of… it’s quite meditative in a way, shamanistic. You let something… You let some kind of spirit…

Take over?

MB: That sounds a bit weird, but I genuinely think that a lot of things come from places we can’t really explain. I wouldn’t like to say some spirit created this record – that sounds completely ridiculous. But you do get into this Zen zone where you’re not really conscious about what you’re making. Also, I guess I’m really attracted to sounds where you can’t really place when they were created. I don’t think you can listen to my stuff and say what kind of software of synths I’m using or whatever. It exists in its own sphere or space, and isn’t really anchored down to any time period. I’m really attracted to things like that. Part of that is because I hate nostalgia. I find that very ugly. I never really like looking back at things in a rose-tinted way. So by creating stuff that doesn’t have any time period associated to it necessarily, I free myself from that I think. Well, I hope to. Even if it’s just personally. It becomes a stronger piece of work because of it. It’s like a big rock that’s unmoveable. You don’t really hold any nostalgia towards it. I found that whole chillwave thing unsettling. It was so rooted in nostalgia, it was a bit depressing. So I always try and make music that you can’t really place. It sounds modern because I listen to modern music, but I prefer it to be a little bit looser.

It’s a very unique sound – you combine guitar, drums and vocals in a way that nobody else does. You can tell it’s a Forest Swords record immediately – there’s a mood you create that is completely original, though there are some obvious genre reference points, like dub and hip-hop. But were there any specific influences around when you were making the record, musical or otherwise?

MB: I didn’t listen to a lot of music when I was making it and I generally don’t listen to a lot of music. I don’t really consume it in the way that I should do, as a twenty-something nowadays. I’m very selective. I’m very aware that if I do decide to buy an album, I’ll give it the time and space it deserves. I’m not really one of those people who are constantly downloading stuff off blogs and Soundcloud.

How about when you were growing up? Was there an album then that had a profound effect and was very influential to you at the time; perhaps that still resonates in what you do?

MB: There were a couple of Riot Grrrl records. Like every teenager, I got into metal. I was really into Deftones, I think they’re an amazing band. From there I discovered things like Fugazi. But the main one for me, and I’ve become a lot more aware of it since I’ve started talking about my own music, is Taking The Rough With The Smooch by Huggy Bear, which was a pretty seminal record. It was incredibly angry and powerful. What I took from that was that you can do what the hell you like, and people will still engage with it on some level. So long as you are completely honest about what you’re doing and there’s a lot of truth, it will speak to somebody on a profound level. It taught me that. It also taught me that you can do what the fuck you want in life. You don’t have to subscribe to any preconceived genre or anything like that. It’s a very powerful thing to discover those sorts of bands at such an impressionable age.

In the same that way that bands like Huggy Bear were completely DIY and in control of all facets of what they did, you are too. You do all your own artwork and you don’t have a manager, as far as I’m aware.

MB: It’s very important for me to keep everything in house. Part of it is that I’m a bit of a control freak and part of it is that I studied as a designer and went to art school, so I’m used to directing my own projects. It’s an extension of that. I have a very singular vision about what I want. But it is good to collaborate.

I think the notion of a being a control freak can be quite a negative one. But if you trust something to someone else, they might not share your vision. It’s a big risk to take, especially when you know exactly what you want and have the skills to execute it. They’ll never be as connected to it as you are.

MB: Yeah, that’s the thing. The music that I make is so deeply personal so it’s quite hard to articulate the things behind it to people. Especially if, say, I tried to get someone to create my artwork for me. It’s hard to reduce it down to bullet points. It’s a very difficult process. I can’t see myself ever not doing it. It’s so intrinsically part of the music for me.

You mixed the album outdoors, on Thurstaston Hill in The Wirral. What’s the significance of that location to you? What was the actual process like, and how do you think it has affected the final sound of the album?

MB: It’s quite an iconic place on The Wirral. It’s got some heavy significance in terms of its history, and when you grow up here you’re always aware of it. You always pass through it. It’s always there in some form. Also it’s a really beautiful place. So much of the record was created indoors on a laptop in a darkened room, and I felt like it just needed that light to it – I needed to change focus and shift my perspective a little bit. Taking it outdoors did that automatically. It’s almost like a secondary experience to the atmosphere.

How did you actually do it?

MB: Just with my laptop on my knee, that’s all it was. It was really easy. I found it a lot easier to do it outside than it would have been if I’d stayed indoors. So much of the record was done in a very focused way, and pored over, it went through lots of revisions. By taking it outdoors and doing it in a very fast way, that felt kind of punk to me. It connected me back to those bands I was talking about. You just do it – finish it, work it, get it done. I did it song by song. I had about three hours on my laptop battery, so I’d do it and then go home and recharge it, and then go out again…

And pray that it didn’t rain.

MB: The weather wasn’t particularly nice. The winter seemed to last for about four months longer than it should have done, so I only actually finished it in May. It’s been quite a fast turnaround. It was a very interesting experience. I initially wanted to record the whole thing outdoors, but logistically it wasn’t possible. So it was nice to have that balance. It felt like a nice way to finish it off.

Is it something you’d do again?

MB: Yeah, totally. I don’t know why more people don’t do it. I’ve never really heard of any bands who’ve done it before.

Lots of musicians go outside and collect sounds and then bring them back into the studio that way…

MB: But that’s still very much focused on an indoor studio. Especially with electronic music, you don’t really need microphones or anything – it’s all an internal process.

The Wirral is obviously important to you. What was it like growing up there, and what influence has the area had on your music, direct or otherwise?

MB: I suppose one of the biggest things is that it’s quite separate from the nearest city, but it’s still very accessible, so I could always dip in and out of it when I wanted. Liverpool’s only twenty minutes away from where I live, so it was nice having that – being part of something and feeling connected to a city, but also feeling like you have your own space and you’re existing in your own world. I had a really nice time growing up here. It’s a nice place. There’s not a really big arts scene or anything, it’s pretty suburban. And that forced me to use my imagination a bit. Also, being an only child helps to push your imagination in different ways and opens different doors that you wouldn’t have had normally. It’s nice to feel that I’ve made a record that is rooted in the area. There’s not much culture or art around here that is. It’s nice to give something back. There’s loads of albums rooted in London or Liverpool – the big cities, but there’s been nothing around here like that. There’s nobody of significance artistically that I could pull from.

You’re not affiliated with any scene or any other artists, and you work in isolation. Would you like to feel more connected to something outside of yourself and where you are living? Do you ever wish there was more of a scene in The Wirral that you could be part of?

MB: I’m quite happy in my own space. I think it goes back to being an only child – it’s not loneliness or a lonely feeling. You exist in your own world. You can dip in and out of things, but I don’t feel the need to be anchored to anything or anyone else. The unfortunate thing with Liverpool is that you need a lot of friends to be able to do anything there. It’s one of those places where it’s about who you know. And because it’s such a small city, there are various spheres of things goings on, and there’s occasionally some crossover but… It’s frustrating in that way, and it feels like I don’t really have… I mean, I love what’s going on there, and it was really important for my musical growth as I saw lots of bands there – loads of cool punk bands and electronic bands. But in terms of the music scene, there are great things going on there. I know people in bands. I went to art school with one of Stealing Sheep. My best friends all work in insurance and things like that. I don’t want to hang out with musicians. I can’t think of anything more dull than talking about music all the time. My head’s constantly spinning, I need to switch off.

You’ve been involved in other more esoteric projects, such as audio responses to architecture and experimental sound installations. Do you find these more liberating than the rather more controlled confines of an album project?

MB: Yeah, absolutely. You can work to your own brief and create what you want on your own terms. You can sort of do that with a record, but there are still strict parameters. It’s got to fit on vinyl, it’s got to be listenable and take some kind of traditional form. It’s still very much a boxed in thing, but when you work with installations or do sound art, you work to your own brief. It’s very liberating to work outside of those conventions. It’s a lot more exciting too, because you can introduce different threads of ideas and it’s a different audience as well. It’s not just about putting a record out and then you get getting reviewed. It’s outside of that process. It exits in its own space. I’d definitely like to pursue it a bit more. I’ve been really into looking at performance artists and how maybe in the future I can incorporate things like that with sound.

Are you planning on touring the record?

MB: There will be some more traditional live shows with a visual side. I’m working on that at the moment with a really talented guy from Liverpool. There’s going to be projections and things like that.

What’s the live set up?

MB: It’s me on electronics and then there’s a bass player who is a really good friend of mine. He’s my connection to the Liverpool music scene. He’s in a lot of different bands and he knows everybody. I hear everything second hand from him. It’s great to play with a bass player. In future I really want to branch out into installation work and sound art work in different forms. I love the live set and how people engage with it, and it’s great to see different countries and cities, but it doesn’t really require you to be super creative night after night. Installation work or working in a fine art sense gets me ticking a bit more.

I think the problem is that the physical format encloses and creates barriers because people are making music purely for release. But there’s so much scope for music to be used in lots of different ways, like it is with classical music. It doesn’t have to be about making an album.

MB: Yeah, that’s a really good point. It’s the same with folk music in a way. The music takes on its own physicality over time and changes when more people get to grips with it. With the traditional music release there’s not that aspect to it. I’m definitely looking at ways to open that up a bit more. I like the idea of releasing records and I love having those bodies of work as permanent fixtures in my life, but music needs to be a bit more open-ended. There needs to be more of a dialogue going on. A lot of it is hypothetical in my head, but a lot of the ideas that I have don’t really fit into traditional structures. They’re more suited to a fine art sense. So I’m just waiting for those opportunities to come up where I can do that.

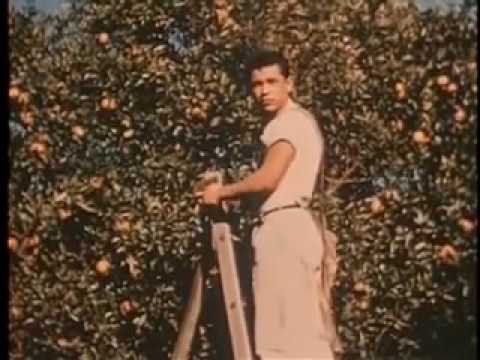

Your music lends itself brilliantly to film – the video for ‘Miarches’ [from Dagger Paths] is amazing. The music works so perfectly with the footage. Where did you find it?

MB: It was on a DVD that my friend gave me, of old American public information films from the 1950s. That’s generally how I work. I have to find things that… It’s like when you put a key in a door and it doesn’t quite go – and then all of a sudden you find the sweet spot and it goes. It’s like that for me with visuals and sound. They all have to fit together in my head and it all has to sound right. It’s a very subjective thing, I can’t articulate it very well, it’s just something that sounds or feels or looks right to me. It fits together in a perfect way. I did all the videos for Dagger Paths myself. When I saw those public information films they just seemed to fit so well. The colours of them and the narrative and the emotions on people’s faces and the textures on film – they all seemed to work together so, so well. It was like an epiphany and I just had to do it. I was very conscious to recut it so it fitted with the music. It wasn’t just a film that I plonked my music over. I cemented them together. I hate that with samples as well – I can never wholesale use someone’s sample. I’m very nervous about doing that, because it doesn’t feel like my own. I can’t just take someone else’s work. Whereas if you re-contextualise it and rework it, reshape it and reform it – it feels a lot more like your own work, and that you contributed something to it.

You had some problems with tinnitus, to the extent where you almost considered giving up music. How did it feel when you were going through it? What would you have done if you couldn’t have made music anymore?

MB: Just carried on with life really! I think people put so much weight on being a musician. From a music fan’s point of view as well it’s like… you know, like when you hear that a musician’s got a day job, and it’s quite shocking. But when you’re actually living it, it’s a completely normal thing. So if I wasn’t doing music I would just create other things. It’s not a big deal to me. I’d move on to something else. There’s things I want to do with film, with installations, I can still design magazines and do design work. I have a compulsion to create. If music isn’t there it’s just one less thing I have to do. [laughs] Not that I would ever wish to not be able to do music. But I work in a very wide sphere and music is only one facet of that. The good thing about Forest Swords is that it opens up doors in other areas that I wouldn’t have necessarily had access to. I’m talking to some directors about working on films, and not even necessarily musically – also creatively having some kind of input into it. This project feels so fully formed to me when I put it out into the world, and people respond to that. They can see that I can do all these elements myself, and they know that I can do that. I love music and it’s a very liberating thing to do, but I have so many things in my life that I can put my creativity into.

Your chosen recording moniker and certain track names and sleeve imagery suggest an interest in ancient Viking and Norse legends. Where does that interest stem from?

MB: There were lots of Viking settlements in the Wirral. There’s a museum that’s just opened down the road containing things they’ve found locally – lots of stones and there’s a child’s coffin. They found a longboat nearby a couple of years ago. So it’s very much ingrained in what’s going on round here. It’s quite an intangible thing, but a lot of the vibrations are very Nordic. Place names stem from the settlers. The name Forest Swords just felt right for the music I was making. I was two or three tracks into Dagger Paths, and I looked at the sounds and the textures, and it sounded quite ancient in that way. It definitely felt like it was connected to something ancestral, from our past, but not something nostalgic. This local area is very much connected to that time in history. I have more of an interest in it now I’m older. They don’t really teach local history at school. And as I’ve started to create more, I want to give a nod to these things. So many people leave this area because there’s nothing going on. I think that’s a bit unfair. You have to give it its props, give it its dues for what it’s got.

Do you think you’ll stay in The Wirral?

MB: I’ll always have some kind of base here, but I’m very much interested in exploring other places. I already have places in mind to make the next record. I think whatever I do will always have some kind of connection to the environment.

But a different environment would provide a different inspiration and a different record.

MB: Yeah, exactly. It would conjure up a different sound palette, a different way of working, different techniques… I’ve been going to Chicago quite a lot because I’ve got some friends over there, so I’m thinking maybe of doing the next record over there.

Are you going to make a jackin’ house record?

MB: [Laughs] Yeah! I had a bit of a religious experience there a couple of years ago. They have free concerts in the park at lunchtime and various folk things. But one day they had Chicago house DJs. It was lunchtime and all these kids were off school and they knew all the words to every single song and they were dancing with adults. There this incredible family atmosphere – this joyful, joyful atmosphere. And it was the first time I’d ever made a really conscious connection between the people, and the energy of the people and the personality of a city – the architecture and the location of it and the layout of the place, it all came together in one thing. It was kind of emotional in one way. You could very clearly see those connections being made in front of you. It was amazing to watch, and ever since then I’ve felt like I’ve got a deep connection to Chicago. It reminds me of Liverpool in a lot of ways. The history of it is very similar – the more modern history, the personality of the people. It’s interesting to go to other places and draw parallels with what you know. Likewise Iceland – I went to Reykjavik recently. It was incredible to feel those ancient, beautiful vibrations very clearly. It triggers all these ideas in my head.

The record you’ve made has got such a strong sense of place, I think it’s a really interesting idea for you to go to other places and absorb not just the musical influences, but the architecture and people and culture and bring all those elements into your sound. Rather than you just standing still and making another record that sounds like Engravings. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but using another place as an inspiration – as a jumping off point – is a really intriguing concept.

MB: I think I might do that – every record is based somewhere else. It’s all about perception really, how you perceive the energy of the place. I studied mediation for a bit last year so I feel like I’ve become more attuned to energy and vibration and understanding the present a bit more and the immediate environment. It would be an interesting thing to explore. Chicago isn’t one of the most obvious places. A lot of people go to Berlin or London. But Chicago’s an underrated city – like Liverpool really. It’s looked down upon in a way. People from the main cities in America don’t think that there’s anything of note going on there. But I get something on a deeper level from it. I feel like Engravings is… not necessarily my goodbye to where I live, but it’s the record that I want to make here. I’ll never completely up sticks and ditch it for good.

But perhaps you’ve wrung out all the inspiration from it.

MB: I think that’s a good way of putting it. I’ve done all I can with what I have here.

Forest Swords’ Engravings is out now via Tri Angle

Forest Swords plays at Corsica Studios for Unsound London/BleeD on September 28th, alongside Durian Brothers and Robert Piotrowicz – click here for more information and tickets. He also plays at this year’s edition of Unsound Krakow, which takes place from 13th-20th October – visit the Unsound website here