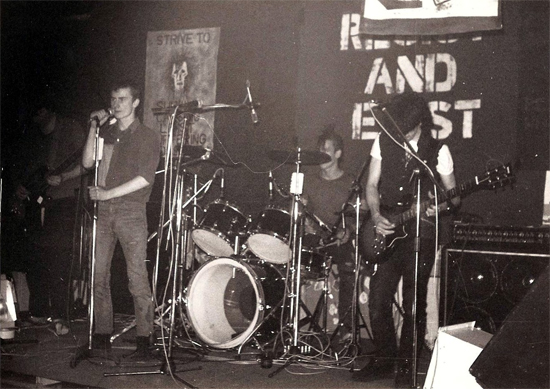

Things come and go, old things reappear and become new again, and nothing that ever existed truly dies. There isn’t a week that passes without a slew of reissues and reformation tour dates, and while the quantity of these resurrected artifacts naturally leads to an overall dearth of necessity for re-polished, re-presented music, we’re now privy to most of the music that has ever been recorded. For every thousand ‘previously unheard’ selections of out-takes discovered in dead producers’ basements or Rolling Stones mono versions previously thought unnecessary, there returns a record as vital as Flux of Pink Indians’ Strive To Survive Causing Least Suffering Possible.

Originally released in 1983 on the band’s own Spiderleg label, Strive is by no means a snapshot of a time. Its anti-capitalist, vegan, anarchist ideologies still resound today (possibly even more than they have in years), and the music is as uncompromisingly fierce as it was 30 years ago; the re-release is more like sharpening a knife than remastering a record. While Flux’s subsequent moves into dub and electronic music were significantly more palatable than those of their peers, Strive remains as vicious, as informed and as fucking inspirational as a punk rock record should.

With bassist Derek Birkett busy running his One Little Indian label, the Quietus spoke to vocalist Colin Latter and guitarist Kevin Hunter.

We’re living in a culture of reissues and reformations. This is the second time you’ve reissued this album, and you played it live about five years ago. Do you think releases have decreasing shelf-life these days? Is it more disposable, and should people be reminded of things past? Is it an artist’s duty to do that?

Colin Latter: This has been a great opportunity to put together the original album, the demos and the recording of the Shepherd’s Bush gig from a few years back. The gig was a fantastic experience and the recording kicks ass, so it would have been a shame for it never to be released. It’s thirty years since the release of Strive, so it’s perfect timing.

Kevin Hunter: By "the second time" are you referring to the limited edition vinyl LP as the first reissue? This is only the first reissue on CD; the original OLI CD was released because the format wasn’t around in 1983, so that wasn’t strictly a reissue, just a release on a ‘new’ format. With regard to shelf-life of releases, it depends upon the artist, surely? Bowie and the Beatles still sell to new generations of listeners. Music is probably more disposable insofar as consumers can just pick and choose tracks to download, whereas at one point you had to be content with a single or spend your hard-earned money on an album and take a gamble on whether it was going to be worthwhile or not. But to me that was part of the enjoyment – you’d buy some great albums but also a few real turkeys on the way. Music doesn’t come with guarantees. It’s up to the listener whether they want to be reminded or to buy into the past, and often it’s the record companies who decide on whether to reissue something, isn’t it?

Is this a precious record to you? Is the reissue for the kids or the completists?

CL: I’m sure it’ll get picked up by people who weren’t even born when it originally came out, and for me it was our finest hour.

KH: Precious? It’s certainly an important record to me, because it’s the only Flux album I’ve played on and been part of – but I think it’s a great piece of work and it sounds a lot more punchy than the first CD version. That always sounded a bit lacklustre to me. It’s available to anyone who wants it, for whatever reason.

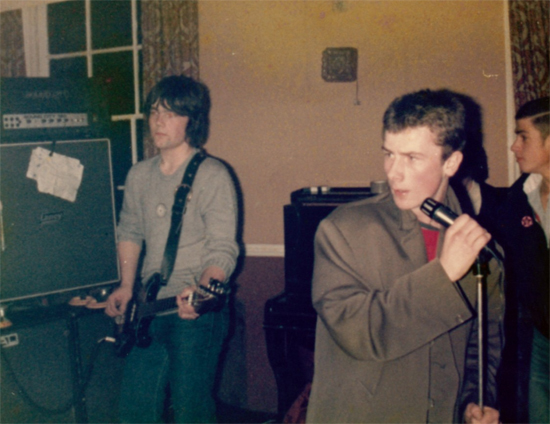

Did you listen to much music, other than what your friends were doing, when you were making your first record? I hear lots of things that remind me of primitive US hardcore bands in Strive, much more than I do with other anarcho bands of the time.

CL: I can’t remember buying records by anyone at that time, or listening to the radio, so I guess I only listened to bands we played gigs with. The only influence other than the obvious one of Crass would have been Rema Rema and their love – like me – of feedback. My ears are paying for it now!

KH: Personally, I listened to pretty much anything but anarcho stuff at the time of Strive, although I thought The System were really great. Far more listenable than the majority of UK anarcho bands. I did hear some US bands, I bought Flipper’s Ha Ha Ha single after hearing Peel play it, and I loved it. In the main I preferred hook-based songs, and I was into UK bands such as Wasted Youth, Southern Death Cult, Danse Society and Bauhaus. I loved the fact that Danny Ash of Bauhaus got weird squealing sounds out of his guitar. He also looked fabulous, but that’s by-the-by.

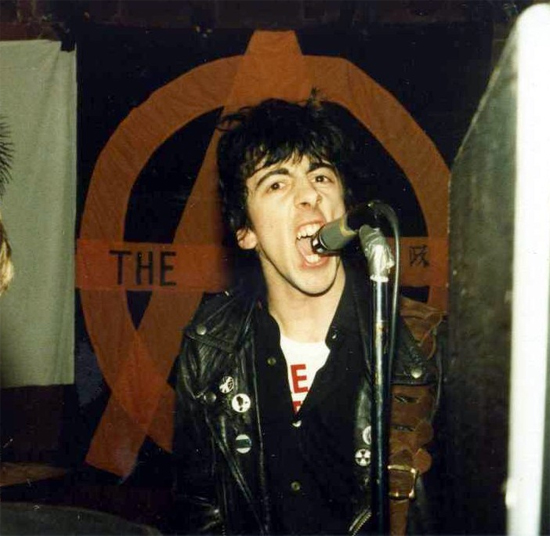

How did it work playing such aggresive music telling people not to kick each others’ heads in? Did the message ever get distorted, as more different kinds of people came to your shows?

CL: It was the time, there was a lot of aggression around and a lot of things to be angry about. Looking back it wasn’t good, but it seemed normal at the time.

KH: I don’t remember that much violence rearing its stupid head at our gigs, although the gobbing really fucked me off big time. I hated that… I never really understood why we got gobbed at, because we weren’t that kind of ‘punk and disorderly’ type of band. Apparently it was pretty much de rigueur at those gigs.

Have you ever worried that the idea of your band – rather than what your band actually is – could become a fashion accessory? We all see kids in band t-shirts who probably don’t know that band’s music.

CL: That too sums up the changes since the 80s. It doesn’t bother me too much.

KH: I’m not precious about it, but then I didn’t create the logos. Maybe if someone sees a Flux t-shirt, they might investigate the music, who knows? But if anyone likes the imagery for purely aesthetic reasons, that’s okay. It doesn’t really bother me.

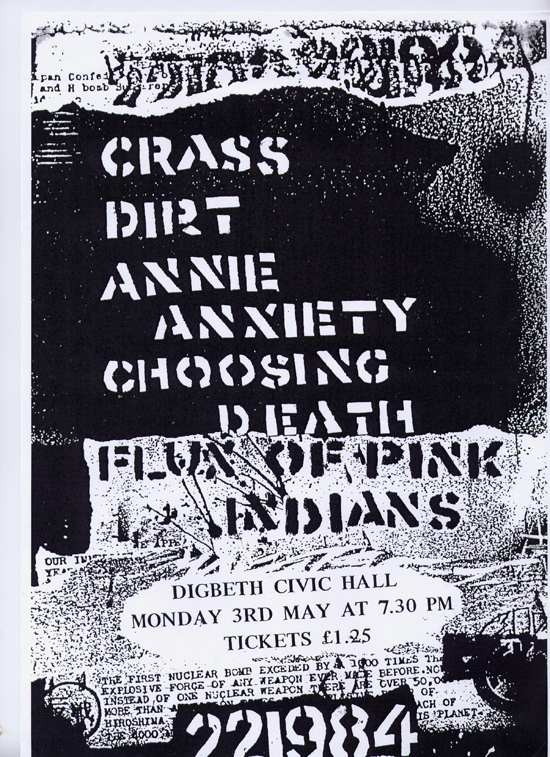

Feature continues below flyer

To what extent was the album remastered? Why do people choose to remaster things? Is it to bring the recording up to date with current technology? Was Neu Smell remastered with [original producer] Penny Rimbaud’s blessing?

CL: I guess remastering takes advantage of advances in sound technology. It’s not essential, and I like the idea of something being exactly as it was originally meant to be. To be honest, I haven’t been involved with that side of the re-release so I can’t say more. As far as I know, Penny knows nothing about it being released again, and I doubt he would care.

Cass Irvine [of Wired Masters]: We re-mastered the album direct from the original analogue tapes. This was ideal, as we captured the audio at 24 bit/96kHz – a much higher resolution than the 16 bit/44.1kHz, which is what you get on a CD – where we might otherwise have had to source the tracks. Of course we still have to go back to 16/44.1 for the new CDs, but the important thing to remember is that analogue to digital converters are much better than the ones from the 80s and early 90s. Digital technology was in its infancy then and consequently the converters sound terrible.

This is one reason you might want to re-master, especially with older recordings that were digitised to CD in the 80s and early 90s. Music got so much louder and brighter over the years; the so-called ‘loudness wars’. Sometimes you might want to re-master an old record to get a more contemporary sound, so that’s another reason. If you listen to a lot of 80s records the sound is really sterile and there’s a distinct lack of bass, but that was the sound of the era and part of that’s down to the technology, the SSL desks, digital synths and drums and so on. I suppose a reversal from the warm, fuzzy sounding records of the 70s.

Generally, are albums too long?

CL: Impossible to say. If it’s good it could go on for as long as possible, but the early punk albums were great because they crashed in, said what they had to say, and that was that. No filler.

KH: I started buying albums at the tail end of the 60s and continued to buy them throughout the 70s until the present, and the majority of albums played for around the 45 minute mark. That’s usually plenty. I’ve got albums that sound really short, even though they’re 45 minutes long, just because they’re so good and I don’t want them to end, but probably if they’d been stretched to an hour or more they wouldn’t have the same impact. But then I’ve got quite a short attention span.

Upon the original release of Strive you said that music wasn’t a way of life for you. What was your life at the time, and was music ever a way of life? Derek has the label, is music a way of life now?

CL: No, the music wasn’t a way of life for us, but it was the core of what we did. The music allowed us to meet people and to get around the country. I’m not a fan of the music business, and was happy to walk away when One Little Indian was up and running.

KH: When Strive was released I’d already left the band and continued with my day job. I was working as a printer and paste-up artist, so music definitely wasn’t a way of life for me, certainly not as far as playing an instrument went. I would have liked to continue being a musician but I was never that proficient at playing guitar, so it wasn’t an option.

When an indie label has massive artists signed to it, how does it remain independent?

CL: Couldn’t say as I don’t listen to music! Sorry!

Are there any more Flux projects in the pipeline? Are you still in touch with Adrian Sherwood?

CL: Can’t see anything getting released any time soon. We were lucky to bump into Adrian Sherwood in the early 80s and he certainly influenced our last album, Uncarved Block. It’s a great album but was Derek’s project, and once it was released most of us went our separate ways.

What were you listening to at that time? I always imagined you being into Test Dept. around then

CL: I got into bands like Tackhead, Swans, Mutoid Waste System, World Domination Enterprises… Anything noisy.

Did you have to re-learn the record for the live shows?

CL: Certainly did, but I’m lucky enough to be self-employed and I played the album over and over again in my workshop. The first rehearsal was crap and a real wake-up call. By the time we played we’d got it right, we all made a few mistakes but it sounded great. It felt like it only lasted ten minutes. Shame we didn’t get to play my favourite Flux song of all time, ‘Is There Anybody There?’ It was too difficult to nail. Tant pis!

KH: I hadn’t picked up a guitar much between 1988 – three and a half years after I’d left Flux – and 2007 when we were approached to play the Feeding gig, so I had to go through the album a few times to remind myself what the chords were! But I knew the songs themselves very well indeed, so it wasn’t a case or re-learning the material so much as re-familiarising myself with where to put my hand on the fretboard. They’re not very complicated arrangements though, so it wasn’t difficult.

Flux Of Pink Indians’ reissued and remastered version of Strive To Survive Causing Least Suffering Possible is out now via One Little Indian