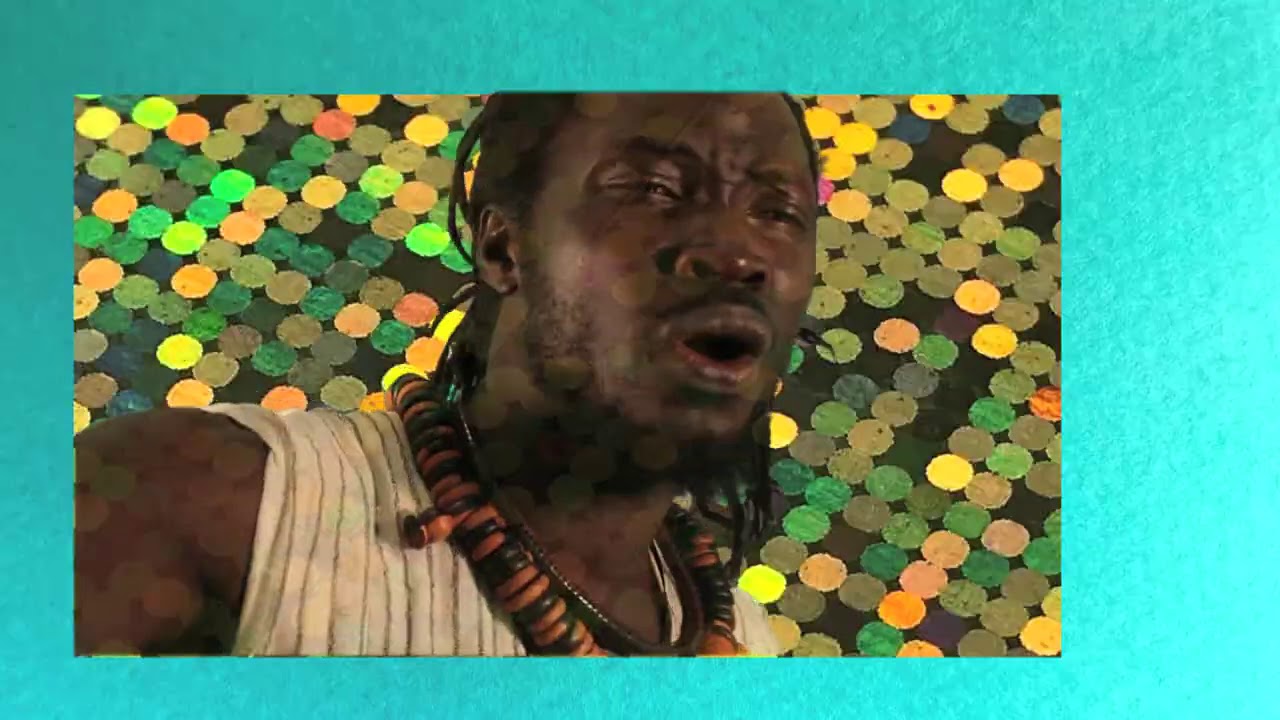

Photo by Guy Bolongaro

“When you go into exile,” says Falle Nioke, “you are going with a mission. My mission was the music.” He is speaking to tQ about his decision, shortly after dropping out of school, to leave his family in Guinea and join a nomadic band of musicians, playing primarily across Senegal. From the age of eight he had been fixated on becoming an artist after seeing Guinean and Malian musicians like Sory Kandia Kouyaté, Amie Koita, Salif Keita, and Mory Kanté performing on a television program, a fixation he would never let go of. His entire life since has been dedicated to his art, despite what challenges it might bring.

His parents were less than keen for a start. “They didn’t want me to do music. They thought being a musician was just drinking and smoking.” Nioke and his family are Coniagui, among the smallest of Guinea’s 32 ethnic groups. “Other tribes have the music of their culture, but my parents said that in my tribe there were no artists. They wanted me to go to school, be a doctor, or work for the government.” Nevertheless, growing up in a military camp – his father was a soldier – Nioke was constantly mixing with friends from other cultures like the Susu and Mandinka, and absorbing their music. “I remember myself at the age of 12, dancing and miming to everything.”

In his teenage years, while his father was fighting in Liberia, Nioke was sent to live with an uncle in the countryside. Moving from the relative luxuries of the military base was an upheaval. “I’m used to electricity and tap water, when I went there there’s no electricity, and if I want water I have to go to the well.” In addition, his uncle was strict when it came to music, “he told me ‘there’s no music here. You go to school, after school you do your homework, and in the morning you go to school. That’s it.’” But Nioke kept rebelling. He would sneak down to the riverside with his friends and sing for them. “When I sing they’d say ‘wow! Falle, this is good! There might be something in it one day!’” During his schooling, “I was singing the whole time.” He ended up failing his university entrance exams twice over and left for Senegal not long afterwards. “I thought, ‘if I’m stuck here, I can’t do what I really want.’”

Senegal, which borders Guinea to the northwest, was close enough to Nioke’s birthplace that he could return in case of emergency, but far enough to satisfy an inherent curiosity. “I wanted to move to another country to go and learn something else.” Back in Guinea he had befriended a group of nomadic musicians, who had encouraged him to join them over the border. “We paid the rent and fed ourselves through the music,” Nioke remembers. “In the morning, you wake up, sometimes there’s no breakfast, so we go out with our instruments instead.” Playing a mixture of hits from West African artists and their own compositions, with Nioke playing traditional instruments the Gongoma, Bolon and Cassi, they’d busk for tourists on the beach, or for traders in the market, who might give them some food for their stall in return for a performance to attract customers. It was a lesson in adaptability, acceptance, and cooperation, Nioke says. “You have to close your feelings and accept anything that comes and just be cool. It’s like if you’re selling food, if you talk to people badly, no one will come to you.”

Photo by Charlotte Player

Occasionally, they’d drift over Senegal’s northern border into Gambia, but frequently encountered issues with immigration. “To stay there you have to pay for an ID card, and we struggled to pay that money.” He spent short stints in prison as a result. After a while, he was “fed up” with the financial barriers, and started hand-making soap and selling it in the morning, playing in the afternoon, until he had money for an official ID for one year.

One day in 2016, Nioke was in The Gambia when his friend and fellow musician Omar back in Senegal got in touch. A British photographer called Charlotte Player had been asking after Nioke – the two had met on the beach there three years previous while she was on holiday and she had a picture of him on her phone. He remembered her well. “I said, ‘oh, Charlotte!’ I asked where she was living, but he said he didn’t know, they just met on the beach.” Coincidentally, that very night, Omar’s band had a show at the hotel where the woman was staying, and he arranged for the two to reunite. “It was such a joy, that day.” Within a year, Player and Nioke went back to Guinea together and got married.

They decided to move to the UK. At the airport, saying goodbye to his family and friends, Nioke was in tears. “My first thought was that I might not see some of these people again, what if somebody passes away while I’m gone? It’s hard not to think about how you’re going to cope in a place you don’t know anyone.” They moved at first to London, and then to Margate where Player encouraged Nioke to keep up his art, and reassure him when he expressed doubts about whether the traditional African music and reggae he had played in Guinea, Senegal and The Gambia would translate to a British audience. Nioke found work in a bar called The Sun Deck, where to his surprise he would hear the same musicians that inspired him on TV as a child back in the army camp. “Lots of different DJs would come there, and sometimes they’d mix stuff like Oumou Sangaré and Salif Keïta. I thought, ‘wow… these are the kind of things people here like?’”

One night, he and Player went out to the Tom Thumb Theatre, an arts venue in Margate, where they met the Swedish ex-pat Johan Hugo, a musician and producer with a number of artists, including African acts like Baaba Maal and The Very Best. They ended up working together in Hugo’s studio on a couple of slick singles, ‘Salia’ and ‘Taimedy’, which placed Nioke’s vocals front and centre. They then caught the eye of James Greenwood, aka Ghost Culture, who told Nioke he’d like to work with him too. They released the Youkounkoun EP – which is named after Nioke’s hometown – with expansive electronic beats proving the perfect base for Nioke’s flowing voice. His first time working with electronic music, it took him far out of his comfort zone, but he was keen to experiment. “When I got here to England, people loved these styles. So I thought ‘OK, I’m going to test it out, and try and fit in.’” Another fan was Hugo’s fellow Swede Joel Wästberg, aka Sir Was. He worked with Nioke too, on two 2021 EPs, Marasi and Badiare, which rely more heavily on Nioke’s own established styles but augment them with subtle and delicate production.

All three of the projects are quite different from one another. His work with Hugo feels embryonic and straightforward, like a figuring out process. The Youkounkoun EP exists firmly in the middle ground between the two artists, while Sir Was brings out Nioke’s tender side. “The Sir Was thing, that’s the kind of music we did with my friends. Then with Ghost Culture, the vocal is me, but I try to fit in with the rhythm he was doing.” If nothing else it showcases Nioke’s sheer versatility. His voice can be deft and razor sharp, as it is on Youkounkoun, and it can also be extraordinarily soulful, as on the Marasi and Badiare EPs.

Photo by Charlotte Player

Across that smattering of releases, Nioke sings in seven different languages including French, English, Susu, Fulani and Malinke. He makes a special point, however, to sing in Coniagui, the little-spoken language of his own small ethnic group that is rapidly being phased out under governmental pressure. “I have learned many different languages, but when I think about [Coniagui] I feel sad,” he says. “I see my own people telling their kids, ‘You can only speak French or English in my house’. If you can’t speak French or English, people will laugh at you thinking ‘he didn’t even go to school!’ You can’t go out to a party, because they’ll only speak French. My tribe is the smallest in my country, and if you go into their village you’ll hear most people speaking French because most of them are Christians.” There are Coniagui in Senegal as well as Guinea, but there, “you’d see them and think they’re just Senegalese. They have to tell you ‘I’m Coniagui’. That’s what I’m trying to do in my music. I want to fight those ideas, to let people know that it’s good to learn, but it’s bad to forget your own roots.”

It’s a mark of Nioke’s abilities as a songwriter, that his music can span styles and languages so deftly, while also exploring themes that are universally applicable. Whether in Guinea, Senegal, The Gambia, London or Margate, he’s written songs the same way. “I take my time to listen, to mingle with people, sit down and watch.” His own eventful life story informs his songs, but he extracts the universal emotions contained therein. Nioke’s most beautiful song, ‘Wonama Yo Ema’, translates roughly from Susu as ‘don’t look down on people’. "If you help someone who is poor or in need, don’t judge them or spoil their name in the community," he explains. His most hypnotic, ‘Rain’, is based on an African proverb about how “the rain comes for everyone,” providing a lifeforce to the world

He’s always been drawn to water, in one way or another. His favourite place to write is Margate beach. It reminds him, he says, of sneaking off down to the water in Guinea to sing and rehearse under his family’s noses when he was a boy, and of his performances to tourists as he and his travelling band of musicians tried to make ends meet in Senegal. Perhaps its no coincidence that his friend Omar bumped into Nioke’s future wife on the beach too. “I love the sea. It’s the place I can go to free my mind. Back home it was the place I could go and sing without anyone telling me to shut up. It’s where you see artists all over, singing and creating.” When he and Player were first looking around, considering their move from London, “I saw the sea and said, ‘I love this place’.”