The Duke Quartet (courtesy John Metcalfe)

From 1989 until its demise in 1992, cult Manchester label Factory Records, famously home to Joy Division, New Order and Happy Mondays, issued 14 albums on its obscure classical imprint. The slim but notable catalogue of Factory Classical mixed work by modern composers (Steve Martland, Graham Fitkin, Walter Hus) with artist-led volumes dedicated to historic figures (Handel, Monteverdi, Mozart) and albums showcasing performers who mixed sources old and new.

Despite plenty of initial favourable press interest, the sporadic nature of Factory Classical’s output led to reduced public awareness, while its parent company rode the runaway train of the Happy Mondays and Madchester into the sidings of drug abuse and financial disaster. Treated as little more than a footnote in later biographies of the label (including my own for this site), here we tell its story album by album, speaking to almost every artist who recorded for it.

Factory Classical’s first wave of albums was co-ordinated by John Metcalfe, viola player for semi-classical Factory act The Durutti Column as well as imminent label signings the Kreisler String Orchestra and the Duke String Quartet. “I was a relatively angry young man at that time,” Metcalfe says, “and chose to channel some of that into a rather naïve disapproval of standard classical industry practices. The white tie and tails and very, very boring, reproductions of Constable paintings on album covers, all that stuff. I remember talking to [Durutti Column drummer] Bruce Mitchell and said, ‘Had Factory ever thought of doing classical music?’ He said, ’I’m sure Tony [Wilson] would be open to it, go and talk to him.” So I had a chat with him and he said, ‘Off you go mate, fill your boots.’ I don’t think anyone at Factory knew anything much about classical music, where to go or who to approach or how all of that stuff worked. To be honest I didn’t have that much idea either but I think I was, not just the ideal candidate, but the only candidate for the job.”

Kreisler String Orchestra – Kreisler String Orchestra

The label’s first five eponymous releases turned up in shops simultaneously in September 1989. Factory partner Peter Saville oversaw the artwork for the first batch, delegating each record’s cover image to a different designer. Regular Saville collaborator Trevor Key shot the photo of the Kreisler String Orchestra, a large ensemble of which Metcalfe was a member. “It was pure nepotism on my part with Kreisler and the Dukes as I was in both groups at that time,” admits Metcalfe.

The bulk of the Kreisler’s lone album is taken up with two works by Benjamin Britten, his ‘Simple Symphony’ (1933/4) and ‘Variations On A Theme Of Frank Bridge’ (1937). The accessibility of the former, serves as a sensible choice to open the Factory Classical project, its four movements easy enough on the ear for non-classical consumers to get a handle on. ‘Playful Pizzicato’ carries a similar bucolic revelry as the theme from ‘The Archers’, ‘Frolicsome Finale’ that of a 50s Hollywood Western. The Frank Bridge variations serve to expand new listeners’ understanding of the potential of a string orchestra further, running through a range of moods, from frantic to romantic.

Separating the Britten works is the intense repetition of ‘Cartoon’, a 1984 piece by Serbian composer Zoran Erić, the Kreisler’s most challenging but rewarding piece, and the album ends on a gentle farewell with ‘Wir Wandelten’ from Brahms’ Opus 86 of 1884. Only the enthusiastic sleevenotes by ‘philistine and convert’ Mark Webster let the project’s opening chapter down, his effort to win over the youth with talk of the Kreislers as ‘Classical hip hop. B-Boys and Girls’ trying a little too hard.

Robin Williams – Robin Williams

Housed in the only colour sleeve of Factory Classical’s first set, courtesy of photographer Phil Cawley and art director Trevor Johnson, Robin Williams’ thoroughly gorgeous set of oboe pieces was the most accessible of the initial albums.

“Robin I knew from college,” says Metcalfe, “I thought of him just because he was and still is an amazing player. He had the most exquisite sound of any oboist I knew, so I asked him and he was up for it.”

With the exception of another work by Britten, the classical Greek portraits of ‘Six Metamorphoses’, all Williams’ performances here are accompanied by pianist Julien Kelly. Surrounded by sonatas by Francis Poulenc and Paul Hindemith, Williams’ solo Britten pieces are some of the album’s most evocative pieces, the listener easily able to conjure up the mythological figures of the titles (lively Pan, sorrowful Niobe).

“Most of us were very poor students just out of college so the notion of making a record ourselves didn’t really exist,” Metcalfe points out. “I think everybody jumped at it because there weren’t that many independent classical labels who were looking to find a new audience, they were just looking to fill gaps in the repertoire. I don’t think anybody got paid but classical has always worked slightly differently, because unless you’re a Pavarotti or an Itzhak Perlman you don’t make money from your CD sales. There are very few royalties but the CD gets you coverage, gets you reviews and gets you noticed and then more people come to your gigs.”

Perhaps the most recognisable moment of Williams’ album comes at the end. ‘Prelude And Variation’ by Theodore Lalliet is better known to generations of schoolchildren around the world as ‘My Hat It Has Three Corners’, a banal yet mind-bending tune forced into many an infant’s ear in music class.

Duke String Quartet – Duke String Quartet

Factory Classical gets more serious from now on, with Metcalfe’s other project, the Duke String Quartet, splitting the two halves of their album between works by Shostakovitch and Michael Tippett.

“We thought we were fairly adventurous at the time,” Metcalfe says. “We earned most of our money doing gigs for British music societies which – and this is not pejorative at all – have a certain demographic. Most of those audiences want to hear some Mozart and some Beethoven and we had a hard time actually even selling Shostakovich to them. I remember one music club promoter said, ‘Our members don’t like Shostakovich,’ and I said, ‘Well have you had any?’ And he said, ‘No but they’re put off by the number of consonants in the surname.’ We would also get the odd letter to our manager complaining that we wore boots instead of proper concert shoes and somebody once sent a dress to our leader Louisa (Fuller) which was this unbelievable bright green thing made out of curtain material. They just didn’t get it. We were always fighting and struggling but no matter how hard we tried we were on a sticky wicket.”

Dropping the ‘string’ from their name, The Duke Quartet would go on to become probably the most widely heard artists to record for Factory Classical, thanks to their appearances on albums such as Blur’s ‘Parklife’. Metcalfe looks back on their debut with affection. “We went off to a friend’s rundown house in the country. It was a little bit Withnail & I, we just put some stuff in the back of a van. I remember Tony making the effort to drive down a very long muddy lane and turning up in the middle of the night to check out what we were doing. We edited it on a very early editing system but the guy we took it to looked at it through his oscilloscope and said, ‘You realise it’s completely out of phase?’ so we chopped it up and put a bit of reverb on it, because the actual room itself sounded terrible. We had fun but it was very serious work as well. It was a good record.”

Metcalfe continues to release his own records (most recently The Appearance Of Colour on Peter Gabriel’s Real World label) and arrange strings for acts including Bat For Lashes, Coldplay and The Pretenders.

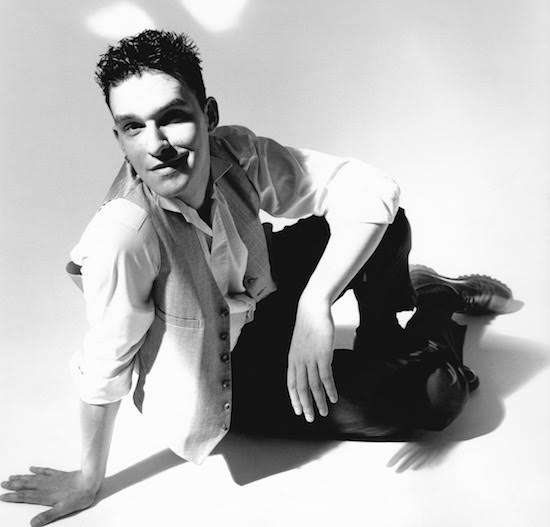

Rolf Hind – Rolf Hind

Portrait courtesy of Johnny Greig

With the first of pianist Rolf Hind’s two albums for Factory Classical, all bets for easy listening classical recordings are off. This solo debut is a tour de force of challenging 20th Century composition, beginning with the dazzling cross-cut planes of Ligeti and continuing through Oliver Messiaen, Elliott Carter and Liverpudlian composer and label mainstay Steve Martland.

“I’d had a conventional training as a classical pianist with all the standards, but pretty soon gravitated to working on new and recent music,” says Hind. “I’d never heard of Factory but I played pieces I felt really comfortable with and loved. I liked the challenge, as well as the opportunity to work with living composers, some of whom were big and colourful characters.”

Martland’s 1982 piece ‘Kgakala’ is the most interesting piece here for the lay listener, with Hind’s left hand sending out rippling clutches of bass notes that could have emanated from the pulsing analogue synth banks of the early Human League or Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark. “Steve’s piece is hard,” Hind agrees, “But no more so than a lot of music written for piano. There are Finnissy pieces on ‘Country Music’ (below) which are almost unplayably fiendish.”

Intelligently sequenced, the rapid clashes of the initial Ligeti pieces flow imperceptibly from composer to composer, the energy emptying out into the leisurely ambience of the Messiaen and Carter pieces. It’s one of the very best albums of the series.

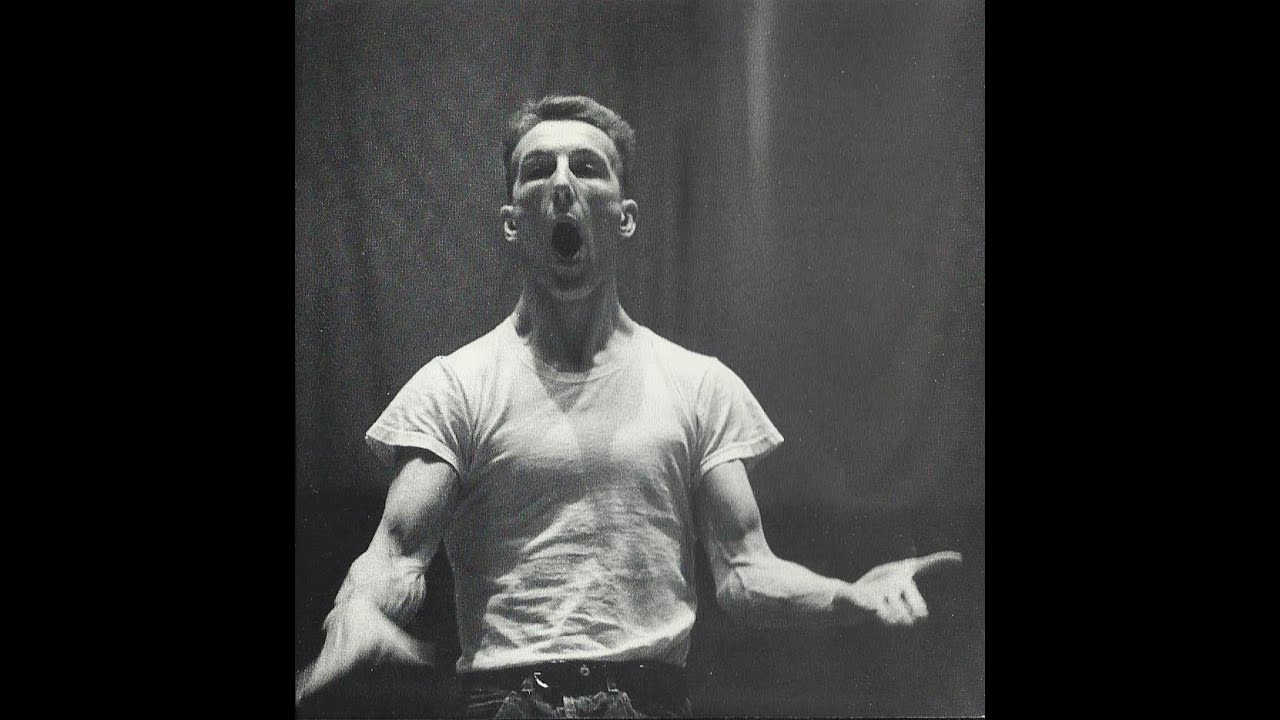

Steve Martland – Steve Martland

From its striking cover photo (the composer, bare chested) inwards, the first of Steve Martland’s three Factory albums demands to be noticed. The album’s first half ‘Babi Yar’ sets three orchestras crashing against each other, a cacophony of stabs, blasts, bells and gongs, grappling with the Holocaust as it references the horror and confusion of the massacres perpetrated by the Nazis in the ravine, near Kiev, of that name.

The album’s second side, ‘Drill’ presents the mechanistic playing of two performers hammering away at a pair of pianos for nearly 30 minutes. As with every Martland release, the sleevenotes carry the legend ‘This recording should be played at high volume.’ It’s an incredibly powerful album.

Despite the critical and musical success of Factory Classical’s first year, Metcalfe’s association with the label began to unravel. “I went to a meeting in Factory’s old Palatine Road offices and Tony and [Factory’s general manager] Tina Simmons were there, and there was this bloke sitting in a chair who was introduced to me as the guy who was going to take over the label. I was in deep shock. What I should have done is chucked the table through the window or just gone completely fucking mad. Maybe Tony would have liked that and said, ‘Well I can see that that this matters to you’ but I think I was just too young and still relatively shy. It was a chap called Stephen Firth who took it over. We had this pretence, a little dance, where I would carry on suggesting certain projects to him and he paid lip service to them but I think essentially he went on and did his own thing.”

I Fagiolini – The Art Of Monteverdi

Factory Classical’s next albums appeared in another group of five a year later, in September 1990. Art direction was passed over to the accomplished Bill Smith Studio with photography for each sleeve by The Douglas Brothers.

Also marking out Factory Classical’s second year was a new emphasis on vocal works. I Fagiolini brought to Factory the first of the ensemble’s long-running series of interpretations of baroque composer Monteverdi.

“I had a good relationship with Stephen Firth but I can’t remember how Factory contacted us,” considers I Fagiolini’s director Robert Hollingworth. “It’s possibly because we had just won the Early Music Network’s Young Artists competition.” While I Fagiolini also worked with modern composers it was in the field of Early Music that they would become most identified. Hollingworth recalls performing the work of, “French and English composers – John Wilbye, Thomas Weelkes, Clément Janequin – all of whom we’ve since recorded, and Monteverdi’s contemporary Giaches de Wert. But Monteverdi spoke to me emotionally, incredibly strongly, and still does."

"The Art Of Monteverdi is the first in a series of recordings they are to release with Factory Classical", claims the sleevenotes, although I Fagiolini’s subsequent albums would appear on other labels. “The planning side of things was difficult with Factory,” Hollingworth admits, “We were thrilled to have been involved but the Monteverdi recording I’m most proud of is the Other Vespers we’ve released on Decca Classics, to say nothing of the three we did for Chandos back in the noughties. I’m still finding pleasure and interest in his music all these years later. All those stemmed from our initial enthusiasm about Monteverdi that Factory allowed us to indulge.”

Rolf Hind – Country Music

Like his debut, Hind’s second Factory Classical album drew from the pool of 20th Century composers, but here he worked around the theme of the title. This isn’t country music in the Nashville sense of the word but in an older way, meaning music from the British and European countryside.

Beginning with the jaunty arrangements of Australian born composer Percy Grainger (also responsible for the familiar schools’ version of ‘English Country Garden’), Hind soon ventures into more abstract modern pieces by England’s Michael Finnissy, Scotland’s James MacMillan and older work by Janacek (Czech) and Bartok (Hungary). The latter’s disturbing, nocturnal pieces that make up ‘Out Of Doors’ are the album’s most effective.

After two decades out of print, Hind’s albums were re-released by Heritage Records in 2013. “I’m very proud of them,” he says. “It was a fantastic punt by Tony Wilson to have artists genuinely represented by the music they played rather than moulded into any shape by market pressures. Unprecedented I think.”

Red Byrd – Songs Of Love And Death

Courtesy of John Potter

With better promotion, Songs Of Love And Death could have broken out of the Factory Classical niche. Like I Fagiolini, vocal collective Red Byrd presented a handful of songs by Monteverdi, interspersed with pieces by Brian Elias and Frank Martin and specially commissioned work by former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones and Harvey Brough (formerly of jazz revivalists The Harvey Wallbangers).

“The great thing for us was being given a completely free hand by a label that made no distinction between genres – it was all just music,” remembers John Potter, one of Red Byrd’s core duo alongside Richard Wistreich. “No one else would have touched a recording that had old and new music in it, let alone old music that used electric instruments.”

While this yields mixed results (Martin’s setting of Villon’s ‘Trois Poems De La Mort’ benefits little from the electric bass and guitar intended by the composer), Jones’ ‘Amores Passados’, a trio of love poems, reveal themselves to be among the most beautiful music Factory Records ever released.

“One of the Red Byrd agendas was to ask rock musicians to write for us if they felt they had could devise something that would work in our neck of the woods,” elaborates Potter. “John Paul was brilliant – he quickly realised that 17th century figured bass lines were no different from a rock chart and he took a lot of trouble discovering what the instruments could do. We offered him electric instruments but he chose to go for lute, harp and lirone.”

Also of interest is the final song ‘The Red Bird’, an ecological lament penned by Brough, with lyrics by television presenter and writer Emma Freud. “Harvey is an old mate of mine and Richard’s and we often found ourselves working together,” says Potter. “Emma was his girlfriend at the time and the two of them were very much into environmental issues, hence the text. Harv worked the drum machine, a novelty back then that we also used in Sting’s ‘They Dance Alone’, which we used to do as an encore.” Had it been released as a single ‘The Red Bird’ would have fitted right in with such bona fide Factory acts as Durutti Column and To Hell With Burgundy. Which may not have guaranteed much success but would serve to remind fans of Red Byrd’s forward thinking efforts.

“We were incredibly lucky – privileged really – to have the Factory experience,” Potter says. “If we could have invented the ideal record company that would have been it: they represented our artistic aims exactly. Red Byrd went on to make a dozen or so albums mostly on Hyperion, but they are all dedicated early music albums. We never managed to persuade anyone else to take an album of both old and new. We tried for years to get the rights to Songs Of Love And Death so we could re-release it but the whole thing got lost in some kind of legal limbo.”

Graham Fitkin – Flak

Courtesy of Steve Tanner

After Steve Martland, pianist Graham Fitkin was the best known and most acclaimed of Factory Classical’s modern composers. “I was approached after my group of four pianists at two pianos had performed in Stockton on Tees, where I was composer in residence at Dovecot Arts Centre,” Fitkin says. “I was good friends with Steve Martland on the label already – we studied in Holland together where I’d lived as a student with Louis Andriessen – and was aware of John Metcalfe’s involvement and Tony Wilson’s of course. Someone at Factory asked me to send tapes of the band to them and a plan was hatched to record my work for the group.”

The album’s first half involves four performers playing simultaneously on two pianos, a robotic mesh of cunning systems music, less jarring than the Ligeti pieces previously offered by Rolf Hind but still a challenge of focussed listening. “The three other musicians on the album (Eleanor Alberga, Shelagh Sutherland and Errollyn Wallen) were fantastic pianists,” says Fitkin. “It was at a time when many pianists with that sort of technical ability weren’t used to playing either minimal or groove based musics. These guys understood how I was writing and it didn’t faze them if one player was in five in a bar, another in four and another in seven at the same time.”

The album’s remaining pieces are solo piano pieces, more ambient than the arresting opening half. “There was talk about mixing the fast, information rich, multi-piano works with the slow, bare, solo pieces, but I was clear that I preferred to have two distinct blocks on the disc,” says Fitkin. Even so, ‘Flak’ (later reissued by Fitkin’s own label) represents another crucial Factory Classical release that deserves to be remembered alongside its parent label’s finest moments.

“It was a big boost to my profile and unusual too,” he says, “Because at that time many composers at my stage of development found a career path through the classical side of publishing. I never wanted to do that and this gave me added incentive that I didn’t need to go down that route. I was expecting to record another album with them soon afterwards but, as we all know, the label folded.”

Erik Satie – Socrate

Perhaps the most widely acclaimed of Factory Classical’s historic releases, Socrate saw Music Projects/London perform Erik Satie’s lesser known classical Greek cantana of 1918. Three singers, Susan Bickley, Eileen Hulse and Paricia Rosario, took on the four roles of the French-language script, accompanied by orchestra directed by Richard Bernas.

“Music Projects/London’s repertoire was deliberately inclusive and open-minded,” reveals Bernas. “We worked with a wide range of living composers, with few if any stylistic restrictions, pretty much everyone from John Adams to Iannis Xenakis. So Satie was the anomaly, though I was very fond of his work and had recently conducted Socrate for the Almeida Festival. We were really fortunate with the singers, all of whom I had worked with before and all of whom went on to important careers. It was essential that the diction and accent of the performances was impeccable, as Satie’s treatment of the text is central.

“The recording was made in an ex-church at Petersham, Surrey which I knew from previous sessions and had very good acoustics, especially for voices and medium-size ensembles,” he continues. “It was used a lot by Decca until the Heathrow flight path made that impossible. The recording team weren’t part of Factory, they were contracted in, but they were first rate. So this was far from an indigenous Factory product, but during the CD boom of the 80s that’s how a lot of stuff was made.”

The remainder of the album consists of shorter pieces for vocal and piano, more recognisable as Satie works to those familiar with his proto-ambient ‘Les Gymnopédies’. Unless you speak French, only the sleevenotes’ English translations let on just how comical the original poems were. Note also that Socrate is also the only Factory Classical release to date to be re-released by LTM Recordings, the specialist reissue label run by Factory biographer and fan James Nice.

“It’s a shame that Satie has become a one-tune composer,” Bernas points out. “The Gymnopédies are totally over-exposed and everything else is ignored. Yet a great deal of his music is of a similar quality. As far as I can remember Factory hit the skids before more could be done.”

Piers Adams – Handel Recorder Sonatas

Come 1991, only two Factory Classical releases appeared, both in July. Artwork was now in the hands of Factory’s recently appointed in-house designer John Macklin, who continued initially with the albums’ uniform branding. “Saville described how we were presenting classical musicians like other Factory bands,” remembers Macklin, “Begging the question why have a separate label at all, which he couldn’t readily answer. Factory’s decisions often seemed instinctive rather than calculated, which was probably partly true but was also the persona that Tony enjoyed presenting to the world.”

The most straightforward of the pair was an album of Handel sonatas by virtuoso recorder player Piers Adams. Accompanied by cellist David Watkin and harpsichord player Howard Beach, Adams trilled and piped his was through seven Handel sonatas, and one additional composition, the ‘Harmonious Blacksmith Variations’.

Although technically impressive, the sheer amount of pieces here induces fatigue, but attention should be drawn both to Beach’s chamber organ work on the ‘Sonata In D Minor’ (a piece originally written for flute, as Adams’ sleevenotes explain) and the complex adaptation of the ‘Sonata in D Minor, Opus 1 Number 1’, originally intended for violin.

Walter Hus – Muurwerk

Works for strings had been absent from Factory Classical’s output since its initial run but they returned on Belgian composer Walter Hus’ strong Muurwerk.

“To be honest, I didn’t know Factory at all,” says Hus. “I came from the classical music scene and when my horizon broadened it was more into the direction of free jazz, minimal and ethnic music. It was only later on, when I got really interested in rock and techno, that I was surprised to hear that I had made a record for one of the most mythical labels of all times. Apparently my music had something in its DNA that bridged the gap between classical and rock.”

Hus’ 1st String Quartet takes up the large opening chunk of the album, a strident and angular set of pieces running from the offset time signatures of opening section ‘La Théorie’, through the vertiginous ‘Molto Vivace’ to the closing, clashing diagonal sheets of ‘Liefde’, a piece that finally fades into the tinkling of the music box.

“The Swiss chalet I’m holding on the album sleeve is the music box playing at the end,” says Hus. “It’s a souvenir from early childhood that I remember passing hours of astonishment with. Since I came to the studio from my parents’ house it happened to sit in my bag. We tried it out and that was it. I think putting it on the sleeve must have been a sort of need to bring my own life into the game, the singer-songwriter syndrome.

“But sometime later an Italian friend asked me, what was the signification of ending my piece with the march of the Italian fascist brigades? I had never asked any questions about the tune the Swiss chalet was playing but it appeared to be exactly that. A fascist hymn. I admit that I’m in doubt whether I should have red cheeks or interpret it as some unconscious political message I’d wanted to pass. I’m still figuring out which message that could have been.”

The three sections of the title track close the album, another string quartet composition here arranged for just a trio. In a little over ten minutes the performers run the range from sheer jagged scrapes to plucked gentility to deep bowing bass notes, the world of the string orchestra in miniature.

“After the release of the album I didn’t have any contacts with Factory whatsoever,” Hus concludes. “Our time together had been really too short to lead at anything substantial. I was pretty innocent about career planning, all I wanted was to create the next new piece. Besides, very shortly afterwards I heard that the label had ceased to exist. Maybe my record was the final blow.”

Steve Martland – Crossing The Border

Factory’s final pair of classical releases arrived in July 1992, four months before the company called in the receivers. Both were the work of Steve Martland, absent from the label since the October 1990 release of Glad Day, a one-off EP with former Communards vocalist Sarah Jane Morris and lyricist Stevan Keane, promoted by a dance remix of final track ‘The World Is In Heaven’.

For the sleeves, Macklin dispensed with Saville’s design template, with cover photography for both albums offering mysterious images by Bernard Oglesby. “Bernard was someone that Tony knew,” Macklin explains, “And one day we went to his studio in a derelict warehouse in Stockport. He was making giant photographic prints in a bathtub and we came back with some images that were chosen fairly arbitrarily. The image for Crossing The Border is a surviving fragment of the Berlin Wall but we didn’t know that until later.”

Crossing The Border is perhaps the peak moment of the Factory Classical project (although Martland’s previous album runs it close). The recording of the massed string orchestra on the title track is consistently rich across 24 stirring and uplifting minutes: it’s impressive that, in its dying months, Factory could find the time and expense to fund such jaw-dropping and extravagant music and frustrating that the world didn’t notice.

Of the remaining tracks, the lengthy, percussive ‘American Invention’ and ‘Shoulder To Shoulder’ hark back to the intensity of ‘Babi Yar’, while the succinct, brass loaded ‘Re-mix’ and ‘Principia’ ought to have been released as a single. Note also, the massed ranks of credited musicians on the album include New Order’s Stephen Morris, and Will Gregory, later founding partner of Goldfrapp and leader of his own Moog Ensemble (of which long-time friend Graham Fitkin is also a member). No understanding of Factory is complete without this incredible album.

Steve Martland – Wolfgang

On Factory Classical’s final release, Steve Martland turned, with the help of his music students, towards that titan of musical history, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. “The image for Wolfgang was oddly appropriate, coming from an Austrian church which apparently had a particular connection with Mozart,” says Macklin. “Again, Bernard only told us about this afterwards, so perhaps he was making it up.”

For the twin Mozart Serenades in C Minor (K388) an E Flat Major (K375), the Steve Martland Band consists of eight wind instruments, paired on oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn. Pleasant and evocative of the cold streets of Austria as they are, both sections are a prelude to the album’s ‘Wolfgang’ suite itself, Martland’s own arrangements of operatic arias from Don Giovanni, The Magic Flute and The Marriage Of Figaro. His band perform them, as his sleevenotes explain, in the style of the jobbing groups that wandered from tavern to tavern busking for reward in Mozart’s own lifetime. It stands independent of Martland’s other work but is a curious diversion.

Steve Martland died from a heart attack in 2013. “Steve back then was classified as the Angry Young Man of classical,” remembers Metcalfe, “And he was quite angry about certain stuff.” While Red Byrd’s John Potter found him “cocky and frightening”, Rolf Hind’s memories are fonder. “He was a law unto himself,” he recalls. “Warm, gobby, outspoken, indiscreet. I really liked him.”

Martland’s debut and Crossing The Border were re-released together by Catalyst as The Factory Masters but Wolfgang slipped through the net. Factory called in the receivers in November 1992 and, in the quarter of a century since, some great efforts have been made to ensure that little of its recorded legacy has fallen out of print. Factory Classical’s catalogue is the exception, hard to find but worth the pursuit. As John Metcalfe says, “It’s not, ‘Hey kids, classical can be cool as well’, all that nonsense. It’s a soundworld. Just because the instrument looks this way or you perceive a certain kind of person playing it, put that to one side and listen to the sound of a collection of violins or some brass or acoustic percussion. At the end of the day it’s just sound waves and it’s amazing.”

FOOTNOTES

John Metcalfe is currently recording a follow up to his 2015 album for Peter Gabriel’s Real World label, called The Appearance Of Colour.

Robin Williams is principal oboist for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

I Fagiolini mark the 450th anniversary of Monteverdi’s birth with new album The Other Vespers (Decca Classics), which was premiered live at Glyndebourne for the Brighton Festival in May.

John Potter and Richard Wistreich split Red Byrd at the end of 2015.

Graham Fitkin released two new albums at the start of 2017: Veneer with his nine-piece band and Vamp in collaboration with singer Melanie Pappenheim.

Richard Bernas continues to conduct across Europe and has produced and curated over a dozen events at Tate Modern, including for this year’s recent Robert Rauschenberg retrospective.

Walter Hus’ later recordings include a 2013 EP of Belgian techno classics (including Push’s ‘Universal Nation’ and The Age Of Love’s eponymous anthem) reworked for Decap pipe organ, on Brussels’ Doctor Vinyl label.