Etienne Daho near his West London flat, by Gabrielle Crawford

Released back in November 2017, French pop prince Etienne Daho’s most recent album Blitz was both a reconnection with the melodic ease of his 80s releases and the ushering in of a new direction, an excursion into spectral psych rock.

Despite the intensity of his engagement with his idols, his discreet assuredness and visionary sensibility ensure that he rarely drowns in his pool of influences – even when pilfering the rhythm from The Zombies’ ‘Time Of The Season’ on ‘Chambre 29’.

“You have to mix things together, like in a cocktail shaker – not just music but films, books, paintings, pictures. That’s how you build your world, you see something and you know that if you delve into it you’re going to learn something about yourself” he says.

Two weeks before his first London show in four and a half years, I meet Daho in the recently refurbished salons of the Institut Français in South Kensington, not far from where he has had lodgings for a number of years. I say lodgings as he appears unwilling to commit to a fixed abode, and has also spent periods living in Lisbon and Ibiza, with each location’s essence becoming absorbed into his personal mythology, moving something in him but also being reconfigured by his gaze.

Blitz, from its title down, and largely recorded at Alan Moulder and Flood’s Assault & Battery, gives us Daho’s London. It’s a fluid vision which, in its moments of narcotic reverie, blurs geographical and temporal lines, while totemic locations and works of art loom like lamps in the fog.

2013’s Les Chansons de l’innocence retrouvée already looked to William Blake (born in Soho) – which the singer discussed with us in a previous interview – and Francis Bacon, and our conversation ranged across London themes, places and people that Daho taps into on both albums.

Etienne Daho: It wasn’t the title to begin with at all, the working title was Canyon – this pure, rocky thing. And then there was the Brexit vote, there were several terrorist attacks, and I felt a nervousness in Londoners. ‘Blitz’ was a word that appeared several times in the press and on the radio, and I thought “of course”.

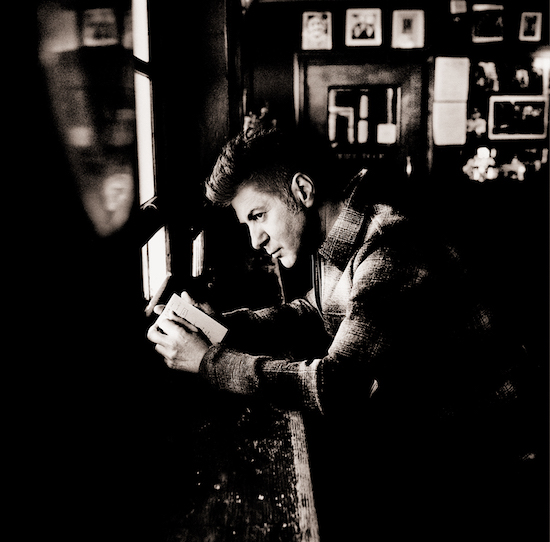

Etienne Daho in The French House, by Richard Dumas

Blitz

What I’m writing is an album that’s at the end of a cycle, with plenty of songs that evoke that, the Apocalypse Of St John. There’s a lot of violence on this album but at the same time it’s full of hope. ‘Blitz’ is one syllable like that (smacks one hand against the other), there’s a lot of energy in the word. So I thought it was the perfect word, the perfect window on to this record. Often when you write, these things impose themselves on you. It was like someone grabbing you by the sleeve and saying, “Do you see?”

“Montmartre où bien chambre à Chelsea" (Montmartre or a room in Chelsea)

ED: It’s an axis between the two. It’s a druggy song, you don’t really know what’s real.

What’s the connection between the two places?

ED: It’s me, I’m the link between them. But it’s true that having lived in Brittany, I always had this proximity to England. I’ve been coming here since I was 14. The first time I came over to work in a hotel in Manchester, they called me a “porter”. I was cocky, I lied about my age and they took me on. I came to learn English and to get closer to the music as I had started listening to pop and lots of Anglo-Saxon music, and my mother allowed me to go for two months. Luckily she didn’t know what I got up to, taking my first tab of acid which completely blew my mind. But she let me go for the work, she didn’t have much money so it was also a way of earning a bit of pocket money.

I didn’t meet any musicians, but I lived with a dealer when I was in London – after the two months in Manchester I came to London all the time. There was the boat from St Malo to Portsmouth and then the train, that was in the mid-70s. It was just before punk took off and it was mostly reggae, there was a big reggae scene. Then the punks arrived, and it was Wire I liked most. They were the ones that really had a sound, something short and intense.

Chambre 29

ED: Syd Barrett is a god for me. I bought Pink Floyd’s first album when I was 12 years old, I listened to it in a shop and it hit me immediately. There’s something of childhood in this music, but more like macabre nursery rhymes. I listened to it constantly, so I think it had a big impact on my musical ear. I came to London and I had flu for the first week, so I just read a biography of Syd Barrett that someone had given me and I realised that the flat I was renting was really just three seconds away from the apartment that you see on the sleeve of Barrett’s first album The Madcap Laughs. So I got out of bed, in spite of the fever, and went to visit it. I just hung around outside the place for a while trying to pick up something, some vibrations, and it was there that I ran into Duggie Fields, this post-modernist painter.

He was in a tea shop nearby. You can’t really miss him as he has a very eccentric way of dressing, in the best possible way. It was fantastic to meet him, to meet Syd Barrett’s flat mate. We became friends and he invited me to visit the place. He could tell it was important to me, so he let me visit this room in which Syd Barrett had fallen apart but in which he’d also written a lot of songs. It inspired me and I wrote ‘Chambre 29’ and several other songs as a result.

And Duggie appears on Blitz?

ED: Yes, he plays the role of God actually. It’s his voice that opens the album – “There is this door in the desert, you’ll find here another paradise, another world” – and he actually came and gave the speech when I played L’Olympia.

Norman’s Coach And Horses

ED: It’s a beautiful old pub just at the entrance to Soho. I was out with friends, we’d gone to The French House first. And we drank, drank a lot, and started singing. It’s a bar where there’s a pianist who plays a repertoire that goes from The Bee Gees to The Sex Pistols to old English songs, and everyone’s singing at the top of their lungs. It was so beautiful I recorded it. I find that sense of togetherness really moving, when you hear English people singing together in bars.

Do you think it’s particular to the English?

ED: Yes! So I recorded it and held on to it, and at a certain point I knew it had to be used for the song ‘Après le Blitz’. You can hear singing and shouting, so it was as though you’re on a dancefloor but the sky’s about to fall in. “Nous chantons sous les bombes” (we’re singing while the bombs fall) as the song says, that sums up the whole album really.

Etienne Daho outside Sounds Of The Universe, by Richard Dumas

Francis Bacon And The Colony Room

ED: It’s the fantasy of Soho in the 50s, a Soho that’s completely disappeared. There are still places you can go, The French House being one example, that have remained virtually the same – I used a beautiful black and white photo taken there for the cover of a live album (Diskönoir). I need to summon up ghosts to write, and there it was the ghost of Bacon. In fact he lived just near here (in South Kensington). It’s handy because all my muses live not far from me, Bacon had his workshop in Reece Mews just nearby. I felt the need to go there every day when I felt I was short on inspiration. It would be enough to stand there for five minutes or so, or to go into Soho.

The Colony Room has closed sadly, it’s been turned into apartments. It’s sad really, that all these places have been sold and that this history is dissolving. So if you go there now it’s to walk with ghosts, and you can if you’re writing a song, if you’re in that frame of mind – it’s the art of transformation, transforming what you feel. You try to materialise things, but it also means that things and events are attracted to you, it’s very strange. Not just through your own will, it’s as though things and events want to happen to you.

How did it start for you with Bacon?

ED: I’ve always been a fan of Bacon’s paintings, and Serge Gainsbourg gave me a book featuring all of his work. Following that I saw a film, Love Is The Devil, and that reconnected me with his world and in particular his affair with George Dyer, the relationship between an artist and his muse, the way in which an artist consumes and destroys his muse. There’s a brutality there that intrigues me.

You appear to be saying that your muses are already ghosts?

ED: In this case yes. But not always, some are also people who are still alive – despite having met me!

(The) Deep End

ED: In Soho there’s a passage where a scene in the film Deep End was shot, with the photo cutout. Just across from there is a sex shop where Marianne Faithfull filmed Irina Palm, her character gives hand jobs that are so great that the place becomes really popular.

How the song ‘The Deep End’ came about was that I heard I track on the radio by Unloved. And I found out that David Holmes was DJing in Shoreditch, at Rough Trade East, but I got there too late because there was a problem with the tube, then I couldn’t get a taxi. So I said to myself that at least I’d tried. I was just about to head off when I bumped into a guy and it was David Holmes. So I told him how much of a fan I was of their album. Do you know it?

Like many people I think, I became aware of them through Killing Eve.

ED: There’s a song of mine on the soundtrack to that as well, ‘Voodoo Voodoo’ in the fifth episode.

So you’ve carried on working together?

ED: Yes, particularly with Keefus Ciancia and Jade Vincent. They came to see me in St Malo last year and they liked it so much that they left Los Angeles and moved there. But after that meeting with David Holmes we saw each other regularly and Jade sent me this song, ‘The Deep End’, not knowing that Deep End is my favourite film. So we collaborated on my album and on a track of theirs called ‘Remember’.

Deep End was filmed in London by a non-British director, Jerzy Skolimowski.

ED: He worked in London quite a lot actually, Moonlighting is about Polish immigrants working illegally in London, it’s still highly relevant. In Deep End it’s London, the swimming pool… the sound that you have in swimming pools, that sort of reverb and echo that puts you in a very unusual state. The sound is swimming pools is really something quite strange.

It’s also the purity of the character, Mike. When you’re quite idealistic like that you are Mike. The film was almost impossible to find for years, then there was a screening in Paris and Skolimowski, Jane Asher and John Moulder Brown were present. I was invited, as people knew it was my favourite film but I didn’t speak to Skolimowski as there were too many things I wanted to say to him. But as I was leaving I ran into John Moulder Brown, so I told him that he’d changed my life and I took a photo with him. He probably found me rather intense!

His character’s idealism does lead to someone’s death.

ED: But idealism and passion are inescapably linked to death!

The street

ED: In London the fact that the buildings are so low means that you can see the sky. In Paris you don’t see the sky. Apart from on Avenue de l’Opera, which is the only one that’s like a runway, and it ends with a building dedicated to music. But I’ve walked around here South Kensington a lot, you’ve got places like Janet’s Bar, where you find a very interesting mix of people and it’s really great to take photos inside, and the area round Royal Albert Hall. It’s a city for walking and taking photos. The anonymity I have here means that I can go around freely, I take the tube, take photos and make notes. I need to take things from real life, I don’t have enough imagination for fiction. In London I’m like a tourist so I have a picture postcard view of it. But Paris is like that for me too as I’m provincial. Perhaps it’s the fact that I moved to Algeria at the age of seven. You can re-establish yourself anywhere. We are our own suitcases, with everything we need inside.

Thanks to Lucie Travaillé for assistance with the interview. The album Blitz is available via Virgin and he plays his first UK date in four years at Brixton Electric on Saturday January 19