These days Eric Leeds lives a less hectic lifestyle to the one he was accustomed to as saxophonist with every classic band Prince had between 1985 and ’90. Brother of Alan, Prince’s then tour manager, Eric’s first appearance with the mega-star in late ’84 instantly catapulted him into the big time when he was invited to guest on a lengthy jam around ‘Baby I’m a Star’ in front of 15,000 people, only a handful of shows into a 98-date tour to promote Purple Rain.

When Leeds was later appointed to play with Prince official, he wasn’t just hired to fire out riffs, he became one of the key soloists in his band, and his unmistakable jazz-meets-JBs influence would play a dominant role in Prince’s music for the remainder of the decade. Contributing considerably to albums like Parade (1986), Sign ‘O The Times (’87), and Lovesexy (’88), Leeds also lent sax to some of Prince’s later albums and a string of unreleased recordings, all of this while holding down jobs as head horn on three global tours with Prince, and saxist in purple-tinted troupe, The Family.

Sometime between the release of the former and latter of the aforementioned LPs, supposedly as a thank you for his loyalty to his music, Prince gifted Leeds with the reins to his own jazz-influenced instrumental project: Madhouse, resulting in the release of two albums, 8 and 16 on Paisley Park records in 1987. As with other discs dropped by acts associated with Prince in the 1980s (Sheila E, The Family, The Time, Vanity 6), Madhouse was pitched as a ‘band’ project to fans and the press, but in time was revealed as a smoke-screen for what was essentially another Prince production, with the multi-instrumentalist manning the desk and playing all the instruments – in this case bass, drums and keyboards – behind some funky tenor and flute from Leeds.

While jazz purists might recoil at the thought of a Prince-produced jazz record that came in a sleeve bedecked by a busty brunette and that featured numerically named tunes linked together with seductive French dialogue, moans from a girl at the peak of sexual excitation and some samples from The Godfather, both albums are worth seeking out, purely for Prince’s illicit groove playing and the seductive lines Leeds lays over the beats.

Much of Madhouse was borne out of regular jams with the Revolution, and aborted studio projects such as the much-discussed Flesh sessions from ’86, but select cuts from the albums made it on their own merits (‘6’ from 8 made it to number 5 on the black singles chart in ’87). The records have since remained greatly-admired amongst Prince fetishists and musos alike (a clip on YouTube reveals how drummer Questlove got the gig with D’angelo after the singer heard him execute the familiar funk drum intro to ‘4’ during a Roots show he attended) which is most likely why Leeds agreed to dissect and discuss the sessions once more, and in the process disclose some insightful stories on his super-talented ex-boss.

How did the sessions for the initial Madhouse album come about, and what was the inspiration behind the music?

Eric Leeds: The first Madhouse album was recorded in fall of 1986 in three to four days the inspiration was solely Prince’s. Having come off a string of dates with his newly expanded band, which I liked to dub the "Counter Revolution" I guess he just felt like doing something different. Jams with Prince and various members of the band were common, so perhaps he wanted to do something more formal in an instrumental vein.

Is it true that the Madhouse sessions were a sort of thank you from Prince for your loyalty to him and his music?

EL: I was very fortunate and grateful for the role that Prince provided for me in his band as the primary instrumental soloist, other than his own guitar solos. Perhaps he was interested in giving me an expanded platform. But he was someone who always had music in him that he needed to get out, so even if I had not been involved with him I suppose he might have done a project like this anyway. This was a period during which he was still defining himself, and that included a keen interest in instrumental music. He listened to Miles (Davis), Weather Report, Return to Forever…

Where was the music recorded, and can you describe the mood of the sessions and how the music was put together and laid down?

EL: The first album was recorded in his home studio in Chanhassen, Minneapolis, where we did a lot of recording. Paisley Park Studios had not been completed, and in fact the recording console in his home was moved to Studio B at Paisley Park when it opened the following year. The sessions were little different from any other session that I had done with Prince, though this project was just the two of us (and Susan Rogers who engineered the project). Prince laid down the tracks (drums, bass and keyboards; there was no guitar on the first album) and he would give me the melody lines such as they were, and we would go from there. Prince wrote all the music on the first album.

It’s well documented that you introduced Prince to a lot of jazz music, what sort or records did you play to him, and what was his reaction to them?

EL: Well, I introduced him to some jazz. He had a rather broad, but not deep, exposure to jazz. I remember giving him A Love Supreme and Ellington At Newport which he loved. Also several of Miles Davis’s second great quintet LPs such as Miles Smiles, ESP, Sorcerer, and Nefertiti. He was familiar with things like Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson, but less so with others. He was familiar with A Kind Of Blue and probably Sketches Of Spain, and also the aforementioned Weather Report. I suppose he related more easily to the more funk-oriented things. I don’t recall how much he might have listened to the other things. Prince also enjoyed listening to various classical recordings but I couldn’t comment on exactly what.

Miles Davis dubbed Prince a modern-day Ellington, Would you agree, and how would you describe Prince’s approach to playing jazz music?

EL: I suppose Miles was commenting on Prince’s eclecticism and that he was a masterful pop songwriter much as Ellington was in his day, at a time when jazz was pop music. Prince’s approach to playing jazz was little different from his approach to playing anything else. At times, he had a great sense of spontaneity, particularly in jam sessions and also often in our club "aftershows". But once he started to formalize something, I often felt that his determination to control everything worked against it being allowed to kind of find its own way in a more orthodox jazz sense. Having said that I do have some personal recordings of various unreleased jam sessions that I feel are more exciting than any of the released Madhouse material. In a more formal jazz context, Prince lacked the full harmonic vocabulary that even the most conservative jazz musicians took for granted. Certainly, much of Prince’s recorded work is more harmonically sophisticated than most pop music, but the jazz vocabulary is in another league entirely. Also, while Prince could smoke the hell out of any kind of duple meter groove such as R&B, funk or rock, he had no feel for a triple meter jazz swing rhythm, so that limited the jazz component from my admittedly more orthodox perspective.

Madhouse O)))

As far back as 77 and his first demos for Warners, Prince has a natural approach to playing instrumental music and improvising, what do you think steered his talent for improvisation and structuring music like this?

EL: Regardless of my previous comments, he would often surprise the hell out of me with his guitar vocabulary, and certainly could play tremendous extended solos, as long as the groove was in his "wheelhouse". Everyone is familiar with how he’d play the formal guitar solo at the end of Purple Rain, for example. But sometimes, he’d open the song with a long guitar solo on a straight, almost jazz-like sound and just kill it. Those are the solos of his I always looked forward to. Prince came of age at a time when pop instrumental music was still common, and given his gift as a guitarist particularly, but also as a pianist and bassist, it was only natural that improvisation and instrumental music would be a prominent part of his musical vocabulary. Aside from his performer’s persona and gift as a pop songwriter, he also just loved to simply play music.

Stylistically, there was a clear ‘Minneapolis sound’ underpinning the tracks but how much freedom did you and other musicians have to improvise and add to the writing?

EL: The Minneapolis Sound was already defined by the time I started working with Prince. I’m told that many of his compatriots in the Twin Cities were surprised when he embraced the use of real horns in his music, since he had always been reluctant to use such a traditional texture. But the fact that myself and close friend Matt "Atlanta Bliss" Blistan who played trumpet played instruments that Prince could not play gave us much more input as to our role in the music, at least at first. I had an opportunity to contribute several of the horn arrangements, though other times the horns would just compliment what was already going on with the keyboards, etc. As for my solos, they were always improvised at first, but once I had a good idea of what worked best in any given situation I would use that as a basis for the solos as I would play them in performance. The goal was to make the solo as essential a part of the song I could. Sometimes, Prince would have a specific idea in mind as to how I should approach a solo, and that was fun for me, because it often meant that I would have to think about it differently than if left up to my own devices. As time went by, Prince became more comfortable with using the horns and wrote more of the arrangements himself, usually communicating to us what he wanted by singing the parts or playing them on guitar or piano.

Hearing more full-band improvised moments like ‘Junk Music’ for example, there is more spontaneity and music tension amongst the players. How much licence for creativity was there playing in a band under Prince’s direction?

EL: ‘Junk Music’ was a 45-minute jam recorded in the studio. Prince was on drums with Sheila E. on percussion, myself, Wendy Melvoin on guitar, Lisa Coleman on piano and Levi Seacer Jr. on bass. Prince simply called a key, counted it off and we hit it. I edited it down to about 20 minutes for a possible album project that Prince simply called The Flesh. A few minutes of it appear as incidental music in the film Under The Cherry Moon. Obviously The Flesh was never; excuse me, completely fleshed out. It was a good example of what might happen when we had no particular agenda other than simply to play off of each other in a completely spontaneous, unscripted context. Wendy and Lisa had a rather distinctive harmonic pallet that is shown to good effect here. While neither of them were soloists in a jazz sense, they had "big ears" and were very sensitive in supporting and forming a direction for what was happening. I really enjoyed what they brought not only to Prince’s more formalized music, but also to situations like this. This was where we would have the most license as far as creating our role in the music. In the context of his concert band Prince would pretty much create a musical character for each member. As I mentioned earlier, the horn section (Leeds and Blistan) had more freedom to define our roles inasmuch as we played the only instruments in his band that Prince could not play!

Was there any inspired improvised moments that didn’t make it onto the final cuts?

EL: It’s my recollection that everything we recorded for the first album was included on it.

The first record 8 was recorded between yourself and Prince in a matter of days, but do you think the tunes would have had more substance had they been performed in a live setting by a full band?

EL: Short answer is yes, I do. The second Madhouse album 16 was comprised mostly of jams played by Prince, myself, Sheila and Levi. I thought that album was much more successful musically with better realized compositions and better performances. That it wasn’t as successful as the first in the marketplace is perhaps due to the loss of the curiosity factor and also an ill-timed release date.

You were once quoted as saying that you never thought much of the record and that it was "more play-acting" than a real jazz album. Could you elaborate on that?

EL: Prince didn’t really approach this any differently than any other recording. He would construct the songs in his head, lay down the drums, bass and keyboard tracks, and then bring me in to put on the heads and solos. This is hardly how a conventional jazz album would be recorded. I guess I would describe it as "jazz influenced" and R&B-flavoured instrumental music. I don’t offer that as a judgement on the value of the music, merely as a description. That I didn’t care much for it is merely an opinion on the specific music involved in this album, not on the concept itself. Who knows, on another day with a different group of songs I might have ended up digging the hell out of it.

Were you surprised when cuts from the album made it into the black singles charts?

EL: Yeah the song ‘6’ was a top ten R&B radio hit. Of course since the beginning of the rock/R&B era, instrumental music was very successful. Artists like King Curtis and music recorded by James Brown’s band for example yielded huge hits. But by the 80’s instrumental music on pop radio was very rare. So when ‘6’ took off it was somewhat happily surprising. Of course a very creative PR campaign helped develop a huge curiosity factor. This was still a time when anything remotely associated with Prince drew huge attention.

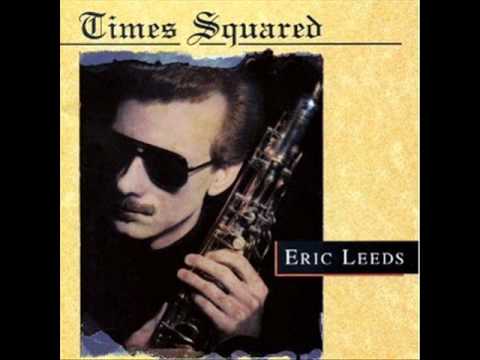

As with records by The Family and later your own Times Squared record (from ’91), the Madhouse albums were released during a very creative peak in Prince’s career. Do you think the project had legs and deserved more of a promotional push?

EL: The first album was successful in part to the promotional campaign that we created for it. By the time the second album was released, the curiosity factor had declined, and instrumental pop music was an endangered species. It was also clear that by the time the second album was released Warner Bros. had become more circumspect in which of Prince’s projects they were really interesting in supporting.

What are your thoughts on the music on those albums today?

EL: I’ve never cared much for the first album. I thought it had some interesting moments, none of which really jelled into anything particularly interesting to me. The one exception, for me, was the title track ‘8’. I thought that one was much better developed than anything else on the album. And from my own admittedly limited perspective it was the only piece on the album that I actually liked what I played! I liked the second album quite a bit, with the exception of two tracks that I thought were pretty lame. But most of it was played by a rhythm section in real time, and I just liked the songs better than the first. Sheila is the drummer on most of it, so that speaks for itself. But Prince is playing drums on the title track ’16’ and he kills it.

What happened with what should have been the third Madhouse album 24?

EL: There were several iterations of what would have been the third Madhouse album. In December of 1988 we completed the third album. Once again it was just Prince and I, and once again Prince wrote and recorded all the music, then brought me in to add my parts. I was also once again very ambivalent about the album. Some things were cool, but overall I was less than excited. After several months it also became clear that Prince had lost interest in it. Interestingly, Prince sent a couple of the songs to Miles Davis who ended up performing them with his band! It’s also possible that Miles rerecorded them with his own band, but I’m not sure.

The following year I started working on a second version of a third Madhouse album. That was eventually released under my name as Times Squared. The only thing on it from the original third album was an edited version of a piece called ‘The Dopamine Rush’. Several of the songs on Times Squared also originated from the sessions that yielded ’16’. On a couple of occasions over the next two or three years, Prince and I, and members of the NPG, went into the studio and recorded what would have been another attempt at a third Madhouse album. Other than one song titled ’17’, that I believed was released on an NPG sampler, nothing from those sessions has ever seen the light of day. The musical health authorities finally closed down the Madhouse and released all the inmates!

Finally, what are you working on at the moment?

EL: We (Paul Peterson, Susannah Melvoin, Jellybean Johnson and myself i.e. The Family) resumed our musical relationship several years ago and renamed ourselves fDeluxe and have recorded three albums "Gaslight", "Live and Tight" and "AM Static". All are available on our website fDeluxe.com. We performed a few years ago in London at the Jazz Cafe. My primary project currently is LP Music. It’s an instrumental project put together by myself and Paul Peterson and features a revolving cast of characters. Paul’s brother Ricky Peterson often performs with us on keyboards as does Stokley Williams on drums who is perhaps better known as the lead singer with the group Mint Condition. I’m also doing some teaching and will soon be developing a website through which I’ll be able to have interested students take lessons online from anywhere in the world.

My role in Madhouse was created by Prince, and though I have my own opinions on some of the music, I always felt very fortunate that Prince thought highly enough of my playing to have given me that opportunity. The visibility it provided me and the cachet that the band had, particularly among many young musicians, led to my forming some great relationships with many wonderful musicians. I will always be grateful for that.

You can check out LP Music at leedspetersonmusic.com

Thanks to writer Matt Thorne for the link to Leeds and to long-time Prince devote Lee Bromham for extra info relating to this article