I was not quite ten years old when Joy Division released ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, a song I immediately loved to the slight concern of my parents. Three years later I became obsessed with New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’ and heard The Smiths for the very first time. Being born and bred in Manchester, I thought this was par for the course. I assumed everyone’s town contained great bands and it was a matter of just plugging into whatever cool tunes were in the local vicinity. It never occurred to me that for the vast majority, this wasn’t the case. I was an idiot, clearly.

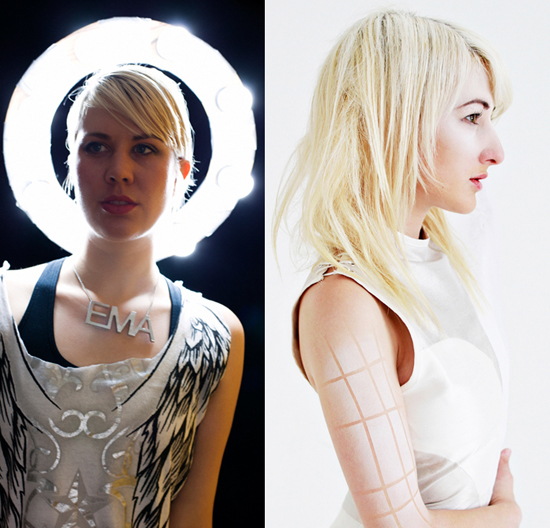

The memory of this uneasy realisation floods back as I sit in the soulless dressing room at the Manchester Academy with Erika M Anderson and Nika Danilova – or EMA and Zola Jesus, respectively. They have at least two things in common – both have released sparkling albums during 2011 (EMA with Past Life Martyred Saints and Zola Jesus with Conatus), and both are from small towns in America’s vast Mid-West. Sioux Falls in South Dakota and Merrill in Wisconsin are separated by 350 miles of prairieland and a whole lot of weather.

A couple of weeks before speaking to Erika and Nika, I interviewed the band Real Estate for The Quietus. They hail from an affluent suburb of New York and tell me that during their formative years they were exposed to a huge range of resources and support to fuel their interests in making music. One of the reasons they formed Real Estate was to not squander the opportunities bestowed on them. I’m guessing – and I may well be wrong – that Erika and Nika were not quite as blessed.

So, I’m eager to explore how their places of upbringing influenced their art. Thankfully, even though they both seem knackered after a long year on the tour treadmill, they seem happy to indulge me, even if they are “sick of journalists talking about South Dakota and hunting”. Bravely, I soldier on.

Okay, so this is the pitch. I know you both spent much of your childhood in relatively isolated Mid-West towns. I was thinking about your music and wondering how much it has been shaped by the places in which you both grew up.

Erika Anderson: I’ve been thinking about stuff like this. As far as being from a small place there are some things that are really great about it, but I’ve definitely spent a lot of time being jealous of people who went to a bunch of music classes and had a lot of exposure to things – and maybe learned to speak different languages. I feel there is a lot of potential there that I didn’t have a chance to work on. But on the flip side of that, one thing I do have from those high school years, even if I don’t have any sort of formal musical knowledge or connections, is I have a lot of stories – a lot of fucking weird stories that maybe are unique.

So let’s backtrack, which towns are you from?

EA: I’m actually from a city – it’s called Sioux Falls. It’s just not very cultured.

Nika Danilova: It’s not worldly.

EA: Ha. It’s not very worldly at all.

ND: I was born in Phoenix and lived there for two years and then my parents moved me to Merrill, Wisconsin, which is a city of ten thousand people. I tried to send myself away to boarding school a couple of times.

EA: I tried to do that too.

ND: I’d fill out an application form a couple and slip it under my parent’s bedroom door. They said no.

Both those places endure bitterly cold winters and are geographically isolated, in the sense of being part of a huge expanse of prairieland. Does climate and topography play a part in creating how you think as artists?

EA: Yes, a lot of the memories I have are of extreme weather and space. I believe in the effect geography can have on the music you make, in as far as your idea of space and your idea of sounds. I had this experience of being in this really amazing weather, where it was very dramatic and it made me appreciate drones and static, just because it felt like that.

ND: I know what you mean. There is such a solitude about living in those expansive places that you can be in a place of almost complete silence, but within that you take in the sounds and nature. Maybe you appreciate that more than someone who grew up in the city and was afraid to go into the woods.

Is it true that both your fathers are hunters?

EA: Yeah, we were talking about that before. My dad works to conserve land and put areas into trust to stop them getting polluted. You will find that a lot of hunters are the biggest conservationalists.

ND: There is an over-population of deer where I come from.

EA: I heard in Wisconsin that most car crashes are from people hitting deer.

ND: It’s terrible. The deer take over. You gotta defend yourself against them. And bears.

EA: True and you don’t hear complaints when New Yorkers kill cockroaches.

If I can drag this back onto topic, what was your initial exposure to music and what opportunities did you have to explore?

ND: My dad had a pretty good taste in music. He would always be listening to Talking Heads, Oingo Boingo or New Wave. So, I grew up with that stuff, not really knowing what it was but that it was in the periphery. Obviously there was a radio, and I would switch between NPR and Jam stations, because that’s all there was. But even the popular music was six months to a year behind what was going in anywhere else.

Really? A year? I’m surprised – we are not talking that long ago.

ND: Yeah, in order to get airplay where I live it needed to be already so popular, because no one can take risks in such a small town. Everything is very base level. There is no experimentation or taking a leap on anything.

EA: I would also say that still my friends in South Dakota have the best taste of everyone that I know, because whatever makes it there – whatever starts on the coast and makes it inwards – is three years late but they only listen to really good shit. They don’t fuck around. If it’s not good, it’s not going to penetrate.

ND: It’s gotta make it through.

EA: It’s like a water purification system. By the time we get it, it’s pure.

Can you remember the moment when you ‘found’ a band or album that felt like yours, as opposed to something you heard via your parents or older siblings?

EA: Yes, absolutely. I remember being about 12 or 13, something like that, and going to a used CD store and for whatever reason buying a Bikini Kill CD and a Babes In Toyland CD on the same day. I don’t know how I’d even heard of these names.

ND: Mine is kinda similar. There were different waves. The first instance was Riot grrrl and that was like the gateway drug, a little bit. That was the thing I had as my own – Bratmobile, Bikini Kill and Babes In Toyland. Then it went on and I started getting into even stranger bands like The Residents and then experimental industrial stuff.

Were you part of a particular ‘scene’ at that time?

EA: Actually, in my town there was a kind of really freaky scene in some ways. There was an emo-hardcore scene that was going on and there were other people that were just really fucking weird.

ND: It’s hard to say because I never had any friends in high school or growing up.

EA: Is that for real?

ND: Yeah, I had no friends. So, I never really had any connection, even musically, with anyone. I’ve never been in a band with anyone and the emo-hardcore thing was the only thing that ever penetrated.

I’m from a big city and one of the advantages is that scenes become very fragmented and niche and you can find the space that best suits you. My sense is that in small towns you are either one thing or the other, with very little in between. Was that true in your experience?

EA: Well, in my town you were either with the system or against it. At high school at one point I had combat boots and a shaved head. People would be like ‘you fucking hippy’. I was in the ‘other’ and the other encompassed everything. You could be into ska or punk but you could be a tree-hugger to them.

ND: Any sub-culture got lumped together.

What are the advantages of being a musician in a small town?

EA: There are obviously benefits from being from a large place where you get exposed to a wide variety of things, but one of the benefits of being from an isolated place is that no one is watching. You can do whatever you want and there is a freedom in that because no one is going to notice anyway. I can do what I want to do. What happened, for me at least, is it became very intrinsically motivated. I’m motivated by myself to make what I want to make – there is no dream of stardom.

ND: Yeah, you are not learning the tricks from someone else to fit into a certain scene. It’s like, ‘I don’t have a drum set, so I am going to make up a beat.’

Erika, when we last met, you talked about people in Sioux Falls being both nihilistic and poetic – would you care to elaborate?

EA: Well, in my town there is no formal art. There are no actors or writers or painters. There is nothing to do really. People just intuitively go for these big, dramatic gestures. One of the things I think about a lot is being drunk with a friend of mine outside the worst bar in East River right across the street from the police station. She started taking bottles from the back of a cart and throwing them into air, just to watch them fall and smash. She started with empty ones but went on to full beer bottles. It was perfect – it was beautiful. It’s almost like performance art, like Chris Burdin or some Dutch artists I’ve seen. So, maybe I didn’t have a formal education, but I feel like I had a freedom to appreciate beauty and make grand gestures that express the fucking arbitrariness of life.

ND: It becomes a release. You find your release in different ways, maybe through art or music. It’s that finger [makes the gesture] and it became music for me, eventually – even if the finger is towards myself. It’s like a catharsis to express something or explain something that’s within in all of us. Maybe that’s an anxiety of nihilism.

Finally, if you had been brought in a Los Angeles or Brooklyn, would EMA and Zola Jesus sound like they do? Would they even exist?

ND: A lot of what I make is an expression of where I come from because there is a sense of survivalism, which I definitely picked up along the way, because I didn’t have those contacts. I just had the freedom to be loud; you can only be heard if you are loud. If I had a bunch of formal training and lived in a place with a lot of opportunities, I might make proper music and I might understand things a little bit better but I don’t know if it would be as intense for me – it might become a little bit placid.

EA: Someone asked me recently in an interview, ‘Do you feel like you are an indie-hipster darling now you are getting all this attention? And how does that feel?’ What’s interesting is that growing up where I did I am one of the people that has real experience of both sides. I have experience of the place where people hate anything with the merest whiff of pretension. They are really suspicious. But then I have also lived in Los Angeles where I’ve done these experimental shows of electronic music, which some people might think was hip. But growing up in a small place gives you a wide level of empathy for different sorts of people and I think that’s really important. I think people from large cities should have to go and spend six months in Kansas, just so they can have empathy and figure out what these Red States are about.

ND: When you live in a bigger city, people are a lot more compartmentalised. There are many different groups, whether it be racial or by what music you like or what you wear or who your parents are. Growing up in the middle of nowhere, everyone is the same. I want to make music that reaches the human and not the clothes on top of them. Artificial interest songs are superficial – it’s about connecting.

Past Life Martyred Saints by EMA and Conatus by Zola Jesus are both out now