For the past two summers Elvis Costello has toured the UK showcasing his back pages via a multi-coloured giant wheel. Billed as The Spectacular Spinning Songbook, it’s a novel way to determine what will be played each night. Audience members are plucked from the stalls and invited to give the wheel a spin.

It might stop on a stone cold classic of yore (‘I Can’t Stand Up For Falling Down’, ‘Alison’, ‘Accidents Will Happen’), an oft-overlooked album track (‘Country Darkness’, ‘Strict Time’), or an umbrella subject bar like "crime and punishment", "girls" or "Joanna", that final category the cue for a short sequence of songs with Elvis accompanied only by long time piano player Steve Nieve while the rest of The Imposters take a breather.

Like any artist with more than 20 albums under their belt, Costello has a hell of a lot of songs to choose from, although punter expectation dictates there are big hits he can’t realistically ignore. In practice, about half of each night’s set is nailed down in advance, regardless of the whims of the wheel, but the thrill and anticipation for most fans lies in the randomness of the other half.

Those fans will have a field day with Wise Up Ghost, Costello’s forthcoming collaboration with neo-soul/hip hop maestros The Roots, and his first album for three years, because while the track listing reveals a dozen new titles the fingerprints of his past are liberally smudged throughout. All but the most obsessive Elvis fans might want to skip the next paragraph, but here’s a partial run-down of the self-referencing pit stops…

The moody, ominous title track contains lines from ‘She’s Pulling Out The Pin’, the 2004 album cut that crops up again in ‘She Might Be A Grenade’; ‘Refuse To Be Saved’ begins with a quote from 1991’s ‘Invasion Hit Parade’; ‘Tripwire’ is based on a sample from the Bacharach-like melody of 1989’s ‘Satellite’; ‘Wake Me Up’ solders the verses of 2004’s ‘Bedlam’ to the chorus of 2006’s ‘The River In Reverse’. The most blatant scrap-booking, however, can be found on ‘Stick Out Your Tongue’, in which Costello revisits the angry protest of the 1983 Top 20 hit ‘Pills And Soap’ (released in the run-up to that year’s UK general election under the name The Imposter), adding fresh verses of venom to his scornful portrait of the powers that be ("Her Majesty will run on Bombay gin and German spite").

All this reupholstering is set to a musical backdrop suffused with taut grooves and break beats – not exactly a hip hop album, but the closest Elvis is ever likely to come to making one. Co-produced by the man himself with The Roots’ Ahmir ‘?uestlove’ Thompson and Steven Mandel, the prominent tone is the sublime soul rhythms of, say, The Meters or Curtis Mayfield (‘Sugar Won’t Work’, ‘Walk Us Uptown’), with occasional detours into urban-tinged psychedelia (‘Viceroy’s Row’) and ballads of cautious optimism (‘If I Could Believe’).

The multifarious lyrical allusions to what went before reinforce the recurring theme of the album, a series of snapshots illustrating how humanity is still in deep shit; the songs may not remain the same but the state of the world hasn’t changed much.

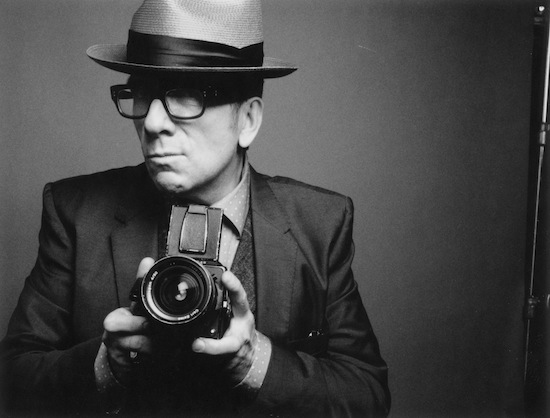

Costello greets The Quietus in a Kensington hotel, his frame as lean and wiry as the 23-year-old caught scowling on the front sleeve photo of his 1977 debut My Aim Is True. He admits to being tired, only just past the halfway mark in a three-month trawl of European live shows, but his energy levels rise noticeably as he warms to talking about the new record, and the enduring power of some of his former glories.

You’re no stranger to the collaborative album, but saddling up with The Roots seems, on paper at least, to have particularly come out of the left-field. Where and when did it begin?

Elvis Costello: Aside from making records as The Roots, ?uestlove is involved in so many other things as a drummer, producer, DJ, author, he’s ridiculously busy. On top of all that, they’re the house band on Jimmy Fallon’s TV chat show in the US, but they do it with a bit of imagination, they cover a huge range of music. They don’t just sit there and play in the background, they add their own subversive touch to it. I’ve had the opportunity to play with them on the show on three occasions; the first time we did ‘High Fidelity’ in an arrangement I hadn’t played myself since about 1978, it was originally a very slow song, and they based their version on an old bootleg they’d found. It’s that idea of inspired reinventions that has always appealed to me.

They make hip hop that’s in a lineage of classic intelligent music…

EC: I don’t think there’s a huge amount of difference between their intelligent approach to hip hop and the kind of thing Jerry Dammers was doing. He was using figures and melodies from Prince Buster, then writing new words over them. I know some people have a bit of a prejudice against that idea of reworking things, but it isn’t so shocking to me, it’s not as if everything played by a band was original in the first place, that’s nonsense. Everybody’s taking from the best and adding a part of themselves to it, but it’s a question of the flair with which you do it – the audacity with which you steal and what you make out of the component parts, whether it’s a Howlin’ Wolf riff or whatever. I think what they do has a lot of wit.

So, I went in and did these couple of performances with them in their tiny rehearsal space next to the studio, it’s really not much bigger than a large cupboard. It’s a pretty economical set-up, not especially glamorous, but it seems to lend itself to a climate of experimentation. Another time I was on Jimmy’s show it was Bruce Springsteen week, where every musical guest was obliged to perform Bruce’s songs, and The Roots came up with a new arrangement of ‘Brilliant Disguise’ for me. I’d recorded the song previously as a straight country number, but they’d stripped it down to this thing that was just piano and drums. Then we did ‘Fire’, which Bruce had given to The Pointer Sisters as a straight-forward pop song, but we did it like ‘The Liqidator’, the old Harry J & The All Stars reggae hit.

Were you always on the same page, in terms of references?

EC: This is where the mixing of styles comes into its own; ?uestlove was convinced the riff came from The Staple Singers’ ‘I’ll Take You There’, because that was his introduction to it, but in fact it originated from ‘The Liquidator’, which us British musicians had first heard in the youth clubs of our teenage years, that pre-Rasta reggae of the Tighten Up compilation that everybody seemed to have bought, which had its roots in Motown. You didn’t have to be a hipster to be familiar with that stuff, because the likes of Harry J or Dave & Ansil Collins were the bread-and-butter of every school dance, along with Motown Chartbusters Volume 3. None of us were particularly scholarly back then, we just absorbed the hit music of the day. I can’t pretend that I knew all the rare stuff until I went to America some years later.

But I’ve never felt the labels people put on music are important, whether it’s soul or country or jazz, it’s more about what the music makes you feel. That’s what I really appreciate about ?uestlove, he doesn’t set himself any boundaries. He’s got a tremendous knowledge about all kinds of music, I mean he knows a lot of my stuff that passed other people by.

Speaking of your "stuff", the reference points to your back catalogue on Wise Up Ghost are many, particularly in the re-appropriating of lyrics from earlier songs. What was the thinking behind that?

EC: After we did the Bruce songs on the Fallon show ?uest came up to me and spoke in very elliptical terms about doing something more enduring together. There was a thought about just doing a catalogue record, ie a collection of my old songs but re-imagined by The Roots. The first song they proposed doing was ‘Pills And Soap’, but I didn’t really see that as a strong idea because it’s already what it is; it was a bulletin of the times in which it was recorded, so I wasn’t keen on doing a literal remake. I suggested we pull it apart, so I started improvising a whole new structure that retained some of the melodic skeleton, some of the words, but it was much groovier with more vocal hooks, also quoting some of the lyrics to ‘National Ransom’ [the title track of Costello’s last album, from 2010].

It’s interesting you use the word "bulletin", because there are several points on Wise Up Ghost where it feels like the listener is channel-hopping through a series of disparate news stories and incidents that weave together into a whole.

EC: Well, to my mind the song writing I’ve been engaged in over the last few years hasn’t seen a great distinction between the circumstances now and the circumstances of when I wrote ‘Pills And Soap’ or ‘Shipbuilding’ or ‘Tramp The Dirt Down’. The premise of several of the songs on National Ransom was that things are not really any different to what was happening 30 years ago, the common ground is the same; the same lies are being told, they’re just dressed up in different PR clothes. In terms of how we allow ourselves to be governed, I don’t think we’ve learned much in god knows how many decades, I honestly think we can do better. I’ve never been in the happy-clappy "let’s make a better word" business, but you can’t help noticing how little things have changed.

So, we started by dismantling ‘Pills And Soap’ and reconstructing it into something else called ‘Stick Out Your Tongue’, which to my ears has humour where the first record was pretty bleak. I mean, if you’re gonna be taken in by the same lies 30 years later you’re gonna have to have a sense of humour about it. I took that one line "stick out your tongue" from ‘National Ransom’ as if to say "the hell with it", to try and face it down, rather than offer any kind of tangible protest.

From there on the rest of the album just rolled out, we didn’t sit down and have any kind of conference about what we wanted to do. ‘Stick Out Your Tongue’ had the notion of updating ‘Pills And Soap’, but nothing else was done with the thought of adhering to an agenda or any kind of plan. I think most of the other instances where verses from records of the past have been re-set the original songs are so unknown to the broader public that they’ve become entirely new pieces, rather than remakes or sequels. Obviously, if you collect stamps or spot trains you’re gonna be ticking boxes and saying, "Oh, I recognise that from blah blah blah", but who the fuck cares? My record sales attest to how few people heard them first time round! I’m not saying anything against people who do spot things from my older material, thank god somebody was listening to them, but the point is that what the song is saying now is still happening.

Is the suggestion that, if the new album does have any sort of linking theme it’s one of rum business as usual?

EC: I suppose so, but it’s always been about the black comedy of the way things are. This is not said with any disrespect to individuals or families, but the Our Brave Boys culture I’d previously touched upon in ‘Oliver’s Army’ and ‘Shipbuilding’ has contained within it a certain pact that we’re obliged to endorse the policies that put our brave boys in harm’s way in the first place. I’d much rather they weren’t the fuck there, of course, and a lot of the things the songs end up talking about don’t necessarily come with any solutions. They’re commentaries, set to musical collages, but don’t go looking for any quick fixes because you won’t find any.

Initially, you hadn’t given much thought to making an album at all, though.

EC: No, we hadn’t planned on it when we first started recording. After the first couple of things were done we started arriving at a structure where songs like ‘Walk Us Uptown’ or ‘Cinco Minutos Con Vos’ were completely new without referencing my back catalogue, and the idea of an entire album just presented itself. We’d made no arrangements with the record company to deliver any product, we didn’t mention the fact we were working together to anybody except a few close friends. The first time the record company knew about it was when it was just about finished and we asked them if they’d like to put it out.

You were quoted in an interview with The Word magazine about five years ago saying you thought it was unlikely you’d ever make another album. Since then, Wise Up Ghost will be the fourth you’ve released.

EC: I’ve said that a few times over the length of my career, actually! I think it’s always important to have the feeling of freedom that you’re not bound by the requirements to make records when you don’t want to. It’s a tremendous privilege to stand on a stage and sing, no matter how good or bad you might be, and it’s a tremendously enjoyable thing to make records, but it’s the commercial pact you have to strike afterwards that’s often the pain the arse. Sometimes it can be very dispiriting, and people can take the wrong thing out of what you initially set out to do, or run with a very simplified idea of what you were trying to do.

Do you think you’ve been misunderstood in the past?

EC: It’s bound to be frustrating if people don’t immediately "get" what you’re doing, but in the long run it really doesn’t matter. The long game of this is that records initially dismissed as follies end up being feted as much as 20 or 25 years down the line. It’s happened to me a few times, I’ve had letters of apology from areas of the media that were less than welcoming to albums like Mighty Like A Rose or Painted From Memory – some critics viewed those records as some kind of betrayal on my part. You can’t allow the opinions of a few to stop you in your tracks, though, because ultimately there were more people who embraced those records.

But you have seriously contemplated not making any more…

EC: Well, there was really no plan in my mind to make any more recordings after National Ransom, because quite honestly, and not to be morbid, I know that I don’t have an endless amount of time left, and I was trying to divide it up for the best of my mental and emotional health. The plan was to just pursue my vocation as a performing musician, which I do really well, and that’s how I make my living. I couldn’t honestly justify the time away from my family to make records, even at that high level. National Ransom has The Imposters and [bluegrass A-listers] The Sugarcanes on it, the two best bands I’ve ever worked with, you can’t actually work with any better musicians. On top of that, there’s the best producer in the world [T Bone Burnett] who happens to be my friend, as close as a brother, and it’s difficult to imagine ever trumping that. It was one of the two or three records of mine that I will always value above all others; I like the contents of all the other albums, in terms of the songs, but I can’t say I like the way the records sound, retrospectively.

Are you really not fond of most of your old output?

EC: An album like Punch The Clock that has ‘Pills And Soap’ and ‘Shipbuilding’ is obviously a great record, the strength of the songs outweighs anything you might think about the sound of it, but that’s why it’s important to play live. There are songs on that album that we’ve found our way back to, that we’ve kind of salvaged, by playing them in concert, the same with an album like Brutal Youth. We played ‘London’s Brilliant Parade’ a couple of nights ago, and I’d forgotten how proud I was of that song, it’s such a true portrait of the way I feel about my home town, not that I live here anymore.

Mighty Like A Rose is an album that tends to get short shrift, but on these dates we’ve been playing ‘All Grown Up’ and ‘After The Fall’, and it’s been really beautiful. Not every song can be a world beater, not every song is operating on the same impulse or function, but the live stage allows you to locate elements that might have passed you by in the studio.

The Spectacular Spinning Songbook is an interesting way of approaching your back catalogue, enabling you to dust off the forgotten or unfavoured. It’s a long show, pushing three hours some nights, and you seem to relish throwing in some surprises that aren’t covered by the wheel.

EC: I like the juxtaposition the wheel concept affords me, where I can dig out things I’ve not played for years, but the audience still get their fill of the expected and the well-known, i.e. songs that I almost have to sing, although those songs differ depending where I am. The curious thing in Turkey is that the two songs I’m obliged to sing are ‘She’ [Costello’s last Top 20 hit, a cover of the Charles Aznavour croon recorded for the soundtrack of 1999’s Notting Hill] and ‘I Want You’ [the brittle, brutal study in obsession from 1986’s Blood And Chocolate]. They’re the two songs for which I’m best known over there, despite being polar opposites of romantic love. ‘I Want You’ has to be played in Holland and Belgium as well, more than any other tune I’ve ever done.

It comes down to the period in your career where you had the biggest sales, that’s a given. In England, most people’s knowledge, interest, affection or nostalgia is in those two or three years at the end of the ’70s when we were a big pop thing, and a lot of people switched off after that. Then there are huge swathes of America where we didn’t really surface from the underground until about ’82 or ’83. They have a retrospective knowledge of the songs from, say, This Year’s Model, but for them it’s all about Imperial Bedroom or Punch The Clock.

Leading on from that, did you feel obliged to play ‘Tramp The Dirt Down’ [Costello’s eloquent diatribe against Margaret Thatcher, released in 1989 but written around the time of the UK general election two years earlier] on these last British dates?

EC: No, not really, because I was playing it when I toured here last year and Thatcher was still alive. Obviously, it didn’t have the same weight or anticipation attached to it as this time around, and it got written about a bit when she died in April, although not as much as ‘Ding! Dong! The Witch Is Dead!’. It certainly wasn’t one of the most downloaded songs on iTunes that week. Having said that, it was the most downloaded of my songs that week, but that could mean it had four downloads instead of three the previous week for something like ‘Alison’ or ‘Oliver’s Army’; that’s the false science of statistics. A few people in the media made a note of it, and people were ringing me up for quotes within minutes of her death being announced, but why should my opinion matter? And why would I have anything to add to what I’d already said in the song?

But you have been addressing audiences before playing it.

EC: Most nights when I’ve come to sing the song I’ve prefaced it by the acknowledgement that my father died of Parkinson’s 18 months ago, and the last six months of his life were pretty wretched with dementia. So, on a human level I’m enough of a good Catholic, residually, to not wish that on my worst enemy. If that’s how she died, then it was a pretty wretched way to go, even for somebody who seemed to have such malice in her heart for certain portions of society, portions of society from which my family came.

Surely her death served as a reminder of what she did, and you stand by every word of ‘Tramp The Dirt Down’.

EC: Of course. What she represented amounted to nothing short of class war. I’m not assuming the mantle of working class hero here; thanks to my parents I had a reasonably secure upbringing, but I have no illusions about where I came from and where we fit or don’t fit in. Do you see who’s running the country? It’s not us. Do you see who owns the country? It’s not us. Do you see who we sold the country to? It’s not us, but we already fuckin’ owned it. We owned the gas, we owned the electricity, we owned the railways. My parents and your parents paid for it, with their tax, with their National Insurance; they paid into all of those things that were a good idea, and there is no better idea. Is the idea flawed? Yes, absolutely. Was it corrupt? Yes, absolutely. Were the unions corrupt? Yes, absolutely. Was the Wilson government corrupt? Yes, absolutely. But was it more corrupt than what’ve got now? No. It’s small beer compared to what’s going on now. It’s billions and billions given to bankers to run away with.

I didn’t have a second thought about singing the song again, because her legacy is still with us. Did you see that last interview Iain Banks gave before his death? He said squeeze any of these people, any of the Blairites, any of the Liberal Democrats, any of the Tories, and the same Thatcherite pus comes out. No song I’ve ever written says it better than that.

Is that the overriding "protest", if you will, behind much of Wise Up Ghost? That nothing’s changed for decades?

EC: I wouldn’t call anything a protest record, I don’t really know what that means. What I arrived at in the lyrics, and in utilising lyrics from past songs, shares a tone that may or may not strike a chord with whoever hears it. But will it effect change, which I suppose is the dictionary definition of what a protest record should be? A song like ‘We Shall Over Come’ is clearly a rallying cry, but a lot of what are deemed protest songs deal mostly in solace, don’t they? I mean, I think the function of ‘Shipbuilding’, the reason why people respond to it now, as opposed to the events of the Falklands that inspired it, is that there’s some solace – for me, anyway – in the thought that there should be something better. The whole "diving for pearls" imagery, as bleak as that is about drowned sailors, is that when singing it you extend to the audience a sense of solace that makes it worth singing. I think that’s probably true of a few of the songs on this record as well, and in other pockets of my catalogue.

Whether or not these new songs will endure the way others have, I can’t say. In recent times we’ve been playing ‘Oliver’s Army’ with a subdued piano intro, which Steve Nieve plays beautifully, which then lends itself to a hugely uplifting feeling when the rest of the band comes in on the second verse. It’s a pretty serious lyric, but I think that’s tended to get lost in the jovial arrangement, whereas now the words are given the opportunity to make their mark with more clarity.

It’s what we’ve tried to do on Wise Up Ghost; the ideas behind the songs, no matter how many images are in them, are fairly simple. A song like ‘Walk Us Uptown’ is very straight-forward, all it asks is are we going to keep leaving it to somebody else to take us out of all of this, some kind of messiah who has all the answers? If there really is this golden future somewhere it’s up to us to find it.

Would you say there’s an air of optimism to the new songs?

EC: I think there is, oddly enough. You can’t tie a bow on what’s going on in the world, but you can identify what’s wrong and work towards something some semblance of change. That’s probably the most capable and achievable function of any protest song.

Wise Up Ghost is released on Blue Note Records on 16 September