I had just emerged from seeing Elder for the first time at the Camden Underworld venue in August 2017, when I picked up a message from my wife. It showed my mum’s back garden that night, obscured with an immense sprawling shadow. We were staying at my mum’s in north London that week.

At some point during Elder’s set, they both heard a huge crack and saw the enormous black poplar tree at the end of the neighbour’s garden topple forward. It had been a wet summer and the tree was waterlogged, and long hollowed out by disease. My mum’s neighbour emerged into their garden and exclaimed, with all the self-absorbed drama of someone aware of an impending disaster but who does fuck all about it, “Oh no – it’s finally happened.”

When a progressive heavy rock band flattens a small crowd in Camden and a tree comes down in Crouch End, that’s the Elder Effect. One thing Elder has always been is portentous, from their album Dead Roots Stirring onwards. But they’ve never been as portentous as on Omens, their new album released during a uniquely fraught period in this late-capitalist era of ennui. It is an album that seethes with what guitarist, vocalist, lead songwriter and band leader Nick DiSalvo calls “vitriol and anger and sadness” at the destruction of the world he loves in myriad appalling ways.

For all this through-a-glass-darkly pessimism, Omens is not an overbearing (nor an overly intense) album. Before, Elder’s power has stemmed from their dizzying intricacy, what DiSalvo calls “the blistering onslaught of part after part after part”. But Elder’s journey to this new one has been different.

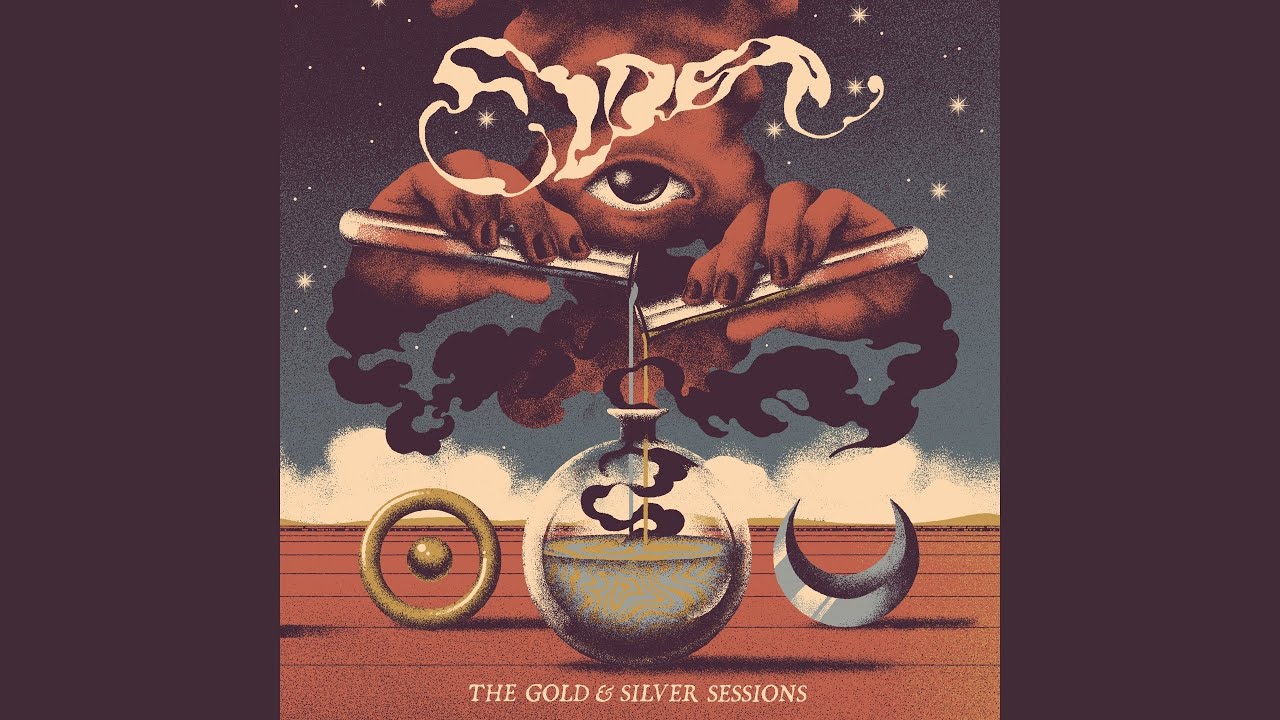

They arrived at Omens by way of last year’s mini-album The Gold And Silver Sessions, a heavily improvised live studio session and, in DiSalvo’s words, an opportunity to “take a breath and float and jam”. There was an open, relaxed-muscle quality to that record where simple melodic motifs were given more room to wander. That approach went on to inform the songwriting practise of Omens and created a new alchemy in their sound: one part anguished to two parts ecstatic.

The Gold And Silver Sessions saw Elder transmute their grandstanding stoner rock with a motorik beat and a transcendence-through-repetition mindset. DiSalvo relocated to Berlin a few years ago, hit the reset button, and started looking at his life through a different lens. 2017’s Reflections Of A Floating World was the masterpiece that followed by looking at things askance: it took inspiration from the Edo period of Japan’s history in order to grapple with a decadent society that had become untethered from notional reality. It was kaleidoscopic, dense to the point of crushing, and, like the worldview it pinioned, almost sickeningly lush.

That DiSalvo chose to thin the band’s sound out on The Gold And Silver Sessions might not be a surprise, but he doesn’t recognise krautrock as an influence: “You wouldn’t know that there was some sort of sixties rock movement going on here [in Berlin] because rock is very much not in vogue anymore. There’s not really that great a rock scene in Berlin to begin with, so unless you’re really hitting the books and trying to immerse yourself in it and see some historical sights or something, I don’t think you’d even know there had been a psych rock movement here.”

DiSalvo balks at the idea that Elder’s music has been simplified in any way. Second guitarist Michael Risberg also moved to Berlin and together they worked on the new album, sweating the small stuff and all the painstaking, meticulous shading that makes Omens‘ sound less full-on. Risberg brought what DiSalvo calls “another songwriting voice” to the work.

The album’s central track, ‘Halcyon’, opens with a four-and-half-minute section that emulated the live jamming of the The Gold And Silver Sessions with chiming guitar melodies that form and dissolve like tiny channels of water on a windscreen, before the surging waters come: “Raining down on me/ I can feel the earth”. This jam could stretch up to ten minutes in the studio, so the purported lack of krautrock influence puzzled me. I thought of Can: ‘You Doo Right’ from the debut Monster Movie, was edited down to twenty minutes but had been known to go on for hours. On ‘Halcyon’ it felt like Elder were paying homage to this philosophy.

The song itself is about trying to capture a vanishing thought, or a half-glimpsed truth, or a lost moment. Halcyon Days are associated with a nostalgic golden period of summer. In Greek myth, the Halcyon bird be-calmed the Aegean Sea so it could lay its eggs in a nest on the still water in the depths of winter.

I have been listening to Omens while exploring the hills around where I live. The first time I ventured out I was listening to this song when I walked past Halcyon Farm on a track I’d never been on before. This kind of synchronicity is sometimes referred to as a “golden scarab”. In his book Synchronicity, Carl Jung wrote about a session with a patient who was in the middle of describing a dream about a scarab beetle when a similar insect started to butt against the window of his office. ‘Halcyon’ builds to a huge conclusion. On a second walk with the album, I reached a vantage point called The Temple Of The Four Winds, as this riff swept in for the last of the song’s twelve minutes. It seemed to describe the wide vista to me as the sun began to set.

Elder have turned out a fair number of Big Riffs over the years, though their best is probably the main riff in ‘Spires Burn’: a vicious, serpentine banger that knocks you over, kicks you in the stomach, and keeps coming back for more. The Big Riff in ‘Halcyon’ stands out because DiSalvo has found them more difficult to write in the last year: “Those are really harder to pull out of my ass nowadays as a guitarist than these groovy, or even more rhythmic, chord sort of things.”

The fact this Big Riff vies with what DiSalvo describes as a John Carpenter-style synth part – one I think sounds like the opening of ‘Tubular Bells’ – is because Elder are a band who are “sometimes pushing up on our boundaries as far as a guitar-oriented band goes. And using new instruments is the best way to get new ideas and new inspiration, and new sounds.” Enlisting Fabio Cuomo to lay down synthesizers and Rhodes piano speaks to a "childlike sense of exploration" in DiSalvo’s mind, and an overt sense of journeying within their own music. Cuomo had the freedom to come up with his own parts in many instances, or deliver the polished performances of Disalvo and Risberg’s experimentation: “It’s got that fun primal element again: you hit the ‘wrong’ notes and sometimes the ‘wrong’ notes actually are cooler than the ‘right’ notes, because you don’t know what you’re doing as much,” says Di Salvo.

Elder affect changes in mood like weathermakers. The opening title track meanders gracefully, the guitars and synthesizers dancing with and apart from each other, before the storm clouds suddenly appear just after the seven-minute mark and make what sounded bucolic and sprawling suddenly monstrous, where “In the ruins tomorrow/ Lies the meaning of today”.

The cover artwork of the album by Adrian Dexter is a decaying Greco-Roman statue with a hollowed-out face. In writing an album broadly concerned with the rise and fall of a civilisation DiSalvo is aware that it’s a story that is probably exhausted (“there couldn’t be anything more played out”), but nonetheless poignant. The crumbling statue is something “everyone recognises immediately and associates with the same thing: a civilisation that got too big for itself and collapsed. And because it’s such a recognisable icon it’s the perfect symbol of what’s going on today and also to drive the point home that we’re not too big to fail. This does happen to civilizations. This has happened before and this will probably happen again.” Or, as he puts it more bluntly: “The universe is going to fuck us and then moss will grow on our tombstones.”

DiSalvo began reading Tolstoy’s War And Peace recently, picking it up again for the first time in a decade. The book impacted DiSalvo all over again, and its admonition of man’s foolishness in believing so much in the heroic or evil individual when, as he puts it, there are “innumerable forces of history moving at the same time”. In this reading, human beings can neither take the credit nor the blame: “I like this idea too that as humans we think that we have so much action and agency but really we’re just like bees all flying together but not really knowing why (I don’t know if that’s true or not, but I like the idea). It didn’t even occur to me until after the album was written, and all the lyrics too, that this was the main thing that was influencing all the themes for this album.” He gets this idea across most succinctly in the opening couplet to ‘In Procession’: “The solitary purpose/ To outshine the heavens in our minds.”

If our perceived role in life is so misguided and hopeless, why is Omens such an uplifting listen? Is it that there is nothing more life-affirming than our sense of it all ending? With its aesthetic and themes, not to mention lyrics (when did you last hear the word “empyrean” in a rock album?), Omens is a music for the decline and fall of the Holy Roman Empire and every civilization since. In Hermann Broch’s The Death Of Virgil, a modernist fever-dream novel about the great Roman poet’s final days – including arguing with the Emperor Augustus that he wants his great epic The Aeneid burned when he dies – Virgil also finds in death and decline that “the moments of essential life emerged from its twilight”.

With Omens Nick DiSalvo might have found that art is insufficient to counteract history that is unfolding in the wrong direction. “I’m watching the destruction of the world I love (and see so much to love in) by forces that – as far as I can tell – most of my entire generation wants to fight against. It wants to save our planet. It wants to make a better way of life and somehow we’re on this path as humans where we keep choosing leaders who do the worst possible things for us. I’m just watching the worst come out of humanity year after year.”

But as the chipper ‘Embers’ and strangely exultant ‘One Light Retreating’ show in abundance, Elder’s art is sufficient to the task. Pandora’s Box might be open and overspilling everywhere around us, but when I push him, DiSalvo concedes there is hope in the dark: “there are elements of hope sprinkled in with the gloom and there’s the peaks and valleys [in the music]. And I guess part of that is there is the element of hope and there is an element of the silver lining. In the grand scheme, life goes on somehow, the planet survives, a new thing happens. There’s forward movement. We may be in a downfall now but there’s something positive around the corner.”

Call it the creator’s curse, but I think Nick DiSalvo finds it hard to identify the joyousness of Elder’s sound and its curative abilities. More than many of their other releases, Omens needs time to sink in; to replenish the dead roots feeding our souls. In writing about the warning signs all around us of a global civilization on the wane – telling an age-old story about the cycles of history – Elder have created an album forearmed against its own sense of impending doom.

Omens is out now