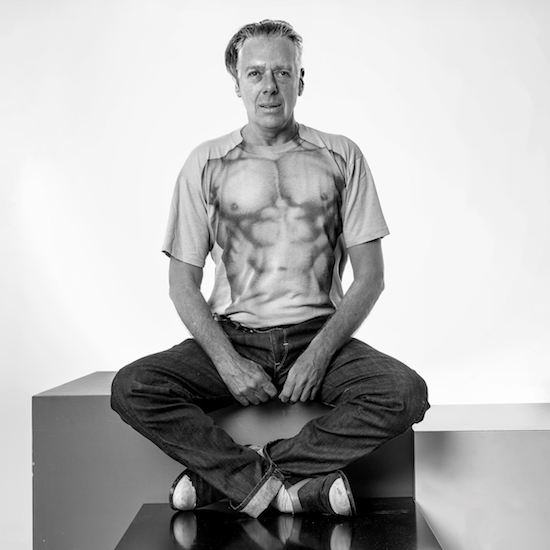

Portrait by Ari Versluis

It is often said in the Low Countries that the Belgian Eddy de Clercq is the man who “taught the Dutch how to dance”. His disco nights and dance parties from the late 70s to the early 90s were notoriously louche; a riotous mix of technical innovation and unrestrained hedonism. A restless man, de Clercq travelled widely and became something of a prophetic figure, introducing developments from America, France and the UK into the Amsterdam club scene.

The reason for the visit is twofold; firstly a curiosity born of reading his splendid memoir, Laat de Nacht Nooit Eindigen (loosely translated as Let The Night Never End). Not surprisingly for such a bon vivant his story reads as one of unabashed enjoyment. Every chapter recounting tales of disport and abandon seems to justify itself with the moniker “everyone had a good dance”. Fair do’s. The second reason is that Eddy is soon to release a compilation tape of rare and lost Dutch post punk tracks from bands who provided the soundtrack to one of his most celebrated 80s nitespots, Amsterdam’s post-punk club De Koer.

We are sat in Eddy’s basement office in Amsterdam, surrounded by records and tapes; many being recordings of his DJ-sets from the late 70s onwards. A mix from one of his new sets bubbles away on his PC. De Clercq is a genial and generous man, with beautiful manners. But one driven by strong opinions and a love of new musical trends.

I wanted to start by talking about time and place. Music innovation seems to happen when new or emerging technology influences a place ripe for something different. And often someone comes along and pulls the two elements together. Reading your book, it seems as if you have a knack of being in a specific place at a certain time and being able to exploit what’s on the ground.

Eddy De Clercq: Yes, true, but it just comes my way. I don’t know why. Sometimes I happen to be the right guy in the right spot at the right moment. I guess that my activities inspire people and that I offer opportunities without realising what is going to happen next. There was a guy I talked about in my book, during the disco era. He imported new sound and light-systems from America and the UK. At the time he was building a company called Focus, which he ran from his small student flat. I never really asked for him to come my way and say, “Look; I’ve got a big party space and I want you to deliver the sound and light system." I simply didn’t have the money for that but I got the answer, “No, I will bring all the new stuff and show you what my company can do. You will get the best disco equipment available.” And so he did, for free.

The same with a video guy, Jack Videohead. he just came up to me [at a party] and said, “I want to film all this and project it on screens during the party.” I didn’t know what he was talking about but I gave him a chance. And he came along with a crew of ten people and he filmed this party. He had these mixers and machines with him… and suddenly there was a veejay. In 1978! Until that moment nobody had ever heard of a veejay. He was doing these very psychedelic mixes of space and science fiction films, and hardcore gay pornography, and all these people dancing, or coming in and undressing, filmed and mixed live on the spot… It was amazing.

These spontaneous actions happened all the time in my life. I don’t know why. Whether it was in London, or Paris, or Brussels or Amsterdam; or in New York… I think it must be a lucky star or something, or my sensitive antenna, feeling the right vibe [LAUGHS].

You seem to get about a lot.

EDC: I travel all the time. I’m very restless you know. I don’t like to sit and count my money and be a “happy entrepreneur”. I like to move. Because that’s where the action comes from. I probably am very sensitive for energies that come together at the right moment. And that energy, I like to transform it into a party or a club. Something that becomes real.

But it’s also about fun with you isn’t it? I thought that was one of the nicest elements in your book.

EDC: Fun is the main thing. Because fun helps you transmit your message. You can only do that – transmit – when people are receptive. And people are receptive in the best way when they are together enjoying themselves in a club; with others who are on the same wavelength. Then the experience becomes a very creative and spiritual thing. That has always been my biggest ambition. To bring people together. To achieve a family spirit. Because then, you can actually do anything, because people are open to what they feel is real. That’s the main thing. People have to feel it’s real. If they feel there’s something commercial or some fake thing behind it, then the feeling is definitely different. But if you can make something genuine, then the ground is fertile for introducing something new. And that happened a few times in my life where I could sow the seeds and see something grow out of it. Be it at a party, or at De Koer or Club RoXY. That club introduced house music in the Netherlands, and once it got successful nothing could stop the growth of a dance industry that is still blooming in Holland. I mean, dance music is one of the biggest export products in the Dutch economy these days. And in the beginning Club RoXY suffered because of the house music I played; nobody liked or understood that music. I think that’s magic.

Talking of fertile ground for transcending everyday life, I enjoyed reading about the parties in the swimming pools [a series of bacchanalian riots in a public baths in late ‘70s Amsterdam]. Eddy, how the hell did you get away with such hedonism in a public baths?

EDC: Ah but you see that was what I was talking about. Fun. And don’t forget that at the

end of the 70s people were much more into wild experimentation and hedonistic adventures.

There was not really a fear of sexual diseases like HIV or aids back then, all that came later.

But you should go and see this big swimming pool. The Mirandabad in Amsterdam still exists and it’s actually exactly the same as it was. The building looks like a UFO on the outside, with a huge pool, and a big stage in the middle. When I entered the pool for the first time I immediately thought, “This is a big, big party place.” It [the space and party] was like just… mindblowing [LAUGHS]. Fifteen hundred people in this place all together. And then we just said, “Guys, right now we’re gonna have a disco party!” [LAUGHS]. Wow! Those parties were a bit over the top for the Dutch you know. The wildest mix that Amsterdam had to offer, mostly naked people dancing, swimming, having sex… And I must say, it was not just the Dutch; there were a lot of Germans and Americans, and Italians and French. You must remember that my party crowd was very international. A great mix of all nationalities. And also, stray gays of all colours [LAUGHS]. But what does that matter? Everyone brought something to the party that made it unique.

Your parties in the late 70s really seem to have lit some kind of creative touchpaper in Holland. I once interviewed Rob Scholte [the famous painter who started as the singer in great Dutch post-punk band The Young Lions] and he talked about one of your disco parties at De Brakke Grond. Rob said that he first encountered the concept of postmodernism in the flesh (so to speak) at one of your parties. In the form of a punter who deliberately wore a normal white tee and Levi’s whilst everyone else was dressed up.

EDC: Well, I think all that is because I don’t like cliques. I used to go out a lot in London with friends. And London can be very cliquey. I mean if you don’t belong to one set you don’t go to a particular party. That kind of thing. I used to go out with big fashion people from Body Map, Boy George, Blitz Kids like Princess Julia and designer Rifat Ozbek who introduced me to John Maybury, the filmmaker who did the documentary on Francis Bacon. I was in London when he was working on that. Anyway, I was hanging out with people like that, and others like Rachel Auburn and Leigh Bowery. Just amazing people. But their world was cliquey, you were in that circle and they took certain sorts of drugs and went to certain parties. And the only thing they weren’t cliquey about was sex. I mean some of them went to saunas and parks and had wild sex. But not in their circle. I always found that very difficult to understand. So I used to butterfly around with other friends who were in a totally different world.

But the world of De Koer [the famous post-punk club in Amsterdam that Eddy set up in 1981] was also very cliquey though wasn’t it? And it wasn’t a big scene was it?

EDC: The scene wasn’t big in Holland as it was still in its embryonic phase. The punters were looking to what was hot & happening in clubs like Blitz in London, or parties in Berlin. But Amsterdam is not Holland. It is a city that attracts people from all over Holland. And lots of international tourists and party people. That was De Koer’s audience. And one of its main attractions. There were a lot of artists who came to the club after performing in Paradiso or de Melkweg. I’m talking bands like Depeche Mode, Blixa Bargeld from Einstürzende Neubauten and Lydia Lunch, who became regulars when they were in town. And of course that attracted the locals. As I say in the book, it was a total mix, a salad bowl as I prefer to call it, and that mix gave the club a character. It was punk, new wave, disco, electro….anything really. Plus it had all these social “tentacles” reaching out towards art, music, fashion, punks, squatters, just anyone. You know, people working in the Hema [a department store in The Netherlands] and very chic people together, bankers too. It was fantastic. I am very proud to say that this was the only place in Amsterdam where that mix happened. Mazzo [another famous post-punk nightspot] claimed to be like that. But Mazzo claimed that you had to be artistic to get in! Quite pretentious really…[LAUGHS].

So you saw all that punk/post-punk world as inward looking in Amsterdam?

EDC: Remember that I’m a foreigner. I was born in Belgium and moved to Amsterdam when I was 17. I am not a Calvinist Dutchman but a Catholic Belgian. I think that makes a big difference. Many people stayed in their own scenes back then and didn’t mix. Not many out of the hardcore Dutch punk or post punk scenes went to De Koer that often. Even nowadays some people see me as a “vreemde eend in de bijt” [translated literally as the strange duck in the pond. In other words, an outsider]. But I was there right at the beginning mingling with the fashion crowd at the Lady Day shop, and then came my own disco parties at de Brakke Grond club. At the end of the 70s I created something that set a sort of momentum.

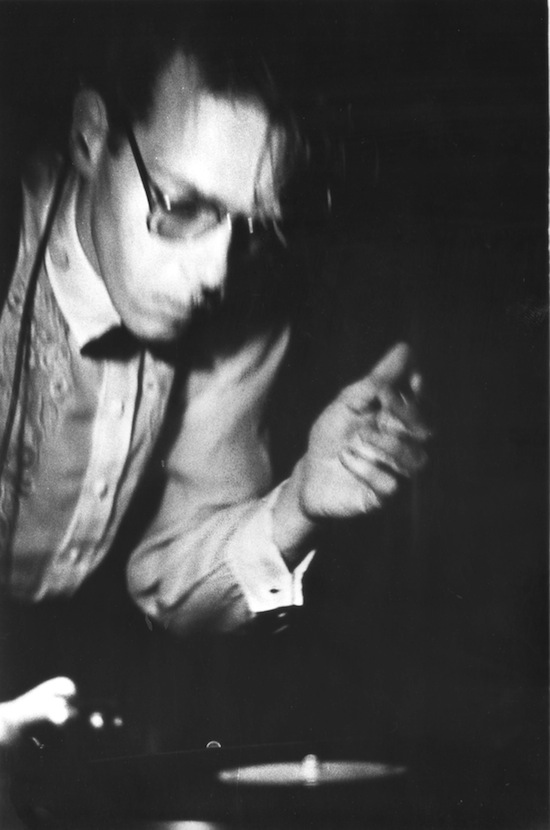

Eddy de Clercq DJing at de Koer in 1982

Dutch DJs are very celebrated in The Netherlands nowadays. To be fair that is the case with other countries or cities. But – in essence – what has house music or dance music got to do with anyone’s nationality?

EDC: Well, in the beginning it was very nationalistic also. I was having this discussion with a few English guys way before house; back in the 70s at the Amsterdam Dance Event. Forget what you have heard, the Amsterdam Dance Event didn’t start fifteen years ago or so. I believe it started in 1979. I went to the first dance event in the RAI [a big exhibition centre in Amsterdam] with three hundred people there, mainly foreigners. And I remember a discussion with a panel of experts, I asked a question to one of the moderators: “Why is it so difficult for a foreign DJ to play in a club in London?” And you know what the guy said? “Get better than the English."

But when you hear the music of these celebrated Dutch superstar-DJs nowadays… my God, I wouldn’t even feed their music to my dog. I don’t consider that to be my sort of dance music. The latest trend seems to be these DJs doing pre-recorded sets, in perfect pitch with the lights & acts on stage. Everything is centred around the action from the stage. It doesn’t even demand action coming from the crowd! Passive consumerism or something. Mayhem with an overwhelming sound that isn’t actually good music. More like diarrhoea.

Check out Seth Troxler who has defined E(lectronic) D(ance) M(usic) culture in an amazing and honest open letter from May 2014. One of his stand out quotes is, "Let’s face it, EDM Dj’s are the worst people ever." But this [Troxler’s] manifesto isn’t just about the Dutch DJs but EDM worldwide. And I think that is more interesting. The Dutch invented the genre and exported it all over the world. So you could say that the one who comes first and knows how to make it successful will make the most money out of it. And not just the DJs. Dutch Dance is one of the biggest export products nowadays for The Netherlands. That’s a fact.

There is some great dance music about, though.

EDC: if you just take the time to look, then yeah, you will find some really great music in Holland. Just scratch the surface and look underneath the corporate surface. It’s like that Indonesian cake, spekkoek, with the layers. And that’s what is happening with dance music right now. Once you cut into that cake you see all these different things going on. The sad thing here is that most of this innovative new music doesn’t make money so it’s regarded as uninteresting for the business people and considered as “underground”.

There are so many international musical connections here, in Amsterdam. And some of them are amazingly successful. The way Electronic Dance Music [EDM] is manipulated and exported to the world is a very strong, and “total” concept. But it’s not that interesting artistically. EDM is seen by some media as a kickstarter for kids who have no idea how deep dance music can go. In the US, EDM has the moniker, “3D” [Dames, Dollars & Drugs] since it is such a commercial success. In Europe I see the scene slowly changing. Antal [Heitlager] of Rush Hour is a great promotor and dj, Canvas already had a steady following but now De School and Radion, are just a few of the underground clubs that opened last year. And the number of outdoor festivals is growing each year. Dekmantel is one of the new festivals, really interesting and innovative.

You talk about the attention for commercial success here but perversely, the Dutch are great at avant garde music. I think it’s a fantastic time for good avant garde music in The Netherlands. Some great acts: Dead Neanderthals, things on Barreuh Records, Moving Furniture Records, noise like The Julie Mittens, lots of ambient/drone artists like Machinefabriek or Martijn Comes. And of course The Ex. Yet this stuff only gets discovered abroad before it does well here.

EDC: Ah you mention The Ex. The Ex is an important group of people in Holland working for a long time. Really good musicians, and their related recordings and projects are as equally important. One of the few Dutch bands I really follow. And then there is Jungle By Night who play great Afro fusion. And have you heard Amber Arcades? Yeah, Holland is very good at avant garde, probably due to the Dutch character. Good at design. Experimentation sometimes works here very well. I mean, the Dutch have a can-do mentality, anything is possible. As long as you pay for it [LAUGHS]. It is very capitalist. Quite American in a way.

On a slightly different (capitalist) tack, and to go reference your book again… I have a theory, that “traditionally” a lot of musical revolutions start with, or round shops. Just take punk. You’ve got the Sex and Seditionaries shops, or Probe in Liverpool. And to go back to your book, a lot of things seem to start in shops for you. You talk about going to Biba in London, or working in Lady Day in Amsterdam. You also had your own vintage clothes shop in Ghent. The idea of having the shop is important. The small commercial enterprise.

EDC: Shops and clubs are very important when you want to change things. And they have a common denominator; the customer. A scene can be created when people are coming together. Either to shop or to hang out. You can see this happening right now with the success of Rush Hour in Amsterdam. I mean it grew from a very small shop, not much bigger than my cellar but, man! Now the shop has several own labels, and a worldwide distribution network. The size and look of their new location and the click between the customers and staff is just amazing. A beautiful place. I think that is a great, great thing, to create your own identity and foster a true family spirit. Remember Biba in my book? I’m not writing about Biba because it was such a fantastic fashion shop. No, man… that place represented a style and spirit. Biba was more than a physical shop in a high street; Biba was an identity back then. You could meet someone in the street wherever you were, in London, or Paris, NYC and you could see that they went shopping at Biba.

It’s also funny how you seem to be able to go easily from the shop into your nightlife activities.

EDC: Ah but for me nightlife is like everyday life’s mirror. In the daytime, you act the way you should act because that is what people pay you for, or want from you. But in nightlife you can do anything you want, because that is the fantasy life, the opposite of your daily life. Everything – except violence – is tolerated. And that is why it is so surrealistic in a way [LAUGHS]. When you go to a club you can talk intimately to strangers you have never met before. And they will tell you things that will be shocking to hear. Because, on the whole, people behave honestly in this situation. At the same time they can be very false. What is “real”? Who can control it? It’s a great way of testing fantasies and exploring new frontiers. In your daytime life you have to be more strict.

I suppose then that’s how your clubs worked?

EDC: Yes. And you know what? In nightlife you can become a star, while in the daytime you can just be a nobody. I remember this guy, a famous, larger-than-life character who used to come to the RoXY, before that he was a regular at my parties in the Mirandabad. This guy lived like a mouse during the day. I think he was a painter. But the minute he stepped into Club RoXY, he undressed, and walked around proud and nude. I’m talking the full monty. The guy was actually very good looking with a great body, he had a huge dick. I mean, quite well hung. He was famous for that. And everybody was like, “oooh!” Especially the queens, they were like, “Oh my God! he’s gorgeous!” When he put on his clothes no-one even looked at him. But when he was nude in the RoXY he was God. That is a good example of what I mean about living out your fantasies at night time. And in my club he wasn’t going to be arrested for it! [LAUGHS] I know he wasn’t a flasher, just a totally weird guy.

Let’s talk about New Beat. That has been credited with having an influence on house in Europe.

EDC: Well, New Beat was happening in 1985, 1984… way before house broke in Holland. I remember going to the record stores in Antwerp to buy music. First of all their selection was so peculiar. I heard records there that I had never heard in my entire life. And the DJs were selecting this weird mix, from obscure crooners up to industrial noise, and it was selling like hot cakes because these songs were very rare and influential. You talked about a store setting a scene, well that store in Antwerp built a sound. USA Import was the first store where a specific new sound was happening. Because the people working there were mostly DJs who had access to radio shows, which was very important to spread this new gospel. Every week there was a show in Brussels called Liaisons Dangereuses. The broadcasts were totally unchartered territory, a different world and I couldn’t believe the music. Then at night we went to the Ancienne Belgique in Antwerp where we could see people dancing to the music, taking drugs to it. An apocalypse on a dance floor. It was magical! [LAUGHS]

The tempo of New Beat is quite low, around 100 BPM, not like disco which is normally pitched at 120, and it is important that the deejays keeps it at that exact tempo. Only then does the sound become very much like a drone, heavily computerised with little “human elements”. A dark atmosphere with vocals, computer voices a la Kraftwerk. The paradox was that at the same time a song like ‘Elle Et Moi’ became an iconic New Beat track, sung by a real crooner [Max Berlin, a French producer and the brother of Cerrone].

It was his only hit and it came into the mix when the DJ had been playing this mechanical drone music for hours and hours, and then suddenly the lights go down, and the whole place goes totally black. And you hear this deep sensual voice crooning “Elle… et moi” over a minimal soundscape. I still get shivers from that, fuck! [LAUGHS]. I mean it’s fucking…

Surrealistic?

EDC: Exactly, surrealistic. And then the DJ goes back into this heavy machine sound. And I would wonder, where on earth could a DJ come up with this selection? And create a totally new sound out of it? Now, I believe that the Belgians do possess some surrealistic gene.

Tell me about when you kicked off the RoXY

EDC: Well, that was a different thing. The general public wasn’t familiar with house music yet. There were few shops in Amsterdam selling that music, it wasn’t played on the radio, there were no DJs besides myself and a very few other guys in Amsterdam, Den Haag, and Eindhoven. In Amsterdam there was Soho Connection, a group of English friends and these funky-punks, Abraxas and Jeroen Flamman, who were into House music. Why? because Abraxas is a black American queen, and he knew it from back home. But in Amsterdam the situation was very different. So the RoXY had a big image problem, also because it was a club, made of bricks and mortar. Don’t forget that Acid House in the early years was happening in warehouses and unusual illegal locations (like tunnels/boats), not in clubs. It was considered to be very snobbish to go to clubs at that moment in time.

I’m talking about clublife in 1987 in Amsterdam, and 1984, 1985 in London; with initiatives that happened after the reign of Blitz Club, with Heaven as the “pinnacle”. But the real excitement was happening underground, with parties like Shoom and Danny Rampling. I remember one night gathering at the back of a train station where about ten buses were waiting. Then we drove out of London, after an hour or so we arrived at our destination; a big shed on a farmer’s field in nowhere land. Here I experienced one of my first raves, with Danny Rampling. Although acid house was exploding in Ibiza, Belgium and the UK, making Club RoXY successful was tough in the first year. First of the club had no identity yet, no clear music policy and most of all it was quite difficult to become a member, 200 guilders for a year membership was expensive for most punters. Everybody seemed to prefer the free squatter parties in a tunnel I guess.

What made RoXY popular in Holland?

EDC: I don’t know… my policy has always been to play new music. New beat, industrial, techno, disco, funk, rare groove and house music. Of course I knew disco and dub from years before but I never heard such a radical new sound like house. It blew my mind! But why didn’t it work at Club RoXY in the beginning? As I said, there was no scene, no DJs nor radio, and then Amsterdam showed itself to be the very very conservative the city can be. Finally the magic happened during the second summer of love, or the autumn of love as I prefer to call it, in 1988.

But before we opened the club we were working building the club. It had to be built in this old theatre. We had to build the place, a full year before we opened, 1986 to 1987. And I went to Belgium and to Paris, I could see things growing. But here there was a void. You could feel it growing outside Holland. It was not happening in Amsterdam, and that was weird. And I remember standing in RoXY, out of my mind. Not because of drugs, but because I was so tired. I was really so desperate for the crowds! I remember standing in front of the widow at the top of the building. I remember opening the window and shouting out, “Amsterdam! Where the fuck are you?”

Eddy de Clercq releases De Koer 1981 Demo’s & Live Recordings on Testlab. His [Dutch-language only] autobiography, Laat de Nacht Nooit Eindigen, is available via Bas Lubberhuizen