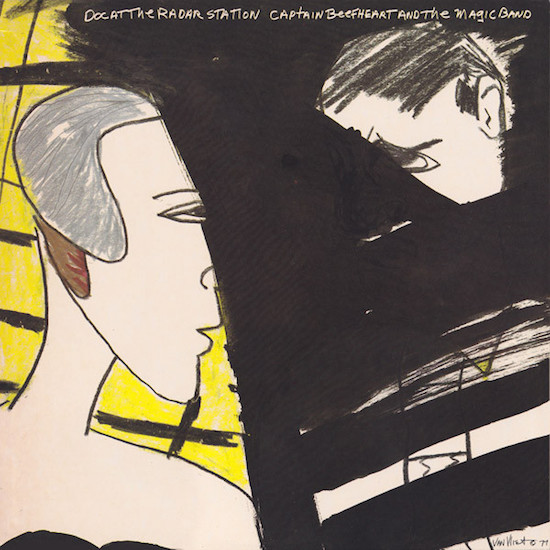

With a recording history spanning 16 years from the first Magic Band single in 1966 (a cover of Bo Diddley’s ‘Diddy Wah Diddy’) to his final album, Ice Cream For Crow in 1982, Captain Beefheart (AKA Don Van Vliet) inarguably remains one of the most enigmatic and influential figures in music.

Like a lot of people of my generation, listening to John Peel’s mid-’80s BBC radio show was instrumental in my musical education. Bands like The Pop Group, The Birthday Party, That Petrol Emotion, Big Flame, The Fire Engines, The Wolfhounds, and the earlier more angular Soft Boys of Can Of Bees, to name but a few, were all heavily indebted to Beefheart’s surrealistic and discordant take on Black American blues music.

Tom Waits too, from his more experimental era, beginning with 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, was hugely influenced by Beefheart. A 1988 Beefheart tribute album, Fast ‘N’ Bulbous, featured cover versions by Dog Faced Hermans (featuring a pre-The Ex Andy Moor), XTC, The Membranes, Sonic Youth, and The Scientists. Indeed, so strongly was his essence felt across the sphere of alternative music, that perhaps only The Velvet Underground, The Beatles and Syd Barrett could be said to operate at a similar level of sonic influence.

Beefheart’s third album, 1969’s Trout Mask Replica, remains the ur-text of experimental rock music, a radical shift in perspective comparable in some respects to the invention of abstract art in painting by Wassily Kandinsky, or Hilma af Klint.

Born of a difficult process of dictation by piano (an instrument in which Beefheart had no training), under conditions that some would liken to living in a cult, Trout Mask is widely considered to be his magnum opus, with famous advocates including David Lynch, Matt Groening and John Lydon. It is also his most difficult record, with sublime moments (such as ‘Ant Man Bee’) appearing alongside tracks that to this day retain the capacity to instil The Fear in me, like the terrifying ‘Pena’.

Occupying similar territory to its predecessor, 1970’s Lick My Decals Off Baby also has its champions, but despite highlights such as ‘Doctor Dark’ or the stunning cacophony of ‘Flash Gordon’s Ape’, it’s a far more uneven affair. Clear Spot (1972) is widely regarded as the best of the ‘commercial’ Beefheart albums, and has much to recommend about it, despite its sound being perhaps too identifiably of its time.

Unconditionally Guaranteed and Bluejeans And Moonbeams (both 1974) heralded the ‘Tragic Band’ era, after the entire Magic Band left and were replaced by session musicians. A tour with experimental UK band Henry Cow during this time only served to cast this attempt at commercial success into even starker contrast.

Bat Chain Puller could have been a worthy return to form in 1976, had it not been hampered by legal difficulties which delayed its release until 2012. A new band was assembled, and several songs from the previous unreleased record were re-recorded for 1978’s Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller). The album was relatively well received, although some members of the band expressed reservations, particularly concerning the re-recorded material.

In the 2006 Beefheart documentary Under Review, keyboard and bass player, Eric Drew Feldman, said: "At the time, I thought it had its peaks and its valleys. I would say that I had more anxiety than pleasure about it. I felt more at ease and successful with the album that came after it, Doc At The Radar Station."

Recorded and mixed quickly, with 12 tracks clocking in at a relatively short 38:52, Doc is infused with an irresistible, ecstatic energy. In Under Review, guitarist Jeff Morris Tepper claims that he found most of the albums he recorded with Beefheart to be less exciting than their rehearsals, due to lengthy recording processes lessening the material’s power and spirit. With Doc, Tepper believes, the band had finally caught that original fiery quality. Without a single subpar track amongst the 12, and three or four contenders for the highlight, this is the Beefheart album that has spent by far the longest time on rotation on my stereo and the one I will always play first for the uninitiated.

Following two abrasively stomping opening tracks, the instrumental ‘A Carrot Is As Close As A Rabbit Gets To A Diamond’ is a thing of brief but undeniable beauty, as well as a perfect illustration of Beefheart’s use of the natural world just ‘outside’ of our own human heads. ‘Sue Egypt’ makes brilliant textural use of Feldman’s Mellotron, an instrument more usually associated with progressive rock, but here utilised in an entirely different context. The frenetic strumming and stop/start rhythm of ‘Dirty Blue Gene’ evinces the kind of crazed, runaway burst of energy that the likes of Big Flame and The Fire Engines could only emulate in their wildest dreams.

‘Flavour Bud Living’ is an incredible ‘exploding note’ guitar solo, and one which set up Gary Lucas’ future career, which would later see him working with such iconic musicians as John Cale, Nick Cave, David Johansen, Lou Reed and of course, Jeff Buckley. At 6:34, clocking in as the longest track on the album, ‘Sheriff Of Hong Kong’ exploits a thrilling tension between a droning, dirty sounding guitar, pumping drums and the sonorous splashes of sound issuing from Beefheart’s crashing Chinese gong strikes.

Perhaps best of all, album closer ‘Making Love To A Vampire With A Monkey On My Knee’ sets Beefheart at his wild, poetic best against wheezing soprano sax, a rhythm section that sounds like it’s falling down a long series of steps in choreographed yet chaotic perfection and joyous Mellotron swells that sound like frothing ocean waves.

Beefheart’s manager at that time, and special guest as guitarist on ‘Flavour Bud Living’, Gary Lucas, recalls: "It was a stunning comeback. I feel very blessed because I helped him midwife the thing into the world, in a dual capacity. I had this dream to play with him since I’d seen him live in New York in 1971. I thought, ‘If I ever do anything in music, I want to play with this band.’ So he asked me to learn this music, which I did, and at the same time, he said, ‘I want you and your wife to manage me, would you do that?’ I agreed to help him, and I think we did a very good job.

"As far as doing the press and publicity, getting the message out about him, I got a lot of the key critics, who were based in New York to come round to the flat in the summer after we mastered the record. The best compliment I ever got was from Lester Bangs. He heard the piece ‘Flavour Bud Living’, which was my little guitar showcase. He said: ‘Gary, what part are you playing on this? Are you the top or the bottom part?’ I said: ‘Lester, it’s all me, in real time.’ So I thought that was pretty good, to have confused the great Lester Bangs.

"Then it was a wonderful tour we did, up and down the UK. We went to the continent – France, Belgium and Holland, and back to the US. A lot of great shows. That gave me the bug to want to do this full time. I loved it."

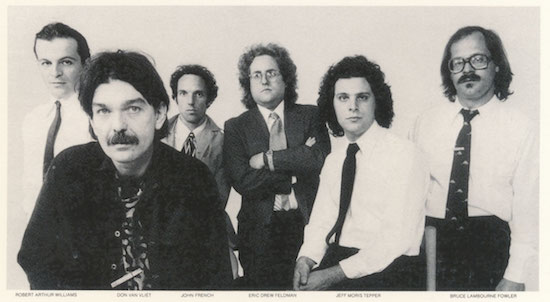

Van Vilet and Lucas at the Doc sessions at the Soundcastle, Glendale by Glenn Kolotkin

Talking about Van Vilet’s notoriously controlling side, he said: "I felt the persona when Don would become very authoritarian and then I saw little Donnie, because basically he was like a big overgrown kid on a good day, and super friendly. If you talked to him on a one on one, you’d come away thinking, ‘This guy is the warmest, kindest, most magical conversationalist.’ Right there and then he’d entertain you with these leaps of free association. It was like talking to James Joyce, or Ulysses come to life, with word play and puns.

"I played like three or four numbers on the Doc shows. Then I was his buddy, his minder, as the co-manager, with my ex-wife Ling. But it was difficult. As Don would say, ‘I displace a lot of water, man.’ Every morning was an epic battle to get him from the breakfast nook in these cheap British hotels and get him in the van. He drove the tour manager crazy. He was a very nice guy, named Bob Ward, who played with Kevin Coyne. He was our driver. He’d go, ‘Don, we need to get to the next town, so we can do our sound check.’ And Don would be like, ‘I don’t need my sound checked man.’ And [even] if he did do a sound check, he’d just go up to the mic and be like, ‘Gaahh.’"

During this UK tour it had already come out that a lot of the leading lights of punk had claimed Captain Beefheart as an influence. He says: "I think there’s a certain raw energy about Doc that’s as close to a punk statement as Don ever made. But when we toured, Don was in one of his moods, because even though a lot of avatars of the first wave of the punk movement, like John Lydon, David Byrne, Joe Strummer, Mark E Smith of The Fall, all gave him enormous props as an influence, he felt like he was the one that got the short end of the stick."

The fact that he felt these younger musicians were reaping benefits – financially and otherwise – by leaning on his talent can be seen in the lyrics to ‘Ashtray Heart’: "You used me like an ashtray heart/ Case of the punks/ right from the start."

Lucas recalls an incident that displayed just how unpredictable Van Vliet was when talking about other artists’ music. At the last gig of the tour at York University, a journalist asked if he liked any of the current crop of "punk or new wave" music: "Don told him, ‘Yeah, there’s one band I think are really good. And that’s Throbbing Gristle.’ It was hard to predict what Don’s taste would be on any given day and honestly I found that in general, he was dismissive of a lot of stuff unfairly, I mean I’m not even sure he actually listened to some of the stuff he criticised.’

Which brings us neatly on to Tom Waits… Lucas remembers: "Many times, Don would talk about Swordfishtrombones… ‘Doesn’t that remind you of something?’ When we were doing Ice Cream For Crow, Waits called the studio a bunch of times to talk to Don and pick his brain, like, ‘What engineer are you using?’ Don gave him some bum steers. He said, ‘You gotta use this guy, Rudy. Check out Rudy.’ Rudy was this older, Black guy that Don knew when he was running in Hollywood as a teenager. Rudy was a tape operator. He made safety masters, that was his job. He was not a recording engineer. I guess Waits hired Rudy to do a session. I don’t think he got the results that he wanted. [Laughs]

"I like Tom Waits and I can definitely hear the Beefheart influence, vocally and musically on that album and some of the later ones. But Waits was always very generous – always giving Don props in interviews. Don was like this with everyone. When Charlie Daniels, who died this year, came out with ‘The Devil Came Down From Georgia’, Don said, ‘That’s my song, ‘Floppy Boot Stomp’.’ He heard The Police song ‘Mother’ and he said, ‘That’s my song, ‘Telephone’.’"

Don Van Vilet, it turns out, had more time for Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. And, according to Lucas, he had more time for dead musicians than living ones: "He knew good music, but he did have a tendency, if you were alive and making music to be overly critical. Once you were safely expired, he was a little bit nicer. When he played New York, the free jazz community came out to hear it, the music of Trout Mask and Decals. Rahsaan Roland Kirk was his biggest fan. Apparently Kirk would wake up at one in the morning and say, ‘I gotta hear Trout Mask Replica!’

"Don got a lot of respect out of the Black, free jazz community. They all came to check him out because they knew it was great music. At the time of Doc, we didn’t see so much of this but Don would love to listen to that music and certainly, he owed a great debt to Black American blues, no question."

As Mike Barnes notes in his excellent Captain Beefheart: The Biography: "Van Vliet saw this new radicalism [of punk at the ‘new wave’] as little more than rehashed rock ‘n’ roll… [his] universe was a solipsistic one. As always, he had to feel, and be seen to be unique." Considering Beefheart’s antipathy towards those who proclaimed his influence in their own music in relation to Doc provides a useful perspective in a number of ways.

First of all, it’s immensely satisfying that Beefheart was able to return his music from the ‘Tragic Band’ period of the mid-’70s to the artistic heights of his avant garde era, with a younger band, in a more succinct form than Trout Mask and with a higher success rate than Decals. Secondly, despite Beefheart’s disinterest in punk and new wave, on Doc he clearly demonstrated that he was still capable of producing work that surpassed the vast majority of the music that was being made with a distinct ‘Beefheartian’ influence by musicians he had himself inspired.

Bassist and keyboard player on Doc, Eric Drew Feldman, recalls the album’s composition process: “We recorded everything in less than two weeks, then went in and it was mixed in a third week. It’s one of those warts and all records as a musician but I have learned over the decades since then, that that’s my favourite kind of stuff and that’s part of its charm. Don was pretty good at figuring out who was around and what parts would suit them. He’d come over and Morris [Tepper] would come over and he would just go into various songs.

"I had this home organ in the living room, which was out of a funeral home, and he sat down and played what became the music, at least the keyboard parts, of ‘Sue Egypt’. Other songs came from piano parts that I figured out. I tried to take on the role of a John French character. ‘Sheriff Of Hong Kong’, I transcribed the best I could and exactly as he played it. Then we got together with Morris and went through it a bar or a riff at a time. Some parts were old cassettes of things he had written in the past. Or a song he had recorded in an earlier fashion, with an earlier band that never came out."

Feldman describes how ‘Best Batch Yet’ fits into this category even though it went through a quite pronounced evolution: "We figured out what he wanted and played it over and over again and it was fun for us to rehearse it and learn it because it was a nice bit of music to chomp down on and play. We learned it really well and then went in to record it. We played it a couple of times, feeling pretty good about ourselves. And Don came out into the studio and said, ‘Hold on a second.’ Then he said to one of us, ‘What you’re playing there, play it backwards. Play it around. Change it.’ He did that to each one of us for a while.

"He was our leader and we didn’t argue, but basically he was just cocking the whole thing up and we were trying to do it. We were trying for 15 minutes or so, then he went back into the control room and finally he hit the talkback button and said, ‘OK, go back to the way you were playing it before, but play it the way you’re feeling now.’ Because we were all kind of on edge and he wanted that angst in there and we were making it too nice.

"Some people, their brains are advanced enough to know this in advance. Most musicians aren’t. I still work as a musician, but as a producer I try to instil a lot of this concept into people. They’re often doubtful about it but they come around. When it came to playing the stuff live, We weren’t really encouraged to improvise. It ended up being always different anyway, because Don was always the wildcard. He would always do it different and it was up to us, most of the time, not to try to stay with him.

"As for Don’s attitude towards others who claimed he had influenced them, he was suspicious. He never really gave anybody much credit, although later on in life he seemed to mellow out and like things more and comment about it. Back then, if we had things like special tunings on a song for the guitar or bass, of course musicians would come up to us, fairly well known ones, after a show and they’d be enthusiastic and start asking questions like, ‘What tuning is that?’ And we were instructed, ‘Don’t tell them anything, they’re just trying to rip us off.’

"When I first heard Don, I had not heard Howlin’ Wolf, then of course somebody played or I stumbled upon it on my own, and went, ‘Oh, there’s a certain similarity there’ to one of Don’s voices – Don used many voices. Then when I said it, Don got uptight. I know that he loved Howlin’ Wolf, but he would tell me that his favourite singer was Jimmy Durante – The Schnoz – who did comedy songs. Don would be like, ‘Jimmy Durante is the best, that’s where I get my inspiration from.’

"He would say he would get his inspiration from almost non-musical things a lot of the time. I know that he really liked Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and Kirk was really into Trout Mask. One of my biggest regrets was at one of the first shows I was going to play with Don up in the Bay Area, in 1977, and Rahsaan was supposed to come to the show and was going to sit in. But it didn’t happen, I think he was sick. He did die very young. He must have been near the end then.”

After Doc, Beefheart would make one more album before announcing his retirement from music and his intention to concentrate on painting full time. For Ice Cream For Crow (1982), Lucas became a full time band member, whilst Feldman, who had already committed to touring with former Residents guitarist, Philip ‘Snakefinger’ Lithman, only played on one track, ‘The Thousandth And Tenth Day Of The Human Totem Pole’. The album wasn’t as well received as its predecessor. Whilst there’s still a lot to recommend on it, Beefheart’s largely spoken/ranted word vocal falls a little short of his inspired singing performance on Doc and there’s a certain unevenness to the quality of its tracks.

According to Lucas, Virgin would have happily backed another record, but Van Vliet’s interests now laid elsewhere. He had been discovered as a prodigy sculptor as a child and had been painting for much of his adult life – unsurprising, since his music was so painterly in its touch.

Lucas recalls: "It was very disappointing for me. I went out with him one last time to help organise the extant painting and drawings that he had in his attic. Making notes, cataloguing pieces, sizes etc. I said to him, ‘You know, Virgin would roll another record.’ He was just burnt on music and wanted very badly to get into visual arts as a way forward and he also said to me, ‘I think art goes way beyond music.’ I said, ‘Yeah, but you are one of the most genius composers of all time.’ And he goes, ‘I think my art is way better.’

"I love his art, so I wouldn’t contradict that for anything. If you know his art, basically a lot of it centres on beautiful renditions of animals. He was very ecologically minded, before it became fashionable. If you go to lyrics, especially from the Trout Mask/Decals era, for instance, there’s a song called ‘Petrified Forest’. They’re warnings about what’s going to happen, ‘The rug’s wearing out that we walk on/ Soon it will fray ‘n we’ll drop/ Dead into yesterday… If the dinosaur cries with blood in his eyes/ ‘n eats our babies for our lies/ Belch fire into our skies/ Maybe I’ll die but he’ll be rumbling through/ Your petrified forest.’ A lot of cautionary stuff."

Feldman, who went on to work with Pere Ubu, The Pixies, PJ Harvey, dEUS and the Polyphonic Spree, and most recently produced and played on the new Residents album, Metal, Meat & Bone, remembers: “After Doc, all kinds of gigs were being offered, really big gigs, but he was not interested in any of it. It’s only for me to guess but maybe he was starting to feel the effects of his illness. As far as I knew, that wasn’t yet diagnosed.

"For Don I have to admit, his first record was ’65/’66 and now we’re talking 1982, that’s about 16/17 years. There wasn’t an alternative scene yet and he kind of suffered for it. I think [as] time goes on, his influence is almost less obvious because it’s been so long that I think people now are being influenced by people who were influenced by Don. So they’re getting it the next time around.

"There’s a lot of pretty angular music that I think has the influence. You know, for a while, even me being who I am, when I set out for many years I became a producer, I got some gigs because I wasn’t the most famous producer around that they were considering but I had played on a couple of their favourite records, which turned out to be the Beefheart records I had played on. So I might be everybody’s second choice, but I was on everybody’s list. And the other people were only on two lists or whatever, so I would get the gigs. And I’ll always be grateful for that."

Gary Lucas has been regularly performing live streaming concerts from his living room during lockdown, including tributes to Captain Beefheart