There is something quite jarring about meeting Denzel Himself somewhere as mundane as the Eat off Old Street. The emerging South London artist’s oeuvre includes rap, production and directing his own visuals, and it’s these visuals that I’ve been up late watching the night before our interview: eerie, distinctive aesthetics that toy with perceptions of beauty and bodies. (On the promo for ‘Chevi’ he appears disconcertingly eyebrow-less.) All disorienting DIY close-ups and split screens, underpinned by a raw and thrillingly feral kind of rap music, tracks like ‘Bangin’ hear him metal-screaming through his gold-capped teeth before his friends carry him away like pallbearers. Denzel is among the most innovative young artists coming through in Britain right now, rightfully being touted as one of the best in the country’s growing alternative rap scene off the back of last year’s Pleasure project.

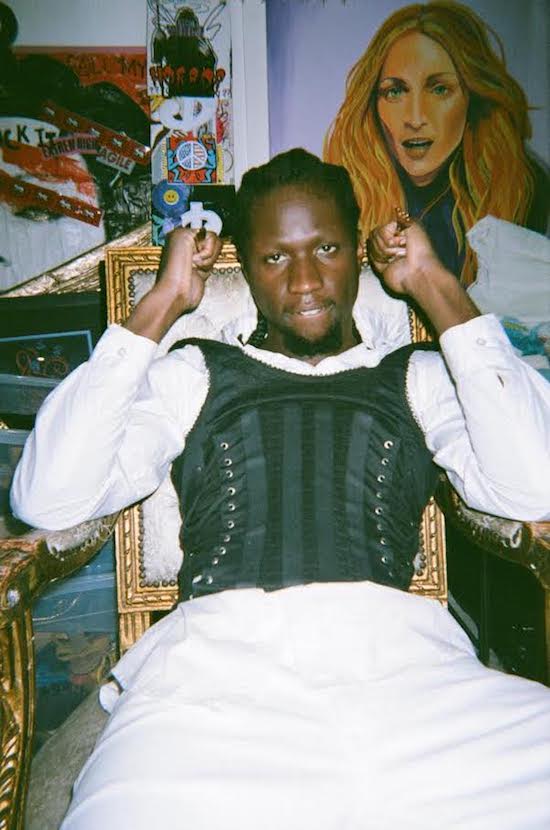

So chatting nicely in a chain café about normal things like being vegetarian (he is very suspicious of Quorn) feels, understandably, somewhat surreal. For his part though, Denzel seems unphased by our surroundings. Dressed all in black (with his eyebrows now back in situ), he chats amicably and thoughtfully throughout the interview.

Denzel is expressive, but will never say more than he feels is necessary – he reveals when we are about to part that his new EP is called Baphomet James, but refuses to expand on why. This release is something of a change in direction – there is more in the way of mellow, Dilla-style production than before, enriched with howling flourishes of brass and strings. But replete with echoes and glitches and low-key groans and scratchy screams, it’s just as mind-bending as you’d expect.

Ahead of the release and a UK tour, here’s what Britain’s rising auteur was willing to disclose over paper cups of tea.

So you come from a film background, right? How did you get started in general – did making videos happen first, or did the music start first?

Denzel Himself: Okay so, when I was 17 I studied film production, and at that age is when I started producing beats, and when I started recording as well. So producing, rapping, singing, direction… whatever… has all been happening at the same time, and they’ve all informed one another because I’ve done them all together at once.

Are there any particular influences for you visually when it comes to the film side of things?

DH: The funny thing is that I don’t watch a lot of films, and I haven’t watched many films, because it’s just difficult for me to bring myself to sit down and be like, “I’m going to stay in this one place and watch this thing for like fucking two and a half hours." But I’d say I’ve seen all of Tarantino’s films and he’s probably my favourite director. I like Wes Anderson’s colour palettes, and how with any scene you look at, any shot you look at, you can tell it’s one of his films. Nollywood is a huge influence for me – I just love how they didn’t have the most amount of money, or the highest production values, but they just get a camera and fuckin’ do it. They shoot what they need to shoot and they try to get the narrative out. I feel like that sort of quite unrelenting mentality, is what I have quite a lot of. I’m not going to wait to get money from a record deal or to get money from fucking anyone to shoot what I wanna shoot. I’m going to do research online, call people, figure it out, and fucking do it. No video I’ve ever released has cost more than £50. The entire production. None of them.

Do you think DIY is always going to be a part of your art?

DH: Well what does that mean to you?

What does DIY mean to me? Oh god, you’re interviewing me…

DH: I mean like, in what context?

So, for example, thinking of someone like Twigs, as she’s gotten bigger and she’s getting funding from brands to, say, create certain things, she still gets creative control obviously, but at the same time we know that what she is doing is still a branded thing. So how important is that sense of independence for you? You were talking about getting funding from places versus just being able to do it yourself.

DH: I’ve had this conversation with friends of mine and the conversation comes down to, ‘What does punk mean to the individual? What does DIY mean to the individual? What does independence mean?’ For me, the most important thing is to allow my message and my ethos to reach the biggest amount of people possible. So the way I see it is like this: let’s say that a big corporation contacted me, and gave me the means to self-direct an advert, whether it’s obviously for them or to just encompass their brand within my work. If I was to say no – though I still have my personal values, which is fine as well – that opportunity would just go to someone else. So if the opportunity was right, yeah I would take it – I’m not gonna be here forever, and I only have a window in which I can say what it is I wanna say, and do what it is I wanna do.

And what is that message you want to bring?

DH: I don’t think it can be intellectualised. As soon as I put my art in the world, it’s no longer mine and the meaning is totally malleable. You could tell me something about my art that I perhaps didn’t initially intend or initially even consider, but you may understand what I do better than I do. But I’d say artistic integrity would be the crux of any answer [about my message] I would give you; artistic integrity and to listen to your gut. [When you are creating art] you need to listen to your gut and to try and display the mental discipline to not allow external opinions influence what you think. You need to try and unlearn a lot of things and to just create from your inner voice, because that’s, I feel, who you really are. That’s what I try and do, as well as flirting with things such as wit and humour, in order to be subversive, to be controversial. But I feel as though at the crux of what I do is I always have to be true. And I feel like that’s why people fuck with me, ‘cos people aren’t stupid, they can tell when someone is being performative, when someone’s not being genuine. I feel as though, when people come into contact with my work – whether it’s my music or my visual work – whether they like it or not, they know that this person means what they’re doing, and that’s important.

Musically, there are more obvious references which would be like Tyler – Odd Future in general maybe – but there’s also stuff that references unencumbered kind of rock and hardcore and skate-punk – do you have influences in those areas?

DH: Trash Talk were a big influence for me. I don’t actually like a lot of music that I come across, in general – usually it’s one song on a particular record or three songs by one band throughout their whole catalogue that I really like. I wouldn’t say I was a fan of most music because I don’t fuck with most things that I come across.

One of my favourite songwriters is Trish Keenan from Broadcast, and I love the way they mixed their music so I’ll cite them as a big influence on my mixing techniques. Then when it comes to the drum programming, it can be J Dilla I have in mind, it can be Marilyn Manson’s digital stuff I have in mind, or even Mechanical Animals or some shit.

You were talking about being subversive – and one thing that I noticed with your visuals is you’re sometimes in makeup, or in drag. Particularly in the more, heavy side of rap that you’re making, it feels especially subversive to have you in a dress or something, right? Is that intentional, or is that just you?

DH: Um – both, both yeah. I mean, I both feel and I understand that, as a young black man who has a voice and a platform, it’s important for me to represent the alternative narrative, or an alternative archetype, because obviously no one group of people are homogenous. I feel as though it’s not even just young black males but black people in general – I don’t feel as though the spectrum of what this means is represented very well. I feel as though there’s so much emphasis on different typecasts, and it’s a bit embarrassing and uncomfortable for me.

I guess stereotyping is not the right word maybe, but there are certainly specific perceptions of what blackness is, right? To an extent you have it with like all people of colour – these concepts of what you’re meant to be like, and you either are that or you’re “white”, basically. And it’s not healthy or helpful to talk in those terms.

DH: No, it’s not at all, and to answer your earlier question – of course it’s who I am. This is an aspect of my personality and it’s definitely an aspect of how I feel it is necessary to express myself. But that aside, it is important because I have three nieces, and while growing up, they need visible people to look at and feel that they represent them. And not even just my three nieces, but young people, old people, whoever. Because, as I said, we’re not homogenous, and we’re not all the same. For me, growing up, there were only André 3000, Pharrell Williams, Fonzworth Bentley, of course Prince, Michael Jackson. And out of them, there were only the first three that I mentioned – as black male figures that I saw in the public eye – where I was like, “Wow, you’re different.” It seemed as if everyone else were like birds of a feather. Now that I am at this age, and that I thankfully have the visibility to try and contribute my voice towards that conversation, that’s what I’ll continue to do.

Also I feel as though, when I’m thinking about black people who make rap and hip hop music, this seems to be the only genre in which delinquent topics are praised and encouraged by these major record labels and corporations, you know? I don’t like it. Some of the biggest songs in the Billboard charts made by black people are talking about selling drugs, talking about killing people for fuck all, talking about killing people for really juvenile reasons, whereas you wouldn’t really hear that attitude being encouraged from a white female singer for example. And that’s another conversation; it’s something that’s quite sociopolitical. It’s bullshit man.

I guess there is this weird culture of kind of not talking about things like, say, misogyny in hip hop or almost accepting it as normal.

DH: Yeah, yeah. It’s definitely been normalised. Sometimes trap music will be playing, and – don’t get me wrong, I like some trap – I listen to the lyrics and I am like, “Yo, what the fuck?” It feels like I’m in an episode of Black Mirror. Am I literally the only person left that can hear the lyrics and understand the meaning of these words or what? It is what it is. I can’t stop anything – but what I can do is create a space for people who would either permanently or occasionally prefer an alternative.

In one of the interviews that I read with you, the writer specifically drew attention to how you were quite closed off. I read whatever interviews there were with you that are out there and didn’t find much out about you from them at all. So then I just sat and watched all your videos and listened to all your songs last night and you actually do put a lot of yourself out there. Even if you haven’t been saying it in an interview, it feels like it’s because it’s already out there in what you do.

DH: Bingo, bingo, that’s literally it. It’s like when you go to gigs and see people in the front row looking at their screen instead of at the person on stage. Like, what the fuck is wrong with you? That shit is right there. In my career I know I will do a number of interviews but [my work]? That’s the deepest of shit, if anyone really wants to know some shit, that’s where it’s at.

Does it ever scare you, that vulnerability – putting that much of yourself out there?

DH: No way. No way. I don’t understand why it’d be scary. I’ve had people in my immediate family be murdered, close friends murdered, so I feel like my perspective on life isn’t like other people’s. I understand this is part of a raindrop, man. I understand how fragile everything is. I understand the fact that literally every single thing, this interview, my career, everything, is literally based on perspective, everything is subjective, and there’s nothing that is inarguably objective. So, I’m here man.

Baphomet James is out now on Set Count Worldwide