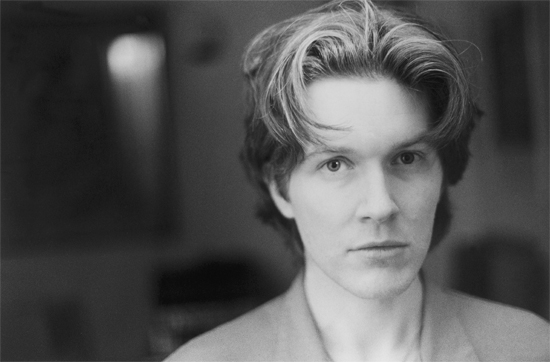

David Sylvian, who was once considered "the most beautiful man in pop" – let’s get the cliché out of the way – has just pulled his car over on the side of a road somewhere between New England and Brooklyn. It’s a late winter morning on the East Coast of the USA, and I imagine him cradling his phone off the freeway in a grubby layby, or perhaps in the grey parking lot of an anonymous shopping mall as a limp mist rolls in off the coast.

When I listen to his records, I picture something rather different: an elegant gentleman lounging on a red velvet sofa with a leather bound book pulled from the shelves of his library laying open on an antique table beside him, or, maybe, an intense, pale individual prowling around a moodily lit studio, poring over lyrics and questioning the purity of the sounds being put down on tape behind him. Instead, in my mind’s eye this time, pick-ups and SUVs shake his vehicle as they thunder past on a potholed road whose hard shoulders are decorated with bottles of cloudy yellow liquid tossed out of windows by tardy truckers. It’s not at all what I expected when he called.

Making assumptions about David Sylvian has always been ill advised. Japan, after all, started out as a glam rock band until Sylvian began to employ the richer, deeper voice that soon became his trademark. He fought hard against associations with the androgynous, extravagant New Romantic fashions of the 1980s, even though he had helped popularise them, and then established himself as a performer in his own right with the release of singles that included the haunting ‘Forbidden Colours’ – a collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto that was used as the main theme for 1983’s David Bowie starring film, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence – and 1985’s Top Five album, Brilliant Trees.

Before long he had stepped sideways into a murkier but intriguingly experimental world of ambient soundscapes, instrumentals and collaborations with the likes of Robert Fripp and Holger Czukay that, by rights, were never the realm of pop stars and yet to which he would frequently return.

Against everyone’s expectations, he also reconvened the members of Japan (save Rob Dean) for another round in 1991, this time under the name Rain Tree Crow, and, in 2005, he teamed up once more with his brother, Japan’s Steve Jansen, and roped in German electronic producer Burnt Friedman to record under the name Nine Horses, releasing an album (Snow Borne Sorrow) and a six track EP (Money For All) that also feature reclusive Swedish singer Stina Nordenstam’s last two recordings to date.

Perhaps the most surprising of all his moves – for a musician as quintessentially English as Neil Tennant, Morrissey and Jarvis Cocker – is the one that took Sylvian from the country’s shores in the early 1990s. He did it for love, which is the only logical explanation for a singer who, like an actor in a Noel Coward production, delivers his lines in such a well spoken, carefully pronounced fashion. Now 54, for the last 18 years or so he’s made his home in various places across the USA, from East coast to West coast via Middle America. It seems that David Sylvian doesn’t like to be tied down, and the same could be said of his work.

"Once one moves away from home," he tells me as we manoeuvre ourselves into interview mode, "you become something of a nomad: you’re not really rooted anywhere and there’s a sort of liberation in that. You can feel free enough to keep moving round the globe and live temporarily in any location and feel quite comfortable. The downside is you’re not rooted, and a lot of people need to feel rooted in a location to feel grounded in life. But I’m not one of those people."

Despite the fact that Sylvian’s work has followed what could equally be referred to as a "scenic route", it’s odd to spend time looking back over the career of a man who makes it clear he prefers forward motion.

"To even use the word ‘career’ in connection to what it is I’ve been doing all these years seems strangely odd," he muses. "I’ve just been pursuing personal goals and dealing with personal issues that surface in the work."

It turns out, however, that Sylvian has learned to make the best of these moments of retrospection. He has, after all, spent much of his life exploring "different belief systems", as he puts it, embracing, amongst other things, aspects of Hinduism and Buddhism. A calm, rational air is therefore very much at the heart of the way he presents himself.

"I believe there are certain aspects of life," he explains, "that one has to go through. It’s one’s purpose to be here to experience these things. You could call them lessons in life from which you have to grasp the seriousness to enable you to move onwards."

In fact, he later confesses, he nearly gave up on music altogether in the late ’90s as he struggled to complete work on his final album for Virgin, Dead Bees On A Cake. It was only the advice of his spiritual guides that encouraged him to continue.

"I actually asked two of the teachers I was with during that period whether it was time to stop, and (they) said, ‘No, it’s not time to stop, you have to continue working in music.’ So I just went back to it and finally managed to wrap it up."

More than a dozen years later, Sylvian is still recording and performing (though his proposed spring tour has been cancelled due to a back injury), and this is celebrated by the release of A Victim Of Stars 1982-2012, the first compilation of his solo work to take in releases for both Virgin Records and his own label, Samadhi Sound. It’s a collection that spans an astonishing thirty years and, in a typically Sylvian-esque flourish, the title – taken from a track recorded with French producer and composer Hector Zazou for his album Sahara Blue – was inspired by poet Arthur Rimbaud, the centenary of whose death their collaboration celebrated. Sylvian, like Rimbaud – who travelled for much of his short life – is clearly a restless soul, but, unlike the ‘infant Shakespeare”s poetry, Sylvian’s creativity shows no signs of drying up prematurely: the last three decades have given us a succession of rich, ornate pieces, portraying an individual unafraid of accusations of over-sincerity and intent on proving that his chosen musical form can be erudite and articulate.

Straddling the divide between pop and art, A Victim Of Stars swerves from the Oriental-tinged, stuttering synth-pop of his debut solo single, ‘Bamboo Houses’ – like ‘Forbidden Colours’, recorded with Ryuichi Sakamoto – to the almost funky swagger of ‘Red Guitar’, on to the lush, swooning ‘Taking The Veil’ and the almost pre-Raphaelite sensibilities of ‘Orpheus’. The somewhat ironically named ‘Pop Song’ sees him tease its melody out while random, jazz-inflected embellishments are scattered over a minimal beat – not unlike Talk Talk’s early experimentations on The Colour Of Spring – and ‘I Surrender’ is a sophisticated, lengthy excursion into the kind of late night, softly lit romance which The Blue Nile specialised in, something that might prove a little too earnest for those who missed it first time, but which still boasts an enviable truth and beauty absent from much of the music aimed at today’s adult market.

Evidence of his more unconventional work from the early part of his career is sadly absent, but the inclusion of tracks from both Blemish (the shifting shapes of ‘Fire In The Forest’, for example, or the sparse, dreamlike ‘The Only Daughter’) and Manafon (the evocative ‘Snow White In Appalachia’) prove that orthodox structures rarely restrain him, as do tracks from Manafon‘s companion album, Died In The Wool, which offered variations on the album constructed by the likes of Pierre Boulez protégé, Dai Fujikura, and Christian Fennesz. Nonetheless, his work on the underrated Nine Horses project confirmed that he’d lost none of his ear for melody, with that characteristic baritone beautifully framed amid the jazzy, luxuriant melodrama of ‘Wonderful World’, while the obligatory new track, ‘Where’s Your Gravity’, could – in all honesty – have been recorded any time in the last 25 years. This, when it comes to David Sylvian, is what we call ‘a good thing’.

It’s not the first time he’s seen his work repackaged and remarketed – over the years there have been five separate compilations of different constellations released – but the previous occasions seem to have helped him come to terms with the past.

"It’s hard looking back," he admits quietly of previous campaigns. "It’s not something I enjoy doing. And I initially thought it was detrimental to the production of new work. But ultimately it didn’t prove to be the case because it really spurred me on to move away from what I’d done in the past. The current compilation I really had very little to do with. It’s not of my instigation. It was initially going to be just a compilation of work released on Virgin over the 21 years I was with them, and it evolved over time through conversations between my management and EMI into its current form. I’ve got to be honest, I don’t even know what the running order or track listing is."

He laughs at the absurdity of this situation, but there’s no bitterness evident.

"I was very happy that they embraced the Samadhi Sound releases in the packaging," he continues. "Without the more recent work it’s really only part of the story and it’s not even, to me, the essential part. Everything that I’ve done to date since I left the Virgin label means so much more to me than what I did while I was with them."

It’s not hard to understand why an artist of some four decades standing might see the recordings they’ve overseen independently – from conception to delivery into the marketplace – as being their most personally significant. He is, however, at pains to emphasise that his relationship with his former label was healthy.

"Virgin were very welcoming of my departures from the major solo releases and vocal records, and that was basically due to Simon Draper, who was running the label at that time," he clarifies. "He trusted me. He allowed me an enormous amount of freedom that wasn’t in my contract, to be honest, in terms of which musical direction I wanted to take. And when he left the label he made sure that the freedoms he’d given me were written into my contract, so that was an enormously generous gesture on his part."

Sylvian’s entire career has been one long series of fascinating curveballs delivered in a sophisticated, unusually refined style, and it serves him well on A Victim Of Stars to see the manner in which he’s continued to develop and explore new ideas. It’s been confusing for fans, of course: he flip-flops from his more structured songwriting to improvised excursions with regularity, adopting different styles for which less stubborn individuals might hide behind pseudonyms. But that would be disloyal to his muse, it seems.

"There’s no desire to alienate," he argues. "If the work doesn’t communicate itself successfully then it’s really a failure, in my opinion. But the flipside of that is that you have to be true to the work itself, and some avenues you choose to walk down are just not going to be accessible for everyone, and I accept that. So if I’m working on a piece that is largely experimental and has very little familiar form to it, I know it’s going to alienate a certain number of listeners. I’ve been doing this for a long time now, and the trick is to stay totally engrossed in what it is you’re producing so that you follow your instincts. And sometimes that means you take a road that’s slightly less travelled musically. I wouldn’t want to dilute the work for the sake of making it accessible, because basically you’re making the work weaker by diluting it, and you probably won’t reach that many more people anyway. You can’t second-guess an audience, and I think that’s also underestimating the intelligence of your audience, and you might as well just go for it 100% and hope for the best."

Underestimating his audience is one thing of which few can accuse Sylvian. Whether it’s been the romantic sweep of 1987’s Secrets Of The Beehive – where titles like ‘Promise (The Cult Of Eurydice)’ and ‘When Poets Dreamed Of Angels’ hint at the fanciful content within – or the prog-rock influenced results of his initial partnership with Robert Fripp, The First Day, (represented on A Victim Of Stars by ‘Jean the Birdman’), he’s always issued new challenges, testing out fresh ground, unconcerned as to whether his audience will follow. It’s been even more evident on records like Plight And Premonition, his first, 1988 collaboration with Can’s Holger Czukay – "I just sat down and started playing, I think it was a harmonium, an old pump organ, and unbeknownst to me Holger started to record what it was I was doing and feeding me tape loops as I was playing" – or When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima (2007), a single, 70 minute instrumental to accompany a Japanese art installation which, according to his website, "isn’t really complete until the sounds of the town Honmura are incorporated into the listening experience".

It’s clear, in other words, that David Sylvian has rarely done what one expects. What he does, however, he does very seriously indeed, with particular emphasis throughout our conversation on the words ‘art’ and ‘artist’. In fact, he chooses all his words carefully, expressing himself with a rare eloquence and attention to grammar that suggests not only a good education and a fondness for literature but also a refusal to dumb down. At times his vocabulary is almost archaic, but these qualities reflect the lyrical content of his work, which has rarely been less than solemn. Surprisingly, given that he’s always appeared so fastidious, he puts this down these days to his age, but suggests that, in his writing, he rarely struggled for long to articulate his thoughts.

"I can’t labour over the lyric writing," he says, "because it would become too false and self-conscious, and that’s just not the way I write. I tend to complete the lyric in one sitting. Because going back to when I was a younger man, if I didn’t do that, I found myself searching for those lost lines endlessly, for months afterwards, and I just hated that process of searching, so I would always complete the lyric in one sitting if it was possible. And most times it was."

Running his own label has afforded him even greater freedom. Samadhi Sound was set up to release his 2003 album, Blemish, but it has also provided a home for work by David Toop, Akira Rabelais and one of the godfathers of modern day ambient music, Harold Budd, whose double album Avalon Sutra / As Long as I Can Hold My Breath, was released in 2005. Most importantly, though, it’s meant that his creative process is now answerable to no one but himself.

"Sitting down to write the lyrics these days, it’s more a matter of just tapping into the moment and being true to that, and allowing the work to flow at that moment in time, because the process I work with now is more like automatic writing. I write the melody and the lyrics simultaneously and record it immediately thereafter so the lyric is complete, which all takes place in a matter of hours from sitting down to write the first line to completing the vocals for the record, so there’s not a meditation on the content of the lyric. In fact, quite the reverse. The lyric tends to surprise the writer to some extent. I’m not always aware of what it is I am writing about or how revealing it can potentially be. And that’s what’s exciting about it, to be honest. That’s really the thrill of the process. And keeping it as fresh and alive as possible, and likewise recording the vocal so close to the period in time in which the lyric was written, means that there’s a freshness there too. There’s not enough time for too much reflection."

News of one of his forthcoming projects, a collaboration with Jan Bang and Erik Honoré, underlines this: "I recently did some readings of some poetry for a gallery installation in Norway, and they’ve turned the readings into a full blown album. I just heard that for the first time two days ago, and I thought what they’ve produced was incredibly beautiful, as is everything they touch. I mean, they have a wonderful notion of composition and all the rest of it, and I love what they’ve produced, so that should see the light of day relatively soon."

It’s actually when he talks about the future that he sounds most invigorated, as when he mentions the album of duets with Joan As Policewoman on which he’s spent the winter working.

"It’s been a return to more traditional forms of songwriting, and there’s been a complete joy in that process. I love Joan. She’s an absolute pleasure to work with."

Preparations for a new solo album are also underway, it turns out. "I’m gathering material now through May," he confides, "and I’ll begin work on a new album relatively soon."

In addition, there’s a DVD release due of Amplified Gesture (the documentary that Sylvian and his manager, Adrian Molloy, produced about improvisation. (All four releases will appear on Samadhi Sound.)

Back when he first started writing, the idea of people still making ‘pop’ music as they approached their 60s was completely alien, but slowing down, or even retiring, do not appear on Sylvian’s agenda.

"In some senses it’s surprising," he admits, "because I frequently thought of walking away from it. And maybe it’s that sense of liberty that I can walk away from it that allows me to keep working and finding new avenues to explore. As long as there’s something to hold my interest I’ll keep plugging away. I’m not sure that artists feel they have that liberty. You don’t see a great deal of evolution in the lives of pop artists, or rock artists for that matter. I think it’s not possible to allow artists to evolve over a period of time, to mature and produce different kinds of work. But I wish more artists would take that liberty just to see where it would leave them and if their audiences would follow. If more people talked that way, I think you’d have a greater variety of music to choose from."

It’s now midday on the Eastern Seaboard, and David Sylvian has other matters to which to attend. The grimy environs in which I’d envisioned him an hour ago have long been dismissed from my mind, and I picture him at last pulling on smart calf skin driving gloves, adjusting his cravat and firing up the engine of a vintage imported car to continue his journey. He winds down the window as the car slides out of its parking space, resting an elbow nonchalantly on the doorframe, then pauses a moment at the entrance to the main road to consider his route. A weird drone drifts from the car: it could be the engine, it could be the music to which he’s listening. And then, instinctively, he chooses the road least travelled. It might take longer, but the scenery is second to none…