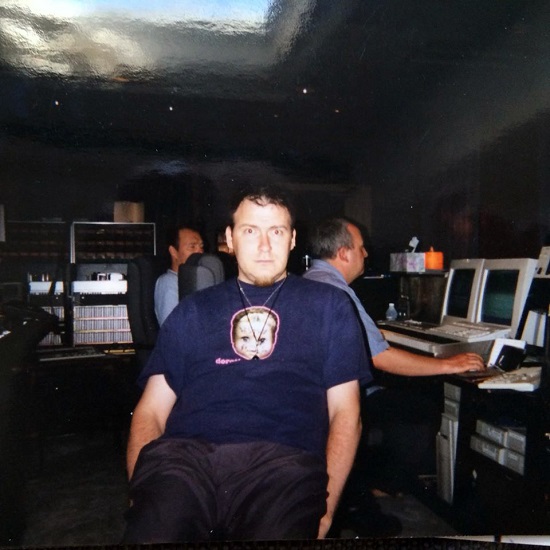

Danny Hyde, John Balance and Peter Christopherson in New Orleans, picture courtesy of Drew McDowall

Feature contains NSFW video imagery

Four years in the making and almost twenty years in the wilderness, Coil’s follow-up to the masterful studio experiments of Love’s Secret Domain, was finally released by Cold Spring in October 2015. Backwards‘ final mix was concluded in Trent Reznor’s studios in New Orleans in 1996, but issues with "grey men" are said to have prevented it from emerging to a keenly anticipating audience. Evidence of its majesty subsequently slipped out in 2001 on a pair of Russian compilations where the hyperactive techno of ‘AYOR’ and the astonishingly affecting elegy ‘A Cold Cell’ presented the stylistic extremes that Backwards travels between – from the delerious and convoluted sampladelic experiments of the nineties to their minimal moon music of the next decade.

While the majority of its tracks were heavily redeveloped following Coil co-founder John Balance’s untimely passing in 2004 for their final two albums, The Ape Of Naples and The New Backwards, the original aural intentions for the release are only now evident and in many cases vary dramatically from the newer versions.

Danny Hyde, Coil’s co-producer and programmer since their early days right up to and including Backwards, helped instigate the recent release following last year’s equally welcomed set of Coil’s remixes for Nine Inch Nails, also released by Cold Spring as Recoiled (and becoming this site’s reissue of the year in 2014). Extensive experience of engineering and producing in some of the largest of London’s studios throughout the eighties lent him unique insights into the evolving technology of the time as it travelled through analogue to digital with the rise of the sampler in between. His ensuing experiments went on to help forge some of Coil’s signature sounds of the time, from the stuttering wayward loop modes of ‘Elves’ to the Eastern hues found on tracks like ‘Nasa Arab’.

But Backwards would be his last album with the band for several years; his frustrations with its lack of release led him to almost give up his career in the music business. He started working again with Coil’s Peter Christopherson in 2002 and went on to help shape The Ape Of Naples and The New Backwards as well as music by Christopherson’s Threshold Houseboys Choir. Meanwhile he emerged from behind the mixing desk to start projects of his own as Aural Rage for solo outputs, and Electric Sewer Age, his planned series of anonymous collaborations.

On the occasion of Backwards much delayed release we chatted with Mr Hyde about its long and erratic evolution, along with encouraging him to reminisce on his work with Peter Christopherson and John Balance over the years and how that continues to inform his post-Coil compositions.

You started you career at The Point Studios – I was having a look at some of the records that came out of there in the early eighties that you worked on, and I’m guessing Dave Ball [of Soft Cell]’s In Strict Tempo LP, featuring people like Gavin Friday and Genesis P-Orridge, may have been your entry point to the circle of artists that included Peter Christopherson and John Balance?

Danny Hyde: Yeah, I remember those sessions but I don’t remember Genesis going to them. We did an early version of a Soft Cell album at The Point Studios which went on to be changed. Then Dave came in on his own and did his thing. People like The The would come in. It was more the Some Bizarre circle who were there, Coil never actually came in themselves.

It was a complete coincidence when I met Coil at Paradise Studios because they lived ‘round the corner. And then from meeting Coil I met Genesis and Psychic TV as well.

I’ll tell you a funny story as an aside, when we were doing those early Coil sessions Peter wanted somebody who was on the BBC to do a vocal part, I can’t remember his name [Most likely Paul Vaughan, narrator of BBC science documentaries such as Horizon, who appears on ‘The Golden Section’ off Coil’s 1986 album, Horse Rotovator, Ed]. Peter, in all seriousness, phoned up the BBC and said he needed someone from a programme called The Real World, he said, “Can I speak to so-and-so from The Real World? I’m calling from Paradise.” And we just cracked up, I’ll always remember that, it was just classic Peter. He didn’t mean it, it just came out like that, it was brilliant.

What was it about Paradise Studios that meant Coil chose it for their second album?

DH: Paradise Studios was the most fully computerised studio in Europe at the time, we had Fairlights [early digital sampling synth], we had WaveTerms [sampling computer module], we had every digital keyboard you can name under the sun, plus, crucially, it was about a quarter of a mile from their house [laughs]. So I think they booked it on spec and just really liked it, but they had actually bumbled into the perfect studio without even realising it.

So you would have witnessed first hand analog evolving into digital gear?

DH: Oh yeah, we were using analog tape at the time; of course you could hook up a Fairlight and run it in sync with the multitrack but there was no post editing, it was the old days of drop in, drop in, drop in. If someone did a vocal, you didn’t record it then edit it digitally and then lay it on the track, you’d have to do it manually – they’d sing along and you’d have to drop them in. And if you messed up, well that was gone forever.

I always liked analog and I bought a Korg Polysix very early on, which is on most of the Coil records I worked on and I still have it. I loved it.

But around this time you also seemed to embrace the sampler as an instrument.

DH: I loved samplers, I just couldn’t afford them. When Paradise moved to the Fairlight 3 it was 70 grand! [But] I did this Bucks Fizz session, believe it or not, with this producer called Nick Tauber. It was pretty rubbish and their management wouldn’t pay us so Tauber said to me, “I’m really sorry I got you involved in this, I’ll make it up to you. I know this top bod at Akai, why don’t you speak to him and you can get everything at trade price early." It just so happened that the Akai samplers were coming into the country and so I think I got number two in the UK! And I got it at a really good price and then I was off and running ‘cause the next minute suddenly dance music happened, so you’re whizzing all over the place doing sessions.

What was your first encounter with what went on to become known as electronic dance music?

DH: It was probably at Point, a guy called Frankie ‘Bones’ and Tommy Musto [AKA Flowmasters], they came in from New York to do some tracks. [They] entered the studio and they were buzzing and having a laugh and I had a sampler and they just spun some records, we sampled them up and I strung some loops together and off we went.

A guy called Ben Chapman saw me doing ‘Let It Take Control’, he liked it and said, “Come and do some sessions with me”, so we did Adamski and we did Blur and we did bloody Jesus Jones and it was a whole shebang of things.

So not long after then you worked with Coil to develop Love’s Secret Domain?

DH: From Horse Rotorvator we were always working on stuff at a place called Milo Studio in Hoxton; we were building up towards Love’s Secret Domain and then the sampler came along. Coil used to do things in spits and starts – you’d do a bunch of sessions and then you wouldn’t hear anything for six months and then you’d do a whole load more and so on. Then they’d book a final studio because they obviously realised that if they didn’t book a final studio it’d never get finished and when they booked Matrix [Studios] to complete Love’s Secret Domain I was full-on with these samplers so they got used.

At what point were you aware you were working on what would becomeBackwards – I understand it was started in 1992?

DH: Well ‘93 we were in Swanyard [Studios] and it was taking shape to be the next album. The actual track ‘Backwards’ was done in ’92 with Tim Simenon, he was a mate of theirs and he had some drum loops and we created the track in about half an hour, and then that surfaced again in Swanyard and Geff [John Balance] added some vocals for it. [But] it wasn’t until ‘96 we actually went to New Orleans, when again, it was a case of ‘get a studio and then we have to finish’.

In between ‘92 and ‘96 Coil also seemed to enter a remix phase including remixes for Depeche Mode and also their first work with Nine Inch Nails.

DH: The first Nine Inch Nails sessions were ’92. ‘Gave Up’ for Depeche Mode was in ’93, and ‘94 was [remixing Nine Inch Nail’s] ‘Closer’ and ‘The Downward Spiral’, so in a way you’re right, but it was spread from ‘92 to ‘94. ‘95 we were more involved in Black Light District.

Do you think this ‘remix as an artform’ sensibility actually made it difficult to regard anything as finished?

DH: Well that’s quite a good point but Coil were like that before we got into the remix phase. After Horse Rotorvator we did a bunch of songs which have not actually surfaced, they’ve disappeared into the vault somewhere. I remember doing a song called ‘Smelly Tongues’, I remember the beat and everything, but I haven’t heard it since.

My memory of Backwards [not getting released], is purely linked to the grey men. Now I know Geff later on would have probably not released it in the form we’ve released it now because he’d moved on, y’know, but Backwards at the time was not released because of the Americans essentially. By the time we’d hit Backwards I sat with Pete and I said, “Look, I’m ending up writing a lot of these songs with you and I’m entitled to publishing,” and he said, “Okay, fair enough." So I’d done this publishing deal and I came back [from New Orleans] and my publisher said, “I’ve got this money for you, but I need to know the release date before I release the money.” I said, “I should know in six months.” But then it went on and on and on. I had to pressure Pete to find out what the hell was going on because it was causing me problems. Unfortunately I’d borrowed some money from my mother-in-law who then got cancer and died within six months and I couldn’t pay her back because I was waiting for this money. So I was getting really fraught with this whole thing and I said, “When’s this album coming out? The publisher’s not releasing the money to me ‘til it comes out." And it was, “Oh, it’s going to be soon, it’s going to be soon.” And then it was like, “No, it doesn’t look like it’s going to happen." I pretty much got the impression that Interscope – Pete was a video director for them – were trying to pin him down to say, “You can only make videos for us” as part of the contract to release Backwards, but the suggestion was there were some things in the contract that Pete and Geff just didn’t want to sign and that’s why it didn’t get released.

And then as time went on, as we got closer to when Geff died in 2004, I know by then he thought Backwards was a bit too dancey ’cause he’d done Musick to Play In the Dark and then they were definitely getting a solid sound as opposed to flitting through different styles. But, like I say to everybody, don’t judge Backwards as the best of Coil – it’s probably not – but what it most definitely is is the stepping stone between Love’s Secret Domain and the Musick To Play In The Dark series, it’s part of that history, it is what it is…

So I was really pissed off obviously… when Backwards didn’t come out, not with the Coil boys ‘cause it wasn’t because of them, but with the business. In ‘98 I left the business, I was just so disgusted with the whole process that I kind of retired for four years.

When I heard the newly releasedBackwards I was surprised because I hadn’t heard a lot of it before but I had thought I had. And that’s because there’s the demo tape you did that’s freely available online, but I’m guessing that’s the pre-New Orleans tracks…

DH: That’s correct, yeah.

And then, more recently you worked with Peter Christopherson on The Ape Of Naples andThe New Backwards (all of which feature re-worked songs from the Backwards sessions), but this latest release sounds different – it sounds great! It made me wonder what was significant about the New Orleans studio that transformed that demo so much, and why did you rework the tracks chosen for The Ape Of Naples, andThe New Backwards, as opposed to releasing what you’ve just done now?

DH: Peter, being the most decent guy in the world, I think he was aware that if he released Backwards as it was as he’d not signed the contract there would be trouble. And Pete was a very honorable man, a lot more so than me. He probably didn’t want to get Trent [Reznor, whose label, Nothing Records, an imprint of Interscope, was set to release the LP] into any crap ‘cause he probably didn’t know the tie-up was there – that’s my view on that. By the time we’d done The New Backwards we were re-working the songs to be so radically different that they could be construed as new songs if it ever came to court. Not that it would, there was no real problem there.

What was it about these tracks you’d made over a decade ago that meant you were both still interested in working on them?

DH: Well, the obvious link is that was the last of Geff that we had. We did write new things for the Threshold Houseboys Choir; to be Coil we couldn’t just get in some guy to do vocals, we had to use the Geff tracks, but we never really talked about how we felt about the tracks. But, me personally, I love the New Orleans sessions. I thought there was a magic in the air, just being somewhere different away from a London studio, we were fired up and we seemed to get loads of work done in two weeks and we really enjoyed it. Geff, bless him, could be quite hard in the studios if he wasn’t on form, but in New Orleans he was on great form, he was sparkling, so I really regard the tracks with fondness.

‘Cold Cell’ is probably one of my favourite Coil tracks, it takes me back. At the end of the song there’s [a recording of] a tram in New Orleans running on squeaky wheels. I can picture Geff there singing it and it sends shivers down my spine. It was actually created in about half a day. I think Geff came up with the bass line and then I did all the chords and then Pete had a recording of the trams that he wanted to put on there. Then Geff just sang and it was done. It was really fast which was great because some tracks with Coil could take three years.

Geff had gone off and done loads of vocal lessons, I don’t know why, and by the time he got to New Orleans and got in front of the mic, he was a totally different person. He just had control of his voice in a totally different way, and once he realised that it totally worked, like on ‘Cold Cell’, they then went into Musick To Play In The Dark with a different attitude. There was a lot more confidence in the idea of, “I’ll just have my voice and a simple arrangement."

Listening anew to Backwards and to other recordings from the time they seem to bear dub techniques – the studio has been used as an instrument.

DH: Dub influence, yeah, you can’t fail to have spent any time in a studio and not be impressed by Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and all those guys messing around with echoes and things. We messed around with samplers. I think [Coil] enjoyed it if I twisted things up – if I didn’t twist things up maybe I thought I wasn’t working, I’m not sure. Eventide samplers bouncing things around and you’re swinging the wheel and turning and switching things, just recording what you do, and you can never do the same thing again because you don’t really quite know what you did.

Peter gave you a freedom that I have never, ever had from anybody else in the studio. He would appreciate anything that anybody would do as long as they were putting their heart into it, so that gave you the opportunity to try things out, to go off to the left or the right and if it didn’t work, it didn’t work. With all other bands you wouldn’t do that because you’d be conscious they were paying for studio time and they wouldn’t be happy with detours.

You also brought in Middle Eastern stylings, particularly on ‘Nasa Arab’, what got you interested in Arabic music?

DH: Funnily enough I named that track after a racehorse. I said, “Let’s call this Nasa El Arab”, but Geff said Nasa Arab sounded better. There was Mongolian throat singing on that track. Again [it was] an experiment – I got the MPC60 running a 6/8, 7/8 two-bar loop so everything you played into it would come back at you at a time you weren’t expecting. It would start looping and you’d play a bass line or whatever and it would be back at you before your programmed 4/4 brain [expected] and so it created the rhythm, it was not a pre-planned thing.

I did an album with a guy called Cheb Khaled who was an Algerian raï singer [in 1988] and I was so impressed by that guy – he’d play the keyboards in these mad time signatures while singing. His technique stuck in my head but I could never emulate it live – I couldn’t play live like he did; I needed to create the time signature in my machine to artificially create the groove.

Some time after ‘retiring’ in 1998, you started working with Peter Christopherson again in 2002.

DH: I pretty much emailed Pete and begged him for a fresh chance. I was working in TV at the time and the money was really good and the hours were short but my love for what I’d done with the members of Coil was drawing me back in. So I said to Pete, “Look, I’m kinda bored is there anything going on?” and he said, “Yeah, come over." That was how we got reacquainted. Pete brought me up to speed and he said, “Well, let’s do a track." He’d got this new bit of kit called Ableton Live and we played with that and came up with ‘Unearthly Red’.

I’m very fond of ‘Unearthly Red’ – Coil used it in their live shows in 2002. Did you go along to any of the gigs?

DH: I did the live sound at the Barbican [in London, in April 2002].

‘Unearthly Red’ was used as the climax to that set. Would you have liked to have been more on the performance side or do you prefer being studio based?

DH: I don’t have the courage to go on stage. Since Aural Rage, and particularly since Electric Sewer Age, the amount of enquiries has been quite intense and I’ve always managed to find an excuse not to do it but when I’ve sat down I’ve thought, “You know what Dan, you’re missing out on a great experience, even if everybody booed you off and threw cans of beer at you, how many people can say they’ve done that?” So I’m starting to think that maybe I should just bite the bullet and try and put a show together because I think I’d like to do it. But, the other part of me thinks, “Who wants to see some fat, middle-aged geezer on stage?” I haven’t got the flamboyance of Coil and I prefer to sit like William Burroughs, in a suit, in an armchair and just play the things.

Your debut solo release, Nature Of Nonsense, that came out in 2005 as Aural Rage, brings out, or identifies, some of what you contributed to Coil’s sound throughout the 90s, you can hear some of those elements come through.

DH: Yeah, that lavish over-production [laughs]. And why stick one sample on when you can stick fifteen hundred. I admit, I’d love to get the album in a big studio and mix it properly. I’d mix it so much simpler now – I think that comes with confidence you know, later on you realise you don’t need fifteen hundred things when two things can do it.

The original idea behind your most recent project, Electric Sewer Age (ESA), is that of an anonymous collaboration – people would know the kind of circle of artists it’s coming from, but they wouldn’t know which combination of those artists would be involved. How did you come up with that approach?

DH: It’s a shame, the original idea [was from] a guy called John Deek, a great Coil fan who I met through Pete and became a great friend of mine. He was a complete nutcase, he was like the lawyer from Fear & Loathing…, he was such a character. I said I’d mention [the idea] to Pete ‘cause he would probably like that and he did, but [then], unfortunately, Pete died.

I had the Moon’s Milk record that we’d been doing [“new reinterpretations” by Hyde and Christopherson of Coil’s series of singles from 1998 for a projected expanded reissue in 2006] and it became quite apparent if we didn’t do something with that then it was going to end up on a Russian bootleg and that didn’t seem fair as I explained before about my previous history within the business. John [Deek] said, “Well let’s put out Moon’s Milk." I said, “Moon’s Milk is not an ESA record, it’s not the philosophy of what ESA was about." He said, “It doesn’t matter, if we don’t put it out this is going to happen, this is going to happen." So I met up with Ian [Johnstone, Balance’s partner at the time of his death] in London and explained this to him and he said, “Yeah okay, go for it, do it.” This was after Pete died and so we left it a year because it just seemed nonsense to do it too early, and that became the first ESA record. But it had gone completely against what we said ESA should be about because everyone knew it was by Peter Christopherson.

But ESA 2, [Bad White Corpuscle released in 2014] contained tracks we did in 2006 and I don’t need to say who was on there because there are other people.

But talk of the Electric Sewer Age philosophy leads me on to the Recoiled record [the “pre-big studio mixdowns” of Coil’s remixes of Nine Inch Nail’s tracks from 1992 and 1994, unreleased at the time]. Because of the way we worked I had all the files and every movement we did to every remix saved. I had every move we did on the keyboards, ‘cause the keyboards were mine, I had every setting, I had every sequence saved. I had every single part of what we did outside the big studio. Once we got in the big studio we synced all our machines in and off we ran and did these remixes, but the demos we did at my house and at Pete’s house. So when the Nine Inch Nails’ forum said to me, “Look, we’ve heard there’s these demos that were unreleased. Do you have them?” I hunted through my DAT collection and I found a few outtakes and thought, “I was a bloody idiot – I didn’t record those demos as I should have, but I’ve got all the files, I’ve got all the settings and I’ve got all the notes, I’m going to recreate them!”

So I recreated all the songs as I created them in the original case and I ran them through the mixing desk again, this was in 2012, and I listened to them back against the snippets of DAT that I did have from ‘92 and ’94, the original sessions, and I thought “I’ve matched that up bloody well." They [Nine Inch Nails’ forum] believed that these were the ‘92 and ‘94 originals, but using the Electric Sewer Age philosophy I thought, “If you don’t know it, let’s see how you judge it." And they liked them. A year later, Cold Spring said, "We’ve heard these demos on the Nine Inch Nails forum can we release them?” And I thought, "Well, why not?”

Backwards is not that sort of experiment, Backwards is the genuine thing from New Orleans.

So Recoiled was a kind of restoration, then? You had all these copious notes?

DH: Yeah, that’s it – my notes were about 500 pages thick of type in the days before computers when I’d did it on a Word Processor. I was bloody anal like you wouldn’t believe. I’d finish a session, particularly a Coil session, and I’d go home and type up all the notes so all the settings would be recorded. I was so pleased that they came in useful eventually. They were always kept in case there was a remix [and] someone said, “That track we did, I love it, can we do it again and change it slightly?” But, on the whole, the notes have never come in handy again because Coil, if they wanted to re-do a tune, they wanted to re-do it from scratch. But thankfully those hours and hours of typing came in handy for the Recoiled release, because [it was] as though we were back in ‘94 or ‘92 – I was really pleased that all the things came back as they should.

The future – can we expect more Aural Rage or other projects from you?

DH: I hope so. The person that put out ESA 2, Old Europa Café, he’s often asking when we going to do Electric Sewer Age 3. I’d really like to get on with the project. I love the studio. It’s still the place I’m most comfortable in, just sitting back and playing with sounds and feeling like I’m a kid in a toy shop again. There’s no feeling like it. My kids should probably shoot me for saying that, I should really say that the birth of my kids has been the greatest thing – and it was, but the next greatest thing is when you’re in the studio. Normally when you’re in the studio alone, it’s the middle of the night and something’s working then you just feel that you’re on a different level. That’s something that you can’t get from normal work. I need that, I’m addicted to that. It might be the time to start getting some people in to see where it leads and then kicking them the hell out and mangling the sounds when they’re gone.

You can keep up-to-date with Danny Hyde’s various projects over at AuralRage.com