The cover art to Flesh And Machine – the tenth solo album by the unassuming musician, renowned producer and ambient pioneer Daniel Lanois – contains a curious image: a baby with cybernetic antennae. The child represents Lanois himself, the part of him which is always looking for a sound that’s never been heard before. The artwork also represents creative rebirth as the LP – his third for ANTI-, has finally reconnected with the experimental roots he threw down as Brian Eno’s protégé in the early 1980s.

The quietly-spoken Canadian may well have been involved in popularising the ambient genre as well as playing, recording and producing music for four decades now while recording big – and no doubt expensive – records for U2 and Peter Gabriel and has been drafted in to help Bob Dylan and Neil Young reconnect with their creativity. But this record marks the first time he has truly deployed every sonic weapon in his arsenal and attempted to break virgin ground in support of his own music.

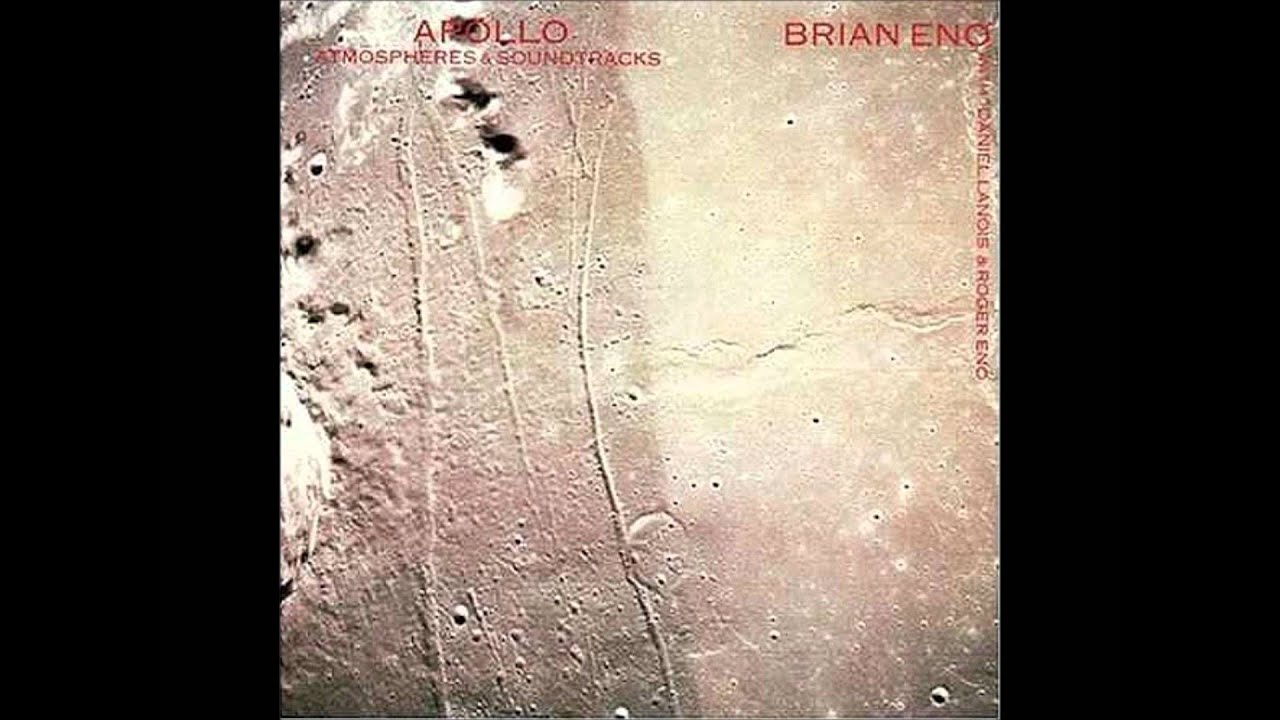

When Lanois talked to Andy Kaulkin, founder of the ANTI-label, about the album, it was initially conceived as an ambient work, and it’s true that tracks such as ‘Forest City’ take the classic Brian Eno albums that he worked on [Ambient 4: On Land from 1982 and Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks the following year] as a jumping-off point. His guitar is processed to the point where it is no longer possible to tell what the source instrument is, leaving in its place shimmering celestial drones that sparkle like glitter in the void. But mainly he is concerned with the future not the past. The album bristles with new ideas. He spent countless hours processing a very limited array of rock instruments – steel and electric guitars, piano, drums and human voice – to create a futuristic and near-infinite sound palette.

The stunning polyphony and cascades of ultra-pointillistic sound on standout album track ‘The End’ all come from two humble sources: guitar and drums which are then sampled, sliver by tiny sliver, processed and placed carefully back into the track. All of these countless samples, no matter how radically they are changed, have to be placed back into their surroundings in a harmonically correct manner, so his process is not only highly technical but compositionally very astute as well. His method is so dazzling in places that it sometimes sounds as if Burial, Amon Tobin, Prefuse 73 or Four Tet were producing a modern fusion LP or a desert rock album. However, with Lanois blissfully unaware of who these producers are, these effects were very much the product of a personal evolution, as he tells me:

Can you remember a point when you first became interested in music for its textural rather than melodic properties?

Daniel Lanois: I became interested in the processing of sound after many years of fairly standard recording procedure. I was a recording engineer in my own studio for the longest time. My brother and I were essentially offering a package that included vinyl cutting, sleeve art and recording. We offered the fundamentals so you could have your record mastered, you chose the artwork and have a thousand pieces of vinyl. That was the basis of what I did for a long time. We did a lot of gospel groups because I was associated with a Christian organisation in Canada. So we made hundreds of albums in a very conventional manner. Not a lot of processing or textural work, nothing outside of the usual expectations. That was pretty much my line of work for years. It was how I paid for my equipment.

Then I started working with some slightly more adventurous record producers out of Toronto, a guy by the name of Billy Bryans who was connected with the lesbian band scene so I was doing a lot of pretty far out work for the first time in the mid-70s. One of those adventurous projects was the Time Twins. And it was that record that Brian Eno heard. They went to New York and they played Brian Eno their demo and he really liked it. He said it was very adventurous and far out sonically. He asked who recorded it and that was the beginning of my work with him – that’s what drew Brian Eno to my studio. And he came into my world with some piano recordings that he was looking to process. The first one was Ambient 2: The Plateaux Of Mirror, the Harold Budd record.

We only had a few boxes of equipment at the time. I had AMS boxes, British processing equipment, some Lexicon and some Eventide boxes. So we got all of those boxes running together and had them up on the console all the time. But we were not just monitoring the processing and special effects through the mix but we were sending those processed sounds back into the device, so we were printing as we went along. So if we were lucky enough to stumble upon an interesting sound, that sound got printed so it was not just documented and left for the mixing stage. What that did was to cement the processing as we were excited about it and allowed us to apply that processing to the processing again and that was the secret door that I walked through.

If the end of your chain is a processing box and you just have it up in your mix then you’ll never know what I’m talking about. But having printed effects meant they were now new tracks. And when we next put up the tape, those tracks were put up on faders and we could reprocess them meaning the same technique was applied again. So the second lot of processing got printed. We might eventually abandon the first generation of processing and only use the last link and that’s the stage when it got quite fascinating because that generation could be quite different from the original sounds and that’s when it could get pretty far out.

I got hooked on this way of working and I thought, "I’ll never look back". Beyond the specifics of the technique that I just described, it was just good to be devoted to a direction and I made a pact with myself that I would never do anything that I didn’t want to do again. So that was a turning point for me.

You were breaking virgin territory weren’t you?

DL: It was virgin territory because the boxes were not meant to be used in the way we were using them. We were pushing the boundaries of the boxes’ recommended use. A lot of these sounds have been mimicked through time and what was a question of clever routing at the time is now available in a music store. I’m not suggesting you can buy the sound of devotion but you can certainly have a large palette of sounds available to you simply by going to the music store. I think the limitations in sound at the time is part of the reason why we got good at those specific boxes. We only had a few, so we mastered the use of them.

Were you already aware of things like ambient and process music as actual philosophies and disciplines before you met Brian Eno?

DL: I was aware of some of these terms. I listened to electronic music from the 1960s but not in a profound way. I had a copy of Switched-On Bach [by Wendy Carlos] and had one of the first available Minimoog synthesisers. I had listened to some musique concrète and albums of treated piano, so I was aware of some of the forefathers in the field.

When I was a kid there was a night which had a big impact on me. There was an installation at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto and Pete Traynor [Canadian guitar amplifier and sound equipment designer] had installed speaker cabinets hung from the ceiling of this warehouse which was maybe a 5,000 sq ft room. He had what I remember to be 150 speakers hanging from the ceiling, about 5ft above the audience’s head and each one of those speakers had a sound coming from it. And it was electronic music so the sounds were jumping from one speaker to another. And I thought this was the greatest thing ever… I’m sure we were high on something or other but it really made an impression on me and I thought, "This man has challenged conventional playback systems here." He had a dozen sounds that kept on panning from one side of the room to the other – it was fantastic, a great installation. I knew I wanted to revisit that idea. These little observations along the way developed my interest in the unusual when it came to sound.

You worked with Eno on a few really important records – can you tell me how your relationship with him developed?

DL: Yes. We made half a dozen ambient records and when he wasn’t working with me in Hamilton he was living in New York. He was very hooked into the art and music scene there. He was working with Talking Heads, he was making My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts with David Byrne. So he was hanging round with the art people and intelligentsia in New York and by contrast I was isolated in the blue collar steelwork town of Hamilton. So I was really curious about everything he’d been through. He’d been to art school and I never had. He had history. He’d already worked with David Bowie, had been a member of Roxy Music and had made some fascinating records prior to me meeting him. So he held a lot of wisdom and information but he was a little bit more art school in his mentality toward music. I was more formally educated. I knew my way round harmonies. I was able to be very useful to him, in showing him valuable musical shortcuts. So we became a very good team. I can’t claim responsibility for Brian’s vision at the time but I was able to support him in every way. And we became a very productive team during that stage of ambient music.

The lap steel crops up a lot, either as an integral part of American cosmic psych rock or space rock, or as a signifier on spacey American indie, and as far as I can tell all these records seem to be influenced by your addition of country and western overtones to the Apollo soundtrack…

DL: The Apollo music was supposed to be a soundtrack to a film by Al Reinert about the manned missions to the moon. Some of those astronauts were from Texas so we added a little bit of a country twang to the outer space music, because it was something which they all liked. So suddenly my steel guitar came out in the studio…

When you were recording Ambient 4: On Land and Apollo…, were there any new techniques or applications or philosophies that you and Brian Eno came up with?

DL: We made use of the variable speed on this MCI machine that I had at the time. MCI is an American company based in Florida who make tape recorders. They had a very good, easy to use VariSpeed, which was right on the remote. Brian had written out this formula about how the various pitches you could get out of it were related to the speed settings, so we got really good at speeding things up and slowing things down and those speed changes would relate to the harmonics of music. Plus he had written out an elaborate table of pitches on our AMS Harmonizer. That also allowed the change of pitch, so we were able to change the speed and pitch of the sound which opened up this whole world of texture. For example, on the record Apollo…, on the song ‘Deep Blue Day’, that was slowed down a lot. It was played on a toy instrument which just had one button and if you pressed it everything happened at once. We played it kind of fast and then slowed the tape way down and it suddenly had this gorgeous jukebox bass sound. There was something special about it, and then we added all the other instruments on top of that, so the toppings are all done in real time and the bass was really slowed down.

Can you tell me about the cover to your new record, Flesh And Machine?

DL: The cover is a photograph of a boy who is about seven months old, which I manipulated and coloured. I put antennae in his head and he is looking up in profile as if to be a little seeker. There’s something celestial about him, it’s a bit sci-fi. But it definitely suggests that he’s looking for something that’s never been heard before. So he’s my little seeker, he represents the bit of me that’s always in the laboratory, experimenting, looking for new sounds and sensations. I want people to provide rising emotions. I honestly believe it’s my job on this planet to raise the spirit of sound. I’ve been able to do it a number of times on other people’s records. It’s still my job to raise this spirit and I’d like to think that I’ve done it on this record. The track ‘Sioux Lookout’ is meant to be a native chant or a cry for living things. So I decided to mix the sound of humans with the sound of animals. But they’re not animal sounds really – I’ve created all of these sounds myself but that’s kind of my aim, you can’t tell whether the sounds are animal or human. I got to this place of mysterious sounds. I’m inventing a new language, a new sonic language.

To what end?

DL: To create universal language. Why does everyone like Tinariwen from Mali? They don’t understand the language they sing in so that’s not it. Their songs are not burdened by familiar slogans or poetry. That’s the beauty or the potential beauty of an instrumental album: you can reach anyone or any ear anywhere. That’s part of my quest.

Is ‘Sioux Lookout’ acknowledging your own native North American heritage?

DL: I think it represents the native culture that I have been exposed to here. It’s not a new thought, the aboriginals, the natives have been beaten down and had everything taken from them and to this day there are issues with land rights, pipelines going through sacred grounds. It never stops here in Canada. And as industry expands into every corner of the country, there are more of these issues every year here. So without getting overly political, in ‘Sioux Lookout’ I hear the voice of my native mates and they’re calling for a balance.

When did you decide to make Flesh And Machine? When did the idea come to you?

DL: The record took on its own direction. I had songs. I tried a lot of things that I had in my head and in my notebook but it didn’t seem to be adding up to be my best work. It just seemed to be a little bit average. I thought that at this point in my life I didn’t want to be doing average, I wanted to push myself and push the limits of sound. I like the idea of pushing that symphonic button that we as human beings respond to but for the sounds to be unfamiliar. The track ‘Two Bushas’ is very symphonic and almost sounds like someone is conducting it but the tones and textures can’t be pinpointed. You wouldn’t say, "Oh, yeah, that’s a flute and that’s a cello." The result is a symphonic one. It appeals to that part of us that responds to orchestral music but with sounds we’re not used to. On a good day, if I was feeling full of myself, I’d like to think that I’m taking symphonics to the future.

Can you explain the name of the album?

DL: Well Flesh And Machine is a line that I’ve always walked. If you’re a studio-as-laboratory devotee as I am then you work with machines. I work with machines a lot. Machines are a big part of my life. But at the end of the day we want a sense of flesh. Authenticity is a big part of making music for me. So I chose not to use available electronic sounds, I used home-made sounds, be it my steel guitar, regular guitar, piano, drums or vocals. There are vocals on there – not that you would say, "Oh here comes the vocal part." There are samples of vocals that are essentially muted or kept hidden away. Then they become an available ingredient which we can expose in a very abstract manner.

So there are very few synthesisers on the album?

DL: There are no synthesisers on the album, bar one. At the bottom end on a couple of tracks we have my Moog Taurus pedals. On that really textural number ‘Rocco’ the bottom end is done on those pedals. I’ve not gone down the street of recording atmospheric sounds, all of the sounds on the album are from musical sources.

It’s not ambient music really is it? Say for example the track ‘The End’, which features you playing guitar and Brian Blade playing drums, that’s pretty hectic…

DL: It’s not meant to be peaceful and textural by any means. I think it has a lot of rebellion in it. ‘The End’, the real divebomb number, is a live track. I’m on guitar and Brian Blade is on drums and then everything else is processing. Brian and I have played together for a long time. Brian is from Shreveport, Louisiana, a preacher’s son who learned to play in church. I met him in New Orleans at a time when Iggy Pop was making an album in my studio in New Orleans. Iggy and I went out for a little walk and we heard this amazing drumming coming out of this cafe and there he was, young Brian Blade playing the drums. I’ve been hooked on him ever since. He is a powerhouse and a high-spirited young man. One of the greatest human beings I know. He’s helped me rearrange not only how I look at music but how I look at life. I’m happy to have him around.

The live session must have been pretty smoking improvised jazz rock fusion but it’s the processing that has made it really futuristic. Can you tell me what you did to it?

DL: There’s a lot of sampling of the guitar on that track. Once I have the sample I can change the octave or create a portmanteau effect. And at other times I get really subsonic with the samples to provide these bass notes. These samples, which I called dubs, have to be put back in in a very clever manner – in a way that is harmonically correct with the toppings. It’s not just a technical process, it is a very compositional process and hours and hours of work go into these tracks. Everything is cut from the cloth though. There are no added sounds from external sources so all the sounds you hear on that track come from the instruments that are there. So there’s always some sense of familiarity, there are no foreign bodies coming in to complete the picture, they’re all from the source.

There are a lot of different styles and approaches on this album because ‘My First Love’ is entirely different from ‘The End’ isn’t it?

DL: Yes. ‘My First Love’ features the same ‘Deep Blue Day’ toy instrument from Apollo… The same Suzuki Omnichord that was used on that track.

Is this ambient music?

DL: No. Andy Kaulkin imagined it would be at one point but it’s different. I’ve been preparing the tracks ‘Sioux Lookout’ and ‘Opera’ for the stage and it’s very exciting. I do live sampling and dubbing as well as playing as one part of a three-piece on stage. It’s very powerful. I’ve played a few shows with it here on the West Coast and people have said, "Well, we’ve never seen anything like this before." You’ll go to the big raves and you’ll see the DJs deploying crescendos but it’s a closed system and they’re just using files. There might be somebody onstage but they’re blending already prepared sounds. We do that but also perform as well. Our crescendos and our risings very much belong to the night, never to be played the same way again.

Do you have a preferred way of listening to a record to tell if it’s finished?

DL: I’ll listen to the music in cars. We have a radio transmitter in the basement. It’s not a strong one, it only reaches three or four city blocks but we transmitted the song from the studio and drove round the block listening to it on the radio. We go for drives in the car for a break and to listen to our music on those kinds of systems. Probably the best part of a car is the stereo these days. I like listening in different kinds of rooms. Especially other than the room you work in. It’s good to be in a totally different environment so you can get some objectivity.

You first started producing music with your brother Bob in your mum’s laundry room in the 70s. Are there any methods you used then that you still draw on now?

DL: Well, I always look for any original standout moments that happen during the day. There might be a little riff that comes out, a lyric, anything at all that suggests a point of sonic identity, I make a note of it and that’s on the menu for that record. Because we want records to be original and you’re only going to get that by earmarking your most original moments during the week. I call it spotting and when something happens in the studio, even if it’s only a tiny fragment I make a note of it where it lives and then I present it to the room the next day as something that belongs on the record.

Flesh And Machine is out on ANTI- now