I’ll never forget. 1994. A cold Wednesday morning in March. The Embassy Hotel, Bayswater. I’m sat down, inside, smoking cos you could back then, and trembling from head to toe. About to do the first ever interview I’ve ever done with a band. The first ever. Terrified, dry mouth – still get this now but then at a novice pitch of panic that was nauseating, like I was still in school and knew I had PE that day. I’m not from London, don’t know where or what I am, I’ve never broken the fourth wall and spoken with musicians before; I’ve never really spoken with anyone before. The band walk into hotel bar, say hello and shake hands.

Remember man, BE COOL, try and look human.

I put a cigarette in my mouth, light it, wonder why the band are staring at me with appalled fascination. Inhale and realise why – I’ve lit the filter end, am choking on fibreglass, cough my guts up, grimace, notice their slight pity for me, decide to exploit it, ask my first question. It hasn’t got any better since. Nostalgia, for me, has always been about pain. The neuralgia of times gone. The saccharine quinine hit of pure shame.

You and the music you listen to deserve each other .

I miss nostalgia. Not the stuff that gets talking heads spouting clichés. The stuff that hurts. The pains of ego, barricaded in on your own self-piteous spiral, poverty and loneliness and the inability to get used to either. The resignation that’s fake, that’s not yet mature enough to fully reconcile itself to the impossibility of reconciliation. Our past is now only touched on to recall wholeness, happiness, the good times, the sense of belonging that comes from hope, the hope that depends on a future. But what if all you remember is hiding? Your eyes behind your fingers, sun x-raying them blood red? Then the music that soundtracks your memory doesn’t just recall places, parties, sounds, times, locales. It recalls a cellular feeling, a tilt you had at the cosmos, the way you felt inside, the way you tried to stop feeling anything at all whenever you were outside.

Twenty years on I meet that band again. Twenty years on the band I’m speaking to are no longer a band, but still possess me, still come the closest to being my favourite band of their time, whatever that means. You and the music you listen to deserve each other. It fits you, suits you, moulds your moves and stasis. For much of the 90s I was proud to have Come on my shirt and Come in my ear. Sure there’s always music you slip into to feel cool. To strut. To adorn, to show and prove, music you want when it’s not there. But then there’s music you live in, hide in, NEED, so you make damn sure it’s always there, keep it close like a secret, wish it all the luck in the world but secretly want it to stay near, not get lost from you.

Come were music for the low times, for those cowardly moments of suicidal depression when you lay sprawled, dreaming of being found, those stopped second-hands and the yawning lurch of anguish in the guts, the anxious paralysis of knowing you’d just turned into an adult and have nothing to look forward to. For me, no question, Come provided the closest clearest soundtrack to the pain and anguish of my 90s and did so by making music that was narcotic in the fullest sense – a dissipation of pain with no lies about redemption. They mad an art that made you feel less alone by painting your daily despair in arcing waves of eternal light and shadow, glimmering shots of redemption and grey squalls of surliness.

First time I heard them was their debut song, ‘Car’ played by Peelie, and her voice, and her band’s sound, and the sheer desperate drive of the music stole your breath, made time tick on harder with a doomsday heaviness. This was a song that KNEW you, had SEEN the way you had fucked up every single relationship in your life. But beyond the lyrics it was the music, sculpted in pure feeling but with an innate artistic flair for weight, structure, shape and when to abandon all that. It had guitars that seemed to follow no order beyond the heart’s frenzied imprecations. The sound traced the moment you were in. It realised the moment you were in was frequently one in which you were waiting, waiting for someone, waiting for something, a change to come in your life, a hope you couldn’t believe you were still dumb enough to cling to, a hope you knew no amount of resignation could stop you being addicted to. Songs not in keys major or minor but somewhere always twisting in-between, sliding through the spaces between the notes, a chiaroscuro of focus and decay, being and nothingness, conjured by these Bostonians you knew next to nothing about.

As a Throwing Muses fan I knew how that felt, but I’d never heard it put quite as blue and black as this before, pushed quite so dazzlingly from such immigrant hearts and such shattered souls.

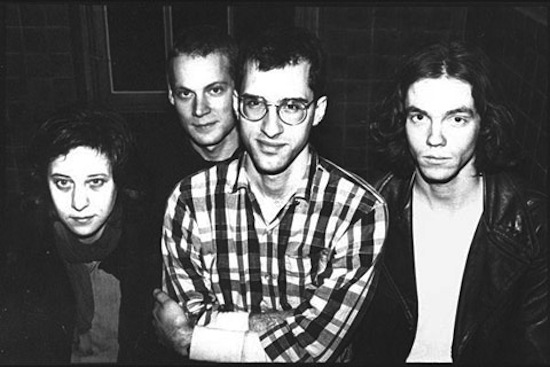

Chris Brokaw, who I spoke to in the last instalment of A New Nineties left Codeine to form Come with Thalia Zedek, one of the most unique voices of American music in the past two decades. Chris kindly hooked me up with Thalia again and I make sure my fag’s the right way round, light it, and fire away.

What was happening in 1989 and 1990 in your lives that militated towards Come forming?

Thalia Zedek: Me and Chris’s paths crossed first, I think around 1985 or so. I was playing in a band with some old high school buddies of his. Chris had just moved to town and they knew that he was an awesome guitar player and they invited him to come to a rehearsal of ours. The chemistry between me and Chris was immediate and I wanted badly to ask him to join our band, but we already had two guitar players and the other guys vetoed it. About a year later I moved to New York to be closer to Live Skull who I had been singing with for about 6 months at the time. Chris used to crash at my place in the East Village a fair amount and we would stay up all night playing guitar, and doing drugs.

Chris Brokaw: I’d seen Thalia sing once with Live Skull and thought she was great – we met one night and immediately went downstairs and jammed for about two hours, and it was one of the most exciting evenings of my life – the interplay between Thalia and I was immediate, incendiary, telepathic – totally exhilarating. I tried to play it cool but I went home and couldn’t sleep that night, I was so excited by what had just happened. I really wanted to join their band, but was too shy and insecure to really try to make that happen. Thalia and I started getting together, usually in New York, and playing for two or three days at a stretch, just jamming and talking about what kind of music we wanted to play.

We were both playing fairly esoteric music at the time – she was in Live Skull; I was drumming in a band called 7 Or 8 Wormhearts that had two singers and two tuba players! We were both interested in doing something that involved more traditional rock & roll song writing. We were especially drawn to The Rolling Stones, the Gun Club, the Only Ones, the Jacobites and the Birthday Party and all their spinoffs. We didn’t want to deliberately be like any of those bands; but that neighbourhood was a rough reference point.

How did things grow from just you two to a full band?

TZ: Later I met Arthur [Johnson, drums] and Sean [O’Brien, bass]. Arthur was playing in the BBQ Killers and they opened up for Live Skull. We were all completely blown away by their music and energy and wild stage show (think Butthole Surfers without the props!) and we asked them to tour with us. So I watched Arthur play drums every night for like four weeks and was blown away by his drumming each time.

I became romantically involved with the singer for BBQ Killers, Laura Carter, and started visiting her in Athens GA a lot. It was a tight little scene in Athens back then and everyone knew each other and hung out together. Eventually Live Skull dissolved and I moved back to Boston. I looked up Chris as soon as I moved back and told him that I wanted to start a band with him. I actually had both Arthur and Chris over to jam in the basement of the house where I was crashing on the couch. Another band was already playing there and they let us use their equipment. But I was really too fucked up on drugs at the time to make it work out. Sean O’Brien eventually moved to Boston as well as part of the great Athens GA diaspora. I was a pretty big mess at the time though.

But you cleaned up?

TZ: Yeah… Eventually I managed to get off drugs and I ran into Chris who had also cleaned up his act in the year or so since we last hung out. I know that Chris thinks otherwise, but in my recollection ‘Car’ was the first song that we finished, though there were probably two or three "jams" that we wrote pretty much immediately.

CB: She’s wrong. The first song we wrote was ‘Last Mistake’ which I thought was kind of funny, in terms of the title. I think ‘Car’ was second. We wrote those songs together in Thalia’s attic bedroom. I distinctly remember working on those up there, as well as ‘Submerge’. I remember ‘Brand New Vein’ coming out of a jam. ‘Dead Molly’ and ‘William’ originating in the basement of this Brazilian restaurant where we rehearsed for a while.”

Was there ever a typical Come ‘process’ when it came to song writing? Were you writing about relationships on-going or long-gone?

TZ: I think Come worked in a few different ways. In the early days I’d say that we probably wrote 80% of the songs out of jams, and the other 20% came from ideas that either me or Chris came up with on our own. I wrote all the lyrics and vocal melodies. I think the songs on 11:11 mostly dealt with fallout from my time living in New York and being a drug addict and also of the strangeness of kind of waking up on the other side of that period of my life. A fair amount of looking back, a fair amount of struggling with the present.

CB: Come practised twice a week, Tuesday and Thursday evenings. The structure of band practice was usually: jam for an hour; play/work on songs for a while; play some covers. We had a cassette boom box and whenever we’d get into something interesting in a jam we’d press ‘record’ and go back and listen later. Sometimes there’d be a riff we’d hammer on for 20 minutes that might eventually become two or three seconds of a finished song. We worked on songs for a really long time. Besides practising twice a week with Arthur and Sean, Thalia and I would get together once or twice a week. She and I would sometimes come up with half a song, or some ideas, and bring it to the other and finish it together. There were a few songs that each of us brought to the table more or less finished – Thalia with ‘Sad Eyes’, me with the chords and melody of ‘German Song’ – but most of the songs involved a lot of collaborative piecing together.

Essentially, Thalia and I wrote the songs, but we gave Arthur and Sean equal song writing/publishing credit because their playing was so essential to how those songs came out. I had the sense even early on that song writing credits were a big source of contention for some bands, and I wanted us all to feel like we were sharing equally on the work and the rewards, whatever they might be, which always seemed like they’d be… I don’t know, small perhaps? I had very few expectations about making money from music

So was 11:11 simply a collection of the songs you were playing at that time or was their more thought as to what songs would hold together as an album-length narrative?

TZ: The songs on 11:11 were all written in roughly the same period, with the exception of ‘Off To One Side’ which was an old song of mine from my Via days. We were pretty much a "basement band" up until then and didn’t really know how people would react to our music. We were super relieved and psyched that the songs seemed to have a strong effect on people. Jonathan Poneman from Sub Pop had been in New York talking to Codeine who Chris was still playing with at the time. He heard about us and came to Boston and saw one of our early shows. He really dug it and soon afterwards asked us if we would like to do a single for the Sub Pop single of the month club. That single was ‘Car’ and ‘Last Mistake’. I’m a little fuzzy on whether we recorded that before we recorded 11:11 or at the same time, but all the songs were from the same period.

CB: After the fact, we all noticed that the word, or idea of, ‘waiting’ was central in 11:11. We didn’t write a ton of songs. We recorded basically everything we ever wrote. We dumped a couple of songs; and there were some things that never reached completion – but basically we’d write an album’s worth of songs and that would be the album.

Quick side-track – I love and cherish my 10” of ‘Fast Piss Blues’ as much as my 12” of ‘Car’ – these didn’t show up on the vinyl of 11:11 – was FPB recorded before or after 11:11? Whose idea was the inspired cover of ‘I Got The Blues’?

TZ: ‘I Got the Blues’ that was my idea. I was pretty obsessed with Sticky Fingers and had taken to occasionally playing it solo at Live Skull shows for reasons that are a bit hazy now. But playing it with Come and particularly with Chris’s guitar and vocals really took it to another level.

CB: In a way, it was us saying, "Oh, so we’re a blues band? HERE’S your ‘blues’ single." Kind of stupid. But a good single.

One of the things definitely overstressed I felt in the writing about you at that time was that word ‘bluesy’ – betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding, or rather overly-superficial understanding of both the blues and what you were doing.

CB: I agree. I never thought we were a "blues band" or anything like that. i think we all liked some blues or blues-based music, but, personally speaking, a lot of those influences were second or third hand – like, I was really into Jorma Kaukonen, and learned a lot of his versions of old blues songs. I think at some point it was a handy reference point for rock writers, in trying to describe what we were doing, but, it was kind of inaccurate and reductionist. It didn’t really matter that much to me, I was happy that people were writing about us.

As a massive Stones fan I could definitely see how you used guitars in a non-egoistic non-soloey way, you both intertwined to the point where individual styles became indistinguishable. I’m guessing you two are the only two people on the planet who can listen to that album and know who played what!

CB: There is something of the way that Keith Richards and Ron Wood played together on the Some Girls album, yes. Where neither of them are really playing rhythm or lead guitar.

There’s also a sense whereby, if the rest of US rock at the time was obsessed with fuzzing/grunging everything to a point of imprecision and excess Come were painstakingly precise music, the guitars never just simply adding to the wall of sound but picking out all those melodies and harmonies the vocals weren’t (although your harmonies were incredibly sweet too).

CB: Yes, the music was really precise. And we didn’t really ‘jam’ a whole lot once the songs were finished. I was listening to Charles Mingus a lot at the time and in hindsight i think that music had a big influence on what i was doing; i didn’t think so at the time, but maybe hear it a little now.

11.11, slated for reissue on May 7 on Matador in the US and Glitterhouse in Europe, saw Come move from Sub Pop to Matador and it still stands as one of the most stunning debut albums of the 90s, up there in ’92 with Slanted & Enchanted, Red Heaven, Angel Dust and Check Your Head in most smart folk’s end of year lists, for me better than all of them. The Come sound would’ve been devastating enough by itself, but coupled with the band’s hard-boiled, poignant tightrope walk ‘tween realism and romance it seemed to emerge from a place simultaneously familiar yet curiously unprefigured by anyone else. You accepted the words writers tried to capture it’s majesty and grace with, but you were always aware that this music occupied an entirely unique space in your head and heart, that beyond even their legendary sources, Come were impossibly making music for right now that sounded like it could last forever. I wasn’t the only one, St. Etienne’s Bob Stanley, Kurt Cobain, Kristin Hersh, J.Mascis & Bob Mould were among others proclaiming Come as the best new band in America.

CB: I love that version of the band. Definitely my favourite line-up. I’m happy that 11:11 was recorded and mixed as well as it was. Considering that it’s basically a recording of a band playing in a room, with almost no overdubs at all, it has… a richer quality than that. Somehow it sounds or feels like more than that. I don’t know how we achieved that quality, but certainly we have to credit Tim O’Heir and Carl Plaster for doing such a great job recording and mixing it.

TZ: I think in Europe much was made of the depressive aspect of our music and of my druggy past and we were portrayed in a way that I felt really uncomfortable with. I guess it was because it made for an interesting read, but I would literally cringe reading some of the reviews and thinking about how my family would feel if they read it. The American reviews tended to focus much more on the music rather than trying to psychoanalyze me and I think I felt more comfortable with that, though I realized that the European reviews were also extremely positive in nature. I think 11:11 was received just as favourably in the States as in Europe, but maybe with less hyperbole in the US.

CB: The reception was really good, virtually everywhere. The UK press was really over the top, and painted this apocalyptic view of the record that was kind of absurd and probably unnecessarily distracting. Certain phrases like "listening to 11:11 is like waking up in the middle of your own autopsy" took on way more weight and real estate than they should have! It’s strange to think about now, but at the time it felt like the UK press had incredible importance to our career… that was just the environment we found ourselves in. I think that was widespread, but certainly true with our management at the time, who worked the UK press really hard. There was something of a Next Big Thing buzz in the air, which we never quite believed; we really tried to just concentrate on what were were doing musically. There were other Next Big Thing bands that we were briefly lumped in with (Hole, Afghan Whigs, Urge Overkill) who seemed, in virtually every regard, to be better suited to rock stardom. I don’t know. We would play one week in the punk rock dives with Rodan, and the next week in the big UK halls with Dinosaur Jr. or Throwing Muses, and we weren’t always sure which neighbourhood we were supposed to be in. We figured if we stayed the course with what we wanted to do musically, we would end up… wherever we were supposed to be. We were not particularly calculating careerists, that’s for sure. And there was a lot of that going on all around us. I feel good about the choices we made.

A pattern starts emerging – much as early on you spent a year of rehearsing before recording anything, it then takes you a year between 11:11 and sophomore album, Don’t Ask Don’t Tell – is this simply a matter that it took that long to hone a Come song to perfection or was Come a difficult band to actually convene.

TZ: I think the fact that we were given the opportunity to record a record so soon after playing our first show was a big part of the time we took between 11:11 and Don’t Ask. We had literally just written enough songs to be able to play a 45 minute set and didn’t have any left over. Because so much of our writing at the time came from jamming in the rehearsal space it was virtually impossible to write anything on the road. We were almost always the support band in those days and would usually only have a few minutes to sound check before a show if we got to sound check at all, so there was no time to jam on ideas until we got back from touring, which was possibly a year later! In retrospect we probably could have tried writing in hotel rooms after the show and the like, but our schedule was pretty hectic and there were always a lot of interviews and such to do before and after shows as well.

CB: In part it was us spending a lot of time working on songs, and in part it was us spending a lot of time on tour. And we never really wrote much while on tour. We toured for about seven months on 11:11, and by the time we were done I wanted to destroy our songs. I think we only had 12, and we had to play them all every night for seven months! We actually turned down some "high profile" tours we were offered because we needed to spend time at home, just being normal people and working on songs. We never became one of those bands that are on tour all the time. We toured a lot, but maybe not enough? Evan Dando once told me that to properly promote a record you have to tour it for 11 months, and I think he might be right. At any rate, we came home and worked on the songs for Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, which I remember being really hard to write; a lot of work.

By the time of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, Chris you’d left Codeine, did this enable you to focus more on Come than before?

CB: Yes, totally. Come became my one and only band. The music became more layered, more layered feedback parts. ‘Finish Line’ felt ambitious in a way we hadn’t attempted, at that point. Certain songs like ‘In/Out’ and ‘Poison’ came in part out of a desire to have more fast songs to play live. Certain songs like ‘Let’s Get Lost’ and ‘German Song’ had a kind of magic we didn’t necessarily control ourselves.

I remember being hella nervous before hearing Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. In the intervening two years since 11:11 I’d become a writer, got the album sent for free but it still felt like your whole being and belief were at stake with Come, so close did they feel. Would they do the same-old? Would they make a mistaken lurch elsewhere? Come, instinctively & intuitively & gloriously, managed to move on, refine, perfect their amazing art, push their song writing into longer even-more captivating breadth, always with the ever-awesome Mike McMackin on the mix.

TZ: Mike was someone that Chris had worked with in Codeine and he really wanted him to have a hand in recording the second record. Carl Plaster did the drums for 11:11 and had done a lot of live engineering for us as well, so we thought that by combining the two of them together we would cover all the bases. Unfortunately it didn’t work out too great for a lot of different reasons, most of them entirely unpredictable and technical in nature. We ended up with an unmixed mess of a record and our manager at the time recommended Bryce Goggin, who had just recorded Crooked Rain Crooked Rain with Pavement. Bryce did an incredible job. He basically saved our asses and the record and we continued to work with him for quite a while afterwards.

CB: Mike McMackin didn’t actually do that many records, but I was on three of them! I had really liked the icy quality he brought to the Codeine records, and I thought it would be interesting to combine him with Carl Plaster. It turned to not be that great a combination – they got along well, but had really opposed instincts, sound wise. They spent a lot of time dismantling one another’s mixes… between those issues and the many troubles that plagued the studios we recorded in (floods, ice storms, etc) it’s a miracle that record got finished at all. It was a really difficult and expensive record to make. Wildly difficult to sequence. I remember sitting on the floor of my apartment at 5am with all the song titles written on note cards, throwing them all in the air over and over and seeing how they landed… it got like that.

Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was a loaded title – the unofficial phrase meant to deal with the ‘problem’ of gays in the army became official military policy in the US in late 93 – it’s use by Come highlighted the fact that there was always a political bite to their music. This was more than just traditional rock; it had an incorporation of ideas about being a dissident (esp. the feeling of being an immigrant in a foreign land – crystallised so perfectly with the next-to-first line I ever heard Thalia sing "I don’t remember being born/I don’t know where my mother’s from") that seemed to suffuse through both the lyrics and the music (which frequently seemed to be pulling on European folk influences as much as more traditional US rock motifs).

Am I barking up the wrong tree entirely here?

CB: It’s definitely a political reference, and we were definitely pointing up the absurdity of the policy. But we also wanted it to be open ended… I feel like it referred to secrecy, how some people around us were living.

TZ: I think the phrase, ‘don’t ask don’t tell’ just struck me as such a perfect example of how it felt to be queer in a ‘straight’ world. Like everybody ‘kind of’ knows and is ‘kind of’ cool with it as long as you don’t actually tell them ‘I’m gay’ and force them to acknowledge it. So there’s that aspect of it. I think also that at the time I was feeling kind of freaked out by some of the press that Come was getting and the way in which I was being portrayed in some of the articles, so it resonated with me on that level. And I guess linguistically I just found it to be an interesting phrase. As far as the political aspect goes, I’ve always had pretty strong political convictions but I’m just not a protest songwriter, that’s not what comes out of me when I sit down with a guitar. But being gay and living in New York in the 80’s when AIDS became a full blown crisis I definitely felt that I had to stand up. On the last Live Skull record Positraction I purposely wore an Act Up T-shirt and I was going to a fair amount of their protests in New York at the time. But I think that in general I fall into the majority of Americans meaning that I’m a pretty self-absorbed and selfish person and it takes something like AIDS or someone like George Bush Jr. to get me riled up.

In-between DADT and the next record (96’s Near Life Experience) your amazing rhythm section, Sean and Arthur, departed – was this entirely amicable?

CB: Arthur decided to quit the band in part because of the aforementioned difficulties in touring so much and trying to maintain a ‘real job’ at home. I think he also didn’t like touring so much in general, and missed his wife a great deal while we were away. Sean wanted to move to New York and work in the film industry, which he’s done – he works on movies as a grip. It wasn’t acrimonious, though it was a huge bummer. Those guys quit, we got dropped by our management, and we got dropped by Beggars Banquet, all pretty close together. 1995 was hard! But Thalia and I rallied and were like, "Fuck all y’all, we’re not done" and just soldiered on. It was hard but we were scrappy and we really wanted to keep playing. And we wanted to keep calling it Come because it felt like we were continuing on, musically, with what we’d done so far. It felt a little weird to keep the name, without Arthur and Sean, but not too weird. We knew there were many songs we could never play live without them – their playing was too integral – but we felt like we wanted to keep on and keep moving forward.

TZ: Arthur and Sean’s departure came as an utter shock to me. I was totally stunned but it never even crossed my mind that it was the end of Come. By this time me and Chris were doing the majority of the writing, due to the difficulty of writing together on tour. We still would jam a lot all together, but then me and Chris would get together on our own and pick through the rehearsals and work together on the stuff that seemed the most promising as well as writing separately on our own. At the time there was a lot of pressure on the band to be more prolific, to have scads of recorded but "unreleased" material for compilations, promos, etc. and the old way of writing seemed painfully slow. In retrospect maybe this made Arthur and Sean feel a little left out. “

When exactly did the split happen?

TZ: They left right when we were about to begin work on our third record and we had no songs yet. Don’t Ask Don’t Tell had not been very well received, particularly in Europe and morale was not extremely high. Me and Chris would get together in the laundry room of the house he was living in and work on songs together, as we had lost our rehearsal space and couldn’t afford another. So we just said fuck it, let’s figure out who our dream rhythm section(s) would be and ask them if they would record with us. We came up with Tara Jane O’Neil and Kevin Coultas from Rodan who had just disbanded, also ideal for us in terms of touring, Mac McNeilly from Jesus Lizard and Bundy Brown, an old friend of Chris’s and the bass player in Tortoise. We asked John McEntire, another old friend of Chris’ if he would engineer it for us and he said yes. He was working at Idful at the time so we rehearsed in Louisville and Chicago and recorded the basic tracks there, then brought it back East to finish it up at Fort Apache with Paul Kolderie and mixed it in NY with Bryce Goggin. In terms of feeling more freed up after Arthur and Sean left, I guess I did but only in the sense that there were now only two people who had to come to a consensus, rather than four. It was tough to lose them for sure.

CB: We just thought, ‘Let’s find some dream rhythm sections and record with them.’ The original line-up of Come had just recorded an album backing up Steve Wynn from Dream Syndicate called Melting In The Dark which had shown us that you can teach stuff to people really quickly and still make a good record; I know that experience was inspiring to me in thinking that Near Life Experience would be possible. We asked Kevin Coultas and Tara Jane O’Neill because we’d played some with Rodan, who had just broken up, but were one of our favourite bands on earth; I knew Bundy and loved his playing; I was a huge fan of the Jesus Lizard and loved mac’s drumming. We just asked, and everyone said yes. We couldn’t believe it! My hope was definitely for us to keep playing, keep recording and keep growing as a band. That was all we wanted. All I wanted, anyway! Matador and Domino allowed us to do whatever we wanted, artistically. I never really expected to be able to make a living from music, and didn’t until i went solo, oddly. Our inability to do so was actually not that big a deal to me. I worked in a restaurant, waiting tables, which allowed me the flexibility to tour as much as I wanted and still have a job to come home to. For some other people in the band that situation was much harder, and our inability to make the leap to all totally making a living from music was very difficult.

The cliché would be that the album that came from this would be disjointed but the solidity and surging rage of Near Life Experience gave no hints that anything of the sort had happened. The album was if anything a little more furious than anything Come had given us before, the sound less murky, more trebly, angry, pure sheets of noise firing across the sound like lightning at the end of lead-off single (‘Secret Number’) It sounds driven by demons, perhaps precisely because of the need to reaffirm that Come were still going. It’s also the first time I think that Chris takes lead vocal on a few songs. Did you feel freed up from the old band structures a bit more (also thinking of the trumpet on ‘Bitten’) consequently this is the most studio-borne album of the lot?

CB: Yes, totally, maybe a little embattled feeling. I sort of felt like since it was just the two of us that maybe I should step up and contribute more, or in more ways. And yes, opening up the record to Jeff’s trumpet and John McEntire’s vibes – that was definitely in the air at the time, too: bringing in more sounds to the palette.

As ever, once the album dropped and the shows blew thru, Come vanished, back across the water, and us fans waited until the next transmission. Gently Down The Stream came in 1998.

I remember seeing you live in London again just after this album came out (you started with ‘One Piece’ as I recall and it just melted my mind) and thinking with typical dim-wittedness this was a band with a future. Why did Come end?

TZ: The last thing that we did before recording ‘Gently Down The Stream’ was an "unplugged" type tour with Beth Heinberg on piano and Nancy Asch on percussion, both of whom were old friends of mine. After that Chris said he really wanted to make a heavy rock record and that he had heard from a mutual friend, Tammy Bonn, about an amazing drummer who was a big Come fan and also available. This man was Daniel Coughlin, and I actually continued playing with him up until a couple of years ago, so we played together for 15 years in total. We continued the song writing process with Daniel and Winston Bramen on bass. Winston was an old friend who played in a band called Fuzzy and was one of my favourite bass players in town, I still play with him to this day, he actually just recorded with me for a new record that I have coming out on Thrill Jockey in March. So Winston recorded Gently Down The Stream with me and Chris and Daniel, but he was still in and very committed to Fuzzy and so he couldn’t really do much touring with us. In retrospect I think that I probably knew that Come was coming to an end after Gently Down The Stream. Record sales and club attendance was either flat lining or dropping and me and Chris were starting to move in different directions musically. Him more towards solo instrumental music, which obviously left me out, and for my part I had fried my ears from years of playing small clubs with lousy monitors and I had become tired of screaming over loud guitars and wanted to write and play music with more subtlety.

It was heart-breaking when news trickled thru that Come were over, but there was a definite sense with Gently Down The Stream that they were straining against the ultimate possibilities of what Come could do, but were still pushing ahead with stunning songs and playing. You got the feeling that both Chris AND Thalia had said everything they wanted to say together. But my god what a legacy, four albums that remain pretty much a high-watermark in beauty and wonder, four albums that remain some of the greatest American music that country would EVER give us.

Will you both write/play together ever again? Crosses fingers. Lights fag, filter end for luck.

TZ: Me and Chris have collaborated many times since Come ended and played many shows together, we have not however written any songs together since those days. If it ever happened that we did write together again, I would be totally psyched though.

Anyone ever touched by what happens when these two genii get together would feel exactly the same. Fingers crossed. Lungs and hearts on fire. Never forget them. Never forget.