Four decades after its release, the Young Marble Giants’ Colossal Youth remains one of the independent/post-punk boom’s most wondrous creations; lean, uncluttered yet emotionally stirring. The fragile arrangements of brothers Stuart (guitar) and Phil Moxham (bass), refracted through Alison Statton’s understated vocals, conjured an enduring, singular statement. One of Rough Trade’s biggest sellers, it anticipated the ‘quiet revolution’ that was one of the tributaries of post-punk, and has been mentioned in despatches by everyone from Everything But The Girl to Peter Buck and Kurt Cobain.

You grew out of the Cardiff independent label/collective Z Block. They were heavily influenced by the Desperate Bicycles and Scritti Politti’s DIY singles – was that true for you?

Sturart Moxham: No, not at all! I was more or less completely oblivious to all that. I had a very parochial attitude. I remember watching the Rough Trade documentary on The South Bank Show [1979] and thinking ‘Pah, bunch of lefties!’ But it was magical that you could make a physical record. The whole Z Block thing was a revelation. You didn’t have to go through the hierarchy, you didn’t have to fight the fact that you were in Cardiff and no one gave a flying one – you could actually do it yourself.

People see post-punk, in its various forms, as a reaction to or a progression from punk, but it sounds like you developed in splendid isolation.

SM: Personally I didn’t like punk rock. Musically it was rock ‘n’ roll all over again, just a bit faster, with puerile spitting and swearing; a very limited London thing the music press blew up. It was only in retrospect that you realise it was a huge catalyst and essential. You have to bear in mind that I was 25. I’d grown up listening to all the rock giants, Motown, progressive rock. I was a long-haired Led Zeppelin fanatic at 14. The Beatles, Stones; that’s the background I came from.

At 25 you probably have defined tastes.

SM: Yeah, although I was still very much excited. Looking back, we were on the cusp of a massive technological change in music. The cassette was new. Wow, you can do your own recording on a tiny portable machine as an alternative to vinyl. Synthesizers and Fairlights were coming in, and samplers were on the horizon. One of the sexy things was the drum machine. We were into Eno and Can and Kraftwerk. There was an attraction to getting away from conventional instruments.

If drum machines hadn’t been available, do you think you would have found a drummer?

SM: No, I don’t think we would. There was an element of liking the cheesiness of the drum machines [a feature Kurt Cobain specifically approved of]. There’s a lot of humour in the Young Marble Giants. The Testcard EP is doffing the cap to Butlin’s, end of the pier rhumba rhythms, and daytime TV music.

Several artists have credited YMG with making ‘quiet’ music permissible again after punk.

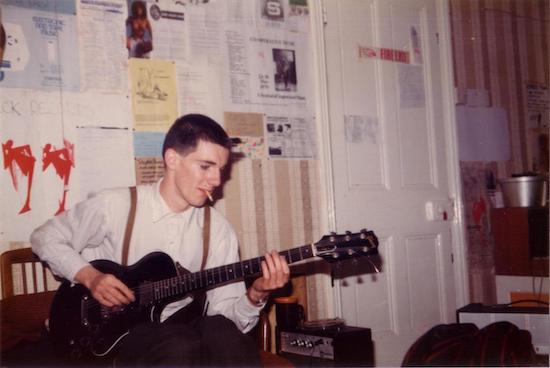

SM: We were on a hiding to nothing. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I was quite an unhappy 25-year-old, really. My friend introduced me to playing the guitar and it was a massive catalyst. If I was going to anything in my life, this was how it was going to happen. But we were in Cardiff; we had no money, we were all unemployed. That gave us the time to work out what we were trying to do. But nobody we knew had ever been successful through music. None of us thought it was ever going to work. So what we had to do was be as noticeable as possible. And in the era of punk and noise and aggression, the obvious thing to do was go the opposite way. So the whole minimalist, ‘quiet’ thing was a sort of conscious choice. It was about getting attention.

You were the main writer in YMG. The other two are in a relationship, one of them is your brother. How did that unusual triangle inform the writing?

SM: I knew Alison would be singing the songs, so they were written from a female point of view when appropriate. Basically Phil and I did the music. We’d both sit down and work out arrangements. We decided that the bass should be a melodic instrument up front. It was all part of the post-punk ‘shake it up, make people think about music again’ thing. And by default the guitar became this percussive, rhythmic, muted thing, almost behind the bass. We weren’t conscious of that at the time but it seemed the right thing for us. I think another massive input into the Young Marble Giants was brevity; because we thought nothing was ever going to happen. It meant everything, and at the same time, you knew it was doomed. So you were giving your all but it was a waste of time!

It’s fascinating you say that you think the songs were doomed.

SM: There was no precedent to musical success. Rough Trade represented the only light at the end of a long, long tunnel. I was on the point of leaving to go to Berlin. And also the old chestnut of not wanting Alison in the band [she only joined YMG at Phil’s insistence]. The whole thing was disintegrating. And then we made the record and it was an incredible success and it took off. It forced me to think, well, between us, we really are capable. We have some talent.

Did that moment of realisation come in the studio, or was it when other people verified it was a good record in terms of reviews or sales?

SM: I think both things were the case. We were confident amongst ourselves that what we were doing was good.

Despite the success, you broke up following a tour of America.

SM: It was kind of too big to handle. Almost like an out of body experience. You’re doing it, but you don’t quite engage with it. And, of course, the consumption of marijuana had quite a bit to do with that!

Re-reading Simon Reynolds’ sleevenotes to Colossal Youth, there are a few euphemistic references to smoking.

SM: There was nothing euphemistic about it, I’m afraid! Of course, at the same time, inside that little bubble, there was no communication going on between us. We were getting further and further apart on a personal level. Phil and Alison were splitting up. It was just going to crap, basically.

So you weren’t able to enjoy America?

SM: Well, it’s different for each of us. Phil hated being in the public eye. Alison has always been nervous about being on stage. I’m a born show-off. I love being in a van on the M1 at three in the morning. But we hadn’t any plans to deal with it. We hadn’t allowed for the possibility of success. So we bailed out, basically. It took 23 years for us to be in a room together and talk about the possibility of doing something new.

Not tarnishing that legacy has probably helped the stature of Colossal Youth.

SM: Yes. That, of itself, is a real pressure. We reconvened in order to try to do a new album. I believe, totally, we can do that. I have no doubt whatsoever. There is so much bubbling up in us. Very slowly, that’s happening. My cunning plan is, by doing these gigs, spending time together and having a good time musically, we’ll start to thaw out.

The deluxe edition of Colossal Youth was issued by Domino in 2007. Stuart’s latest album, with Louis Philippe, The Huddle House, is available from iTunes and eMusic.