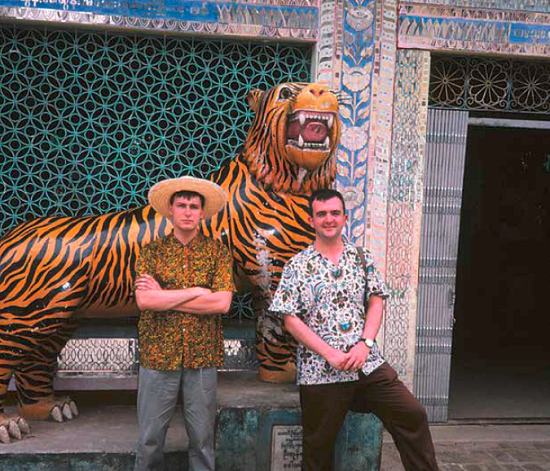

Photograph courtesy of Ossian Brown

For the California-born, New York-based writer Derek de Koff, the opportunity to interview one of his all-time favourite groups, Coil, was a “life highlight”. The English industrial/experimental noise duo, comprised of John Balance and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, had long been an obsession for de Koff when he was finally offered the chance to speak to them in 2001. Coil were in New York City to appear at the Convergence 7 gothic/industrial music festival in Irving Plaza; the interview took place at Manhattan’s Nothing Records, shortly after their festival set. According to de Koff:

“This interview was the only time I met them face-to-face, and the concert at Irving Plaza – as part of the Convergence 7 festival – was the only time I saw them live. It was a particularly screechy hour-long set based primarily around Constant Shallowness Leads To Evil; a soul-bendingly abrasive release even by Coil’s ‘bowel-churning’ standards. Classics like ‘Amethyst Deceivers’ and Horse Rotorvator’s ‘Blood from the Air’ gave way to the clanging, chortling ‘I Am The Green Child’, eventually culminating into the ‘Tunnel of Goats’ suite, an ear-shattering battering ram of analogue synths.

"By the end of the set, John Balance was writhing around in a straitjacket and banging his head against a sheet of metal, held aloft by two young men wearing only their tighty-whities (which weren’t entirely white; they were flecked with stage blood). Peter "Sleazy" Christopherson tinkered placidly over his MacBook as Balance continued bashing his head against the metal, making it rattle like percussion – and perhaps that wasn’t stage blood on his forehead. During the climax, the words “God Please Fuck My Mind For Good”, a line by Captain Beefheart, flashed against the screen. The performance lasted only an hour, and by the end of it, the audience looked as though they’d just been put through an abattoir.

"I’m pretty sure that concert was the only time that Coil ever performed in the United States. I was nervous at first, but they were so disarmingly friendly and open that the scope of the interview quickly swerved away from the printed piece of paper visibly shaking in my hand, and became more of an informal chat.”

This interview was previously published on a Coil fansite which no longer exists. Thanks to Derek for asking us to publish it on tQ

Forgive me if I’m a little nervous, but I’m a huge fan of your work.

Peter Christopherson: That’s quite all right – just as long as you’re not our "number one fan".

Your show was amazing, although I missed some of the last section. My friend ending up getting sick near the end: three vodka gimlets on an empty stomach. It started somewhere during ‘I Am the Green Child’.

PC: Well, it’s quite appropriate, then.

So, I wanted you two to talk a little about what seems to be a rekindled interest in blood.

John Balance: You noticed, then?

Well, there are new T-shirts that show you [Balance] covered in blood, and a vintage edition of Musick To Play In The Dark whose front cover is smeared in your blood as well.

JB: [PULLS BACK HIS SLEEVES TO REVEAL ARMS LACERATED WITH SCARS]

Oh! You’re not kidding, then. What brought this about?

JB: Just frustration, actually. But it turned into a psychotic break. I smashed my head through a window at our house, but luckily it was Victorian glass, so it broke in chunks and not shards, which was a God-given miracle. A Goddess-given miracle. It didn’t cut me, really. Well, only a little bit, but not much. So then I went downstairs and started attacking my arms with the glass. But by then, I’d already worked it into a magickal thing. I thought, "I’m in a real rage here. I need something to shift, and I’m not sure what." So we – he – Peter – fortuitously, foresightedly grabbed these blank album covers and smeared them on my face and arms. And then we made a recording with the broken glass. I had reached more than a red rage. You know that state? It just carried on. It took about a week to calm down from it.

PC: Sometimes your demons are useful. But sometimes they actually prevent you from doing things.

JB: We have a "feed your demon" theory. Some demons need banishing, obviously – especially those that have been given to you by someone else. Also, there are God-given demons. And then there’s those you inherited because of your existent genetic matter. But you’ve created a demon. And I’ve got those and I use them. They’re grit. Talking about homogeny and things, and why things feel so safe these days, people don’t have enough grit.

PC: It’s like those animals that have to have grit in their stomach.

JB: Those are chickens!

PC: [LAUGHS] I knew it was something like that. We were talking to someone earlier about musicians who have alcohol and drug problems and who get clean. It’s obviously good from a health point of view, but then they become sort of boring.

They do. Why do you think that is?

JB: Well, I’ve sort of dabbled with rehab, and this is a real stumbling block for me. Because getting clean is about seeing the results. Wonderful for the family and all the emotional upset stops – but I think everybody is addicted to something. I think it’s a gift in a way, because I can create music from it.

PC: Addiction is about trying to change the way we feel. And it’s a question of what we use to change it. Because everybody wants to change the way they feel. It’s part of human nature. And I think it’s not even a human thing. I think animals do it as well.

JB: And we are animals, of course.

PC: Of course. What we try to do is make music that permanently and fundamentally changes the way people feel and people understand their environment and the place they’re at in the world – and hopefully not do it in a way that’s damaging to their health.

With Musick To Play In The Dark 1 and 2, you were consciously playing with lunar energies; it was a more gentle, tidal sound. But Constant Shallowness Leads To Evil is anything but gentle. What are you playing with here?

JB: Lavishness is my stock answer for this. There’s too much of everything.

PC: There are too many magazines! You go into a magazine shop and you can never find the one that you want. There’s too many of them. And there’s too many CDs. And there’s too much choice in the supermarket. You can never decide what brand of…

JB: I was trying to buy some mouthwash, and the choice of mouthwashes lined across an entire wall. And I turned around, and there were more! I thought, "You only need the one."

PC: But we’re not against choice.

JB: No – but at the same time, this is a response to the overwhelming choice.

PC: It takes so much time to think about all these things that you almost can’t think about the things that are important.

Having too many options ends up the same as not having enough.

JB: Yes. Definitely. It’s that, and it’s about our frustration with consumerism. I don’t want to sound like a communist or something, because I’m not. There’s just too much stuff around us, and people – people – have been forgotten about. I’m sort of talking about homeless people and people who need treatment for drug addictions – but people! We were talking to these two nineteen year olds the other day, and they were saying, "No one’s ever tried to bond with us like this for a while." Except, you know, their gran. And this is why we’ve come out to tour. It’s not to smell the audience – I know that’s a terrible, KISS-like thing to say – but to actually meet people and bond with them.

You’ve said that this concert is an invocation to Pan. I was interested in what this means, in relation to Pan and panic.

JB: I think it’s getting straight back to the core of what we are. We call it the human animal. We’re visceral and we respond to sound and we respond to light, or we respond by panicking or having euphoria – or both! And those two, you know, can flip. It’s about that. And we’re quite considerate with the show. We’re not putting in really high frequencies, because that’s just really unpleasant. We’re aiming around here [POINTS TO CHEST]. I’m getting into chakra systems here. It’s sort of heart chakra; it’s also energy.

Are you trying to incite a sort of primal fear with the music?

JB: No – but a primal response.

PC: The best moment of any concert, whether it’s a Coil concert or any other band or even a classical concert, is the moment when you lose yourself. You become unaware of your surroundings, totally absorbed by the music. That happens less and less often with contemporary rock. I’ve been to about twenty concerts in the last two or three years and I’ve not been transported.

JB: I’ve been moved to tears of boredom.

PC: And I think that’s a shame. I think what we’re trying to do is encourage people to lose themselves in our music in the same way we lose ourselves in it. And I’ve tried that with everything we’ve ever done. Because whether you call it a trance state or a mental focusing thing – however you want to describe it – something greater takes over. And if we can bring a little bit of that to the people in the audience, then that makes it worthwhile. And it may not be necessarily something they find pleasant for that moment, but it will be something they look back on and say, "Hey, something really happened. I actually felt something."

JB: Hopefully.

PC: "And it moved me. And I can’t figure out what it was." You may never figure it out, but at least something happened.

Why I love your music: I think all music should aim to put the listener back in touch with their own imagination.

PC: Absolutely.

Obviously, most of the music that comes out today is incredibly unimaginative. However you do it, it’s amazing to me how your music almost seems impossible – that it can’t actually exist – particularly the way it can connect or click with the listener. It’s quite extraordinary. It’s a gift.

PC: I think if you connect with that place in yourself.

JB: If you’ve already got some of that in you, all we’re doing is setting the vibration frequency a little higher.

PC: But it’s not a physical… it’s not physics, necessarily. It’s some kind of emotional or psychic state that works, and I don’t know how it works. You can’t really put it on an oscilloscope and figure it out. It’s just a question of choice.

JB: It’s a question of instinct, as well.

You’ve said before that you work very instinctually. How do you mean, exactly?

JB: I have notebooks and ideas and it’s just grabbing, really: trying to be informed by the earth and the etheric. And trying, by any means whatsoever, to make that into a solid object, or a sound object, or a record. And that’s what we’ve always tried to do. It seems – we don’t create it, really. It’s already there. We just assemble a kit.

PC: We have discussions sometimes about the feeling behind a track that’s about to be started. It might be a discussion about a picture or a feeling, or a moment in a film.

JB: Sometimes we set down a whole page of parameters: it should do this, it should do that, it should reflect the moon, it should be lunar. Or we’ll burn some incense or let the dogs run wild around the room while we’re doing it – or we’ll shut them in the garden. Anything like that. Or eat carrots for a week and then do something. Just so some chemistry within us is deliberately changed.

PC: As for the music itself, it’s not like "Let’s set up a rhythm and set up a bass." We’ll try combinations of equipment or filters or computer programs almost at random and then…

JB: Something hits.

PC: There will be something about one of them that you like and you want to develop. It’s almost like the process of selection is the most important thing.

JB: This is the choice thing again.

PC: It’s hearing something that you know is right and going further with it.

Going further?

JB: When we played in Amsterdam, it was so loud, this one girl in the audience fainted because of all the frequencies. So her friends carried her outside and she had oxygen given to her. And she was asked, "Do you want to go home?" And she said, "No, I want to go back in again." So she went back to where she was. And she fainted again!

She sounds like a woman after my own heart. Did you talk to her after the show?

JB: Oh, yes. She said she loved it!

PC: Yes, and since then we’ve taken out liability insurance. [LAUGHS]

You’ve been traveling with this show quite a bit. Do you find different reactions according to territory? Are there differences between an audience in Amsterdam and one here?

PC: Not too much, actually. You’d be surprised. There are the hardcore fans that will travel five thousand miles to see you, and that’s fantastic. And then there are other people who are less familiar, or curious, or shell-shocked.

JB: We have this one guy who travels around with us – I don’t know his name, actually – and he stands centre-stage and just stares like this: [CROSSES ARMS AND GLARES]. And he comes to every one of them! And I always think, "He must be hating this! Why does he keep coming?" But in the end he comes up and gives me an assessment of the concert. He’s a really nice guy. So that’s one response.

PC: But then there are the people who come and they’re looking for your whole hidden message. They think we’re putting them in there – and we certainly have put some in there – but I think it’s quite possible to over-analyse Coil. It’s just the noise, sometimes. As simple as that.

You’ve been making music together for almost two decades. Is there any particular phase you’re particularly fond of?

PC: I always say it’s whatever we’re doing at the moment. That sounds like a cliché, but we’ve been through so many different aspects and different places. The one thing that drives me bonkers is the idea that we’d have to stay in the same place.

JB: Stasis, yeah.

PC: We’re always trying to find something new and stimulating.

And as for the future, where are you heading?

JB: Well, we’ve done Musick To Play In The Dark 1 and 2. And I think we’re going to do one more.

PC: Hmm, first I’ve heard about it.

JB: We just compiled two Russian compilations because we’ve been counterfeited so often over there. We did one melancholy one and one mad one. We took quite a bit from Musick To Play In The Dark 1, actually. I’m quite fond of it.

PC: I liked it as well. Musick To Play In The Dark takes you to that dark, melancholy, but friendly place. It’s intimate. And then, there’s our "noise" stuff that takes you to some place else – and it’s kind of a battle; not between us, but…

JB: I really like headfuck, twisted music. But I also really like introverted work, as well.

I think these two styles complement each other to give you a larger, contradictory picture.

JB: It’s a body of work. A dead body of work. [LAUGHS]

Are you going to do more along the lines of Constant Shallowness Leads to Evil?

JB: There’s one more that we’re going to do along those lines.

PC: [SIGHS] That’s news to me. Which one?

JB: Wounded Galaxies Tap At The Window, a tribute to William Burroughs.

You two are always eager to cite your influences in your music. In liner notes and in titles, a list of names come up often: Burroughs, William Blake, Austin Osman Spare, Alexander Shulgin…

PC: There are a few people, like William Burroughs or Alexander Shulgin, who had a great influence on us when we were younger. They had such a powerful effect on our lives that we feel we have an obligation to pass that on to other people, and to try to have the same or similar or as powerful effects on… not necessarily kids, but anyone who might come to us fresh. It’s a cheesy analogy, but you have to pass these things on from one generation to the next.

JB: It’s a legacy. We don’t own it, but we have our own interpretation of it. And I do think it’s a duty that we make information available. The good bits we keep to ourselves. [LAUGHS]

William Burroughs was certainly a lifer when it comes to themes that you’ve worked with: certainly the idea of hallucination as truth. Now that you’ve made a deliberate attempt to cut down on your substance use, do you ever feel you’re missing out on the "benefits" of complete drug derangement?

JB: Well, we couldn’t have kept it up, though. It takes its toll.

When does immersion becomes dangerous and self-destructive? When does it impede creativity as opposed to influence it?

JB: Well, after we completed Love’s Secret Domain, we didn’t record a lot after that, really, for quite a while. It was a long time space. Now, I’m not sure whether it’s our age or the age that we live in, but I feel far more desperate to accomplish things and make up for lost time, basically.

PC: A lot of times I just think that those experiences – those drug experiences, psychedelic experiences – that’s a place you need to see.

JB: That everyone needs to see.

PC: But you don’t need to do it over and over again. As long as you know it’s there.

JB: And you’ve absorbed the knowledge that it can give you.

PC: To continue to look back to that same door is a waste. It’s a waste of your resources.

JB: But certain things like Psilocybin mushrooms can teach you something new every time [LAUGHS].

Coil portrait courtesy of Lawrence Watson

Extract From England’s Hidden Rerverse By David Keenan

England’s Hidden Reverse is a secret history of the esoteric underground which was originally published in 2003. Based on hundreds of hours of interviews with members of Coil, Nurse With Wound and Current 93 as well as contemporaries, friends and associates, EHR illuminates a shadowy English underground scene whose work accented peculiarities of Englishness through the links and affinities they forged with earlier generations of the island’s marginals and outsiders, such as playwright Joe Orton, writers like death decadent Eric, Count Stenbock, ecstatic mystic novelist Arthur Machen and occult figures like Austin Osman Spare and Aleister Crowley. After being out of print for years, it has been republished in various formats by Strange Attractor.

The sessions for Coil’s 1991 album Love’s Secret Domain were so intense that by the end of it, the players had been brought to the point of mental collapse. Boasting one of Stapleton’s finest cover paintings, executed on an old wooden door he found in Cooloorta, it bears the motto ‘Out of Light Cometh Darkness’, and to be sure Sleazy’s memories of it are hazy at best. ‘I can remember Balance and Steve having these mad arguments that would go on for 48 hours without sleep over which sequence of words should be used,’ he recalls. ‘By that time the automation on the desk would have blown up and they’d have to start from scratch. It was pretty mad. It was worse for me as well because I was directing commercials at the same time. So I was living a schizoid life, doing one thing in the day and another at night.’

Balance remembers visions of larval shells rearing up like huge mummies in the booths. It was almost as if they’d found their way into one of the backrooms of the British Museum, as rows upon rows of 10 foot tall Amazonian warriors and Babylonian kings appeared to march through the control room. ‘I’d see them sitting there,’ Balance recounts. ‘Touching each other and talking to each other. Everyone could definitely psychically sense that there was stuff going on all the time. Me and Steve were just sat looking back into the control room at all these entities pretending to be deities and Steve said, fuck that, we’re not going in there. We didn’t come out for four days straight. I remember staring at a curry and watching moles spring out of it, but I realised I’d been looking at it so long the thing had grown fur. Four days, just too scared to go into the control room because there were all these kings sitting there, twitching.’

‘We were sprawled in a total drug-fucked daze in the lounge adjoining the studio mixing room and yes, we were visited quite relentlessly for a few hours in there,’ corroborates Thrower. ‘Whereas hallucinations of figures and faces usually flicker and come and go, these figures were proliferating and starting to crowd the room, they didn’t recede as you looked directly at them. The window through to the studio where Sleazy was mixing one of the tracks was being visited by a succession of kings and holy men. I was getting Aztec figures too, as well as some possibly Nordic people. Balance and I found that we were seeing each new figure in perfect synch with each other. As we lay there we would compare what we were seeing and there was an amazing degree of agreement, the confluence of mind was so steady. The experiences were as verifiable as reeling off the colour of passing cars together in broad daylight. It went on for ages. You would see a figure and then the other would describe it exactly, there was no question of it being the power of suggestion, we had lots of time to study what was happening and that wasn’t the answer. It was one of several experiences that cleared the way for a more inclusive mystical viewpoint for me, after quite a while spent chasing the existential zero up its own arse, which is just the mind finding endless ways of describing a dead end. This experience of the LSD sessions and some powerful later visitations led to me changing my way of thinking.’

‘My recollection of it is that most of the mixing was done at night,’ Sleazy states. ‘Our understanding of the equipment and the equipment itself was progressing so that more things were possible. I mean, Throbbing Gristle were basically guitars and tapes, with me and Chris Carter having to actually build any electronics from scratch. How Coil actually sounds is often a function of the state of technology at that time. So a lot of the more freaked out tracks on LSD are that way because we wanted them to be but also because there were advances in technology that would take the sound to places where it hadn’t been possible to take it before. We took in a lot of our experiences in clubs, certainly, but LSD was much more about the places that you went to when you were at these places.’

More than drugs, what LSD is most influenced by is England’s lunatic tradition – that is the English underground in all its sexual, cultural and artistic variety. On LSD, Coil drew on the art and lives of outsiders and visionaries like Charles Sims, Derek Jarman, Austin Osman Spare, Joe Orton and William Blake, factoring them into their psychedelic gazetteer of England’s hidden reverse.

‘The place where we were mixing it was in Bloomsbury,’ Sleazy explains. ‘In this weird basement and we would pass the British Museum and many of the song’s influences were from that tradition, I’d think of Nic Roeg’s film Performance or The King Singers, examples of eccentric English culture or English culture that was perverted or bent, so the environment seemed to refer to it.’ Charles Laughton, the English born actor who starred in Mutiny On The Bounty and played Quasimodo in The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, before going to make The Night Of The Hunter (1955), his only film as director, is another of LSD’s alternate touchstones. The Night Of The Hunter’s rogue preacher character, played by Robert Mitchum, provides the spoken part on ‘Further Back And Faster’, a psychotic electrohymn to temporal displacement. ‘He’s another example of an English eccentric who is successful creatively until people get scared,’ Sleazy points out. ‘There’s a repeating thing here isn’t there?’ ‘Before he died in Hollywood, he ended up in Whitby, where Dracula enters the UK in Bram Stoker’s novel,’ Balance concurs. ‘Living with a 15 year old boy in a boarding house. Trying to live his own life. Blake is also very important to me but I think he’s so misrepresented, he’s become this caricature of a visionary artist, living with his wife and seeing angels in the apple tree.’ It’s vaguely surreal to witness Blake’s headline status at the Proms, a jingoistic celebration of the figments of empire. With the title track’s act of reversal, Coil restore Blake’s true rebel status.

‘I don’t think these kinds of artist are specifically and intentionally excluded,’ Sleazy states. ‘If English culture was able to circumvent the kind of minor embarrassment and hesitation which causes it not to embrace the underground artists of which we consider ourselves a part, then there would be a much more complete embracing of this kind of culture because this is what Britain really is. Generally English culture nowadays is dull because a few people in the media have a sort of squeamishness about them and are just unable to take the last step with us. If Britain in general could overcome that last hesitation we would be a much more potent artistic voice as a country because all of the truths that these kind of artists espouse would be accepted. I would consider us as part of some kind of general English esoteric tradition although I don’t think necessarily that English people have the copyright on that particular thread. There are lots of people, Americans like Burroughs, for instance, whom we’d consider part of the same movement, but I think English people are pretty good at it. English society has such a culture of eccentricity, like the village idiot or the wacky professor and English people who put themselves in this position in public haven’t suffered the same ignominy and abuse that eccentrics tend to suffer in the USA, for example.’

Following on from Blake, Coil connect with the psychogeography of London’s terra incognita – secret places, mystic alignments, old buildings hidden away beneath the modern. Tracks like LSD’s eerie instrumental ‘Dark River’ and Black Light District’s ‘Lost Rivers Of London’ – its title taken from Nicholas Barton’s book of the same name that traced the trails of the Fleet, the Tyburn, Stamford Brook and Walbrook beneath the pavements of the capital – are attempts to map the secret city. ‘If London still has any magic that’s where we find it,’ Balance maintains. ‘It exists somewhere else really. It’s one of the few reasons I can tolerate it. It’s been a sacred place for a long, long time. One of the reasons I like Spare so much is that he’s a London artist. Although when he once claimed to be the reincarnation of William Blake he was obviously being tongue-in-cheek, he certainly saw himself in that mystic tradition and I see ourselves as being like that. Me and Tibet more so, we read these things and we immerse ourselves in it.’

Sleazy warms to the theme: ‘Whenever you find a culture that has strong regenerative music it’s always a culture that has a tradition of mysticism and mystic individuals. I’d have to say, though, for me there’s no difference between chemically altered states and magic. Psychedelics specifically. It opens you up to something that objectively exists. Well, all experience is subjective, there is no other kind, but the places that you go to with those drugs are just as real for you as… Croydon.’ Balance takes up the thread: ‘I mean, these places have been accurately mapped by certain people, including John Dee. Certain people can access these areas, like Amazonian shamans, Terence McKenna, certain people. Some people, using their ‘maps’ precisely, will go to the same place and have comparable experiences – the equivalent of geographical regions. You go there and you see what is there.’

Love’s Secret Domain remains one of Coil’s most lucid glimpses of the other side. With the help of co-producer and engineer Danny Hyde, Coil took the new dance music and subtly altered its DNA, re-configuring it as concrète punk. Sleazy jokingly describes it as ‘the party album’ and there are a couple of incongruously straight techno sides, like ‘The Snow’ and ‘Windowpane’ that leave you scratching your head. Balance, however, still loves it. ‘Certain people don’t like it because it’s got socalled ‘disco’ elements on it,’ he smiles. ‘We never considered it disco, we weren’t trying to do House or dance… no way. We started listening to a lot of dance music but we wouldn’t let it in to the records at all. It was, like, hermetically sealed off. Eventually we let it in on Love’s Secret Domain but we weren’t trying to do dance music.

‘That whole rhythmic thing is moronic, totally moronic,’ he contends. ‘We intended these records to be psychoactive – to be music to take drugs by. The title and everything points to that… how obvious could we make it?’ What separates Coil’s use of rhythm from mainstream dancefloor music is that on the whole the beats don’t lead the track – they’re another background texture, spiralling chaotically inwards. At points there is so much blurred movement that it almost sounds like an aural action painting. The album features guest vocals from Annie Anxiety, Rose McDowall and Marc Almond. Ex-This Heat drummer Charles Hayward adds the frenzied percussion to ‘Love’s Secret Domain’ itself, as Balance pierces the veil and England’s black heart stands exposed; ‘O rose, thou art sick!’ It functions as a damnation of the rotten state of British culture, a celebration of perversity and a Blakean call to arms.

Order a copy of England’s Hidden Reverse from Strange Attractor