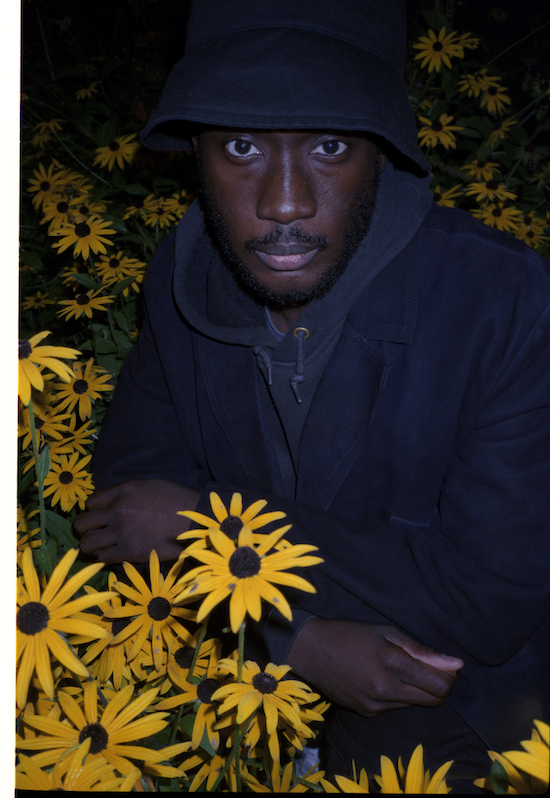

Photos by Ksenia Burnasheva

“I hope for this record to be an inspiration in terms of being able to enjoy and see the value in dreaming”, Coby Sey says whilst looking into the distance, as I ask him of his hopes for his debut album Conduit. “Not necessarily in a clichéd ‘chase your dreams’ way, but embracing various emotions and lightness and darkness, and not seeing them just as positive and negative. The album is also a documentary response to the world around me.”

Though calm and measured, Sey’s excitement about Conduit’s forthcoming release is palpable. He often thinks long and hard before he answers a question, owing to the conceptual and holistic nature of his work, and wanting to ensure he says what he means. The album is his first cohesive project that provides us with a glimpse into his world. Written before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, the aftermath of Brexit and the 2021 London mayoral election, Conduit is a politically charged and self-examining response.

The album strikes a balance between lyric-led tracks like ‘Permeated Secrets’, which allow Sey to demonstrate his poetic diction in an uninterrupted stream of consciousness, and instrumental-led tracks like ‘Eve (Anwummerɛ)’, that favour sound design to create a landscape representative of the world he sees and experiences. Conduit varies in both in cadence and sound from track to track, in one realm unsettling and foreboding, and in another serene in its composition. Throughout the album, there is a distinct call for social change, and for the mobilisation of marginalised communities.

Attributing Sey’s sound to a particular genre proves difficult. It has been referred to as ‘post grime’, though this term seems to have appeared from a vacuum; defining it proves just as elusive. The essence of Sey’s sound is a fusion of his influences – whether it be post punk, dreampop, grime, hip hop, jazz, rock or dub. They have amalgamated in many forms to create Conduit, and the singles that came before it.

Conduit is orchestrated to be uncompromising, and not to address “binary positivity and negativity, but instead use the shades in between,” Sey says. With ‘Night Ride’, the abrasiveness of its repetitive nature is a mechanism to convey some kind of truth, to awaken the passive listener into action, an element of artistry Sey has always aligned himself with. “Loads of musicians I have grown up listening to and admiring, for example Public Enemy, a lot of their music with Bomb Squad is noise and it’s abrasive but there is a rawness to it and there is a truth to it. That speaks to me. Miles Davis’ sound during the 1970s, Liz Harris who releases music as Grouper, Sonic Youth… there are a wide range of musicians who have demonstrated this to me and I feel a kinship.”

The Lewisham-born artist has been working on Conduit since 2017, and his upbringing played a significant role in shaping the artist we see today. He speaks fondly on the place that raised him, and how its history is central to the sound he emits. The album’s sonics, production and delivery are atypical of what you’d expect from an artist from South London. That is its strength. It will no doubt unsettle many, however it carries with it a greater purpose than that of an easy listen. Conduit pulls no punches when exploring the current state of politics, and being a voice for the voiceless.

Given that you have released a few singles over the years, why now do you feel it’s time for an album?

Coby Sey: One of the answers is because I have a bit more time to do it now. I’ve wanted to create an album for a very long time. Making albums is a way of telling or presenting stories, and I feel creating an album will provide the space for me to do that at the length that I’d like. This comes from growing up listening to albums, really enjoying them and being really into stories whether it’s in the form of music, books, or video games; music is my medium of being able to convey that. The story doesn’t necessarily have to be presented in a way that’s super conceptual, but it can be conveyed through the sonics and feeling within the record itself. I strongly believe the narrative can be presented in that way, and doing it in the way provides space for whoever is listening to figure out or make up their mind as to what the narrative could be when they apply it to themselves.

Is being from Lewisham and South East London central to your sound?

CS: I think it is to an extent. It’s definitely played a key part in who I am and my outlook. It’s of resilience, it’s of unity. It’s multicultural: a genuine melting pot of people of various classes, heritages and cultures; Black, White, Brown, ESEA, MENA, etcetera. My grandparents moved from the eastern region of Ghana to South East London in the early 1960s. Lewisham has a well-documented history of groups congregating there (ALCARAF, British Black Panthers) to oppose racism and fascism from far-right movements. About 4000 anti-racist activists took it on themselves to oppose and counter march the racist far-right marches, which led to The Battle Of Lewisham in August 1977, which I’m proud of. Darcus Howe, Roger Godsiff and more were present and gave speeches. I thought about the New Cross Fire incident in 1981, which my maternal uncle is connected to. Some of his close friends were lost to it. He left the house party much earlier before that arson attack because he had football the following morning. I channelled all of this and recent events into a song from Conduit named ‘Dial Square (Confront)’.”

There is an element of frustration in your sound, and sometimes words drowned out by sound as if to suggest you are unheard. In your lyrics, you often reference communities that are marginalised. Is Conduit, in essence, a voice for those communities?

CS: Yes, with Conduit I definitely felt it was needed for me to be more upfront. Especially given that I did grow up in Lewisham and have a working class background.

Even though I started working on Conduit in 2018, I worked on it on and off because I was working a full-time job to make ends meet. By the time I was nearing completion the 2021 London Mayoral elections were happening and that was when I started working on ‘Onus’. It was the last song I worked on for the record, and this was in the midst of the Covid-19 outbreak, still with that sense of uncertainty and a slow response to the pandemic. It involved the continuation of finger pointing towards those communities who were marginalised but still were on the frontline looking after us all. I couldn’t not talk about it or not address it.

For ages, my excuse would be “action over words”, but there comes a time and a place where we just have to say it how it is. That doesn’t mean that I can’t or shouldn’t compromise in terms of how I’d want to say it or how I interweave that into how I make music. It was key to find a balance in a way that I can do both.

You’ve said that your work isn’t to address binary positivity and negativity, but to use the shades in between. When you refer to more nuanced, complex feelings that would otherwise be difficult to express, is that where your sound takes hold?

CS: 100 per cent! Take for example, what people often categorise as ‘noise’. For me, it is abrasive but listening further and further I can hear something else. There’s a soulfulness in there. I think there are a wider palette of emotions that can be explored through sound and music. I definitely credit my older brother Kwes as well as Mica Levi and loads of other people for helping me to understand that. They may not have necessarily told me this directly, but just from the music they’ve made and having conversations with them about music and musicians.

There will be people who see your sound as unsettling, but it is designed to confront. ‘Response’ in particular is mostly foreboding instrumental noise before it divulges into repetitive calls from you designed to antagonise the listener, like a rallying call. What was your intention behind this track?

CS: ‘Response’ is the storm of the record, like the lightning bolt of the album. I did a bit of keyboard over-dubbing afterwards, but the majority Response was recorded live with three other musicians and those words at the time just seemed appropriate. It was recorded a year after the referendum in 2016. Even though I wrote those words about relationships, when I listened back to them it felt like it could be me talking about Brexit. But then in the context of the record, it felt like it slotted in with the themes.

‘Response’ was about capturing that moment. There were no rehearsals for that particular song, we did the jam there and then. Within the context of the record, it feels like an accumulation of all of these mixed thoughts and feelings, and then boom! This is the section where the confrontation happens and let’s see what comes out as a result. Following on from that is ‘Eve’, where the calm has arrived after the storm.

What do you see as calm in the context of Conduit? Is that the solution, where we have arrived in a socio-political landscape that benefits the working class?

CS: Calm is not only a state of mind but also a sense of trust. It’s doing things without feeling forced. It’s a strange a paradox, calmness requires work but the idea of the calmness is something difficult to attain. Maybe one day calmness can be synonymous with peace and being content – but to be content isn’t to be ignorant about situations but to acknowledge them and everyone else and the perspectives that they come with. I suppose this is what calmness means to me, but it may not be the same for others.

You’ve referenced yourself as having ‘post grime’ allegiances before. What does post grime mean to you?

I notice there have been write ups about ‘post grime’ in relation to me. I grew up on grime, the likes of Kano and D Double E, so I understand what it means. When I heard the term post grime, it made me think of post punk. Post punk was after punk, and in what I have read there are always comparisons between grime and punk in terms of its roots and it being a response… people doing things themselves in a DIY manner. Kicking down the doors because the doors were being shut in their faces.

Personally, ever since I have made music I have always been hesitant to categorise myself – it’s all connected. But if [being referred to as post grime] helps provide context to my music then I’m okay with it. But I am definitely keen to mention that my sound is about music and it’s not genre specific.

When I was listening to a few of the songs on Conduit, I got this feeling of stillness but being amongst incessant movement, like being on a train moving without direction. To what extent does being aware of what is happening around you, versus a desire for stillness to comprehend what is happening, influence your writing style?

CS: I like that observation! I like to think of my music as allowing the possibility of drifting through different forms of consciousness, i.e. being present in the moment but also on another dimensional plane of consciousness that we may not hear but you can feel on an instinctive sort of level. I try to convey that within my music, not just Conduit but throughout.

Is that why you chose the name Conduit? The album as mechanism to take the listener from one plane of existence to another?

CS: In a way that’s true. But I like to think there is room for listeners to translate sounds so they align with them. I think that’s the great thing about making music, it allows invitation for another person’s to dial into their imagination when listening to it. But I’d definitely be lying if I didn’t acknowledge visual elements that I’m aiming to convey.

A big part of what I like doing is in the lineage of dub music. My mother would play lovers’ rock tunes and I heavily got into dub music during my late teens, which was also at the time of the dubstep movement. The older dub stuff, that was psychedelic and transcendent. Also the music that is categorised as dream pop, like Cocteau Twins, for me they’re really key artists that I’m hugely fond of and have helped me to figure things out sonically and find my voice.

The soundscape you depict is very visual, what did you seek to depict with ‘Permeated Secrets’?

CS: Definitely a landscape, which goes back to the idea of lightness and darkness, and those tones and shadows in-between. I wanted to use the monochrome-ness [in the video] to help convey those lands. It was my way of beginning to look inwards to then look outwards. I wrote the first verse before the pandemic and the second verse during the pandemic. In terms of the instrumentation, I went through multiple different versions until I got to that stage. When the pandemic hit, I found the words I wanted to say for the second verse which is more abrasive – I mention the pandemic, I mention trust and the idea of finger pointing. Initially the video was going to be in colour. But having it in black and white helped accentuate the words.

Noticeably compared to my previous releases, the verses are quite long and dense. I felt it needed that, that I needed to use a stream of consciousness. I tend to approach writing from a poetic angle, but I just felt the second verse needed me to say things as it is. Especially with the pandemic, I immediately understood the trepidation and hesitancy that was occurring, because there is history of governments saying one thing and doing the complete opposite. One of my concerns with the pandemic was not so much about the validity of the virus, I definitely believe it existed. It was more to do with the restrictions, especially with the current government, that they could be used as a way to push through laws that could risk people’s basic human rights and speak up and say things. Two instances I can think of are the Black Lives Matter protests and Sarah Everard protests. I had written ‘Permeated Secrets’ in between those two protests and my concern was our rights to speak up on these issues, that the lockdown should not be an excuse to usher in new laws that restrict us. I want people to be able to speak up and say things need to change. Since then the government has attempted to push agendas like the Nationality And Borders Act which I personally find to be of huge concern. ‘Permeated Secrets’ was my way of speaking out against these things.

In your lyrics, you say, “I don’t care if you like my work, in freedom there is a distinction”. Are you more concerned about what your work does as opposed to whether or not it is liked?

That was in the heat of the moment whereby I was voicing feelings that if my freedom is not valued or seen as something to be valued, or there isn’t equality in everybody, then my opinion of that person is of no concern. I don’t even think I can have a conversation with someone who isn’t into the idea of there being equality for everyone. I feel like there can’t be a conversation had if they feel there should be a hierarchal allocation of equality.

What are you looking forward to most about the response to your first cohesive project?

CS: I definitely look forward to seeing and hearing how people interpret this record. It is an accumulation of things I grew up absorbing, things I’ve seen and listened to. Works of art, but also seeing poetry in the world around me. I find the perception intriguing because releasing something to me is a way of starting a dialogue or initiating conversation not just about the work but also about the response to the work. Being able to be transported without needing to take any substance to do so – that’s huge for me.

Coby Sey’s debut album Conduit is released on 9 September via AD93