Talking Head and Tom Tom Club founder Chris Frantz’s Remain In Love, published last month after the pandemic delayed its planned May release and scuttled his planned promotional tour, was one of this year’s most anticipated music autobiographies.

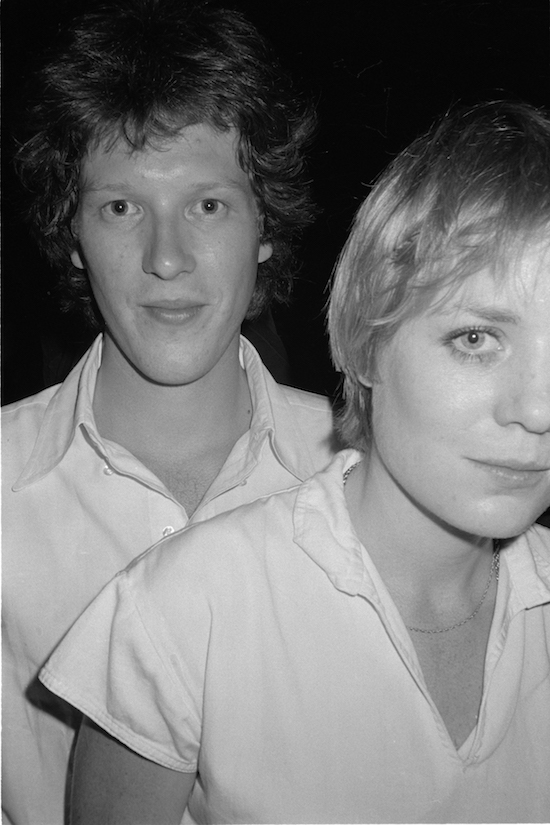

I first met Chris and his wife and musical collaborator Tina Weymouth on a snowy winter’s day at a Manhattan record label office in the first month of the new century. I had completed my work supervising the DVD premiere of the classic Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense a couple of months earlier, and they came by my desk to introduce themselves after a meeting with other label people. Their warmth and good humour were immediately apparent, and we spent much of the conversation talking about the joys and travails of raising sons.

Chris had almost entirely refrained from speaking about Talking Heads’ interpersonal dynamics since the band broke up in 1991, but he felt that “some things needed to be said” and curiosity is understandably high as he takes this opportunity to tell his story.

Meeting Tina Weymouth and David Byrne at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1971 was a big moment in both your romantic and musical life, but when you were later introduced to Patti Smith she dismissed you as middle class art school kids. Were you treated differently by others in the downtown New York scene who maybe saw you as fey or not street enough?

Chris Frantz: I don’t know that they thought we were fey, I think it was more of a degree of unfamiliarity they had with people like us. Many of the kids down at CBGB hadn’t gone to college and hadn’t travelled very much, they’d travelled to New York from wherever they were and that was about it. They probably viewed us with a kind of reverse snobbery, but I never felt troubled by that as it wasn’t very serious.

That was Patti Smith’s personality at the time, snapping gum and firing off barbs. Patti’s barb for me when I was introduced to her by her lovely guitar player Lenny Kaye was, “Oh yeah, you’re those art school kids, I wish my parents had been rich enough to send me to art school” and then she turned on her heel and started talking to somebody else. I thought, “Really, you don’t have time for people who went to art school? What about Keith Richards?”

When you, David and Tina started playing together, you were the most competent musician of the three of you followed by David, who had been in a couple of student bands, and then Tina, who had played some folk guitar but had never touched a bass. I don’t get a strong sense though that despite initially being the ‘best’ musician that you assumed the role of bandleader, why was that?

CF: Actually, I invited David to join an as yet uncreated band, and it was my idea to invite Tina to join the band. Later I invited Jerry Harrison to join us after the break-up of Modern Lovers, whose bass player Ernie’s aunt was a friend of my mom. David and Tina both agreed that Jerry was a great addition as it was obvious to all of us that he was the right guy for the job. It was me who would speak to Seymour Stein (their label boss), and it was me who would say, “Hey, it’s time we should make another record."

This of course is all behind the scenes. In front of the scene everyone sees this crazy looking dude with a microphone and a guitar and as usual everybody says, “Oh, there’s the leader of the band”. Perception is a funny thing, isn’t it?

We were a full on working collaborative, everybody did their job and did it really well and I have no complaints about any of it. Everybody had a really strong work ethic and got along really well. There’s a lot of irritants that come from the outside when things start to get bigger, with more and more people whispering in your ear about things, or in the case of the British music press, blasting across the front page of the NME or Sounds.

Did you and Tina ever experience a ‘Eureka!’ moment when you came to the realisation that you’d become a powerful rhythm section, a moment that felt like a goal had been achieved?

CF: I can remember feeling great relief during the recording of our first album, and actually after the recording of every album, when I listened to a playback of a basic track and it sounded really good. I’d think “Thank God it sounds good because he can’t play it any better than that, I hope the rest of them like it!” I was never the type of musician, nor was anyone in Talking Heads, who was a session player type musician.

Our goal with Talking Heads was never about making hits, although it felt really good when we finally did have a hit and when we had marvellous critiques in the press. Our real goal, as Tina said to American Bandstand host Dick Clark when he asked her what our ultimate ambition was, was to “make our mark on music history”. As Bob Dylan and The Beatles and The Beach Boys had done before us, we wanted to create something that had some musical historical significance.

CBGB has acquired a kind of mythical romantic aura from a distance of four decades but the club’s literal filthiness (dog shit everywhere, abominably gross toilets) and location in the midst of the Bowery, which in the book you vividly evoke as an urban nightmare straight out of Taxi Driver, seems hard to reconcile with the all the incredibly forward looking music being played in that little dive bar.

CF: Funny you mention Taxi Driver because that movie premiered my first summer in New York, and I went to see it and thought, “Oh my God what have I done, I’ve moved right in to this!”

It was a crazy time but it was so artistically fruitful, there was so much going on in downtown New York then despite the danger and the filth. I can remember a day during a garbage strike during the summer when it was really hot and when it gets hot in New York the kids open up the fire hydrants. I walked out of our building and there were piles of flaming garbage floating down the street that the kids had set on fire and I immediately thought, “Am I losing my mind, where am I!?”

One night Tina was threatened by a gang of teenagers who ultimately left her alone, but other than that we very fortunate to never be mugged or robbed or anything like that. Later after we moved to Long Island City somebody broke in to our place there twice and stole guitars but I think that was an inside job by somebody in the building.

The Bowery was very motivating, because living in that environment made us want to do something great so we could get the hell out of there. CBGB was a dump but there were great people working there, particularly Hilly (Kristal) the boss. By 1976 we could make our month’s rent playing one weekend at CBGB, which felt like quite an accomplishment: our rent was $289.

Is there a night or a weekend at CBGB that stands out for you as the most memorable?

CF: Fast forward to 1988 when Tom Tom Club had our album Boom Boom Chi Boom Boom coming out and we played a 15 night, three week residency at the club. There were lines down the block. At the end of each week we had a special guest who joined us on stage at the end of the night. The first week it was Debbie Harry, who got up with us at the end of the night and sang the Velvet Underground’s ‘Femme Fatale’ that we covered on the album, and the next week we had Dee Dee Ramone get up and play guitar on ‘Psycho Killer’. During soundcheck Dee Dee said, “Man this song is really hard!”

The final night of the 15 night run our special guest was Lou Reed. Lou had played on our ‘Femme Fatale’ cover on the album so I called him up and asked him if he would come down and play, and I don’t think he’d ever performed there. He agreed to do it if we’d send him a limo so I sent him the biggest limo we could afford.

Lou pulled up in front of CBGB and stepped out of the limo, the seas parted and he walked in and got up and played ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’, ‘Sweet Jane’, and ‘Femme Fatale’. It was a really hot night and the amps for the monitors were overheating and were cutting in and out. The crowd went nuts. That’s my most memorable night at CBGB.

Talking Heads rebuffed the first serious attempts by labels to sign you because you felt that your music wasn’t ready to record yet, but was your reticence also due in part to an understanding of the machinations of the industry and the impact that signing prematurely could have on a potential career?

CF: We’d heard cautionary stories from people involved with the music business, and I’d read a lot of rock & roll biographies. We didn’t have any management and we knew it was important to have a seasoned veteran basically telling a record company what to do. We’d heard about bands who rushed to make a record which didn’t turn out great and who never had a chance to make another one.

We had made a few demos with a guy named Mark Spector from CBS who took us in to the famous big studio where Dylan had recorded at CBS Studios in New York. We made some very quickly recorded live demos which we enjoyed listening to but didn’t sound like a record you’d want to listen to time and time again. We realised we needed to spend some time honing our stagecraft and we were thinking it was time to find a fourth member to fill out the sound, because the sound of a trio is pretty sparse.

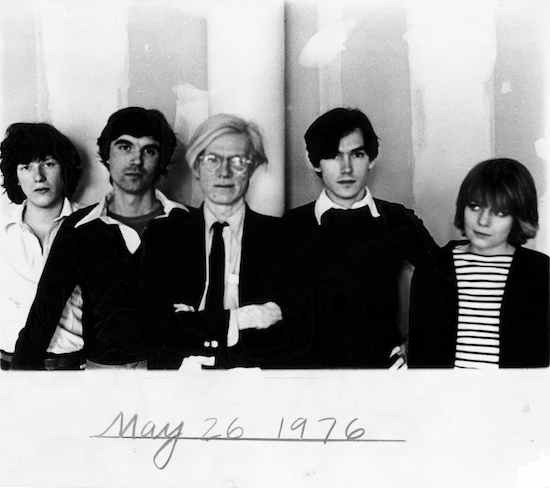

Seymour Stein of Sire Records was a guy who kept coming back and coming back and had offered us a record deal the first time he saw us down at CBGB. He came to our loft on Chrystie Street the day after he first saw us and we told him we weren’t ready yet, but if he could sit tight one day we’d come back to him. 18 months later on 1 November 1976 we signed a deal with Seymour.

We didn’t have that many other options but we had a few. Seymour had signed the Ramones and I spoke to their manager Danny Fields and asked him what Seymour was like and if he was doing a good job for them. Danny replied, “Well Chris, you know no record company is perfect but Seymour has always done alright by us”, and that was good enough for me. We also liked the fact that Seymour’s offices were in a brownstone on W74th St near the corner of Amsterdam Avenue. He told us we could come in and talk to him anytime and we thought that was a lot better than dealing with some guy on the top floor of Blackrock, the CBS building.

Going with Seymour worked out well. He made a deal with Warner Brothers and remained kind of independent while having access to Warner Brothers’ promotion and distribution.

And Lou Reed had tried to sign you.

CF: That was very early on, after I think only a few performances. Lou came down to see us and he loved it, and invited us back to his apartment to chat after the show. We packed our equipment and took it back to our loft and splurged on a Checker cab to go uptown to Lou’s apartment, which we were surprised to see was practically across the street from Bloomingdale’s.

Long story short he offered to produce our first album and of course we thought, ‘WOW! Lou Reed wants to produce our album.’ Lou asked us to meet his manager Johnny Podell and said that he would work everything out. A day or two later we had the meeting with Johnny Podell, who was also a big agent at the time and had an agency called BMF, which stood for Bad Mother Fucker. We sat down with him and he was doing some blow which he offered us but we said no thanks, and he gave us some sort of agreement. We looked at it and thought that we’d better consult with a lawyer.

We decided to contact an attorney named Peter Parcher who was well known and was in the papers at the time because he had just got Keith Richards off after his major heroin bust up in Canada. We called Peter and he told us to come to his office and he’d introduce us to one of his associates. We sat down with Peter and one of his partners, Alan Shulman. Alan took one look at it and said, “I would never allow one of my clients to sign this. This is a standard production deal, and it means that Lou Reed will pay for the recording but then he’ll own it. If you have a hit, he’ll make all the money and if he wants to sell it to Joe Schmo Records in New Jersey, he can do it."

He told us this kind of deal was the reason that so many r&b artists from the 50s didn’t have a pot to piss in, and we said, “Oh, we see, is there any way we could negotiate a bit?” Alan said, “If they gave you this agreement I wouldn’t bother even trying to do anything.” I don’t know if it was Lou’s idea to give us that agreement or if it was Johnny Podell’s or if they conferred about it, but we remained good friends with Lou until his dying day, although we never did any business together.

Johnny Ramone was a particularly churlish customer, yet it’s clear that you and Tina found humour (most of the time) in his boorishness and closed-mindedness when you toured extensively with the Ramones. Is there such a thing as a Johnny episode that you remember with fondness rather than bemusement?

CF: In 1990 or 1991 we did a tour called ‘Escape From New York’, which featured Debbie Harry and her band, the Ramones, Tom Tom Club and Jerry Harrison. We all travelled in tour buses except for the Ramones, and we were covering some huge distances as it was an American tour. The Ramones were still travelling in a van because Johnny was controlling the purse strings and he made sure they had more money at the end of a tour by travelling in a van rather than renting an expensive tour bus. I don’t how they did it but the poor Ramones would arrive at shows having slept sitting up, and all their food would have come from convenience stores and places like that. Johnny was a really hard taskmaster for the band and he didn’t let up, and later in their career he was still the same.

An unexpected thing that happened on the tour was that Johnny became kind of friendly towards us. We were getting good pay cheques which I think made him feel friendly, and he even signed my tour jacket at the end of the tour like everyone else did. I blame his father for Johnny’s bad attitude. He was just plain mean to so many people, and while Johnny evidently had a sweeter side we rarely saw it.

Can you tell me about the creation of a Talking Heads classic to illustrate how the band’s creative dynamic worked: how about ‘Once In A Lifetime’?

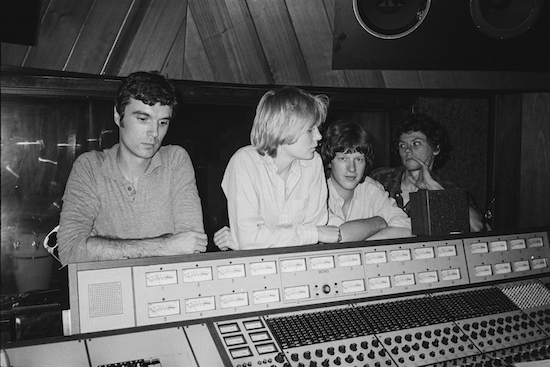

CF: We were down at Compass Point Studio in Nassau, and the song was written in the studio like all the other songs on Remain In Light. Our engineer Rhett Davies who’d done a lot of work with Eno and engineered More Songs About Buildings And Food announced that he was leaving just as we were about to start work on ‘Once In A Lifetime’. Of course I asked Rhett, "Why are you leaving?” To which he replied, “Because every time you come up with something that sounds like it could be a hit Brian Eno says it’s no good!” I pleaded with him to stay but he insisted he had to go.

So we got this young Jamaican guy who was a resident engineer at Compass Point named Steven Stanley to take his place. I think Steven was just barely in his 20s at the time. We asked him to record the basic tracks while we waited for another engineer to come out from California, and Steven did a fantastic job.

Tina and I went in to the studio and worked out a rhythm, and we were sort of like a human loop because we didn’t have samplers then, so we played this loop, de nah nah nah, de nah nah nah, for like eight minutes. Then David and Jerry joined us and added guitar parts or keyboard parts after it was decided that our part was good and up to Brian Eno’s standards of excellence. As I recall most of Jerry’s keyboard parts, especially that human arpeggiator sound that the song begins with, were played in the control room later. I remember Jerry talking about the organ that comes in later in the song and saying, “I’ve always wanted to play that organ part from the Velvet Underground’s ‘What Goes On’ and I think it works at the end of this song”, and it did work, magnificently.

David and Jerry did their guitar parts but there were no chord changes. They created a loop much like our rhythm loop that would run throughout the whole song. So they went back out again and added another, different part so that you could switch between the two in the studio and create a chord change or a verse/chorus like pattern.

By the time we’d recorded all the basic tracks we still had no lyrics, zero. We’d been on tour a lot and none of us were ever any good at writing songs while we were on the road. We knew we had 10 or 11 extraordinary basic tracks, so David said he was going to take some time to come up with lyrics that were as good as the basic tracks.

We went back to the US and I believe what happened was that David rented a car and drove around parts of the US listening to the radio. In the case of ‘Once In A Lifetime’ he was inspired by the Southern Baptist preachers that are heard on AM radio on a Sunday morning, all that fire and brimstone.

‘Wordy Rappinghood’ is one of those songs that was created in a manner akin to a chemical lab accident or spontaneous combustion – a number of seemingly incongruous elements merging and creating something fresh and unique. How did all of the elements come together?

CF: At the end of the Remain In Light tour, because we’d had such a big band and crew to go with it, there was really no money left. David and Jerry got money from Seymour Stein to make solo albums, and our manager Gary Kurfirst went to Seymour and said that “Chris and Tina need to do something too”. Seymour told Gary he couldn’t afford three Talking Heads solo albums, which kind of hurt our feelings but I guess was understandable.

Gary then went to see his old friend Chris Blackwell at Island Records and Chris invited us to return to Compass Point Studios and record a single. Chris agreed to finance an album if he liked the single, and we jumped at the offer as it sounded perfect. We met with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry to discuss producing us, but after he agreed to do it we eventually realised we were barking up the wrong tree with Scratch as much as we loved him.

We returned again to the young Jamaican engineer Steven Stanley, who was like a young version of Scratch. Tina and I recorded the drums and bass and then we called up the Bahamian guitarist Monte Brown who had played in the funk ensemble T-Connection. Monte played that nice rhythm and picking part. Tina had written the ‘dee-da-dee-da-da-de-da-da-dee-da-dee’ part and some other things all of which combined to create a sparse but really cool basic track. Tina was stressing about the vocals until I told her there was a new thing called rap, so she could just rap and didn’t have to sing!

Tina then came up with the idea that she’d write about words and how they’re used for good and for bad, but we still needed a chorus. Tina and her sisters Laura and Lani, who had come down to Compass Point at our invitation to sing with her, were walking to the beach when Lani suddenly remembered a playground chant from their childhood: a ram sam sam, a ram sam sam, kuni kuni kuni kuni ram sam sam etc. When they got back to the studio they told us there was something they wanted to try, and Stevie set up the mics and pressed record. The girls sang the chant and we were like “HALLELUJAH!” It sounded completely different from anything else you were hearing and it was just perfect.

We invited Chris Blackwell in to hear it as he was the arbiter of whether this single was good enough for a commitment to make an album. While Chris listened to a rough mix of the song he was beaming and he told us he loved it. He released it as a single in Europe and Latin America while we got to work on the rest of the album, and while we did that the single went Top Ten in at least seven countries in Europe.

Looking back on Talking Heads from this distance and after having spent a couple of years writing your life story, do you think there’s more the band could have accomplished?

CF: Witness Bob Dylan’s latest album which most people agree is phenomenal. It took him something like eight years to write and record and harkens back to his best work. Even though we were approaching a certain age I think we still had it in us to do something good, in fact I’m sure of it.

Around the time that David sneaked out of the band our manager had negotiated a new agreement for Talking Heads and part of that was that we’d have our own label. This would have been interesting because we could have brought in bands that we loved or artists that we discovered and record and produce them. David kind of took that away from us too and it became his Luaka Bop label. I had had high hopes for that idea, and we’d had already some producing success with Ziggy Marley and Shirley Manson, but it wasn’t to be.

Tina and I also had an idea that if we did start making the kind of money that say U2 or REM eventually made, we’d create an artistic foundation and we’d become patrons and give grants to artists. In America we don’t have really have those. I was told that the Viennese Opera House had a budget given to it by their government that was bigger than the entire amount given to the arts by the United States government.

You were very circumspect in saying anything revealing about David Byrne for many years, but you’ve become noticeably less inclined not to talk about him frankly in more recent years – what’s changed for you in this regard?

CF: I think it’s unlikely that there will ever be a Talking Heads reunion. David has been adamant to me and to other people that that’s not going to happen. Despite the fact that our last album was released in 1991 (29 years, holy mackerel!), I still hear Talking Heads all the time on American radio and in the supermarket and read retrospective pieces in the press. Talking Heads is clearly still important, so I thought that maybe I should give people my version of what happened because I was there. So many pieces I see are basically just regurgitated from the 1978 NME or something like that.

I felt that there were some things that needed to be said, and I also felt that there are some things that I did not need to say – I didn’t tell you everything. I’m very fortunate in that I can still remember things and knock on wood let’s hope that continues because people my age forget stuff. I don’t want to forget.

Of course Talking Heads is a big part of this book, but an even bigger part is Tina Weymouth, she’s the hero of the book. David, as wonderful as he is, is just one of many interesting characters in it.