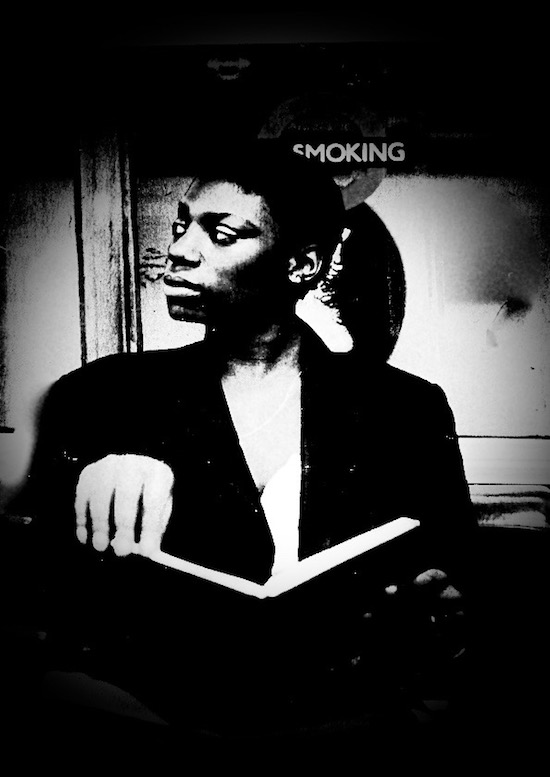

Vocalist Chas Hines is only just getting to speak at length in public about her experience in the group Bona Rays – some 40-odd years after the fact. The group formed in 1978 round the core of Hines and guitarist, Tony Keating and were one of the first black, female-led British punk groups. They were responsible for just two singles but it seems clear that now that their work was revolutionary – ahead of a steep curve.

‘Poser’ and ‘Getaway Blues’ – though only heard by a handful of people up until now – still crackle with poise and intensity, a sound born out of Kentish Town’s Ingestre Road Community Centre. Black-British, of West Indian descent, Hines involvement with Bona Rays should always have been a fundamental statement in the global history of rock music… so why does nobody talk about them being one of the first black female led punk bands in Britain?

Hines joined Bona Rays while she was still 18. Her style was more instinctive than tutored: “I always wanted to be in a band, ever since I saw Fleetwood Mac. They taught me that girls could be in bands and be cool. I just knew I wanted to do it – there was no question in my mind. And it was pretty much straight after school I joined Bona Rays.”

She was incredibly ambitious for a teenager, if still typically impressionable, and had her eye trained on the music industry early on. She says: “I was on my way home from a gig at the Hope and Anchor in Highbury and Islington. I remember seeing a brilliant poster on the tube platform, so I climbed across the tracks in order to tear it off the wall. I remember singing to myself because I always loved the acoustics in the underground. Some guy came over to me and said, ‘My friend would really love you. You should audition for the band he’s looking to set up.’ The following week I went to meet this guy, who turned out to be Tony Keating. It never occurred to me he wouldn’t want me in the band. To me it was a case of, ‘I’m going to this audition – who cares about anything else – I know I’m in.’”

Talking about the band she says, “I guess we were kind of in the moment. There was no precedent as far as we knew. I’d like to say we had a clear vision and we knew exactly where we were heading but we didn’t. We kind of just braved it alone, tackling whatever the next big challenge was. All I can say is that we would attack each and every problem with gusto. We needed a van to go touring. We really wanted to go! But we had no way of getting our instruments around. Providence always interferes though. My mum gave me a big chunk of money to pay for some driving lessons but I used it to buy us our band van, much to her annoyance! It was almost ruthless, we just did whatever we needed to.”

Talking about the punk scene she says: “It’s easy to explain what my vision of punk rock was now, because it’s been and gone, but at the time it was so new. We didn’t really know what it stood for, we just knew what we didn’t want.” Whilst Hines was just living in the moment with Keating, the two unknowing were a part of something much bigger than they had imagined.

She says: “I first saw The Stranglers at the Roundhouse. That venue was a smelly old place. They used to put straw on the floor because it would get so greasy and full of spilt beer! I think this was in 1977 when they were bottom of the bill to Kilburn and the High Roads which was Ian Dury’s band before The Blockheads. I loved the Stranglers because they did punk rock in a melodic way, they really appealed to me and of course Jean-Jacques Burnel was super easy on the eye.”

Being a woman of colour in a predominantly white based subculture, it is incredibly hard to imagine there was much representation to be found. She is unequivocal: “No, absolutely not.” She says there simply were no direct role models for her, and adds: “When I went to school I was the only black kid there. Our family moved to Surrey at a time when black people were supposed to stay in Brixton or Tottenham. We were the only black family around, not for long, but long enough for me to get used to the loneliness.”

From such an early age Hines was taught to remember the colour of her skin would ultimately play a large part in determining her future not only as an artist but an individual. “I was four when we moved to Mitcham and Mitcham was still a place of bank managers, building site managers, and head teachers.” This didn’t apply to her relationship with Tony, who is white, however: “My colour or my sex was no big deal for him as he comes from an Irish background and lived in an area that was very racially mixed. He grew up in Kentish Town and went to Acland Burghley School which produced a load of madness… including Madness the band. In those days Kentish Town wasn’t posh at all, everyone was ducking and diving, wheeling and dealing. And so Tony didn’t care. Back then his dad would hang around with a lot of Jamaican men, and Irish guys. I would always and still describe Tony as a brother from another mother.”

Hines demanded piano and ballet lessons from her parents at the age of four, so it’s fair to say that she knew exactly what she wanted from a very early age. Later she took guitar and recorder lessons, although she didn’t always care for writing her own songs, acknowledging that she preferred to collaborate with other people. She says: “We worked with Kirk Brandon back then. He was in a band called Theatre of Hate and then they changed their name to Spear of Destiny. They were one of the really big bands at the time. He was actually my ex fiancé. We had quite a mad life because he would be on Top Of The Pops and Radio One. He would be touring and in high demand but he still produced a couple of our tracks.”

She went from being a teenage girl with pop aspirations to becoming a singer, working in studios and producing her own music quite rapidly. Touching upon the incredible pace of her experience with Bona Rays, she says, “I remember, going from auditioning and joining the band, to actually rehearsing the songs was only about a two week period. It was a really short process, but totally by accident rather than by design. I wrote some lyrics, made the arrangements whilst Tony worked on the tunes. We went and recorded those two songs, a drummer auditioned and played on the recording that same day; we were really winging it!”

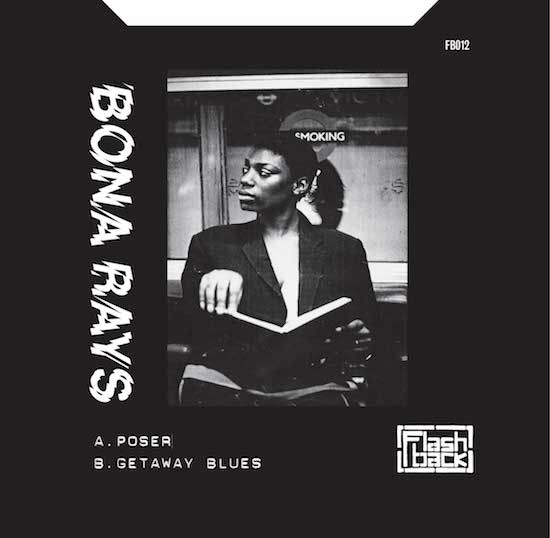

The tracks ‘Poser’ and ‘Getaway Blues’ were recorded in Highbury in 1978 by Chas and Tony with session drums and keyboards. The tracks were never released. Only one acetate exists which was cut a little while later. They punted it around record labels in 1978, but failed to get signed. Tony retained the master tapes, but up until recently only one copy of the single existed.

After you hear these two tracks, it’s hard not to wonder if there were any lost singles that hadn’t made it onto acetate. She pays tribute to Tony’s organisational skills, “He is amazing. He kept an archive of everything. I was very focused on writing and arranging songs, so Tony tended to be the person who kept archives of everything, because if it had been left to me they would have been lost. We recorded about ten songs in total.”

Looking back now, it’s as if you can hear the influences of X-Ray Spex and Lene Lovich in Bona Rays – but Hines wasn’t aware of them at the time. Since forming in 1978 a few people might say Hines and Keating were challenging punk at the right time. This is something that she has something to say about: “A lot of journalists have compared us to X-Ray Spex but we were coming out at pretty much the same time and I didn’t really hear them until a few years later.” [Ed: X-Ray Spex formed in 1976, had their first single out at the end of 1977, and their debut album in 1978.]

Despite the hard work however, the ‘Getaway Blues’ and ‘Poser’ single came to nothing. They opened for Hanoi Rocks, who were playing their first ever UK gig at the Fulham Greyhound; they cut the ‘We’re Never Going To Miss You’ single on their own Mystery label; and they changed their name to Violent Marriage – all in 1981. A couple of years later, after a line up change, they changed their name, again, to Our Heroes, and released a 12” single. They gigged for a couple of years after that and then split in 1985.

Three and a half decades passed with Chas and Tony still in intermittent contact but their luck was about to change: “I like to tell the story a step before walking into the store just because it’s slightly magical. I was packing to leave my flat and was in despair because there was so much to do. It was literally driving me insane. The removal guys were meant to be coming the next day and I wasn’t anywhere near ready. So in a fit of frustration I pulled out some boxes of records and thought, ‘Why the hell am I carrying around these old records?’ I called up a friend, he came round and we drove all the records down Essex Road to Flashback Records, which was the nearest place I could sell them."

She continues, “I left them with the owner Mark Burgess, went to grab a coffee, and then went back to get the money for them. At that point I noticed they also sold CDs and DVDs so I told him I had a few I’d like to sell. He said, ‘Yeah that’s fine, you wont get much money for them but I’m happy to buy them.’

"I went home and continued packing but I had this voice telling me to go straight back to the record shop and take my CDs and DVDs with me. I had to move boxes out of the way because they were so buried, as I hadn’t intended on getting to them anytime soon. I put them in a trolley went on the bus, and back to the shop. When I got back to Flashback, they were playing Bona Rays! The acetate of ‘Poser’ and ‘Getaway Blues’ had been in the pile of records I’d taken in to sell.

"People were bobbing their heads, the staff behind the counter were dancing around. I said to Mark, ‘Oh my God, I cant believe you’re playing this!’ Mark said, ‘Do you know who it is – it’s brilliant!’ I told him it was me and he asked me if I regretted selling it, but I reassured him I hadn’t listened to it in over 20 years. He then told me he would rip it and send me an mp3 version of it, which he did in due time alongside a long email saying he had played it to various people in the know and that he’d like to release it through Flashback Records. I told him I’d have to speak with Tony, to which he agreed and so that all began in September 2018.”

Chas recalls her experience once signing to Flashback records, “it was really quite a slow process, but it felt right not to rush it.” She continues, “Mark Burgess was really good, I have to say he could have done one of three things. He could’ve taken it all himself and not told us a thing about it, he could have brought us on board but say, ‘Actually I’m keeping all the money for this’, or the third thing, which is what he did, which was to build into the contract that we all get paid any money that comes out of this record as and when it comes up.”

This late career development and acknowledgment the duo have received have seemingly made their years of being undiscovered somewhat more bearable. Patience like this isn’t necessarily easily, and Chas takes a couple of moments before saying, “I don’t think I would change anything about the history of the group, because we made the record 100% authentic – it was true to ourselves. The rediscovery of the record has attracted people who have been completely authentic in their part too. Authenticity is very much part my makeup – I’m a black woman in a very white world, and not only in a white world, but in a world where even my own black men would want to put me down. I’ve had a real struggle to be an authentic, fully-faceted person and that is not something I will give up easily.”

With no remorse for the way things turned out, Chas turns to what she hopes for in the future of Bona Rays, “We’ve talked very deliberately over something we’ve often skirted around – putting the band back together. There’s been a few opportunities for us to play live. What we have now that we didn’t have back then is social media. There’s talk of things… but until we follow up on it, it’ll all dwindle away; now is the time to push it.”

2020 has the potential to finally give Bona Rays the admission they deserve and spotlight a potential autobiography from Chas Hines. “My mum told me how to read and write and do simple arithmetic by the time I was two because she had the idea in mind that I was a black child, so I needed to do things 100% better than everyone else. Writing a book is definitely on my agenda, with the working title of This Black Girls’ Life.”