Perhaps more than any other artform, music has the capacity to render language barriers irrelevant. Instruments, traditions and tunings may differ, as will the sociopolitical circumstances underlying any given artist’s work, but what’s often so striking about encountering music from distant regions of the world is how emotion, poetry and a desire to communicate cut right through its otherwise unfamiliar structures and syntax.

The vibrant, raw, strange yet enchanting music gathered on Mountains Of Tongues: Musical Dialects Of The Caucasus, a new compilation released through A Hawk & A Hacksaw’s L.M. Dupli-cation label, attests beautifully to that fact. Its songs and instrumentals, recorded across 2012 and 2013 during trips across Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, are sung in all manner of languages and draw from many different musical traditions – several of which have never been recorded before – yet they’re united by their powerfully expressive nature. Many are recorded in the field; with the ambience of the surrounding environment and the chatter of people left in, the results are grounded and evocative of their real-world locations, of living musical traditions persisting far beyond the attention of the wider world. Given their origins in a region of the globe that’s long struggled with inter-ethnic conflicts and political instability, the universally affecting humanity of these recordings, and their presentation as a single unified collection, feels potent.

The recordings were made by the Sayat Nova Project, a non-profit initiative set up by Ben Wheeler, Stefan Williamson-Fa and Anna Harbaugh while living in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi, as a means of documenting the region’s uniquely heterogeneous musical landscape. The Caucasus – the where Russia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe meet, and which encompasses Russian Federation territories such as Chechnya and Dagestan as well as Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia in the south – is an extraordinarily rich region in many senses. It’s a hotspot for biodiversity, with a high species richness of indigenous wildlife across a varied geographical landscape. But it’s also known for its unusually high cultural diversity, with a huge concentration of different languages, folk cultures and traditions across a relatively small area.

The Sayat Nova Project – named after the iconic 18th century ‘bard of the Caucasus’ whose compositions spanned multiple languages – was founded with the intention of creating an archive of recordings of the region’s lesser-known musical traditions. Mountains Of Tongues, released at the tail end of last year, collects a series of recordings made from their trips across the South Cacuasus – in-depth documentation of which is available at Wheeler’s blog, Caucascapades. However, explains Williamson-Fa, that’s only the start of the story. The Sayat Nova Project will eventually encompass a detailed online archive with multiple contributors, further releases are planned, and the duo will soon be extending their travels through the North Caucasus.

With the Mountains Of Tongues launch gig taking place at Cafe Oto this Friday, the Quietus met up with Williamson-Fa in London to discuss the project’s work to date and the lure of this unique area of the world.

I’ve been reading the blog covering some of your trips into the field with the Sayat Nova Project that led up to the Mountains Of Tongues compilation. Could you tell me a bit about the background of the Sayat Nova Project – what was the initial impetus to start it?

Stefan Williamson-Fa: I don’t know where the best place to start is! Both Ben [Wheeler] and I have been interested in the region for a long time. I first became obsessed with the Caucasus when I was about 15 or something. I’m from Gibraltar, and I was sitting on the internet one day and I came across Sergei Parajanov’s Colour Of Pomegranates, and watched it, and I was like, wow, amazing colours and sounds. I became obsessed with Parajanov, and him being [ethnically] Armenian but from Tbilisi in Georgia, and having made films in Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan – that kind of drew me in. That was my first exposure to the region, and then over the years I just listened to all the music that was available to me, watching films and reading histories and stuff.

Then in 2012 I decided I just needed to go, and I went and got a job as a teacher, but my idea was always to record music and to focus on music whilst I was there. And Ben, similarly, had been interested in the Caucasus for a while, and also was a teacher. I was obsessed with this type of Azerbaijani electric guitar playing I’d seen loads of videos of on YouTube, and one day I came across a short blog post Ben had written about this Azeri electric guitarist. So I contacted him and we started talking about doing some recordings. We had a few contacts in this ethnic Azeri region of Georgia, so we called up this guy we knew and we asked him if he knew any Ashigs, these Azeri bards who play the saz – there’s two tracks on the album [Ashig Gumbat’s ‘Aran Gedamamasi’ and Ashig Garib’s ‘Orta Saritel’.]

Feature continues below image

Ah yes, I’ve seen the videos you posted from those recordings.

SWF: That was the first recording session. Before that I’d listened to lots of Ashig music, but all the recordings I’d listened to were from Azeri Ashigs in Azerbaijan. So after that experience – just speaking to these musicians, finding out about this unique tradition of Azeri musicians in Georgia who have a different instrumental style and vocal style, even though it sounds very similar to the Azerbaijani tradition there’s lots of idiosyncrasies – that led us to think more about the representation of music in the region. How, in world music, the way folk music or traditional music is presented in these countries is very much linked to nationalism or nations.

And it’s not just in the [Caucasus] region. Obviously in the post-Soviet period there’s lots of nation building and nationalism, and that’s affected everything that goes on there in many ways. But even outside [the region], if you go to any record shop, if they have a CD on anything to do with the Caucasus, it’ll be Georgian polyphony music, or Azerbaijani mugam, or Armenian duduk. That’s always the way the world music industry works, it’s always in terms of countries and fixed and bounded groups, and the more we engaged with musicians in the region, the more we realised that’s not the way it works. [That model] hardly works anywhere – it’s not like that most places in the world – but especially in that part of the world, which is so ethnically diverse and has a history of extreme multiculturalism and contact between people and religions and ethnic groups and languages. So that triggered us to try and think of ways of dealing with this music that didn’t just repeat these ideas.

Originally we were thinking about stuff like working with ethnic minorities in Georgia, but then we realised that even by focusing on minorities or ethnic groups as bounded groups as well, you’re still promoting that idea of distinct cultures. So obviously what we’ve done so far isn’t perfect, but the idea is to get to the point where we’re promoting discussion, and an idea of interaction as opposed to separation.

Is that why you chose Sayat Nova as the character to head up the project?

SWF: Yes, completely. He was one of these bardic musicians in the 18th century, and he was born in Tbilisi – the present day capital of Georgia – but he was ethnically Armenian, and he wrote his poems and songs in Azerbaijani, Persian, Georgian and various different languages. So the perfect symbol of this multicultural history. And even today, even in Tbilisi – well, now, after the conflict, after the break up of the Soviet Union it’s a very different situation – but within Georgia, especially within Tbilisi, you’ve still got people who speak five different languages, and Azerbaijanis who drink tea with Armenians in the tea houses but are speaking in Georgian. All the syncretism and mixing and symbiosis, or whatever you want to call it.

Had there been a big history of inter-ethnic conflict in the area before the Soviet Union – for example, back in the days of Sayat Nova, are you aware of how integrated these communities were then?

SWF: It depends on who you speak to, because obviously the people involved in the conflict like to think that there’s never been peace and there’s never been harmony between groups. There’s always been certain tensions, especially in territories that are contested, but you can safely say that the urban centres of the Caucasus have always tended to be multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and relatively harmonious. It’s different in rural areas, I don’t want to generalise too much. That’s more in the South Caucasus. The North, what kind of links [the North and the South] are the mountainous communities, and there there’s a long history of blood feud and raids and people killing each other. But at the same time, as well as that there’s this other side of it, where there’s been lots of contact between groups in the mountains. So that links Georgia and Azerbaijan in the South to the North.

So it’s an incredibly complex series of interactions.

SWF: Yeah. It’s probably impossible to sum up. There’s just been a book released by Cambridge University Press, it’s a history of the Caucasus [James Forsyth’s The Caucasus: A History], a thousand pages long, and I think that’s probably the most extensive account so far. But it’s still probably missing out a lot.

Have you encountered many musicians during your travels that are similar in that sense to what Sayat Nova was doing – who are fluent in lots of different languages and traditions?

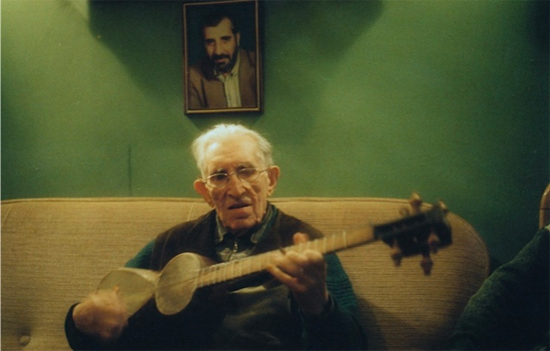

SWF: Yes. There’s loads of examples, but probably the most obvious one is that there’s this track on the LP by this guy called Sergo Kamalov, he’s a kamancheh player, a [type of] fiddle. Originally we had a longer track, we had to cut it down to fit it on the record, but the track was basically him playing an Armenian melody, then an Azeri melody, and then a Georgian melody. In the end we cut out the Georgian one because it didn’t fit, but still. This guy Sergo is 85 years old, ethnic Armenian, born in Tbilisi, speaks all the languages – Armenian, Georgian, Azerbaijani, Russian – and plays the music of all these cultures. Sergo was actually the leader of an ensemble called the Sayat Nova Ensemble in the 70s and 80s, but he’s just an amazing musician, he plays kamancheh, tar, drums, he sings – this incredible man living in a tiny apartment in this Soviet block in Tbilisi.

It must have been amazing as you started searching – finding these people along the way.

SWF: Yes. Some people we had contacts for, but others… A lot of the music we recorded is from musical traditions which haven’t necessarily been recorded before, and these are mostly the ones relating to ethnic minority groups. So in these cases we basically did a lot of research beforehand, trying to find contacts, and if not we’d just turn up and start speaking to people and asking about music and stuff, and eventually we’d be taken to perhaps the only musician in this town who knew how to play this strange instrument. There were a few occasions when that happened.

Because we were based in Georgia, we’d be recording stuff in the city [Tbilisi] all the time, and most weekends we’d go a different region or part of Georgia, and spend time there and record. That was ongoing. And then we did three trips to Armenia, mostly recording people in the capital, as it’s easiest, and then we had a long three week trip in Azerbaijan – which was not long enough! – which mostly focused on these ethnically diverse regions in the north, near the Georgian and Russian border. So we had to choose specific things that we thought were more important to find out more about – stuff that there was hardly any literature or recordings about – and focus on those. There’s lots of other musical traditions that haven’t been recorded and documented, so the aim of these recordings was just to fill in the gaps.

Sergo Kamalov playing mugam on the kamancheh

What breadth of recordings has historically been available of traditional music from the region? Have particular traditions of music from those areas been quite well recorded?

SWF: Yeah. In the North Caucasus there’s been hardly any, at least internationally distributed, recordings. There’s probably two or three albums in the last hundred years, or since recordings began! In the South Caucasus, in the republics, because of this national culture business, each country has claimed a tradition as its own and has promoted that. So in Georgia you’ve got polyphony, and in Azerbaijan mugam and this Ashig tradition, and in Armenia you have duduk, and each is part of [each country’s] UNESCO Intangible Heritage. So those particular traditions have been promoted a lot internationally, by the ministries of culture in those countries but also in the world music industry. So you have loads of recordings of Georgian polyphony, but not necessarily extensive [in a documentary sense]. Perhaps certain traditions are emphasised more than others. In Armenia you’ve got lots of recordings of big ensembles, and the same in Azerbaijan, at world music level and also Soviet-era recordings. The Soviets tried to promote specific cultures. You’d have these state ensembles and stuff.

What kind of challenges have you encountered in terms of the political instability of the region? I presume you had to be aware of where you could and couldn’t travel.

SWF: Yeah. For example in Georgia we never went to the breakaway regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It’s not that we’re taking sides and saying that their music isn’t important, we just didn’t have the chance, we didn’t have time. And we haven’t been to the North Caucasus yet. I’m hopefully going in June for a month or two, so we’ve been working with locals, exchanging information around setting up a North Caucasus part of the project. The whole idea of the project is to create a network. When the website is up, the whole purpose is for it to be a collaborative effort. I’m not the Sayat Nova project, Ben is not the Sayat Nova project – the Sayat Nova project is something that will exist outside [of us]. Essentially we want to be contributors to the project, even though we created it.

Ashig Garib – ‘Orta Saritel’

So is the idea to create an interactive map on the website with recordings linked to it?

SWF: That was the original idea, but then when starting to create the website, we realised, is a map the best way to represent what we’re doing here? Focusing on ethnic groups or traditions as belonging to a certain place – does that defeat the objective of the project? Are we reinforcing the idea of music belonging to a place or a group of people? That’s why the whole process of making the website is taking longer than we intended. So right now, what we’re going through is having the website as a place for people to submit and contribute essays, videos or photo stories or whatever. We want it to be as diverse and broad as possible, but making sure it fits the aims of the project. The most important part of that is getting people in these areas involved. We have a good friend and contact in the North Caucasus, in Kabardino-Balkaria, one of the republics within the Russian Federations. His name is Bulat Khalilov.

Do you know Vincent Moon, the film director? He started off doing the Takeaway Shows [on La Blogotheque] and then he lost interest in Western popular music and became a nomadic film-maker, as he calls himself – just traveling around the world making ethnographic, ethnomusical art films. He actually went to the North Caucasus in 2012, and made films all across the North Caucasus, [including] Dagestan and Chechnya, with Bulat Khalilov. Those are invaluable resources, no one else has recorded this stuff in such an unpolitical and beautiful way. Those films have now been released online. And this autumn he’s just been in the South Caucasus and set up a lot of recordings, and those films should be coming out soon as well. So together we’ve covered a lot of extra ground. He went absolutely everywhere.

Coming back to any problems we encountered, most people were very open, and most of the musicians had none of this political and ideological baggage that you’d expect. But other times we encountered this pure, just destructive nationalism.

Thinking of the recordings gathered on the LP, what sort of roles in society do these musics play? There’s so much variation in styles on there, I imagine there’s all sorts.

SWF: That’s the thing – in bringing out a release like this, how do you organise or compile these tracks? Do you do it by theme, or by instrumentation? There are infinite possibilities. But the tracks that actually made it were just based on general diversity and also hand picked through the subjective, aesthetic preference of ourselves and Jeremy [Barnes] and Heather [Trost, both of A Hawk & A Hacksaw]. So yeah, there was a huge diversity. Some of these musicians play in ensembles, like the Anchiskhati [Choir Trio], the one Georgian polyphony track with the yodeling [‘Adila-Ali Pasha’]. Those are three musicians from this church choir, but performing a folk style from their home region of Guria, this Western region where they have this vocal technique.

And even individual musicians have all these different levels and layers of performance. The third track is on accordion with this guy singing in Avar. Avars are an ethno-linguistic group mostly in Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan, but this musician – Absalden – was from the small Avar community in western Georgia near the border with Dagestan. He was the only musician in the village who knew how to play these folkier songs, but he’s also the only wedding musician in the town, so he has this massive Korg keyboard and he goes to Azerbaijan to play at weddings for people of the same ethnic group. So he played the agach komuz, it’s a very traditional Avar instrument which no-one else in the village knew how to play, and he could play all these incredible melodies. But then he brought out his Korg, set it up and was playing these pop wedding songs!

And also Sergo Kamalov, even though he also played all this traditional music, in the 80s he was in a rock band with his son, where everyone else was on electric instruments and he was on kamancheh. There’s a great photo of the band, all these young musicians with their electric guitars and basses, and then Sergo, this old man with his kamancheh. And once when we went over to his house he was playing us his old tapes, and on one of the tapes was this slightly sped-up version of Whitney Houston, ‘I Will Always Love You’. He was like "Ah, this is my favourite song of all time" – this man deeply connected to this traditional music, but his favourite song is Whitney Houston.

That’s something I was particularly interested in – the extent to which the traditional music still plays a role in day-to-day society. Wedding music, for example.

SWF: Most of the wedding music, though it’s based on traditional melodies and some songs, it’s mostly taken on new forms, and played on keyboards.

In a similar way as dabke is in the Middle East?

SWF: Yeah. But then you’ve got lots of interesting phenomena like Azerbaijan’s electric guitar tradition – people have taken on this electric guitar and started playing very distinct new styles of music influenced by mugam.

So there’s this interplay between the pop world and traditional music.

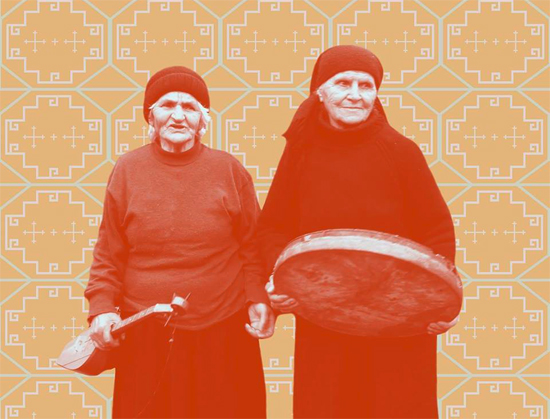

SWF: It happens a lot. People move between these worlds. They can sing the songs their grandmothers used to sing, and also get up onstage with an electric guitar and do completely new stuff. But most of the older musicians, the songs that they sang to us were very deeply connected to [older] associations. One of the last tracks is these two old women singing in Russian. They’re Molokan, it’s a Christian sect, and they were singing these prayer psalms. The recording starts off with an excerpt from a tape recording of their grandmother, who was 90 at the time, singing the same song. So in some cases these older musicians are still very much singing the same stuff.

I presume the Mountains Of Tongues compilation was put together from lots of recordings – how difficult was it to whittle down?

SWF: It was difficult, and then even more difficult cutting it down even more to fit the length of the LP. But then at the same time we’re planning other uses of it – everything will be available to hopefully everyone in the region and elsewhere, with the website. I’m going back to Georgia in July, I’m going to spend some time just saying hi to everyone, and we want to take the profits from the record back to the musicians on it. And also take the recordings back – lots of the people already have copies of the recordings now, and we’re going to leave them at various institutions and a lot of it will be online. Hopefully there’ll be a multi-tape compilation coming out soon. It’s just coming up with as many ways as possible [to distribute the recordings]. We’re hoping to do one of those reinterpretation compilations, where you get musicians to take inspiration from the music of the region – but we really want to get musicians from the region to contribute stuff as well, there’s a few really interesting bands who would fit in.

Both Ben and I come from strong DIY music backgrounds, and we want to make sure we’re using this DIY music ethic, but that we’re really engaging with the people from the region – not just going in and taking stuff out, but making something that lasts longer. That doesn’t mean we’re going to get it right, it’s a process of trying to get to a place where we’re interacting with this music in a different way, and creating new discussions that aren’t purely making a collection and then leaving and doing something else. But also thinking of new ways of engaging with this music. It’s interesting.

The compilation Mountains Of Tongues: Musical Dialects Of The Caucasus is out now via L.M Dupli-cation.

The London launch party for the compilation takes place at Cafe Oto, this Friday 17th January, and features The Family Elan, Maspindzeli and films from the Sayat Nova Project. Click here for more information and to buy tickets