Flashy nightclubs. Dirty little dives where you never see the light of day. Full of squares and creeps; the people on the make. For these are the places that women like to go to. You choose them or they choose you. Either way make sure the collar of your shirt isn’t greasy. Buy the girl a drink. Let her talk about herself. You can have a lot of fun. Don’t carry a lot around with you. When women dig you, you only need basics.

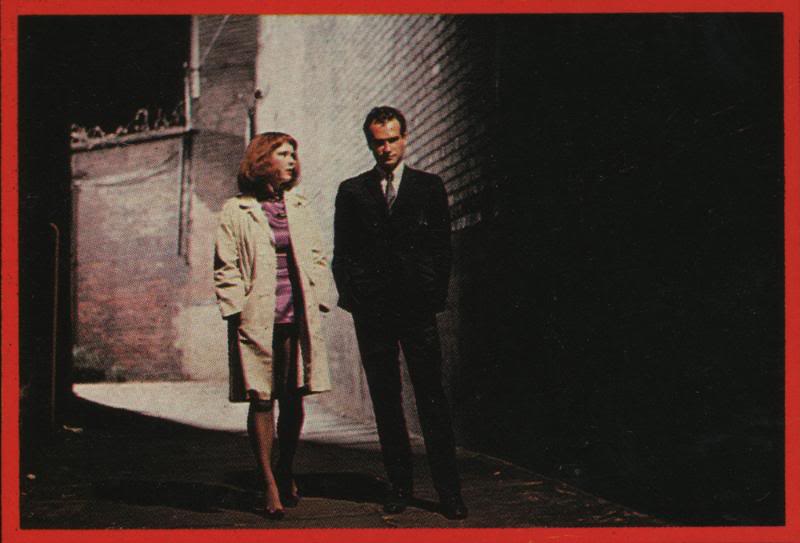

Johnny YesNo (Jack Elliot) steps out of the shadows – masculine in suit, cold-sweating under neon, bathed in deep vein crimson – a matinee idol in the underworld, sculptured features picked out by the harsh blue lights of A Punch Bowl Inn. This is Manchester, 1979, where the sun never rises. This is clubland as Hell on Earth. In doleful Yorkshire accent Johnny sets out the rules of engagement during a crepuscular taxi ride through flesh pots and night spots. Then he tells the story of two of his women, the sweet cocktail waitress Lorraine and the beautiful femme fatale and girl of his dreams, (Jude Calvert-Toulmin), not realising they are one and the same.

Of course dawn arrives as it always does bringing with it the light but this particular illumination comes too late for Johnny. He recognizes that he has been wrong to commodify women only after the knowledge can no longer help him. He ends up dumped, symbolically, in a gravel quarry, battered and bleeding. But is this really the end? After the credits, a miraculously fresh-faced and healed Johnny and an uninjured Lorraine drive off into the sunset together in an open top car. However this feels like the false endings that would be added on to other neo-noirs arriving later in the 1980s such as Brazil and Blade Runner. Despite being more ambiguous than either film, it still says (to this viewer at least), for those unable to cope with the violent physical and philosophical changes imposed by the pace of modern urban industrialized life, the only escape is often that into the imagination or insanity.

Johnny YesNo was co-written by feminist film maker Debbie Smith and Sheffield video artist Peter Care who also directed. It was shot in Manchester and the Pennines, with Care using Cabaret Voltaire music from the Mix Up and Voice Of America albums as a guide soundtrack. The disorientating, dubby, industrial, electronic music was such a perfect fit for the hallucinatory piece of celluloid however that he contacted the band to ask them if they wanted to contribute to the project and when they agreed out-takes from the film were re-edited with more Cabs music to form several short films to accompany the main feature. The entire project was self-released on VHS through the band’s Double Vision video label in 1982. This was the beginning of a very fruitful partnership that led to promo films for ‘Crackdown’, ‘Just Fascination’, ‘I Want You’, ‘Don’t Argue’ and ‘Hypnotize’. Perhaps most famously they collaborated on the ‘Sensoria’ video, which arguably represented the point at which industrial music crept out of the left field and into people’s homes via constant rotation on The Max Headroom Show, The Tube and the like.

Peter Care had taken a camera rig device designed and built by experimental film maker Tony Hill and used it to stunning effect in Johnny YesNo, fixing a camera to Jack Elliot as he slid down the loose face of a gravel quarry, always keeping the actor’s face at the dead centre of the screen. He took this and another Hill rig – the so called up and over – and used it to shoot the band and the character of a blind preacher and his daughter (archetypes probably culled from the American gothic of the Flannery O’Connor novel Wiseblood which was in turn made into an iconic film by John Huston) in urban and industrial decay. It caught the angst of the age perfectly. The viewer was near the end of the World In Itself (the Cold War) peering at the unfathomable idea of the World Without Us (a symbolic post apocalyptic landscape) in the same way that David Lynch’s Eraserhead had done in 1977. (Johnny YesNo shares many Lynchian preoccupations such as the illusory nature of selfhood and memory, seen in films such as Lost Highway and Mullholland Drive.) Care used yet another of Hill’s rigs to great effect on Depeche Mode’s ‘Shake The Disease’ video and it was this kind of work that saw him move to America where he became a much in demand promo director.

Peter Care and Richard H Kirk got back in touch with each other a few years ago and started work on Johnny YesNo Redux a new version of the film shot in LA, complete with extra shorts and a totally remixed soundtrack. I caught up with both of them to discuss the extensive project.

How did you get back in touch?

Richard H Kirk: The people who were looking after my website told me that Peter’s wife and producer Lorraine had been trying to get in touch. We’d lost touch in the early 90s and the last time we’d worked together was in 1989, filming the Cabaret Voltaire video for ‘Hypnotize’ out in Chicago. We got talking and said it would be great to put the original film out on DVD and then of course usually when you do this kind of thing people want extras or the company want extras to augment the original stuff. We just thought that it would be great to remix some of the music and remake some of the films. It was that simple really. I got in touch with Mute and they got together some money for us to go and do it really. It’s been made on a really tiny budget. I went away and started remixing the music in about 2005 and I finished it by March 2006 and sent all the music out to Peter in Los Angeles who then started on the re-shoots. He had two new actors lined up to play the main roles.

What kind of state were the audio and visual components of the original film in? Did they need much restoration?

RHK: Some of it did. Peter had an original celluloid copy of the film which was transferred to digital but as you can see it’s got scratches on it. There wasn’t much of a conscious effort to clean it up because it wasn’t too bad really.

Peter Care: I had two prints made of Johnny YesNo when I made it in 1979. One I gave to a little distribution company in London and I don’t know what happened to it, it just disappeared. So I had this one print that had the scratches on but I decided to leave it when I got it mastered and this was way before I knew I was going to be releasing it again with Richard. I had it mastered onto digital tape here in Los Angeles. I just decided to leave it the way it was. The frustrating part of putting the film together was in the audio quality. When you go from the source of the music, Cabaret Voltaire were giving me their master tapes and that was transferred to 16mm magnetic tapes and eventually that becomes the optical soundtrack on a 16mm print. The sound quality was really quite appalling. It gets rid of the top and the bottom of the frequencies, so leaving that optical print the way it was, was just a necessity but I wish I could have been able to remaster the soundtrack. There was just no way I was able to get all the individual elements after over 30 years though. In terms of the other pieces, I had one of the original half inch VHS compilation tapes and I used that as a master. Ironically the quality of the music on the half inch video was far superior to the sound on the film.

I do really like the scratchy, grimey feel of it though.

RHK: You’d could spend a lot of money on computer programmes to replicate the effect of those scratches on the film. [laughs] But this is the real deal.

There’s a real serendipity to how current it looks at the moment. I really like the fucked-up-ness of the first film. What I also think is interesting is that both of them conjure up the feeling of amateur pornography. Both forms are redolent of how cheap porn is and was made.

RHK: I must say a mate did say the new film reminded him of a Korean soft porn site, so yeah…

PC: When I shot the new footage three years ago the standard definition video camera which was pretty cheap and the HD camera had both just come out. You could buy them both very cheap. I knew I was going to be shooting hours and hours of footage. I knew there was going to be no way of storing the HD material on the hard drives of a team of editors working for free. It would have just gummed up the hard drives of the computers in the places where they were working for their day jobs. So using standard definition was more about the editing of it rather than the look of it although I did enjoy the freedom it allows you to have. We could shoot a 20-minute take on one camera. I like the look of it though. The almost too easy look of the video. Also the camera I bought was designed to take a really wide angled lens which was a really important factor.

How much of the new music is remixes? Obviously I recognize certain songs like ‘Yashar’…

RHK: Everything that was remixed was all stuff that was on the original Double Vision VHS release, so that’s JohnnyYesNo and there’s some other versions and some other little clips set to Cabs music. Originally before we started to work with him Peter had used some of our material like ‘Premonition’ and ‘News From Nowhere’ on the film.

’Partially Submerged’ is on there.

RHK: Yeah, and that’s from Voice Of America. So basically that’s why you find that material being remixed. I didn’t want to work on just JohnnyYesNo material but to do the associated stuff as well. I thought that was a more interesting idea. Everything on the new soundtrack and the CDs, it’s all Cabs material, I’ve just reworked it. [laughs] Which I know is going to piss off some people but it’s music that I wrote so I don’t feel bad about doing it really.

Well, they don’t really sound the same which is important. Usually when you think of a remix project you think of a piece of music that’s the same but with a donk on it or music that’s the same but with a fat dubstep bassline. This music is its own thing.

RHK: [laughs] This has just reminded me. On Friday I was DJing. There was a party in these flats in Sheffield which are being redeveloped and the bottom floor was turned into this warehouse party. But the funny thing was that we were in this Ballardian, high rise space and when I put the track ‘Premonition’ on – which has this dystopian, spoken word intro and all the security guards ran into the hall. And I was thinking, “Fucking hell man, I’ve hit the spot!”

When you used to play out live were you often hoping to provoke a response of anger or fear rather than necessarily one of enjoyment?

RHK: Probably a mixture of everything. I always used to say that early Cabs gigs were like a bad acid trip with the visuals and stuff. We were trying to totally immerse people into the sound and the visuals so people got lost in it. But that was more in the earlier days really, by the late 70s I think people liked what we did. Well, no one threw anything at us anymore. I don’t know whether that’s a good or bad thing. You know, the first concert we ever did in 1975 ended in a mini-riot and we had a few other things go off but nothing too major. But certainly in the early days there was a notion of confrontation, quite simply because what we were doing back then you just didn’t hear stuff like that so it was going to freak people out anyway just because we were different to the blander, popular music that was around at the time. I think when people were confronted by Cabaret Voltaire in the mid-1970s, then it was bound to upset a few of them, and as far as we were concerned that was a good thing.

It feels like Sheffield became a centre for multi-media self-sufficiency during the 1980s whether we’re talking the British Electric Foundation; or Chakk becoming Fonn Studios which in turn became WARP; or Cabaret Voltaire becoming a multi-media entity when such a thing was a weird thing for a band to do. How did you end up exploring all these different avenues? How did you go from being a band to having a video label

RHK: Quite easily. Towards the late 1970s we invested in some domestic video equipment; two video machines and a camera. I’d already been shooting loads of stuff on Super-8 that were projected at the live shows. And we just started to cobble together very crude videos, which culminated in the Double Vision Presents Cabaret Voltaire which we released in 1983 around the same time as JohnnyYesNo and was done on domestic equipment. But one of the things that was influential was I remember Public Image Ltd saying they were going to become a communications company and I was actually quite taken with the idea. I mean they actually didn’t do it but we did. We followed the idea through and along with Paul Smith from Blast First we formed Double Vision to put out underground video and at that time there was no censorship. You could release a video and you didn’t have to have a certificate and we thought this was a nice little loophole meaning we could release weird, arty films. And that’s really what we did. I think Stevo from Some Bizarre loaned us five grand because we were just starting to work with him, which we used to buy some video duplication equipment which was installed in Paul Smith’s house in Nottingham. It was a cottage industry initially. Paul would be running off all these cassettes that we would be selling mail order or through shops. And then Factory got their Icon thing going and we got to be mates with them. In fact I think some of our stuff was edited in Tony Wilson’s basement because he had an editing suite. Then they came in and took on the distribution and it just went from there. We decided to start putting out records as well, thinking that this would finance the making of more videos which would compliment the video releases. We did the film of JohnnyYesNo and then put out the album on vinyl. So there was no real mystery about it, Cabaret Voltaire had always been as much influenced by cinema as they were by music so we were always out at the local art house checking out Fellini or Bunuel or Warhol. And to me it was almost like a logical extension.

Was it your intention to make music that was as psychedelic or narcotic? Certainly the combination of the film and music is very hypnotic and druggy.

RHK: Totally. When we were working with it we had a rough diagram pinned to the wall of the studio where all the bits of the film were blocked out, and one of the bits was called the ‘Hallucination Sequence’ so you’re going to try and dive into that cold turkey… trippy kind of thing to compliment what Peter had going up on screen.

Where did the germ for Johnny YesNo come from?

Peter Care: At the time I had a writing partner Debbie Smith and she was part of the Sheffield feminist performance art scene and she was at the art school. And we were talking about how a lot of women were trying to put forward feminist ideas and I said to her, ‘Why don’t you it the other way? Why don’t you show what men are affected by and limited by in life? Why don’t you look at those politics instead of preaching to the converted?’ And from this idea I didn’t know how to take the film forward. I knew I didn’t want to make a political film, you know, the requisite 20-minute short for Channel 4 or the BFI, like many other directors were doing. I wanted to do something very different from the typical. So I started putting everything into a pulpish, film noir convention and I felt very at home with that because it was the sort of film I liked watching anyway. I had very eclectic tastes so one day I could be happily watching a Ken Loach film and loving it and then the next day I could be watching a black and white film noir b movie from the 50s and loving that just as much. So the idea was to put those two things into one piece.

Did you have a full script before you started making it?

PC: The people that financed the film the YAA (The Yorkshire Arts Association), they were the people who put up the money. So I sent the pitch and the script to them. That was in 79. I shot the film and when I was putting the film together, I’d already seen Cabaret Voltaire play live. I had copies of Mix Up and The Voice Of America. And I was using Voice of America as a scratch track. I was editing in their music over my images and the synchronicity was amazing. So I said to them would they be interested in doing an original sound track. I said I could use the The Voice Of America tracks but that it would be a lot more interesting if they produced a whole new soundtrack, which is what they did. That was in 79. In 82/83 Double Vision brought out the compilation and at that point I’d turned my back on the film making scene in Sheffield and the little film making company that I’d helped start and so on. I was a lot more interested in hanging out with bands like the Cabs. So I was working for them just for free, helping out wherever I could. If they ever needed a video compilation mastering, I knew how to operate the video machine. If they needed someone to project their films during a gig I would do that. By 82/83 I was on the fringes of what they were doing.

The film seems to successfully predict a big thing in mainstream 1980s film making which is neo noir whether we’re talking Bladerunner or to a lesser extent Angel Heart. What was it about noir that appealed to you at that time?

PC: I think on a thematic level it was very simple stuff. It ws a lot about people being trapped; people being paranoid. Men being victimized by events. It was the opposite to the romanticized story telling you get in most films. I also liked the fact that it was film language as much as the story itself that was developing the narrative. A lot of the European craftsmen that came across to America to make those movies, the cameramen, composers, directors, writers; they used their low budgets extremely well and I connected with that. That you could tell a really gripping story with a tiny amount of sets being built and locations and days for shooting. That fascinated me as a film maker. And also as a fan of American film making it clicked with me. The psychology of the films. The characters were drawn from very simple psychological archetypes. Especially the female characters. They were either the femme fatale or the bored suburban housewives left at home. You had to find a way of working round these archetypes.

The iconic scene in the quarry; was this the first time you’d tried out that method of filming where the camera stays attached to the actor so no matter what happens their face always stays centre screen?

PC: Yeah, that was the first time. I think it was the first time it had ever been done but here’s the thing, it’s a dangerous thing for a director to go, ‘Yeah, it was the first time it was ever done.’ I don’t know if you’ve seen it done earlier?

Not me.

PC: It just came to me as something to do and it was extremely difficult to get the whole rig to be practicable for the shot. The person who helped me was a guy called Tony Hill who was an experimental film maker who was very good at making camera rigs. I used one of his rigs in Sensoria; that up and over shot. That wasn’t my idea, that was Tony’s idea, I just put it in the context of a Cabaret Voltaire video. The thing with strapping the camera to the main actor Jack Elliot… well I hadn’t seen anything like it before. To be fair to Jack as well, although he could be difficult at times, he was incredibly heroic and courageous during that scene because he was upside down in a shale quarry and he could have slipped at any time and he had the BL camera, a 16 mm camera which is pretty heavy attached to a very big metal rig which was heavy itself. He didn’t complain and it was very strenuous and dangerous for him. I like the opening of that shot where he’s just breathing and the camera’s just breathing with him.

The quarry scene reminds me of a bit of the end sequence from Get Carter and the opening reminds me a bit of Taxi Driver, in as much as it’s this hellish vision of a city always in darkness just lit by sleazy neon lighting. What kind of films were an influence on Johnny YesNo?

PC: You’ve brought up something I haven’t thought about for a long time. Those two films did have a big impact on me subconsciously I think. At the time I was thinking more of Room At The Top where you had Joe Lampton played by Laurence Harvey sleeping his way into society. Also there was that Hammer film starring Stanley Baker called Hell Is A City which showed Manchester as this very seedy, criminal kind of place. You know… English crime… petty crime. But with a touch of glamour as well. The idea of a woman who has two identities, one disguised within another comes from Vertigo. But looking back, Taxi Driver and Get Carter are important films. They exist outside of genre. They are a lot more important and magnificent than the films I’ve just quoted you. The end of Get Carter for example. You can’t beat the ending; the slag of society is being tipped into the sea and that’s where he ends up. You can’t get much more symbolic than that. I think the idea of someone being drugged and then thrown into a quarry is a similar kind of idea, you’re junk, you’re worthless.

Johnny YesNo Redux, which contains two DVDs and two CDs is out via Mute on Monday November 14