Just before Xmas in 2008 The Quietus received a promo that caused a bit of a stir in the office. The CD – which arrived with no press release, no covering letter and no sender information – was a tough collection of acid electro remixes of a New Zealand Maori dub outfit called Kora on Shiva. No disrespect to the blunted Antipodeans but our brains were scrambled and our pulses sent racing because of the name of the remix outfit: Cabaret Voltaire.

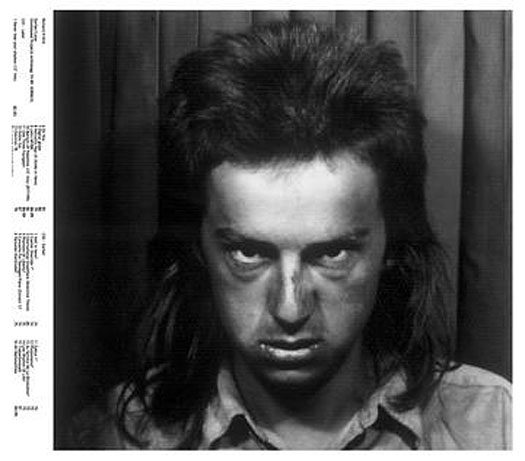

Was this the Cabaret Voltaire… who, along with Throbbing Gristle and Public Image Limited, were embarrassingly ahead of the field, during the post punk years – a time when groundbreaking bands were seemingly ten a penny? The Sheffield based avant gardists who moved from Dada-influenced tape loop/ home-made electronics through proto-industrial, post punk, EBM, electro, acid, machine funk, proto-house, ethno-techno and beyond until splitting up in 1994? The original trio of bloody-minded sods (Chris Watson, Richard H Kirk, Stephen Malinder) who released the still scabrous sounding treated guitar/electro punk racket of ‘Nag, Nag, Nag’ and decimated dub of ‘Sluggin’ Fer Jesus’? The slimmed down but no less oppressive and inventive duo (Kirk, Malinder) who released the singles ‘Sensoria’, ‘Crackdown’, ‘Thank You America’, ‘Yashar’ and ‘Here To Go’?

A year later when the Cabs’ name popped-up attached to another remix project on Shiva (National Service Rewind by The Tivoli), the answer it seemed was yes. By now, industrial message boards had cranked into over-time, coming up with all-sorts of theories. It seemed like Kirk alone was now using the Cabaret Voltaire name… as well as the immense amount of effort he’d already been throwing into Sandoz, Al Jabr, Biochemical Dread, Blacworld, Dark Magus, Destructive Impact, Dr. Xavier, Electronic Eye, Extended Family, Frightgod, Future Cop Movies, International Organisation, King Of Kings, Multiple Transmission, Nine Miles Dub, Outland Assassin, Papadoctrine, Port Au Prince, Reflexiv, The Revolutionary Army (Of The Infant Jesus)… well, you get the picture.

And why resurrect Cabaret Voltaire at all? Surely they were the last fucking band who should be dragged back for one last turn under the spotlights… The least nostalgic band there was.

[For some context, my review of the Kora remix album from December 19, 2008, read thus: “The only word from Kirk’s press bod is that they ‘have lined up select shows for 2009 – dates, content, format and locations tbc. It’s going to be a bit special, that’s guaranteed’. Well, I acted a bit ‘special’ on hearing this and nearly rendered the office to matchsticks with a cricket bat. Thinking ‘For fuck’s sake – if this is a Don’t Look Back rendition of Microphonies at Koko, I’m literally going to kill someone.’ There’s simply nothing wrong doing retro/ nostalgia shows if you’re a foot note in the history of indie like Teenage Fanclub or Stump but for the two decade career of one of the UK’s most forward-looking and uncompromising bands to be sullied like this would be an exercise in seizing ignominy out of the jaws of sublimity.”]

However, a recent lengthy chat with Richard H Kirk put my mind at ease. These are exciting times indeed for fans of the industrial and the futuristic. Not only do we have violent young bucks Factory Floor to contend with but now we have the Cabs back as well. And, just as it should be, they are refusing to revisit old glories and instead plan new work in the field of electronic music, installation, film and art.

Why did you choose to revive the Cabaret Voltaire name for the Kora! Kora! Kora! and The Tivoli remix projects?

Richard H Kirk: It was just a question of circumstances really. When you say ‘revive the name’ I don’t know what kind of rumours or theories are going around about that but just to make everything completely clear: there used to be three people in Cabaret Voltaire. One of them [Chris Watson] left in 1981 and the other one [Stephen Malinder] left in 1993 leaving me with the option to carry the project on, which is something that I have thought about quite a bit. But basically with Kora [New Zealand based dub unit], that came about because the person who puts out their records in Europe is an old friend of mine and at one time was involved in the management of CV. We became reacquainted in some sad circumstances. An old friend of ours passed away in 2007 and I hadn’t seen this guy Amrik [Rai, of Shiva Records] in about 17-years because we hadn’t parted on particularly good terms but I had the option of using the name which was agreed when Stephen left in 1993 but I never had it written down in legal terms and that’s the difference you know. That was resolved and that left me free to go forward with Cabaret Voltaire. But I wanted to form the band for now not to form a band to go out and rehash all those old songs, which is what seems to be very popular at the moment, as you’re probably aware. I wanted to totally avoid that. As far as I was concerned, Cabaret Voltaire was always about looking forward not looking back. The idea was to do something totally new and not be reliant on playing hits. Not that we ever had any hits of course! So that was the circumstance of the name coming back and then Shiva Records asked me to remix the Kora record. I’d seen them play live a couple of times and really enjoyed them. I liked what they were doing but thought maybe there’s an alternative way to present this. Make it a little bit darker. Bring out the dirtiness of it. It was a way of stepping back into it. Everyone seemed to like what I’d done with it. The Tivoli [Sheffield indie band] were on the same label and had the same management, I got on well with them so a similar thing happened. I tried to take apart what they’d done and put it back together in a slightly different fashion.

Like you’ve just hinted at now, there seems to be a lot of interest in early doors UK industrial. There are obviously pros and cons to this. What’s your take on a younger generation of people getting into the Cabaret Voltaire/Throbbing Gristle sound?

RHK: It sounds similar to me in the 1970s getting into the Velvet Underground. If people are bored with the present then they will look back for inspiration. It isn’t that different to what I did with Cabaret Voltaire. A lot of the stuff that inspired CV was stuff from Germany in the early 70s and stuff like the Velvets. To me it just seems like a similar sort of thing.

Have you been approached by ATP or one of these organisations to do a Don’t Look Back show for Microphonies or Crackdown or whatever?

RHK: No and I’d say no anyway. That’s the past and I can see no point of doing that other than money and that’s never been my main motivation over the past 30 odd years making music. It’s never been the be all and end all. I’d probably enjoy going along to see people doing that kind of thing from a personal point of view but it’s not something that I’d want to do at all. I mean I’d love to see the Stooges play again but sadly it’s never going to be the same is it? A lot of the circumstances change, the people change… I can’t see the benefit for us doing it.

It’s quite reassuring to hear that. In this day and age, it feels that every single band that has ever existed is going to reform in one way or the other. But if you’re not interested in that are you interested in creating new electronic music as Cabaret Voltaire?

RHK: Yes. In a word. Electronic music is a fairly broad-ranging term but the thing for me is to take Cabaret Voltaire out of rock venues and into maybe galleries and I’m still working on ideas for that and I’m not in a rush. It’s been 15-years since the last album and I’m not suddenly going to rush and cobble something together in a half-arsed manner. It’s a case of what I’d initially like to do is make it more like an art installation where it’s not really like a band playing on stage any more but maybe it’s a lot of visual material accompanied by a live soundtrack but with the focus perhaps not on people dancing around or having a front man or traditional kind of rock based performance. That’s what I see happening with it initially. That’s what I’m playing round with at the moment. When I’ve got something that I think is worthwhile and could break some new ground then I’ll do it. Otherwise you won’t be hearing it or seeing it. It’s not just something that can come together in an afternoon or whatever.

Are you seeing it as more of a solo thing for you under the Cabs name or will it eventually become more of a collaborative thing?

RHK: It may be that as it progresses it will involve other people. I mean I’ve already had a lot of people who have said that they’d be interested in getting involved but the initial thing won’t be like that. It really kind of annoys me when… I read something on the internet that said ‘Oh it’s just Richard Kirk using the name…’ It’s been my fucking life for the last 35-years. Just because other people have left the band [it doesn’t mean I have]. I find it a bit offensive that people would think that’s what I’m doing; that I’m simply taking the name for whatever reason. I feel more deeply about it than that and people shouldn’t really mouth off about it until they understand or know what the circumstances are. I was the person left to carry it on and as I said before, my motivations aren’t financial. If people want to try and say that that’s what it is, then unfortunately they’re barking up the wrong tree. I don’t need to do that. I do a lot of other music myself. It’s not like I’m doing it because I suddenly need to pay a tax bill or generate some cash because to me that would be repulsive because of the history of Cabaret Voltaire. It would be repulsive because it was never done for commercial reasons ever really. I think the best we ever did commercially was when the Crackdown album went in the top 40 in 1983. I don’t see it like that and I don’t care. I’d sooner just be judged on what it is that I do next as a Cabaret Voltaire project.

And there are probably easier ways to earn money than releasing a Cabaret Voltaire album…

RHK: Er, yes, I should imagine so… bank robberies, organized crime…

What’s happening with your Chris Carter collaboration?

RHK: I think the thing you’re referring to is a project that was suggested, funnily enough, by another guy who used to manage Cabaret Voltaire, Paul Smith from Blast First. Paul knows that I’m a very big fan of JG Ballard. Before he [JGB] died, sadly, last year, Paul sent me some photographs that a writer friend, Iain Sinclair had taken on these walks through London. He’d come through Shepperton and come past Ballard’s house there. Paul said ‘How do you fancy doing a project based on this?’ Ballard had actually written most of his work in this house. I came back and said that I would give it a try… try and write something that was loosely based around Ballard’s work without being too specific and the idea was it would be 12" with me doing one side and Chris Carter would do the other. That’s as far as I understand it anyhow. My piece unfortunately ended up being 40 minutes long however. Believe it or not, I didn’t have broadband at the time. I didn’t really use the internet apart from for the odd email and Chris got me a lot of Ballard’s spoken word stuff from You Tube and other sources. I wanted to use his voice in the piece and it became more like a soundscape than a techno track or whatever. It involves using Ballard’s voice, processing it and making it part of the soundscape. You’d have to ask Paul when it’s going to be released though. I’ve suggested that we put out a ten minute extract of mine with Chris’s track as well and I’d later release the full version on CD but I guess it’ll be whatever Paul decides. At the moment it isn’t titled. It’ll be under my own name rather than one of the many aliases that I’ve used over the years.

I’m quite curious about this… I’m by no means a Richard Kirk completist but I do know people who are and you have worked under a dizzying array of aliases. I was wondering how much method or madness was applied to assigning a particular name to a particular project?

RHK: Probably madness is the key word here! [laughs] I’ve used certain names – Sandoz is probably one of the more well known – that have a particular remit. It started off as a fusion of Western European electronic music and African and Latin music together. So that particular project was specific but a lot of the time I don’t even name a project until it’s done. Generally not anyway. It’ll be more like I just don’t want to put it out under my own name for various reasons… not because I don’t think it’s any good but for other reasons. It’s kind of interesting, kind of like writing a novel. You know, creating fictitious art. That started in the late 80s with our white label thing we had going on. It was quite liberating back then to put music out that wasn’t judged by 25-years of history. When I first did Sandoz, no one knew it was me and it was great but obviously you can’t maintain that level of secrecy for two decades though. I wouldn’t go as far as saying that it’s supposed to be humorous but there have always been some dark elements of humour to it. I like making names up, creating fictitious groups, if that makes any sense.

Recent events in Haiti must have dredged up pretty strong emotions for you…

RHK: Yeah… but I only ever went there once you know. I spent about a week there in 1991 but obviously looking at the TV footage I got to know a lot of those places that got trashed. I found my trip there to be invigorating but for a lot of the time I was also shit scared… There were people with guns everywhere and back then there was even less in the way of law and order. It was like going to somewhere during a moment of madness. I went there intending to shoot some footage and I didn’t really shoot that much. It would have been too conspicuous to carry round, what was then quite a large Super-8 camera. But something about that experience stuck with me. Many people say that travel is a great experience to broaden the mind and it is a great experience for artists and writers and musicians. I was very sad to see what happened there. I’d always kept tabs on what happened there and I think the Americans have a lot to answer for in the terms of blame. Obviously not for the earthquake itself… but in terms of [how bad] the economic situation is over there. They stopped people there from breeding a certain type of pig which they had been doing for years. Then they stopped them from growing a certain type of rice and the economy started to get dependent on imports instead of producing for itself. And yeah, it’s sad and it’s dropped out of the news altogether now hasn’t it? It’s been replaced by other things but the fact remains that up to 200,000 people were killed or are still missing as a result of that earthquake.

But when you went there, things were in a state of upheaval for different reasons weren’t they? When you went it was just before a military coup…

RHK: That’s right, yeah. I was there in August of 91 and there was a coup in September. That may have been the reason why it seemed so tense. I know people who have been there subsequently. Andy Kershaw the world music DJ, he went there. I think the lesson to be learned is: if you want to go to places that are a bit on the edge you really need to be in touch with someone local, who is going to look after you and make sure you don’t end up in the wrong place like down a back alley with your throat cut.

I guess it’s fairly well known about you that you’ve long been interested in blue collar dance music from around the world. Perhaps Jon Hassell would have called it Fourth World Music. Being a fan of things like this and afro-futurism, what do you make of the current revitalisation of the fortunes of afrobeat, hi-life and palm wine and genres like that?

RHK: What, you mean bands like Vampire Weekend? I’ve not really heard any of it to tell you the truth and that’s all I can say. I must say I’m slightly cynical though in some ways but then again I’m kind of like that anyway. But I must admit the first thing I thought was that I should start reissuing some of the music that I did in the early 90s! Because I read somewhere that ethno-techno was the new thing. I was thinking it was new in the early 90s…

Vampire Weekend are pretty unsatisfying I think but on the other hand there is a band called Foals who actually do something interesting with the building blocks. What do you make of reissue culture spreading to African music as well though? There are a lot of reissues coming out on Sound Way and Analog Africa that put out stuff like Nigerian psych rock, Soweto disco and Ghanaian hi life…

RHK: You took the words straight out of my mouth there because some of these reissues… There was a guy on 6Music playing some of this Nigerian reissue stuff and it sounds fantastic. Then there’s something else I missed out on at the time is being reissued now in the Ehtiopiques series. When I first heard that, I was like ‘Fuck me!’

I heard on a documentary recently, Martin Ware from BEF/Human League/Heaven 17 saying that people would go to parties round your place in Sheffield in the late 70s early 80s and you’d always be playing futuristic and ‘mindblowing’ dub. Do you still listen to dub and what do you make of modern strains such as dubstep?

RHK: Dubstep… How valid a term is that? Did the guys who make dubstep, invent that term? Is that what they call it? That’s what I’d be interested to know… In general terms, from what I’ve heard, some of that stuff sounds amazing. In general terms I went to Jamaica in 1998 and got re-energized back into that kind of music and ever since then I’ve been into dancehall. There was a period when there were some really good dancehall stations around Sheffield, getting dubplates cut and bringing them over. I’m finding it more difficult to find this type of music these days though. Radio 1 still has a dancehall program but whether that’s the really cutting edge stuff or not, I don’t know. When I was first getting into dancehall, I just thought that it was so much further advanced than the latest banging house or techno. I just thought the energy in there was full-on. I mean, obviously, I’m not that keen on the homophobic content in some of the music that you get but I’m still a fan of that whole genre. Jamaican music has been ahead of the game for a long, long time.

I was interviewing Nitzer Ebb recently and said there was one word that didn’t get mentioned in connection with their music enough, and that was “funk”. I think the same thing could be said even more so about you. And I’m fully aware that you released singles called ‘James Brown’ and ‘Big Funk’. I guess the outsider’s view of this, is that it’s deeply stiff music and not funky at all. But really I guess that you didn’t sound too much more weird and alien in 1982 than the J.B.s did in 1972.

RHK: Yeah, I mean I’d say that with Cabaret Voltaire as well as being really interested in leftfield electronic music, the kind of music that we grew up loving was black music. You wouldn’t call it that now but things like Motown and then later James Brown, George Clinton, [Hamilton] Bohannon, the Fatback Band. That was always there. I think the difference is that when we started in the 70s we weren’t really able to do that kind of stuff because quite simply we weren’t good enough musicians. But when the technology changed in the late70s to early 80s it became more within our grasp to do dance music in inverted comments.

Performing as Blacworld on ‘Subduing Demons In South Yorkshire’ you talk about your dad being a radio ham. I was just wondering to what extent you were carrying on a tradition started by him? Over the years you’ve used a lot of tapes or samples or loops of radio transmissions…

RHK: I don’t know whether that was a particularly conscious thing. My father was a steel worker but he always had hobbies and one of them was tinkering with radios and electronic stuff but he also did photography and painted a bit. Where we lived there was an attic with all his stuff in it. I inherited all this stuff. He had loads of those practical electronics and practical wireless magazines. One of the fuzzboxes that I used with Cabaret Voltaire in the early days came from one of those magazines. It came from an article to build your own fuzzbox. I gave the feature to Chris Watson and said can you make this? Chris was a telephone engineer and had expertise in that area as well. It’s not like something that I thought about consciously but you know, little bits and pieces of what my dad had, like his super 8 camera, I inherited when he died. That’s kind of where the Cabs visual side of things came from because I was making films on Standard 8 and stuff like that. Fucking those up and melting bits of film and scratching it and all sorts. I spent a bit of time at art school in Sheffield trying to develop that further. So you know, you’re not far off the mark… the radio thing has always fascinated me. I soon learned that when you’re trying to make crude electronic music and you don’t have much money and you don’t have very expensive synthesizers, you only have to look on short wave and you’ve got this fantastic pallet of sounds that’s floating around in the ether, you know? It became a sound source; a quick route to getting hardcore electronic sounds without having the added expense, generated by buying a synth. And the voices you’d hear on short wave… I guess it was like the internet is now. There were people all over the globe transmitting all sorts and that’s before you go into all the encrypted transmissions… The clandestine stuff… You got companies and security agencies sending data to one another but it’s encoded. And it sounds fantastic!

You talked before about fucking stuff up and burning bits of film and the chance element that probably creeps into the sound making process when you build your own equipment… Do you see this as something that’s missing in today’s locked-in world of what you can and can’t do as regards soft synths and computers?

RHK: To a certain extent, yeah. That kind of randomness and DIY element has been lost a little bit with computers. But what pisses me off with computers on one hand and is fantastic on the other is when you’re doing music on computers you’re never finished because you can always save that version and start doing other stuff with it. And maybe part of the talent these days lies in knowing when something is finished. Otherwise you could just go on and on and on.

You’ve mentioned Sheffield a lot and your name gets mentioned in connection with Sheffield’s musical history a lot so I was wondering about the city’s physical influence on your music. It’s approaching a cliché to say this but I was wondering to what extent the heavy industry of your home city had influenced your sound in the same way that bands like Judas Priest and Black Sabbath claim the drop forges and steel mills of Birmingham influenced the genesis of heavy metal?

RHK: You’ve been watching the Heavy Metal and Synth Britania series!

Yeah!

RHK: That was really weird you know. I saw those programs. Well, I was in one of them. It was kind of weird really because the people in the two different documentaries were saying nearly exactly the same thing…

But, the music couldn’t be more different could it?

RHK: I mean, I did actually live right on the edge of this area called Pitsmoor which has been made famous by mate Richard Hawley who also comes from Sheffield. I lived right next to this sprawl of industry in Sheffield. It is where my dad worked and you could hear it. But I also think it’s a little bit too easy to explain it away like that. It wasn’t a case of ‘Oh yeah, I can hear all these weird noises in the night coming from the forges…’ I don’t think it was then a case of ‘Well, I’d better go off and do some music that sounds like that.’ I don’t think we thought about it. The whole thing with industrial was that wasn’t a term that Cabaret Voltaire invented, the first people I heard of using that term were Throbbing Gristle and they called their label Industrial and their slogan was ‘Industrial Music For Industrial People’. And I think that kind of got stuck onto Cabaret Voltaire as well because we all came out at the same time. And it did become a bit of a cliché, you know. But you can’t deny the fact that back then Sheffield was kind of like the big steel, industrial city. Sadly a lot of it went. It was something that was always there and I was in very close proximity to it. A few minutes from where I lived. We used to go down there to play when we were kids and fantasize about what all these different buildings were. It was the end result of watching too much sci-fi, your imagination running riot, you like to think about what things could be… not what they were.

You mentioned Throbbing Gristle as contemporaries in the 1970s but did you feel a kinship with any of the indie or punk leaning groups who came after you – bands like The Fall, Joy Division or Public Image Limited?

RHK: I think Joy Division were the special case. We knew them quite well. I just watched Control a couple of nights ago and I was chuckling to myself watching it… well, obviously, it’s also a quite sad thing. Three or four of these people that I knew who are portrayed in that film, are now dead. But Joy Division definitely… At a certain point in time in the late 70s there were three important bands. One was Throbbing Gristle. Another was Cabaret Voltaire. And another was Joy Division. On one extreme you had Throbbing Gristle who were not musical and on the other side you had Joy Division… who were experimental but they were also rock and had recognizable song structures. And somewhere in the middle you had Cabaret Voltaire who were, in some ways, a bit of both. Initially I didn’t get The Fall but we played a live show up with them up in Newcastle and I got converted and I used to know Mark E Smith quite well. Both those bands came and recorded at Western Works and after Ian had died, what became New Order came and recorded some tracks there and maybe a year or two later The Fall recorded there as well. I think it was when they were still on Rough Trade. Public Image, some of their stuff I enjoyed. The Pop Group I liked, you know, Mark Stewart’s group.

Another big dub fan as well…

RHK: Yes, exactly.

What can you tell me about the Johnny YesNo film reissue?

RHK: Basically what’s happened is that I’d been out of touch with Peter Care who directed that film and quite a few of our more ‘well known’ promos. I lost touch with Pete because he moved to Los Angeles in 1985 and then in 2005 I got a message that he’d been trying to get in touch and we got back in touch. I said it would be great to reissue Johnny YesNo. The original film was put out on Cabaret Voltaire’s Double Vision label; the short film and load of even shorter clips running to about an hour which we originally went out on VHS. I said it would be nice to make that available on DVD because it’s not been available since the early 80s. I said we could go and talk to Mute, who issued quite a lot of Cabaret Voltaire’s back catalogue and archive stuff. And then said ‘What about if we make a new version of it? I’ll remix the music and you remix the pictures.’ We got the project together and basically I did my bit, remixed a selection of music which includes bits and pieces from Voice Of America as well as the Johnny YesNo soundtrack and just sent it to Peter and left it with him. He got a new actor and actress and kind of more or less re-shot the whole thing in LA in a contemporary context. It was finally finished last year. It’s been a long, long project this. I think it’s going to be released in May and there was a preview screening at the Sensoria Festival in Sheffield this week. So basically that’s it. The whole thing is going to be one DVD with Johnny Yes/No and associated material and a new DVD which is going to be about 2.25 hours long with the new version of the film and loads and loads of extras and two CDs as well with all the remixes.

The Quietus would like to thank Clive Harris for his help behind the scenes